Graham Clarke: How do we read a photograph? From 'The Photograph' 1997

|

Whenever we look at a photographic image we engage in a series of complex readings which relate as much to the expectations and assumptions that we bring to the image as to the photographic subject itself. Indeed, rather than the notion of looking, which suggests a passive act of recognition, we need to insist that we read a photograph, not as an image but as a text. That reading (any reading) involves a series of problematic, ambiguous, and often contradictory meanings and relationships between the reader and the image. The photograph achieves meaning through what has been called a 'photographic discourse': a language of codes which involves its own grammar and syntax. It is, in its own way, as complex and as rich as any written language and...involves its own conventions and histories. As Victor Burgin insists:

THE INTELLIGIBILITY OF THE PHOTOGRAPH IS NO SIMPLE THING; PHOTOGRAPHS ARE TEXTS INSCRIBED IN TERMS OF WHAT WE MAY CALL 'PHOTOGRAPHIC DISCOURSE', BUT THIS DISCOURSE, LIKE ANY OTHER, ENGAGES DISCOURSES BEYOND ITSELF, THE 'PHOTOGRAPHIC TEXT', LIKE ANY OTHER, IS THE SITE OF A COMPLEX INTERTEXTUALITY, AN OVERLAPPING SERIES OF PREVIOUS TEXTS 'TAKEN FOR GRANTED' AT A PARTICULAR CULTURAL AND HISTORICAL CONJUNCTURE. This is a central statement as to how we 'read' the photograph as a text and underlines the problematic nature of the photographic image as both arbiter of meaning and trace of the 'real'. And in a crucial way it lays clear the extent to which any photograph is part of a larger language of meaning which we bring to our experience of the photograph.

|

Much of Burgin's understanding of this discourse was, consciously at least, quite alien to 'readers' of the photograph in the nineteenth century, although we can claim with some confidence that much photography was 'read' in relation to the accepted language of painting and literature of the time, especially in terms of symbolism and narrative structure. Early commentators like Poe, as much as Hawthorne, Holmes, and Baudelaire, noted the literal rather than symbolic aspects of the photograph, ignoring the extent to which it replicated cultural meaning rather than actual things.

The photograph both mirrors and creates a discourse with the world, and is never, despite its often passive way with things, a neutral representation. Indeed, we might argue that at every level the photograph involves a saturated ideological context. Full of meanings, it is a dense text in which is written the terms of reference by which an ideology both constructs meaning and reflects that meaning as a stamp of power and authority. We need to read it as the site of a series of simultaneous complexities and ambiguities, in which is situated not so much a mirror of the world as our way with that world; what Diane Arbus called 'the endlessly seductive puzzle of sight'. The photographic image contains a 'photographic message' as part of a 'practice of signification' which reflects the codes, values, and beliefs of the culture as a whole. Its literalness, as such, reflects the representation of our way with the world the site (and sight) of a series of other codes and texts, of values and hierarchies which engage other discourses and other frames of reference; hence, its deceptive simplicity, its obtuse thereness. Far from being a 'mirror', the photograph is one of the most complex and most problematic forms of representation. Its ordinariness belies its ambivalence and implicit difficulty as a means of representation.

To read a photograph, then, is to enter into a series of relationships which are 'hidden', so to speak, by the illusory power of the image before our eyes. We need not only to see the image, but also to read it as the active play of a visual language. In this respect two aspects are basic. First, we must remember that the photograph is itself the product of a photographer. It is always the reflection of a specific point of view, be it aesthetic, polemical, political, or ideological. One never 'takes' a photograph in any passive sense. To 'take' is active. The photographer imposes, steals, recreates the scene/seen according to a cultural discourse. Secondly, however, the photograph encodes the terms of reference by which we shape and understand a three-dimensional world. It thus exists within a wider body of reference and relates to a series of wider histories, at once aesthetic, cultural, and social.

The photograph both mirrors and creates a discourse with the world, and is never, despite its often passive way with things, a neutral representation. Indeed, we might argue that at every level the photograph involves a saturated ideological context. Full of meanings, it is a dense text in which is written the terms of reference by which an ideology both constructs meaning and reflects that meaning as a stamp of power and authority. We need to read it as the site of a series of simultaneous complexities and ambiguities, in which is situated not so much a mirror of the world as our way with that world; what Diane Arbus called 'the endlessly seductive puzzle of sight'. The photographic image contains a 'photographic message' as part of a 'practice of signification' which reflects the codes, values, and beliefs of the culture as a whole. Its literalness, as such, reflects the representation of our way with the world the site (and sight) of a series of other codes and texts, of values and hierarchies which engage other discourses and other frames of reference; hence, its deceptive simplicity, its obtuse thereness. Far from being a 'mirror', the photograph is one of the most complex and most problematic forms of representation. Its ordinariness belies its ambivalence and implicit difficulty as a means of representation.

To read a photograph, then, is to enter into a series of relationships which are 'hidden', so to speak, by the illusory power of the image before our eyes. We need not only to see the image, but also to read it as the active play of a visual language. In this respect two aspects are basic. First, we must remember that the photograph is itself the product of a photographer. It is always the reflection of a specific point of view, be it aesthetic, polemical, political, or ideological. One never 'takes' a photograph in any passive sense. To 'take' is active. The photographer imposes, steals, recreates the scene/seen according to a cultural discourse. Secondly, however, the photograph encodes the terms of reference by which we shape and understand a three-dimensional world. It thus exists within a wider body of reference and relates to a series of wider histories, at once aesthetic, cultural, and social.

|

Take, for example, Identical Twins (1967) by Diane Arbus (1923- 71). This is one of her least contentious images, and on the surface at least appears to be quite straightforward. It is, so to speak, what it says it is: an image of identical twins. But as we look at it and begin to read it, so the assumed certainty of its subject-matter gives way before an increasing series of quizzical aspects which, in the end, make this an image exemplary of the difficult nature of photographic meaning.

To begin with, the notion of identical twins suggests the very mirror-like resemblance granted to the daguerreotype in the nineteenth century, and underscores the idea of a photograph as a literal record. Each twin is a reflection of the other. But 'identical' infers 'identity', and the portrayal of a self limited to the surface presence of a single image. The two aspects open up a critical gap between what we 'see' in the photograph and what we are asked to 'view'. The questions raised are made more insistent by the way in which both figures are framed within a photographic space which denies them any obvious historical or social context. We cannot place them in time or space, and there are few clues as to their social or personal background. Arbus has effectively neutralised their terms of existence. The background is white: a painted wall and a path run across the bottom of the image. And yet the path, as a presence, establishes the terms by which we can establish, both literally and symbolically, the basis of our reading of the image. The path runs at a slight angle, and that 'angle' reflects precisely Arbus's approach to her subject-matter. This photograph does not meet its subject in a parallel sense, but looks at it askew, even askance. Thus, what the image begins to reflect is that, like a language, its meanings work not through similarity but through difference. The more we look at the image, moving over its space in time, so the more the merest detail assumes a larger resonance as an agent of identity. And yet we are left with such a pervasive sense of difference as to belie the certainty of the tide. |

Diane Arbus Identical Twins, 1967 Arbus's image is deceptively simple and belies its implicit complexity. On one level it is an exemplary Arbus photograph and reflects her concern with identity. But it is also about difference, and the act of looking (and judgement). In many ways it can be viewed as a visual essay on the nature of photographic meaning.

|

Even on a basic level such difference is vital. One twin is 'happy' and one is 'sad'; the noses are different, the faces are different; their collars are a different shape, the folds of the dresses are different, the length of the arms different, their stockings are different. All, it seems is similar but equally all is different. Eyebrows, fringes, hair, and hairbands are different. The more we continue to look, the more the merest detail resonates as part of a larger enigmatic presence and tension as to what, exactly, we are being asked to look at. Far from identical, these are individuals in their own right. They are, as it were, very different twins.

Identical Twins, then, recalls us to a consideration of the implicit complexity of the photographic message. But it also underlines the extent to which we must be aware of the photographer as arbiter of meaning, and namer of significance. Every photograph is not only surrounded by a historical, aesthetic, and cultural frame of reference but also by an entire invisible set of relationships and meanings relating to the photographer and the point at which the image was made. Part of any reading of this image would involve a knowledge of the work of Arbus and, in turn, her photographic philosophy. We could place it in relation to her oeuvre as a whole, allowing its difference and similarity to other images to determine the terms by which we read it. We might note specific influences upon Arbus (for example, the work of Weegee and Lisette Model), as well as a penchant for particular kinds of subject-matter. Photographs by major photographers might be said to elicit a particular style in the same way that any author exhibits a style of writing that we come to recognise. In this sense we can view the photographer as an auteur, and the work as the summation of a visual style in which content and form are the visual reflection of a photographic discourse and grammar, as much as they are in writing and film. Although this is to the fore in relation to the photographer as artist, literally signing, so to speak, each image with the mark of creative authenticity, it equally recalls to us the extent to which every image is part of a self-conscious and determining act of reference to give meaning to things. The image is as much a reflection of the 'I' of the photographer as it is of the 'eye' of the camera.

In any image, however, the primary frame of reference remains the subject of the photograph (although this in itself can be problematic). Roland Barthes has suggested an important distinction here between the relative meaning of different elements within the photographic frame, distinguishing between what has been termed the denotative and the connotative. By 'denotative' is meant the literal meaning and significance of any element in the image. A gesture, an expression, an object remains just that - a literal detail of the overall image. Meaning thus operates at the most basic of levels, a simple recognition of what we look at: a smile, a table, a street, a person. But beyond this moment of recognition the reader moves to a second level of meaning, that of the 'connotative' aspects of the elements of the scene. Thus connotation is 'the imposition of second meaning on the photographic message proper' ... 'its signs are gestures, attitudes, expressions, colours, and effects endowed with certain meanings by virtue of the practice of a certain society'. In other words, series of visual languages or codes which are themselves the reflection of a wider, underlying process of signification within the culture.

In any image, however, the primary frame of reference remains the subject of the photograph (although this in itself can be problematic). Roland Barthes has suggested an important distinction here between the relative meaning of different elements within the photographic frame, distinguishing between what has been termed the denotative and the connotative. By 'denotative' is meant the literal meaning and significance of any element in the image. A gesture, an expression, an object remains just that - a literal detail of the overall image. Meaning thus operates at the most basic of levels, a simple recognition of what we look at: a smile, a table, a street, a person. But beyond this moment of recognition the reader moves to a second level of meaning, that of the 'connotative' aspects of the elements of the scene. Thus connotation is 'the imposition of second meaning on the photographic message proper' ... 'its signs are gestures, attitudes, expressions, colours, and effects endowed with certain meanings by virtue of the practice of a certain society'. In other words, series of visual languages or codes which are themselves the reflection of a wider, underlying process of signification within the culture.

Identical Twins, then, recalls us to a consideration of the implicit complexity of the photographic message. But it also underlines the extent to which we must be aware of the photographer as arbiter of meaning, and namer of significance. Every photograph is not only surrounded by a historical, aesthetic, and cultural frame of reference but also by an entire invisible set of relationships and meanings relating to the photographer and the point at which the image was made. Part of any reading of this image would involve a knowledge of the work of Arbus and, in turn, her photographic philosophy. We could place it in relation to her oeuvre as a whole, allowing its difference and similarity to other images to determine the terms by which we read it. We might note specific influences upon Arbus (for example, the work of Weegee and Lisette Model), as well as a penchant for particular kinds of subject-matter. Photographs by major photographers might be said to elicit a particular style in the same way that any author exhibits a style of writing that we come to recognise. In this sense we can view the photographer as an auteur, and the work as the summation of a visual style in which content and form are the visual reflection of a photographic discourse and grammar, as much as they are in writing and film. Although this is to the fore in relation to the photographer as artist, literally signing, so to speak, each image with the mark of creative authenticity, it equally recalls to us the extent to which every image is part of a self-conscious and determining act of reference to give meaning to things. The image is as much a reflection of the 'I' of the photographer as it is of the 'eye' of the camera.

In any image, however, the primary frame of reference remains the subject of the photograph (although this in itself can be problematic). Roland Barthes has suggested an important distinction here between the relative meaning of different elements within the photographic frame, distinguishing between what has been termed the denotative and the connotative. By 'denotative' is meant the literal meaning and significance of any element in the image. A gesture, an expression, an object remains just that - a literal detail of the overall image. Meaning thus operates at the most basic of levels, a simple recognition of what we look at: a smile, a table, a street, a person. But beyond this moment of recognition the reader moves to a second level of meaning, that of the 'connotative' aspects of the elements of the scene. Thus connotation is 'the imposition of second meaning on the photographic message proper' ... 'its signs are gestures, attitudes, expressions, colours, and effects endowed with certain meanings by virtue of the practice of a certain society'. In other words, series of visual languages or codes which are themselves the reflection of a wider, underlying process of signification within the culture.

In any image, however, the primary frame of reference remains the subject of the photograph (although this in itself can be problematic). Roland Barthes has suggested an important distinction here between the relative meaning of different elements within the photographic frame, distinguishing between what has been termed the denotative and the connotative. By 'denotative' is meant the literal meaning and significance of any element in the image. A gesture, an expression, an object remains just that - a literal detail of the overall image. Meaning thus operates at the most basic of levels, a simple recognition of what we look at: a smile, a table, a street, a person. But beyond this moment of recognition the reader moves to a second level of meaning, that of the 'connotative' aspects of the elements of the scene. Thus connotation is 'the imposition of second meaning on the photographic message proper' ... 'its signs are gestures, attitudes, expressions, colours, and effects endowed with certain meanings by virtue of the practice of a certain society'. In other words, series of visual languages or codes which are themselves the reflection of a wider, underlying process of signification within the culture.

|

As we shall see, this distinction underlies the meaning of the photograph at every level, and draws into our reading of the image every detail, for everything, potentially, is of significance. On a wider level it informs the terms by which we classify and understand a photograph; for as in painting and literature, each genre has its own conventions and terms of reference. Landscape, portraiture, documentary, art photography - all imply a series of assumptions, of meanings, accepted (and sometimes questioned) as part of the signifying process: a photograph (via the photographer) can reaffirm or question the world it supposedly mirrors. In relation to this critical context, Barthes (in Camera Lucida) has established a further distinction in the way we read the photograph. In discussing the photographic message, he identifies two distinct factors in our relationships to the image. The first, what he calls the studium, is 'a kind of general, enthusiastic commitment', while the second, the punctum, is a 'sting, speck, cut, little hole'. The difference is basic, for studium suggests a passive response to a photograph's appeal; but punctum allows for the formation of a critical reading. A detail within the photograph will disturb the surface unity and stability, and, like a cut, begin the process of opening up that space to critical analysis. Once we have discovered our punctum we become, irredeemably, active readers of the scene.

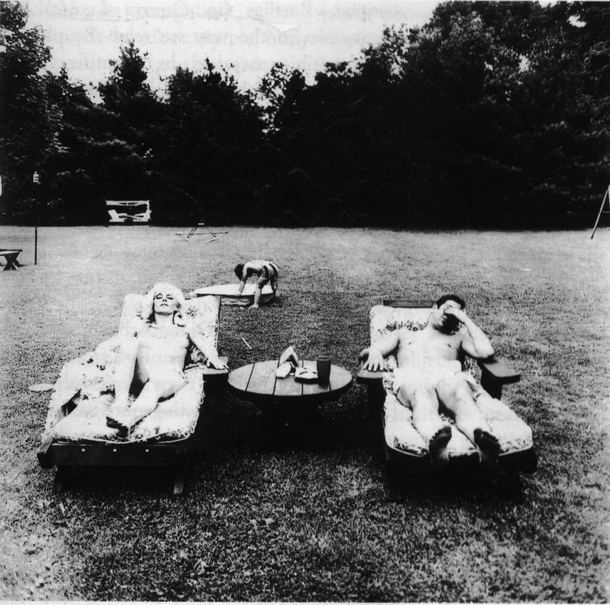

Look at a second Diane Arbus image, A Family on their Lawn One Sunday in Westchester, New York (1969). On the surface this is an image of an average New York suburban middle-class American family, but once again, the more we look at it the more its meaning changes, until it emerges not just as a definitive Arbus image, but as an almost iconic statement on the nature of suburban America. Spatially, for example, the geometry of the image is crucial. The lawn takes up two-thirds of the photographic space and indicates precisely the sense of emptiness, sterility, and dislocation that pervades the image. |

Diane Arbus A Family on Their Lawn One Sunday in Westchester, New York, 1969 Another archetypal Arbus Image which, highly symbolic In Its language, presents what might be seen as a general Image of American culture. It remains an example of the way a single photograph can represent a larger condition, at once cultural, social, and, In this Instance, psychological.

|

Equally, the trees at the back have a looming presence that suggests a haunting otherness. Even at this level the atmosphere seems gloomy, empty, and depressing. A literal, physical configuration has given way to the beginnings of a compelling connotative register suggestive of a psychological and emotional inner space. This is the setting for the figures in the image. The parents are separate and alone, and every detail of their figures and bearing adds to this sense of difference. The man is tense (rather than relaxed, as we might expect) and holds his head in his hand. His right hand looks to touch and make contact with his wife, but remains inert and separate. The mother also 'relaxes' but in a seemingly 'fixed' mode, just as she is dressed in a stereotypical bikini and wears make-up. Their separation is made obvious by the way in which their lounge chairs are presented formally to the camera, with the round table between them: a circular reminder of unity and wholeness, although the slatted lines imply a rigid familial and psychological geometry - a connotation further suggested by the solitary child who stares into a circular bathing pool.

The boy plays alone and is turned away from his parents. The title itself 'frames' our terms of reference and guides us into the symbolic structure of the photographic message. Punctum follows punctum, so that each aspect resonates as part of a larger map of meaning, especially in relation to the associations implied by 'family', 'Sunday', and 'lawn'. An image of family relaxation seems to have been inverted and emerges as a psychological study of estrangement and loneliness which, in its compulsive effect, speaks about a whole culture's condition. Look, for example, how obvious items of play and pleasure have been pushed to the borders of the image. On the left is a picnic table, in the background a swinging seat and see-saw, and on the right a swing; all abandoned and ignored. We could continue such a reading, noting (and explaining) the significance of the cigarettes, the glass, the portable radio, the washed-out sky, the father's dangling feet, the abandoned plate to the left of the mother, and the way the child is closer to his mother than his father: all compounded by the square format of the photograph and the way the family seems unaware of the photographer's presence.

Arbus's image, which is typical of her photography, both plays with and questions codes of meaning. It inculcates a dense play of the denotative and connotative in relation to its subject, and compounds its textual reference within a geometry of the straight and the circular. It is a static image which resonates with multiple meanings and ultimately retains a complexity which resists paraphrase and description.

Photographs have always had this capacity to probe and suggest larger conditions, which underlies the notion of an image's potential 'universal' appeal and international language. Such, for example, were the terms of reference for The Family of Man Exhibition in New York in 1955. Curated by Edward Steichen, its 503 photographs were divided into distinct general categories: 'creation, birth, love, work, death, justice .. . democracy, peace . ..' and so on. The exhibition thus suggested 'universal' themes which mitigated against the argument for a photographic language rooted in the culture as the ideology within which the photograph established its meaning. We can, then, speak of a language of photography, in which every aspect of the photographic space has a potential meaning beyond its literal presence in the picture.

Thus we can read a photograph within its own terms of reference, seeing it not so much as the reflection of a 'real' world as an interpretation of that world. The punctum allows us then to deconstruct, so to speak, those same terms of reference, and alerts us to the fact that a photograph reflects the way we view the world in cultural terms. Photographic practice, though, has in many ways made invisible its strategies and that language, so that we tend to look at the photograph as a reflection - once again, the simple mirror - but on the other hand much photography does seek to make us aware of how and why a photograph has 'meaning'; and in the twentieth century, certainly, many photographers have questioned not just the terms of reference we take for granted but also the codes and conventions of photography itself (e.g. the photographer's status, photographic genres, style, etc.).

The boy plays alone and is turned away from his parents. The title itself 'frames' our terms of reference and guides us into the symbolic structure of the photographic message. Punctum follows punctum, so that each aspect resonates as part of a larger map of meaning, especially in relation to the associations implied by 'family', 'Sunday', and 'lawn'. An image of family relaxation seems to have been inverted and emerges as a psychological study of estrangement and loneliness which, in its compulsive effect, speaks about a whole culture's condition. Look, for example, how obvious items of play and pleasure have been pushed to the borders of the image. On the left is a picnic table, in the background a swinging seat and see-saw, and on the right a swing; all abandoned and ignored. We could continue such a reading, noting (and explaining) the significance of the cigarettes, the glass, the portable radio, the washed-out sky, the father's dangling feet, the abandoned plate to the left of the mother, and the way the child is closer to his mother than his father: all compounded by the square format of the photograph and the way the family seems unaware of the photographer's presence.

Arbus's image, which is typical of her photography, both plays with and questions codes of meaning. It inculcates a dense play of the denotative and connotative in relation to its subject, and compounds its textual reference within a geometry of the straight and the circular. It is a static image which resonates with multiple meanings and ultimately retains a complexity which resists paraphrase and description.

Photographs have always had this capacity to probe and suggest larger conditions, which underlies the notion of an image's potential 'universal' appeal and international language. Such, for example, were the terms of reference for The Family of Man Exhibition in New York in 1955. Curated by Edward Steichen, its 503 photographs were divided into distinct general categories: 'creation, birth, love, work, death, justice .. . democracy, peace . ..' and so on. The exhibition thus suggested 'universal' themes which mitigated against the argument for a photographic language rooted in the culture as the ideology within which the photograph established its meaning. We can, then, speak of a language of photography, in which every aspect of the photographic space has a potential meaning beyond its literal presence in the picture.

Thus we can read a photograph within its own terms of reference, seeing it not so much as the reflection of a 'real' world as an interpretation of that world. The punctum allows us then to deconstruct, so to speak, those same terms of reference, and alerts us to the fact that a photograph reflects the way we view the world in cultural terms. Photographic practice, though, has in many ways made invisible its strategies and that language, so that we tend to look at the photograph as a reflection - once again, the simple mirror - but on the other hand much photography does seek to make us aware of how and why a photograph has 'meaning'; and in the twentieth century, certainly, many photographers have questioned not just the terms of reference we take for granted but also the codes and conventions of photography itself (e.g. the photographer's status, photographic genres, style, etc.).

|

In part, of course, such codes are central to the photograph's power as an image. Its surface, flat and 'sealed' beneath its gloss coating, presents the image as part of a sealed and continuous world, so that the context in which it was taken remains invisible and outside the frame of the image. A painting, in contrast, has a surface we can identify in terms of paint and brushstrokes. It always reflects the way it was made. Photography, as a medium, is deceptively invisible, leaving us with a seamless act of representation, an insistent thereness in which only the contents of the photograph, its message, are offered to the eye.

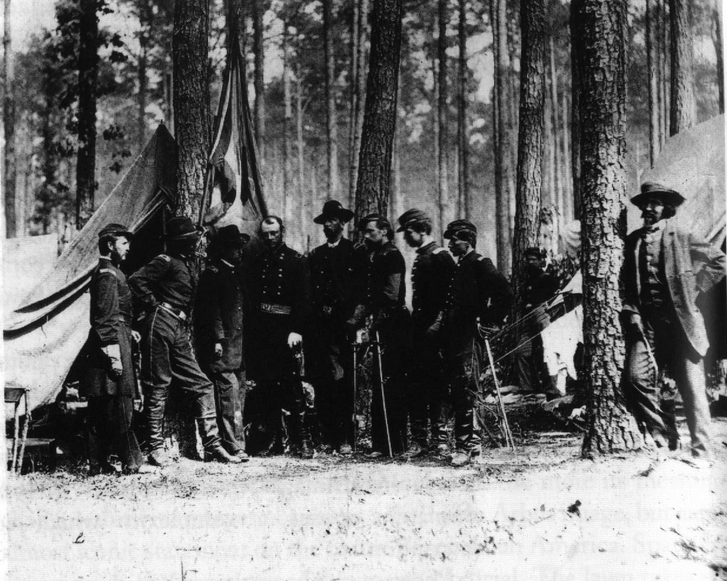

War photography is a case in point, especially in the nineteenth century. TheAmerican Civil War was the most photographed war of its time, with thousands of images documenting its progress in extraordinary detail. This suggests that the camera is a 'witness to events', and yet even at this 'documentary' level the most seemingly neutral of images is subject to the problematic of representation. Look, for example, at Matthew Brady's (1823-96) General Robert Potter and Staff. Matthew Brady Standing by Tree (1865). Brady was one of the foremost of the official photographers of the war, and his images offer a sustained record of events. This one is typical, one of a large number of group photographs in which the Union army's hierarchy pose before the camera. So what makes this image so significant? I think the answer is twofold. First, as a formal picture it takes its place within a larger body of portraiture whose parallel, of course, is in painting. Secondly, the photographer himself is in the image (although many of Brady's images were taken by his assistants). What emerges is two different photographs with two distinct messages. Brady has made himself visible to us and, in so doing, has made photography, as much as the military group, the subject of the image. In such a formal portrait meaning is established though strict codes of significance based on a traditional (military) hierarchy of rank and significance in a male world. If we cut Brady out, then Potter, as the general, becomes the centre of attention and is placed in the middle of the photographic space. His position is reinforced by the way the rest of the group defer to him. They look at him, as do we. Potter, at the centre of the group, is also identified as the symbol of a military code based on honour, courage, and strength. His hairstyle and stance are reminiscent of the way Napoleon was pictured (or painted). Potter seems to offer himself as a representative icon of the military world he controls and of the values for which he stands. But his position is also part of his place in history. This is then, in one sense, a definitive portrait, akin to an oil painting. But as with the Arbus, what begins to emerge on closer scrutiny is a highly stylised and dense register of meaning reflecting the world of the image. The vertical structure reinforces the obvious codes of authority and distinction, merging the straightness of the trees behind with the presence of the figures as they stand before us. Potter is the only figure who does not wear a hat, further distinguishing him from the group and increasing his singular status. His significance is given added 'weight' by the dense frieze-like arrangement of the group, reminiscent of a monumental sculpture. The regalia and insignia complete the impression of power and authority, as distinct symbolic languages in their own right. As such, then, this is a conventional portrait and confirms the values of a military world and the significance of distinguished individuals as they confirm their place in history. But what happens when we include the figure of Brady in the image? Allow Brady's presence on the right to be the object of our attention and immediately Potter is de-centred. |

Matthew Brady General Robert Potter and Staff. Matthew Brady Standing by Tree, 1865 A characteristic portrait from the American Civil War. The central aspect of this photogra ph is the presence of the photogra pher, Matthew Brady, to the right of the official military group. Brady's presence not only questions the terms of photographic meaning, but the values of the system and the subjects photographed. Compare, for example, Brady's stance to that of General Potter. Note also the insistence on the vertical as part of a larger symbolic military and male code.

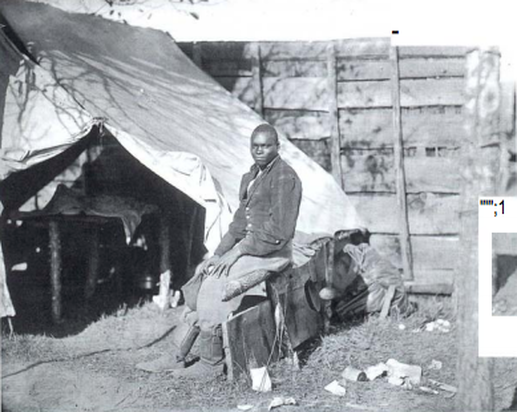

Matthew Brady John Henry, A Well Remembered Servant, 1865 Another Civil War image the reverse of the official portrait. On its own it remains ordinary, but in the context of other images it takes its place within a hierarchy of representation. Thus it questions the terms of reference advertised in [Brady's group portrait above] and draws attention to the position of the black figure within the Union army. The figure's position is compounded by the way in which the smallest object (rubbish, cans, a fence, his clothes) reflects his social position. Every detail signifies something beyond its literal meaning.

|

The compositional balance of the 'first' photograph is completely broken. What emerges is a double structure: an official group portrait which advertises and celebrates a white military world, and a second which, through the simple presence of the photographer, questions the terms of reference of the first. Brady has established a critical distance between himself, the group, and the way the group has been photographed; an aspect further underlined by the way his own pose, nonchalant and casual, is in direct contrast to the others. In terms of Barthes's reading of photographs Brady's presence creates a punctum which begins a process of questioning. Brady, along with such figures asTimothy O'Sullivan and Alexander Gardner, is among the most celebrated of the 'official' war photographers of the period, but once we begin to question the context, the terms of imaging, the treatment of subject, and so on, a very different image of the war emerges, and a very different sense of war photography as an historical account. What such images show us is not so much a history as an ideology, and in their accretion as a composite image they create a sustained photographic essay on that ideology. Collectively they build towards a critical questioning and, far from 'official', they suggest the contradictions and myths at the centre of the culture. Thus, in relation to the General Potter photograph an image like takes its place within a very different tradition of portraiture and history, as a fundamental inversion of the 'official' portrait. This is, literally, the underside of the formal advertising and reveals the Potter image as both propagandist and mythologized. The single figure is isolated, at the margins of the world depicted and at the bottom of the hierarchy. Most obviously he is black, and just as his presence was missing from the white world of Potter's image, so here he is restrained within a domestic context. He is named as a servant, passive, and surrounded by rubbish. His uniform confirms his condition.

Such a critical and self-conscious use of the medium is most often associated with radical twentieth-century photography, especially since the 1950s, when there has emerged a sustained questioning of the terms of representation and the structures of meaning very much influenced by critical theories associated with modernism, and in thepostmodern period, by structuralism and semiotics. But in many ways we need to see all photographs in the same terms and be alert to the extent that photographers have always been concerned with the context of both the photograph and the act of taking it. The illusion of a photograph's veracity is always open to a punctum which allows us to read it critically and to claim it as not so much a token of the real, but as part of a process of signification and representation.

The extent to which many contemporary photographers have questioned the idea of a single representational space and made the reading of the photograph their subject helps to place all photography within the context of postmodern practice. The irony that photography achieved its ascendency as a visual medium confirming a real world just at the point when literature and painting were rejecting the aims and assumptions of realism, is tempered once we agree to a theory of photographic meaning as being as problematic as anything we find in such works as The Waste Land, Ulysses, or Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Just as Wallace Stevens declared that in modern poetry the subject was 'poetry itself', so in painting the act of representation itself became central. Photography has followed a similar development, creating the terms for a critical reading of its meaning and status as a mode of representation. One such photographer is the American Lee Friedlander (1934 - ). Friedlander's photographs are deliberately difficult to read, indeed, they make difficulty basic to their meaning as part of a larger critical process. The question of the terms by which we read a photograph, and the status of the world it 'reflects' are central to his whole enterprise. His eye roams the United States not as a Walker Evans intent on a vision of a particular cultural order, but as the recorder of a series of random events and images which, once questioned, fail to cohere. What emerges is a disparate world of chaotic images and signs, signifying processes in which everything hovers about meaning but finally only declares itself as part of a larger problematic structure. And within this process the photograph directly implicates us in the act of reading. It neither draws us into its assumed space, nor mirrors back a world which affirms our own terms of reference. Instead, it purposefully distorts the world we take for granted and makes the photographic act part of a larger way of seeing and constructing meaning. His images are not so much a record of what is, as visual essays on cultural representation. Highly self-conscious, they work through paradox, the play of absence and presence, radical perspectives, and the breaking up of the photographic surface to create new and difficult relationships.

Such a critical and self-conscious use of the medium is most often associated with radical twentieth-century photography, especially since the 1950s, when there has emerged a sustained questioning of the terms of representation and the structures of meaning very much influenced by critical theories associated with modernism, and in thepostmodern period, by structuralism and semiotics. But in many ways we need to see all photographs in the same terms and be alert to the extent that photographers have always been concerned with the context of both the photograph and the act of taking it. The illusion of a photograph's veracity is always open to a punctum which allows us to read it critically and to claim it as not so much a token of the real, but as part of a process of signification and representation.

The extent to which many contemporary photographers have questioned the idea of a single representational space and made the reading of the photograph their subject helps to place all photography within the context of postmodern practice. The irony that photography achieved its ascendency as a visual medium confirming a real world just at the point when literature and painting were rejecting the aims and assumptions of realism, is tempered once we agree to a theory of photographic meaning as being as problematic as anything we find in such works as The Waste Land, Ulysses, or Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Just as Wallace Stevens declared that in modern poetry the subject was 'poetry itself', so in painting the act of representation itself became central. Photography has followed a similar development, creating the terms for a critical reading of its meaning and status as a mode of representation. One such photographer is the American Lee Friedlander (1934 - ). Friedlander's photographs are deliberately difficult to read, indeed, they make difficulty basic to their meaning as part of a larger critical process. The question of the terms by which we read a photograph, and the status of the world it 'reflects' are central to his whole enterprise. His eye roams the United States not as a Walker Evans intent on a vision of a particular cultural order, but as the recorder of a series of random events and images which, once questioned, fail to cohere. What emerges is a disparate world of chaotic images and signs, signifying processes in which everything hovers about meaning but finally only declares itself as part of a larger problematic structure. And within this process the photograph directly implicates us in the act of reading. It neither draws us into its assumed space, nor mirrors back a world which affirms our own terms of reference. Instead, it purposefully distorts the world we take for granted and makes the photographic act part of a larger way of seeing and constructing meaning. His images are not so much a record of what is, as visual essays on cultural representation. Highly self-conscious, they work through paradox, the play of absence and presence, radical perspectives, and the breaking up of the photographic surface to create new and difficult relationships.

|

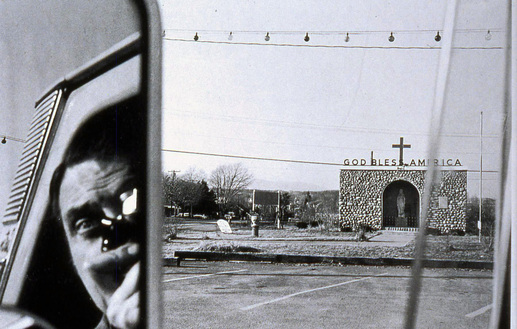

Thus Friedlander makes the act of reading basic. One of his most famous images, for example, Route 9W New York (1969), includes a reflection of the photographer in the wing-mirror of his car as he takes a photograph at the scene on which we look. It is definitive Friedlander territory - a visual space in which the theoretical is central to the scene/seen. The very act of looking is displaced as part of a larger process of construction. The mirror establishes a self-reflexive term of reference, and opens up the image to a complex and ambivalent photographic and cultural discourse. The mirror is, in fact, basic to Friedlander's effect, for he will not just, Brady-like, include himself in the scene/seen, but makes reflections, shadows, part of a radical symbolic presence.

The process is similar in another exemplary Friedlander image, Albuquerque (1972) One of a number of images of America, this could be anywhere and nowhere. At first glance it appears as a bland and nondescript image, but then begins to resonate with a rich and profuse meaning. In characteristic manner Friedlander has broken up the surface of the photograph so that an ordered, three-dimensional space is simultaneously questioned and altered. We look not at Albuquerque but at a photograph. It resists any single focal point, so that our eye moves over and over the image without any point of rest, any settled or final sense of unity (and unitary space and meaning). It photographs the most obvious of urban things: a block of flats, a dog, a fire-hydrant, a car, a road, and yet fuses them into an enigmatic series of connections. Friedlander makes the familiar unfamiliar, and the obvious strange. In this image, for example, there is no sense of depth, so that everything exists in a two-dimensional rather than three-dimensional perceptual space. Any 'depth' exists in relation to the conceptual density of the image. In a connotative context, we note how the image is saturated with signs of communication. A sterile scene is glutted with the process of possible connections: the car, the road, the telegraph wires, and the traffic-lights. And of course the act of communicating, the lines of meaning, are part of the photograph's subject. Friedlander thus creates a photographic space which makes critical analysis and cultural meaning the world of its imaging. Just as his discontinuous and deceptive images make central the language and syntax of the photograph, so they often exhaust the subject in order to reduce it to little more than a marginal and banal presence. The most obvious and marginal subject often resonates as part of an on-going ambiguity and difficulty. In short, they offer us exemplary images for how we read a photograph and how the photograph constructs meaning. Friedlander's images change the history of the photograph and give us a critical vocabulary by which to read its development. |

Lee Friedlander Route 9W New York, 1969 A self reflexive image typical of Friedlander's style and approach, Here the single unified space of the photograph has been broken up into a series of different directions, perspectives, and potential meanings, The image is full of signs and symbols which remain enigmatic. All is de-centred as part of a larger problematic of mean.

Lee Friedlander Albuquerque. 1972

Although a somewhat banal image. this is deceptively complex and almost gluts the eye with images of implied communication. All the elements of the image remain on the edge of meaning. The atmosphere is one of emptiness. The photograph is a distinctive statement about contemporary America. |

They return to the basic distinctions between the denotative and connotative so insisted upon by Barthes and Umberto Eco and make clear that, as much as in painting and literature, the meaning and practice of photography takes place within its own series of codes and frames of reference. When Barthes declared that photography 'evades us' and is 'unclassifiable', he alerted us to the paradox of something seemingly so obvious and yet so problematic.

Source

Source