Some initial questions:

- If you could only keep a physical copy of one photograph, which would it be and why?

- What motivates you to take photographs?

- In what sense are your photographs an attempt to stop time?

- Would you rather have a photograph or a video/film of an important event in your life? Why?

The content of every photograph is history. It shows the moment of the image's origin that is always in the past to the moment in which it is viewed. Even the instantaneity of the polaroid photograph captures a scene or event that can have transformed beyond recognition before the image is developed. However contrived, however still the scene, a photograph offers us a glimpse of actions and events that have already occurred and which, usually, are finished. The photographic image, unlike the filmic image, does not easily show the passage of time but it does show us that time has passed [...] What photographs do is to bring the past into the present, confronting us with the passage of time and the stillness of that which has gone.

-- Tim Dant & Graeme Gilloch, Pictures of the Past: Benjamin and Barthes on photography and history, 2002

Shadows fixed forever

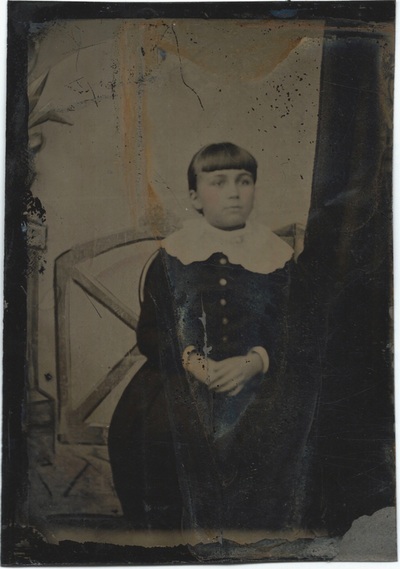

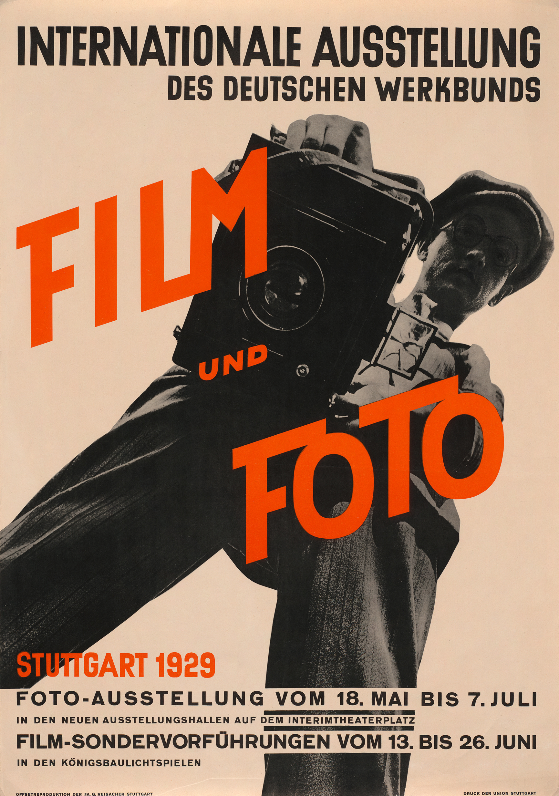

In the early 19th century, before the invention of photography, anyone wishing to leave a visual representation of themselves to posterity had to rely on a painted portrait. These took time to create and were too expensive for most people. Photography, in particular the Daguerrotype, provided more people with a means to create a likeness of themselves or a family member - a reminder of the way they looked at a certain time that would outlive them. (TC#1)

I long to have a memorial of every being dear to me in the world. It is not merely the likeness which is precious in such cases--but the association and the sense of nearness involved in the thing...the fact of the very shadow of the person lying there fixed forever! ...I would rather have such a memorial of one I dearly loved, than the noblest artist's work ever produced. This ability of the photograph to record the light reflected off a living (or dead) body made it seem an even better way to capture the essence of the subject. Given the high mortality rate in the 19th century it's no wonder that photographs of dead children are common, often posed in such a way as to appear still living.

Photographs appear to be instantaneous. We think of photographs as stills, frozen in time. And yet each photograph contains a "parcel of time", to use John Szarkowski's beautiful phrase. Photography is, in part, a time based medium and yet its relationship to time is fraught and complex. How do photographs inform us (and deceive us) about the past, present and future? |

The long lost past minute where the future is nesting

In appearing to stop time, so that we can examine a moment from the past for as long as we like, photographs are unlike any other media or art form. What makes a photograph different to a painting or a film of the same event?

|

In his famous essay A Short History of Photography (1931), Walter Benjamin contemplates this photograph by Hill and Adamson. He compares the effect of looking at a photograph like this to an imaginary painting of a similar subject. What is it that makes the photograph "something strange and new"?

in that fishwife from Newhaven who looks at the ground with such relaxed and seductive shame something remains that does not testify merely to the art of the photographer Hill, something that is not to be silenced, something demanding the name of the person who had lived then, who even now is still real and will never entirely perish into art. Benjamin is transfixed by the "exact technique" of photography and its ability to communicate a "magical value" caused by "the tiny spark of accident, the here and now." (TC#6)

In such a picture, that spark has, as it were, burned through the person in the image with reality, finding the indiscernible place in the condition of that long lost past minute where the future is nesting, even today, so eloquently that we looking back can discover it. Photographs warp our sense of time, collapsing the past in the present, capturing what has been lost but which still exists. The long exposure used to make this photograph, perhaps causing the particular concentration of the sitter's expression, makes her gaze seem even more intense, more 'real'. And yet we know that she is long dead, as is the photographer who created her likeness.

|

Clocks for Seeing

|

Photographs warp our sense of time. All photographs present us with the past and present at the same time. Photographs remind us of people and things that have gone. Photographs record what has been lost, what no longer exists, or what still exists but will be lost at some point in the future. In his book Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes writes about time and photography:

For me the noise of Time is not sad: I love bells, clocks, watches — and I recall that at first photographic implements were related to techniques of cabinetmaking and the machinery of precision: cameras, in short, were clocks for seeing. |

In his search for a "just" picture of his mother, recently deceased, Barthes stumbles across one of her taken when she was five years old. The photograph is not reproduced in the book since he claims that its special meaning (the punctum) would be lost on any other viewer than himself. Barthes is shocked that this photograph of a little girl is proof both that his mother had lived and that she is now dead. The photograph is a "catastrophe which has already occurred." Photographs can enable a kind of time travel in which the past, the present and the future seem to co-exist.

Exposure time

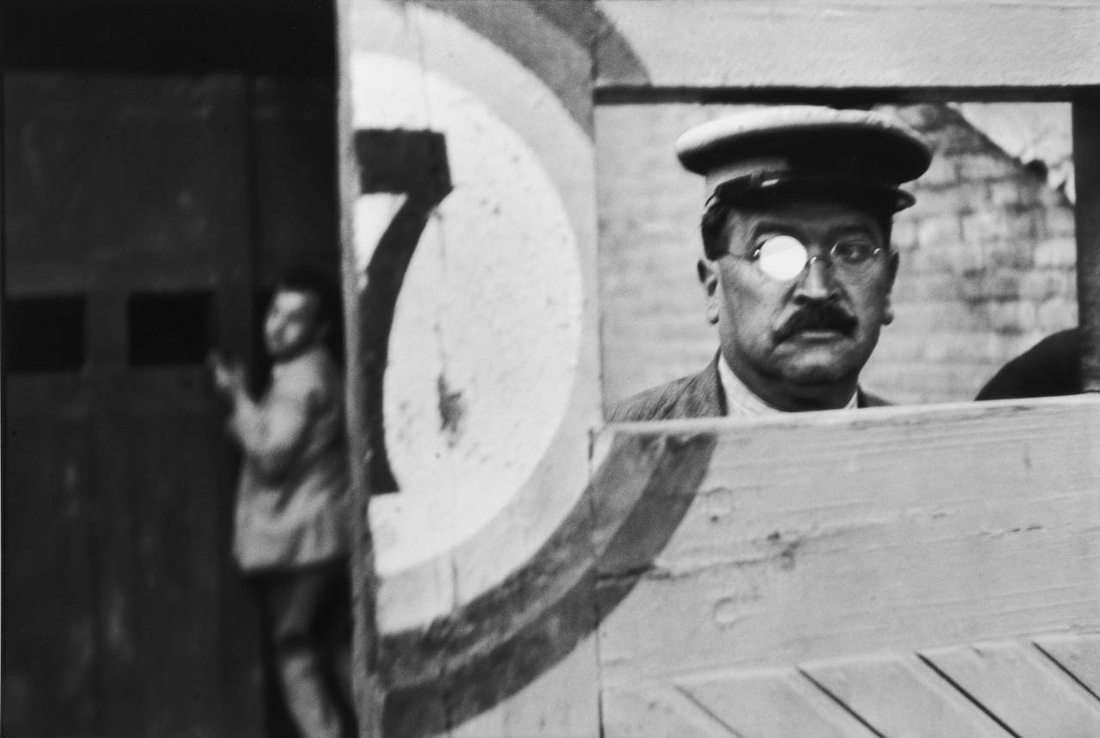

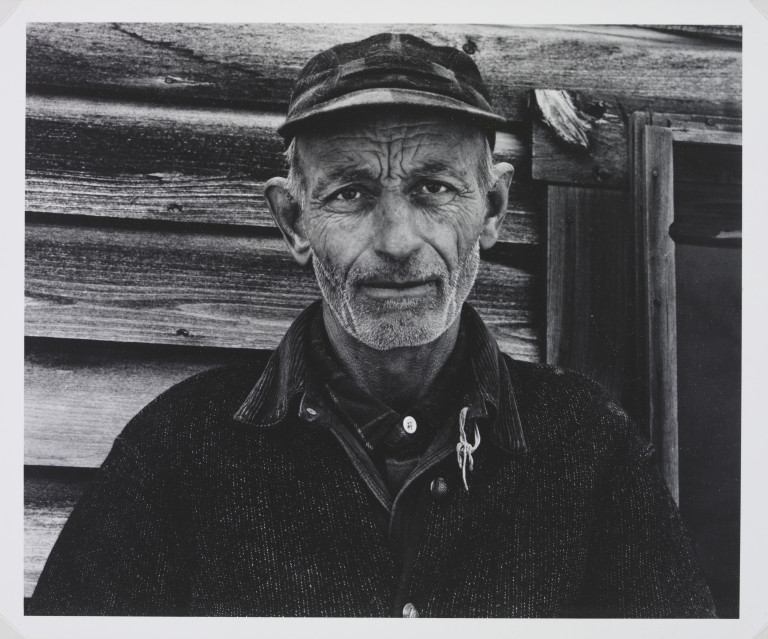

Consider these two famous photographs:

What do you notice about the way the subjects have been photographed? Think about some of the issues raised by TC#8, the visual language or 'grammar' of photography. Or perhaps you may wish to consider issues of genre (TC#1), light (TC#2), selection (TC#4) or chance (TC#6). What are the important similarities and differences between these two photographs?

John Berger writes about both these photographs in an essay about Paul Strand from 1972. He thinks about them in terms of time. He claims that Strand's approach is the opposite of Cartier-Bresson's:

John Berger writes about both these photographs in an essay about Paul Strand from 1972. He thinks about them in terms of time. He claims that Strand's approach is the opposite of Cartier-Bresson's:

The photographic moment for Cartier-Bresson is an instant, a fraction of a second, and he stalks that instant as though it were a wild animal. The photographic moment for Strand is a biographical or historic moment, whose duration is ideally measured not by seconds but by its relation to a lifetime. Strand does not pursue an instant, but encourages a moment to arise as one might encourage a story to be told.

-- Jon Berger, Paul Strand, 1972 (from About Looking)

Berger goes on to explain that this involves Strand making a series of decisions before he takes the photograph, rejecting the accidental, working deliberately, avoiding cropping, working with a large format camera (instead of a small, silent rangefinder). Berger makes a rather strange claim. He suggests that Strand's subjects are transformed into narrators and that the camera is listening to them so that "one has the strange impression that the exposure time is the lifetime."

Suggested activities:

- Explore the notion of the Decisive Moment and its opposite, the Indecisive Memento. You could compare the process of capturing photographs like Cartier-Bresson which require the cohesion of visual elements in a split second with an attempt to photograph in between moments, boredom or nondescript events.

- Attempt to make one or more photographic portraits, influenced by Paul Strand, that tell a story about the sitter. Think carefully about your point of view, the location, the quality of the light, your choice of lens, your sitter's pose and expression. Is it possible to capture the sense of a lifetime of experience in a single photograph?

Histoires de poussière

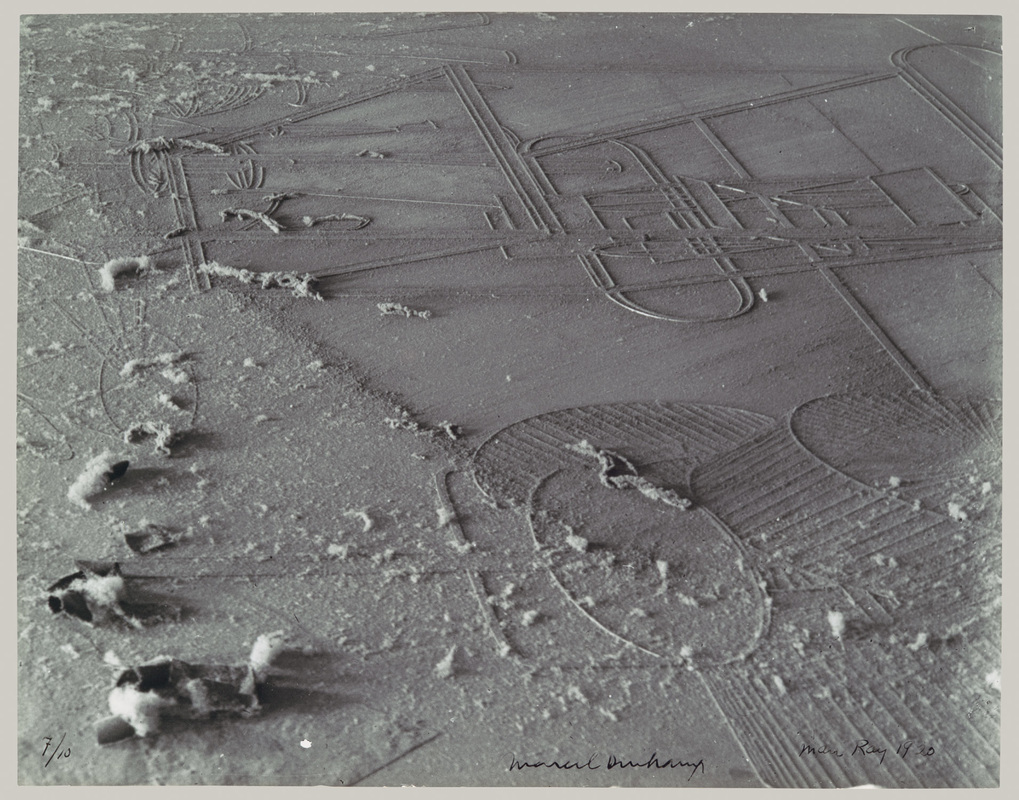

Take a look at the image below. What do you see? You could ask yourself, or your students, the following questions:

- How far away from the subject is the camera?

- What explains the existence of the marks and other objects/materials we can see?

- What and where is the light source?

- What might lie beyond the edges of the photograph?

- Why might there be two separate signatures on the print?

- If you could choose, what title would you give this picture?

|

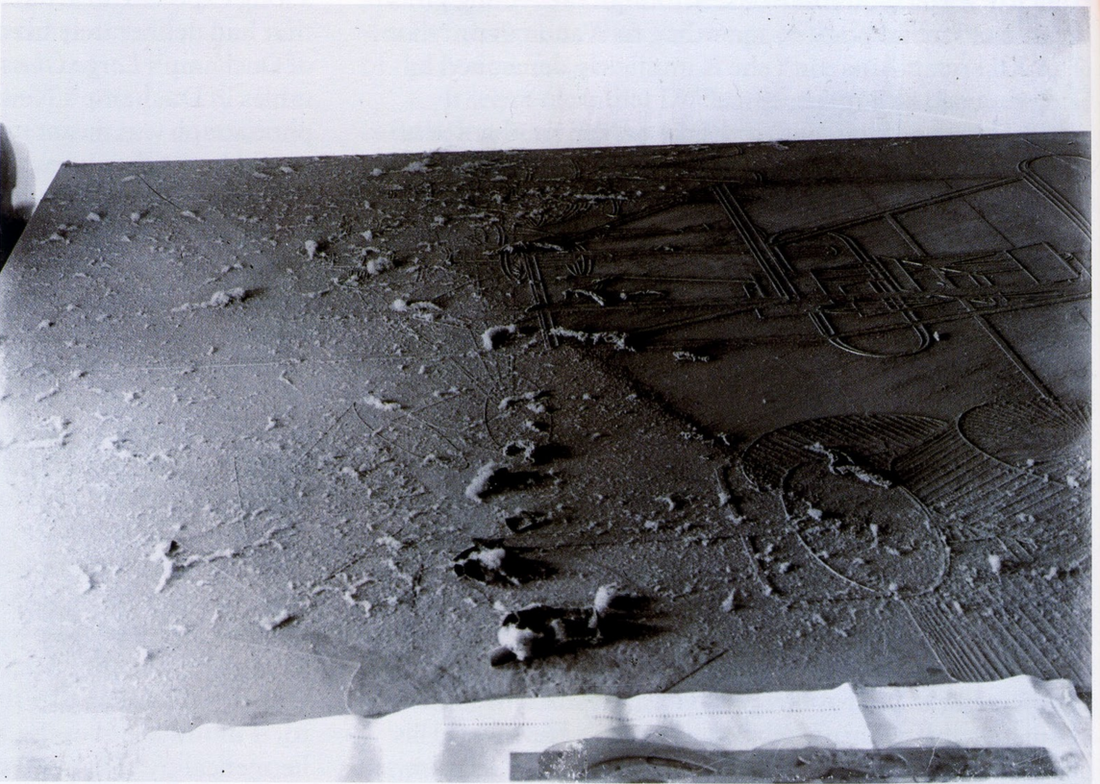

I often use this photograph as an exercise in visual analysis with my A level photography students. If you are familiar with it you will perhaps know some of the historical and technical context. It is one of the most enigmatic photographs in the history of photography with a fascinating legacy. The version above is heavily cropped. You can see on the right that the negative contains some significant contextual information. By removing the edges of the object and zoning in on the odd textures and patterns in the bottom right hand corner, Man Ray deliberately confuses our sense of time and space. However, two facts about the picture help us to make sense of it:

If you are interested in exploring the history of photography's relationship to dust (and time) I strongly recommend getting hold of David Campany's wonderful book.

|

Suggested activities:

- Think carefully about what you can see in the world around you and subjects that remind you of time having passed - peeling walls, rust, layers of graffiti, smudged whiteboards, rotten fruit, faded clothes, marks, stains and traces of various sorts etc.

- Attempt to make a single still photograph that suggests the passage of time. You may wish to make several different photographs of this subject, choosing the one that you think best captures the idea of time. To crop or not to crop...? (TC#8) Will you give your image a title or caption? (TC#9)

The delayed rays of a star

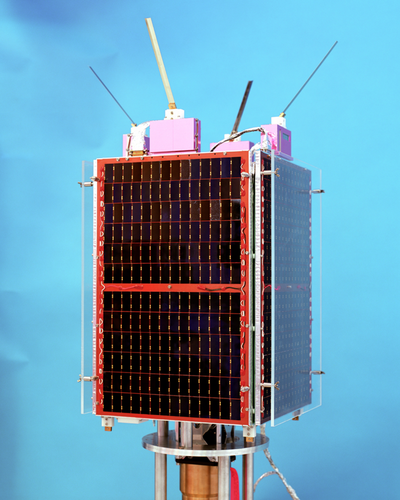

Light travels at 300,000 km per second. It takes 8 minutes for light from the Sun to reach Earth. When you look into the sky, you are seeing the Sun as it was 8 minutes ago. Photographs capture this light from the past. All photographs are in some way relics, evidence of what once existed but has been lost. They also foretell of losses to come.

Susan Sontag considered all photographs to be memento mori, reminders of death. Towards the end of her book 'On Photography' she refers to the story of a Daguerrotype of the star Vega, the light from which had taken 20 years to reach the Earth. The photograph was taken by astronomers in Cambridge in 1850. Sontag quotes the painter Eugene Delacroix who noted in his journal that the light from the star pre-dated the invention of the Daguerrotype process. In other words, when the light left the star, way out in space, the art of photography had not yet been invented but by the time the light reached Earth, humans had found a way to fix it forever.

Susan Sontag considered all photographs to be memento mori, reminders of death. Towards the end of her book 'On Photography' she refers to the story of a Daguerrotype of the star Vega, the light from which had taken 20 years to reach the Earth. The photograph was taken by astronomers in Cambridge in 1850. Sontag quotes the painter Eugene Delacroix who noted in his journal that the light from the star pre-dated the invention of the Daguerrotype process. In other words, when the light left the star, way out in space, the art of photography had not yet been invented but by the time the light reached Earth, humans had found a way to fix it forever.

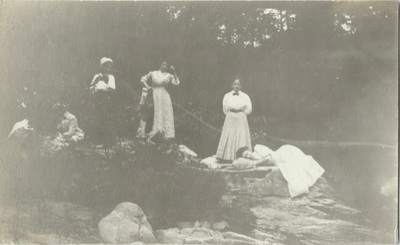

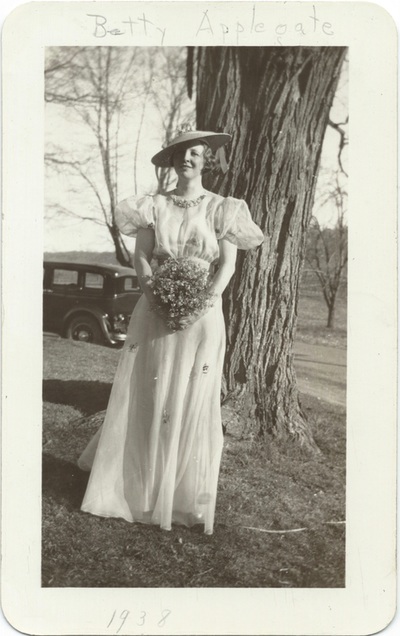

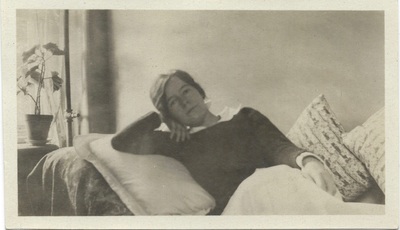

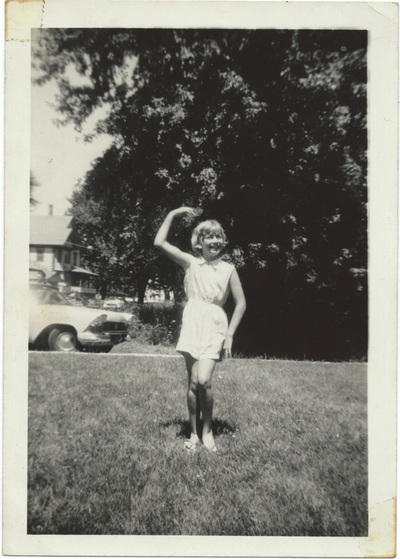

Most photographs aren't made by photographers or artists but by ordinary amateurs, documenting their daily lives. This summer, on holiday in the USA, I discovered a cache of old photographs in a flea market in (the coincidentally named) Silver Lake, NH. As I leafed through the photographs, presumably taken from old family albums, I was struck by several portraits. Here are those that I bought, for a few dollars, from the grizzled old proprietor:

Why did these old photographs affect me so? What caused them to reach out across the years to grab my attention, to make me look and wonder? From the late nineteenth century studio tin type to scenes of beaches, fields, front parlours, porches and back gardens, each of these images conjures a lost world of light, almost real, forever frozen. In two images the photographer is visible (as a car door reflection and a shadow projected across the porch floor). In all of them the sitter is aware of being photographed and we, contemporary viewers, are now stand ins for the photographer. The lady with the parasol, has a serious, questioning expression that suggests a mild annoyance. The people in each of these photographs, the young women posing by the river, the children (and the farm cat) climbing on the wagon and Betty Applegate in her wedding dress, the year before the outbreak of WW2, are separated from us by a chasm of time. And yet photographs have the extraordinary ability to capture those little details - a curious gesture, an object out of place, the hang of fabric, the quality of light - that suggest a living (or lived) presence. As noted by Roland Barthes, the realisation that the subject, who appears so full of life in the photograph, is now long dead comes as a shock:

One day, quite some time ago, I happened on a photograph of Napoleon’s youngest brother, Jérôme, taken in 1852. And I realised then, with an amazement I have not been able to lessen since: ‘I am looking at eyes that looked at the Emperor.’ Sometimes I would mention this amazement, but since no one seemed to share it, nor even to understand it (life consists of these little touches of solitude), I forgot about it [...] The photograph is literally an emanation of the referent. From a real body, which was there, proceed radiations which ultimately touch me, who am here; the duration of the transmission is insignificant; the photograph of the missing being, as Sontag says, will touch me like the delayed rays of a star.

-- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida

A photograph, especially one from the distant past, is a reminder of what has been lost. The photograph of the young girl above, laughing on the lawn, touches us because we realise that she will not escape mortality. Sontag's view is that photography is "an elegiac art, a twilight art. Most subjects photographed are, just by virtue of being photographed, touched with pathos."

Back to the Future

Whilst photography has always been about telling lies as much as it has also strived to tell the 'truth', digital techniques allow contemporary artists to interfere with the theoretically direct relationship between subject and image, time and place (TC#8). This documentary presents the practice of Irina Werning whose Back to the Future project re-stages old photographs, a strategy used for autobiographical purposes by photographer Chino Otsuka in her series Imagine finding me.

Suggested activities:

- Explore photographs from old family albums. Search for old family portraits of people to whom you are related but have never known. Write about these pictures and how you feel about them.

- Locate photographs of you as a child. Re-enact these scenes, attempting to mimic the poses, gestures, settings and mood of the originals. Conversely, digitally insert yourself into imaginary scenes of the future, either your own or that of the planet.

- If you could only leave behind one image of yourself, for others to remember you, which would it be and why? Create a new self-portrait that captures not only the way you look but aspects of your character, interests, achievements and ambitions.

Stopping time

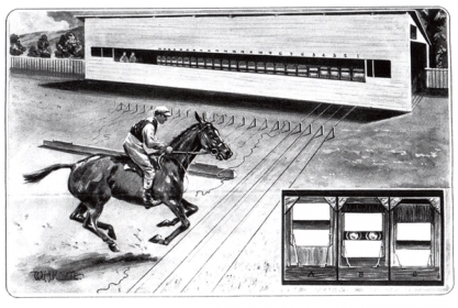

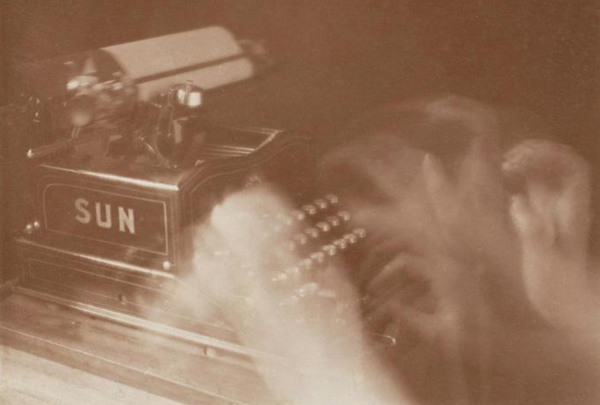

The subject of some photographs appears to be time itself. Quite early in the history of photography, practitioners began to experiment with the camera's ability to alter our relationship to time through a range of ingenious strategies.

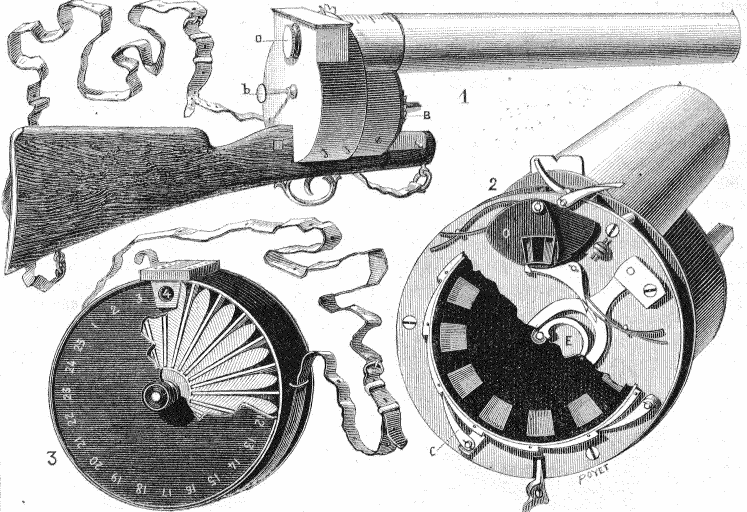

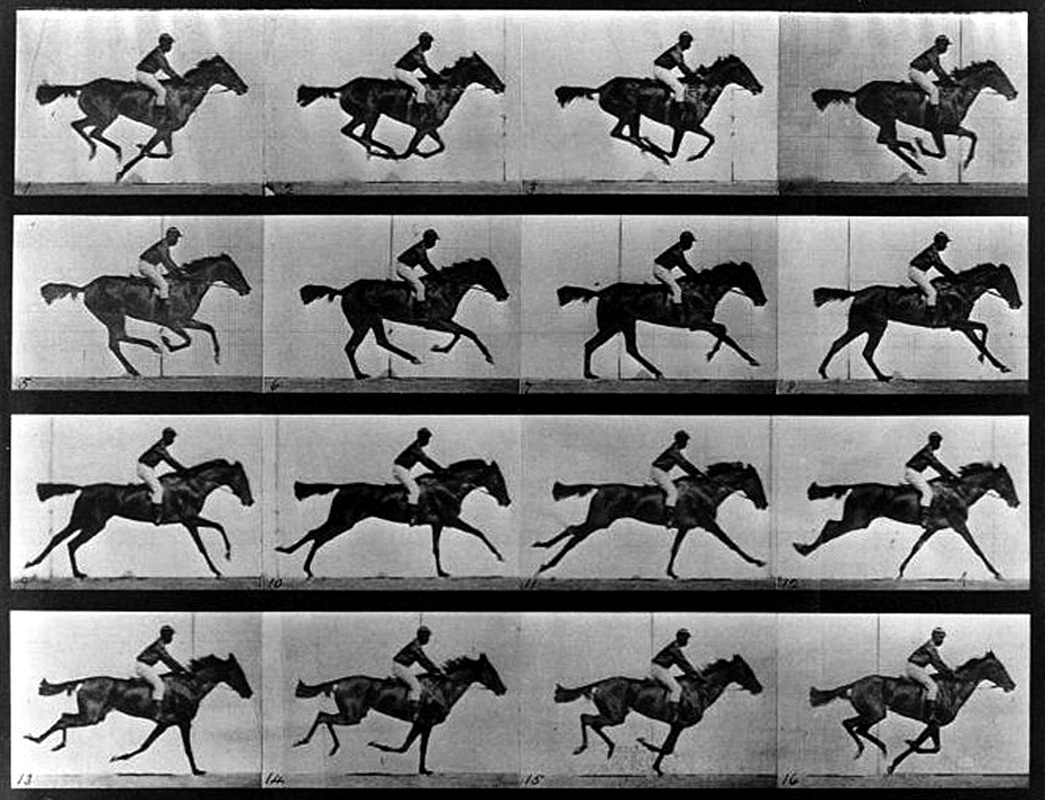

The ability of photographs to show us what we cannot otherwise see has long fascinated scientists and artists. Our sense of time is duly warped by photographs like these. Early pioneers like Eadweard Muybridge and Étienne Jules Marey invented a range of methods for capturing photographs of nature previously inaccessible to human vision. Muybridge famously proved that a horse could fly (if only temporarily), whereas Marey invented a kind of camera gun capable of recording 12 photographic frames per second, capturing movement in a single image.

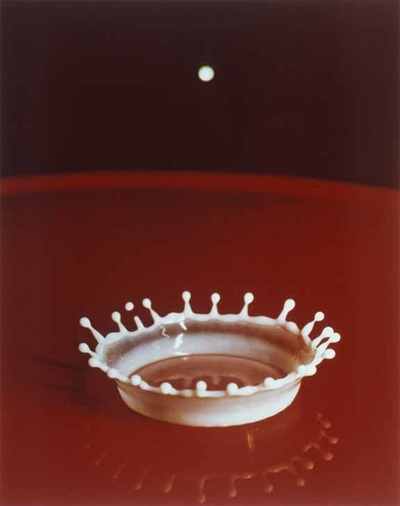

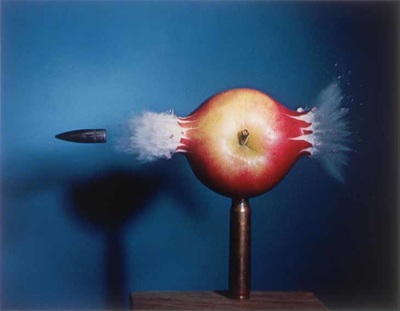

As photographic technology became more sophisticated and scientists developed ever more startling theories about time, further experiments could take place. These famous images by Harold "Doc" Edgerton use ultra high speed flash guns to stop fast moving objects invisible to the naked eye. Edgerton was an engineer. Photography enabled him to visualise the laws of physics in a way that captivated the viewer. Time is a mystery. Stopping it allows us to see its invisible workings.

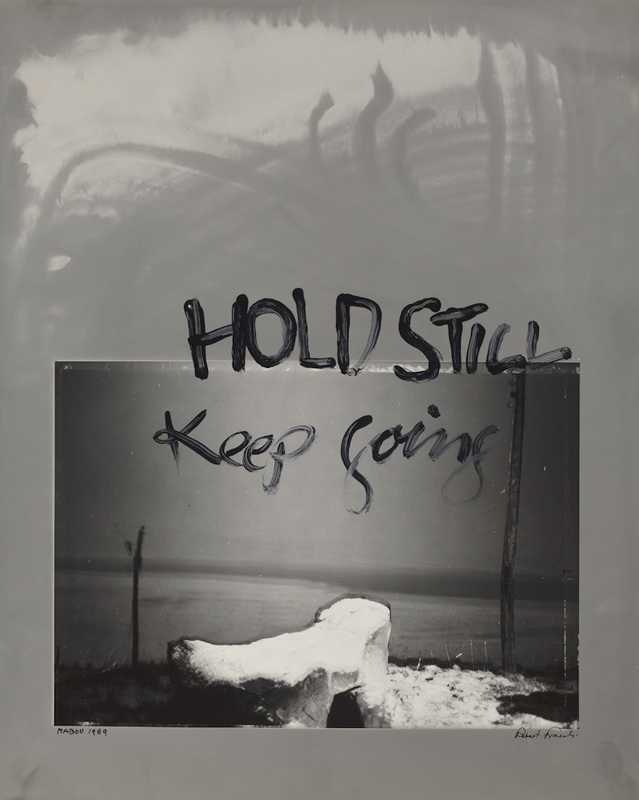

Still going

|

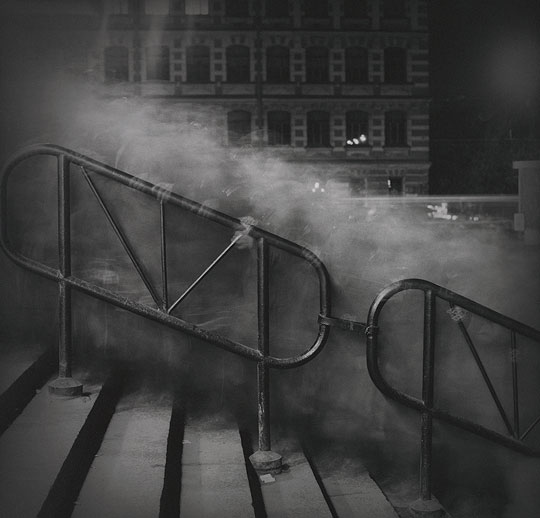

Rather than using fast shutter speeds to stop time, what happens when you choose to leave the shutter open? Depending on the ambient light levels you may need to use a neutral density filter. A tripod might also come in handy. Here are some examples of photographs that exploit the camera's ability to capture the passage of time.

|

Light left on the screen

|

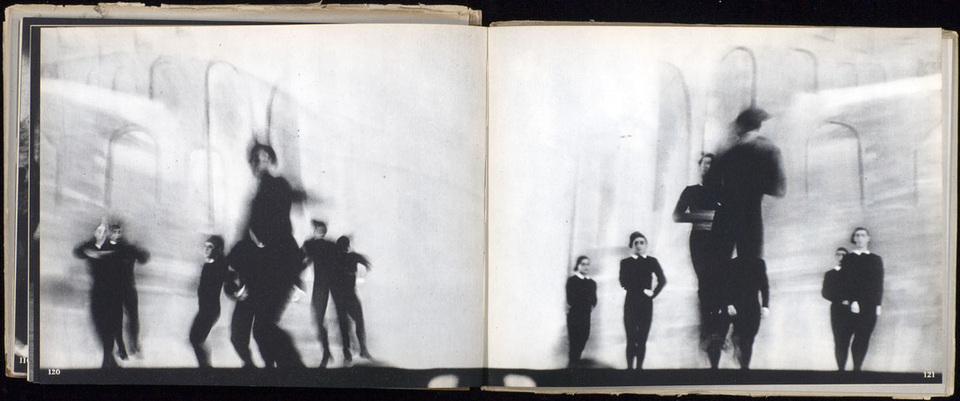

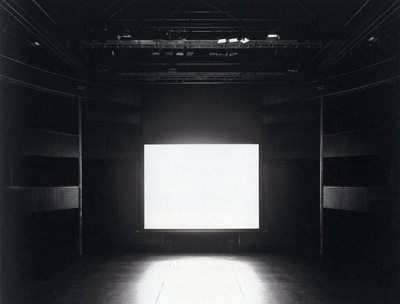

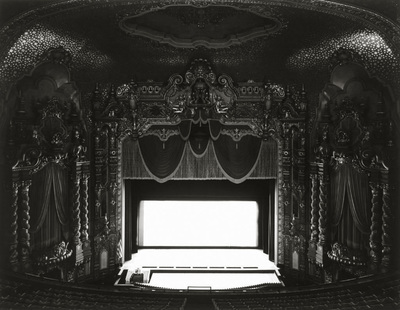

There is a great deal written about the relationship between photography and film. Lens and Light Based Media courses often encourage students to consider making work that utilises both still and moving images. Many photographers create film and/or video work alongside still photographs. Some photographs, however, stretch the definition of still photography almost to breaking point. These are images that result from leaving the shutter open for unusually long periods. Consider these photographs by Horishi Sugimoto:

|

I open the shutter when the movie begins, when the title shows up. Then I just leave the camera open for two, three hours - whatever the length of the movie is. When the ending credit shows up, I just close the shutter. So I photograph the entire movie images. When I process the film no images from the movie show, just showing a white light left on the screen. Interiors of the theatres show, reflecting the white light coming out from the screen. The people who were in the theatre all disappear receiving this radiant white light from the screen. How do you show the nothingness, emptiness? You have to have something surrounding the nothingness. In this case, the movie theatre is the “case” that holds this emptiness.

-- Hiroshi Sugimoto

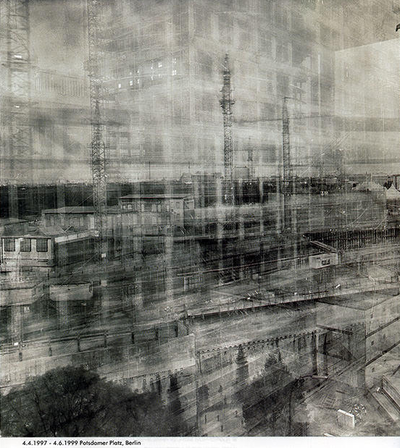

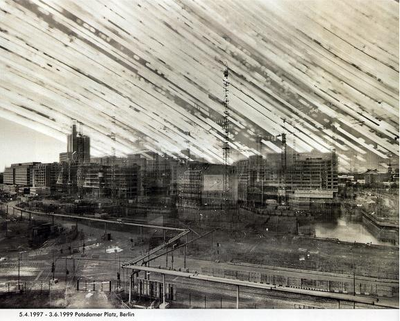

Photographer MIchael Wesely adapts his large format camera so that it is capable of incredibly long exposures. He has claimed that, in theory, he could create a photograph with a shutter 'speed' of 40 years! He recently documented the four year re-construction of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. His images of the re-construction of Leipziger and Potsdamer Platz in Berlin often feature trails of light in the sky, the path of the sun. Solargraphy is the name given to the art of capturing these sun trails. These images have the durational quality of films contained within the formal constraints of the still photograph.

Suggested activities:

- Experiment with photographing moving objects using a range of shutter speeds. What happens if you attempt to use extremely long shutter speeds - the length of an entire film, for example?

- In a dark room, explore the range of effects that can be achieved with long shutter speeds, various light sources and a flash gun. If available (try your science department) experiment with stroboscopic light and long exposures.

- Create a solargraph, tracking the path of the sun over several weeks/months.

Stop all the clocks

|

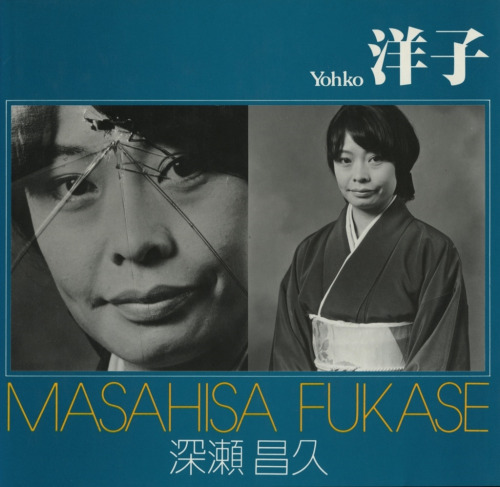

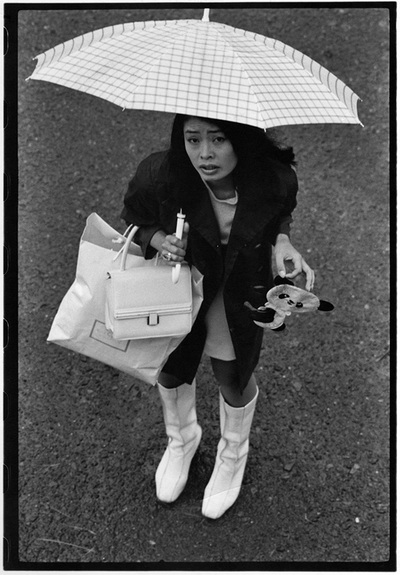

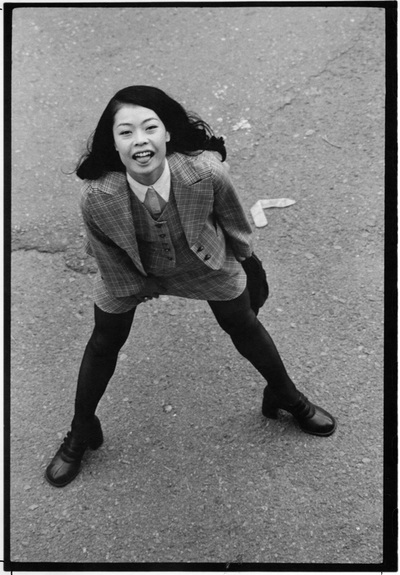

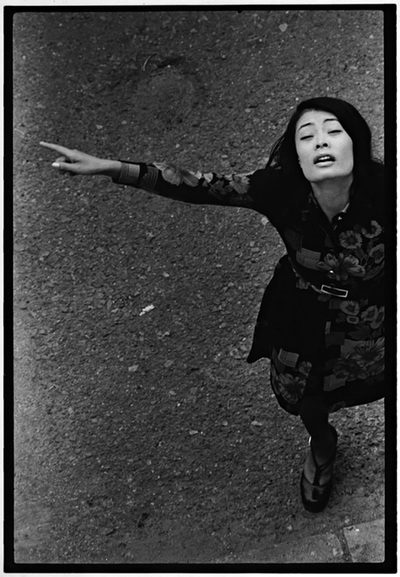

For some photographers, the camera has been used to document daily rituals, thereby attempting to catalogue and interrogate the flow of time. In the case of the Japanese photographer Masahisa Fukase, this process became an obsessive (and ultimately tragic) habit. In the series From Window, Fukase photographs his wife Yoko leaving for work every morning in a different outfit. This daily performance reflects just part of Fukase's 13 year project devoted solely to photographing his wife.

I work and photograph while hoping to stop everything [...] In that sense, my work may be some kind of revenge drama about living now. |

Fukase's need to control time (and Yoko herself) resulting in her leaving him in 1976. Deeply depressed, Fukase turned his attention to ravens, themselves symbolic of mortality. He fell down the stairs of his favourite club in 1992, spending 20 years in a coma before dying in 2012. Yoko visited him twice a month throughout his 20 years in limbo.

The repetitive nature of Fukase's photographing is reflected in this scene from the film Smoke, scripted by the American novelist Paul Auster.

The repetitive nature of Fukase's photographing is reflected in this scene from the film Smoke, scripted by the American novelist Paul Auster.

|

|

Auggie owns a tobacconists in Brooklyn. It's the centre of his world and every morning he photographs it from across the street. A regular customer called Paul sees his photograph albums. Flicking quickly through them Paul thinks the photos all look the same. Auggie tells him, "You'll never get it if you don't slow down my friend." Auggie advises Paul to pay more attention to the passing of time before quoting the famous soliloquy about time from Macbeth. Auggie explains, "the Earth revolves around the sun and every day the light from the sun hits the Earth at a different angle." Paul sees someone he knows in one of the photos: his wife Ellen, who was killed one morning on the street outside the store. Grief stricken he begins to cry. The photographs no longer look the same.

|

|

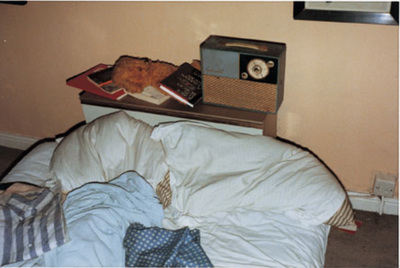

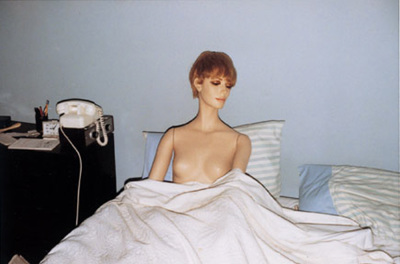

An interesting variation on this approach to repetitive doucumentation can be found in Stephen Shore's project American Surfaces. On a road trip across the States in the 1970s, Shore developed a ritualised process of photographing repetitive elements of the journey - every toilet he used, every meal he ate, every bed he slept in etc. The resulting images of the entire trip, taken with a Rollei 35, were simply displayed as 6x4 prints, the repetitive elements creating a kind of vocabulary of forms.

I didn’t think about beauty a lot. I saw myself as an explorer. |

The meals |

The beds |

Shore is not interested in Cartier-Bresson's decisive moment but in the mundane, unremarkable and routine, when the culture of a place reveals itself. Neither is he interested in the memorialising quality of photography. Shore is an avid user of Instagram and creates self-published photobooks but you would struggle to learn much about his personal life from these images, whereas you might develop an intimate understanding of the texture and colour of the ground beneath his feet.

Suggested activities:

- Photograph the same daily ritual over several days/weeks. Examples might include: eating, teeth brushing, getting dressed, waiting at the bus stop etc.

- Choose one or more of your favourite photographs. Bury them in the garden. After a few days/weeks, dig them back up. How have they been transformed?

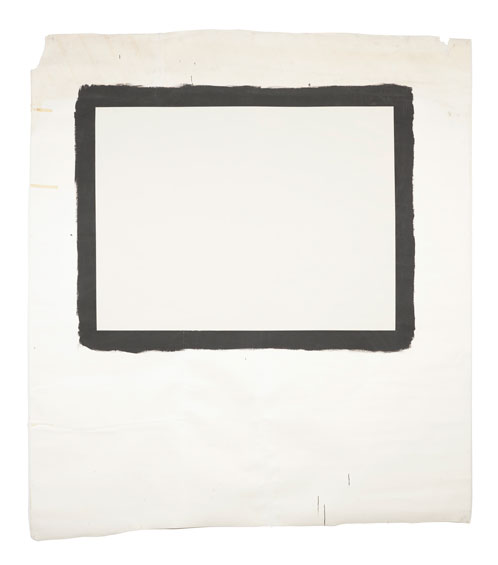

Less is more (more or less)Tony Conrad is an artist who has consistently questioned our relationship to time through his experimental work in a variety of mediums. Take a look at the image on the right entitled 'Yellow Movie 2/28/73'. Make a quick list of what you can see. What expectations are you given by the title? How are these frustrated?

In the video below, Conrad explains the nature of this piece, its challenge to the notion of duration in an art work and its relationship to both photography and film. Essentially, the work represents an attempt to create a 'film' that could last 50 years. In other words, it won't be finished until at least 2023. After that, who knows? |

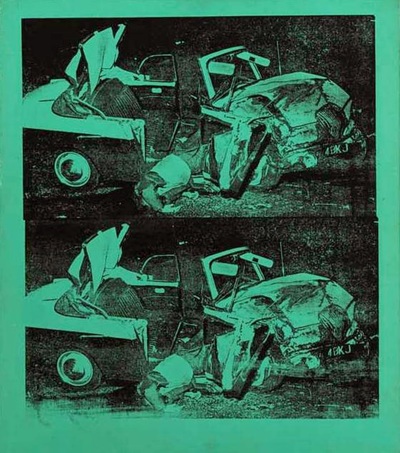

Images of Generation Anthropocene

In this great article, author Robert Macfarlane outlines the language now being used to describe the catastrophic impact humans have had on the geology of Planet Earth. The Anthropocene is proposed as the term best suited to "the new epoch of geological time in which human activity is considered such a powerful influence on the environment, climate and ecology of the planet that it will leave a long-term signature in the strata record." Interestingly, the word was added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2014-15, the same year as "selfie". Discussions are taking place about the official start date of the Anthropocene ought to be. The middle of the 20th century looks likely to be the official outcome. Along with nuclear energy, plastics and the mass extinction of wild species, the era is characterised by the adoption of photography as a mass, democratic art form. As Macfarlane notes:

Anthropocene art is, unsurprisingly, obsessed with loss and disappearance.

In the first exhibition of its kind, the Deutsches Museum in Munich has created an Anthropocene cabinet of curiosities, the central themes being urbanisation, mobility, humans and machines, nature, food and evolution. In each case, photography has proved to be the perfect art form for capturing Generation Anthopocene.

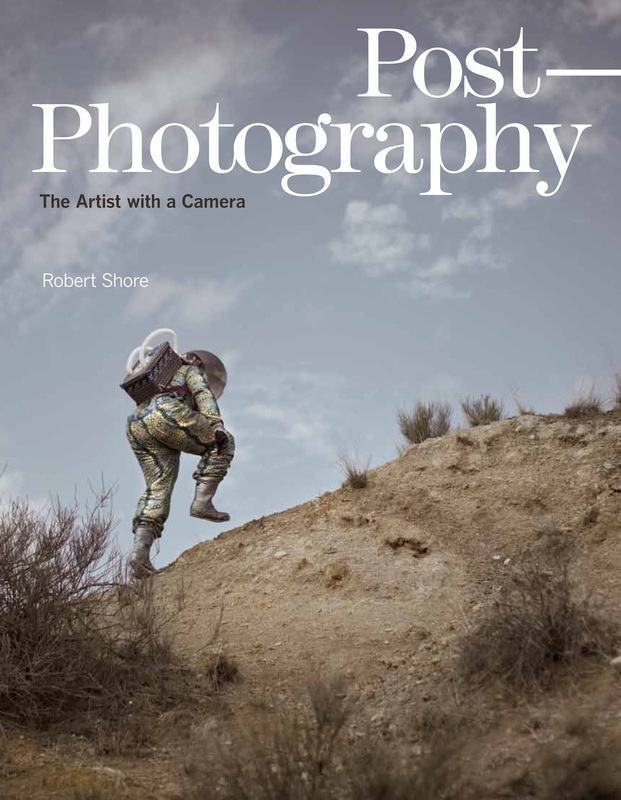

Photography is dead; long live 'photography'Perhaps the greatest irony about photography's relationship to time is that many commentators are now speaking about the age of post photography. In other words, the digital revolution has resulted in the demise of analogue or film based photographic practice. At best, chemical photography is now an antiquarian pursuit, belonging to the history of photography rather than its future. The switch from chemical to digital practices has had other effects however which we are only just beginning to recognise. There has been a break with the direct (indexical) connection with the light source. A digital image is computational. Light is registered as data. The resulting 'photograph' is created by software, reading the data and turning it into what looks like a photograph. But the process is very different to that of analogue cameras carrying light-sensitive material. There is a pervading nostalgia for film, especially amongst young people, perhaps because they have grown up with digital and are searching for something more authentic. Every digital photo reminds us that we have 'lost' photography.

Photography is certainly not dead but it has radically changed. Our relationship to photographic images has also undergone a dramatic transformation. We are now living in a post-modern, post-industrial, post-photographic age. Digital photographs continue to warp our sense of time but in new ways. Many mourn the loss of the old ways and cling to the chemical life raft as its slips into the distance. Meanwhile, today's photography students are exploring new territories, their eyes on the horizon, occasionally glancing backwards to get their bearings. |

We owe it to the medium that we’ve nurtured into adolescence to stand by it and support it in adulthood even though it might seem unrecognisable in its new form. We know the alternative: it will be out the door and hanging with the wrong crowd while we sit forlornly in the empty nest wondering what we did wrong. The first step is to stop talking about the child it once was and to put away the sentimental memories of photography as we knew it for all these years. It’s very far from dead but it’s definitely left the building.

-- Stephen Mayes

Suggested activities:

- Speculate on the future of photography? How will students study photography in 10, 20, 30 years?

- How has the invention of digital photography changed the nature of photographic images? Is a photographic image any more or less 'true' than it used to be when film was the dominant medium for photographs? What have we gained from digital technologies? What have we lost?

- Create a series of photographs (perhaps experimenting with a mixture of digital and analogue technologies) that explore your feelings about the future of photography...

Further reading:

The following books and resources might prove useful in researching some of the issues raised by TC#10:

Moments in Time

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

|

This booklet, produced by Tate to support the interrogation of lens and light-based media in its collection, contains very useful prompts about the nature of photography's relationship to time. These include:

* my additions in italics

|

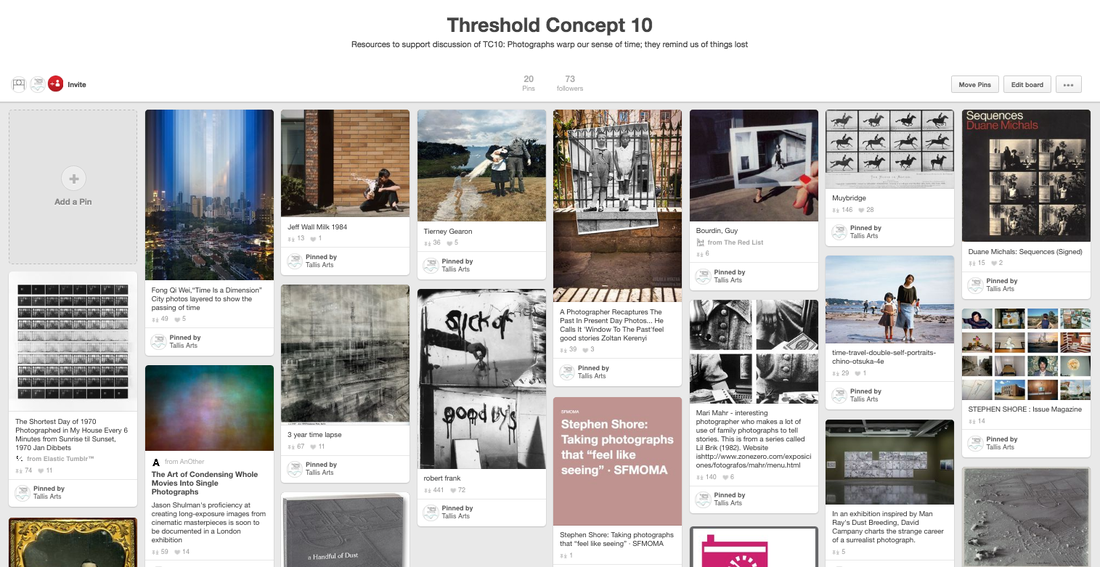

TC#10 on PinterestA range of resources to support the ideas in Threshold Concept #10 can also be found on Pinterest.

|

By Jon Nicholls