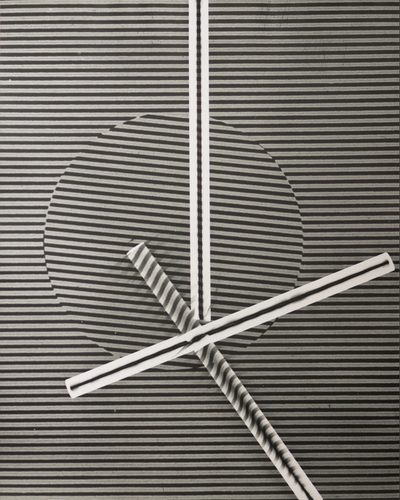

The capturing of light...

|

|

Romain Alary and Antoine Levi, photographers and cinematographers, demonstrate in this short film the way that light behaves in a camera obscura. A room is made completely dark except for a small hole which allows light to stream in. Light travels in straight lines (OK, I'm no physicist but bear with me) which means that the light bouncing off the tops of buildings or trees ends up projected on an interior wall upside down. Images inside a camera obscura (like in our eyes before the brain takes over or in some old cameras) are upside down. |

The relationship between art and the representation of reality is a long and complicated story. Hand prints have been found in caves that date back 28,000 years. Devices like the camera obscura, the pantograph and the Physionotrace have been used by artists to create more believable or accurate renderings of various visual phenomena. A means to capture and fix the light from the real world became the Holy Grail for entrepreneurs, inventors and scientists.

Suggested activities:

- Have a go at making your own camera obscura. This is very straightforward and helps to explain the way that light works in a very accessible and illuminating (pun intended) way. If you have the time (and a suitable space) it's fantastic to turn your teaching room into a camera obscura. I did this once during one of those activity days in school. We spent the morning taping large sheets of heavy black plastic sheeting across the strip of windows in a Modern Foreign Languages room. When we cut the small hole in the centre, a bright stream of light entered. It took about five minutes for our eyes to adjust to the light and then we spent the rest of the day lying on the floor watching people walking across the ceiling. Magic.

- Don't forget to research the work of Abelardo Morell who makes fantastic use of the process to create a whole series of wonderful room-shaped cameras.

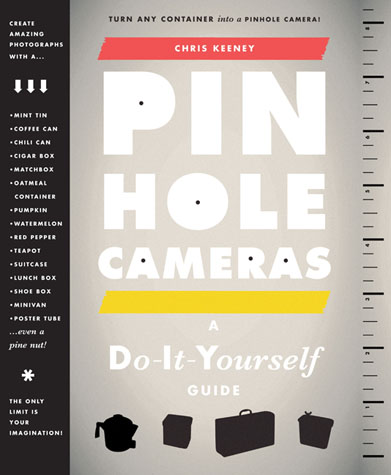

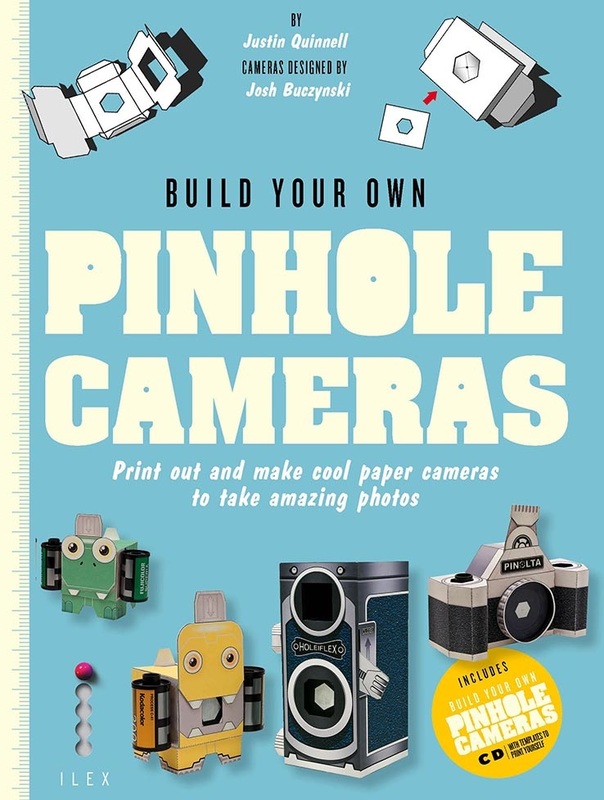

- The next step on from camera obscura is making your own pinhole cameras. The whole process of creating a simple camera from scratch is a fantastic introduction to the subject for younger students (and older ones too). There are loads of great How To instructions and videos online and great texts on the market, including books that transform themselves into pinhole cameras.

- Research the work of artist Steven Pippin, whose fascination with photographic technology includes creating pinhole cameras from washing machines, a photobooth and a bath tub.

Photographic Firsts

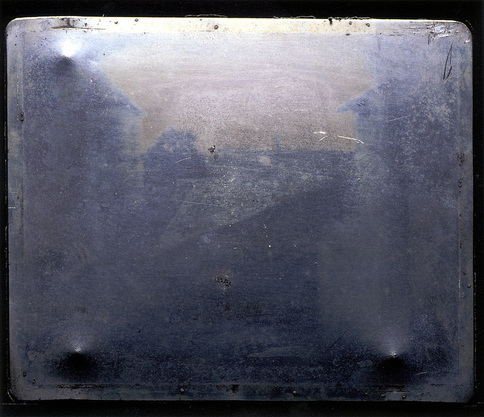

Debates about the origins of photography have raged since the first half of the nineteenth century. The image above left is partly the reason. View from the Window at Le Gras is a heliographic image and arguably the oldest surviving photograph made with a camera. It was created by Nicéphore Niépce in 1826 or 1827 at Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, France. The picture on the right is an enhanced version of the original which shows a view across some rooftops. It is difficult to tell the time of day, the weather or the season. This is because the exposure time for the photograph was over eight hours.

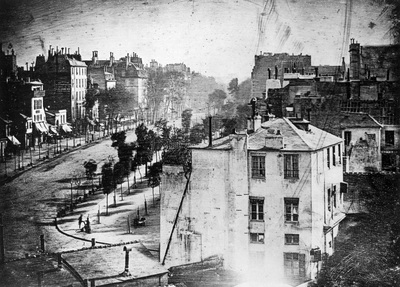

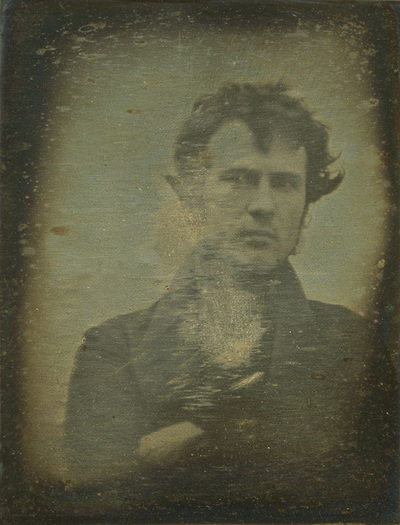

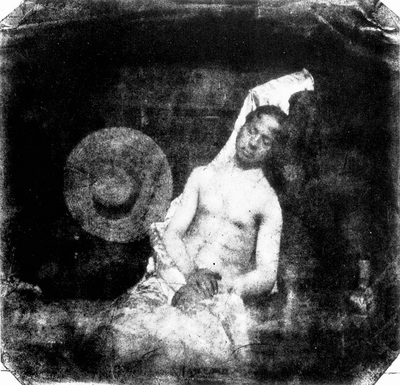

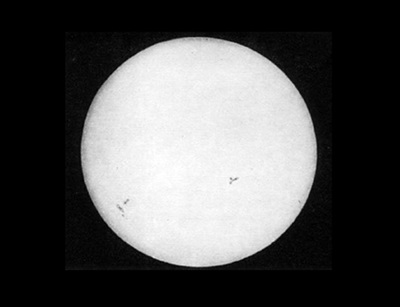

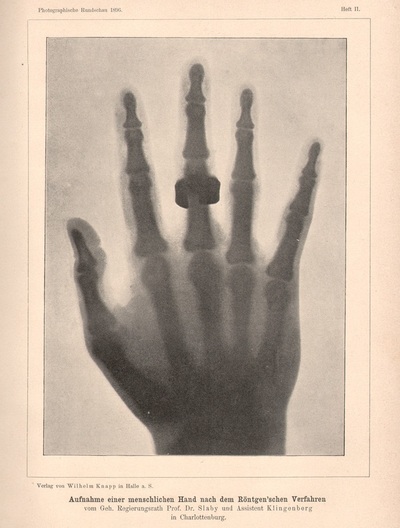

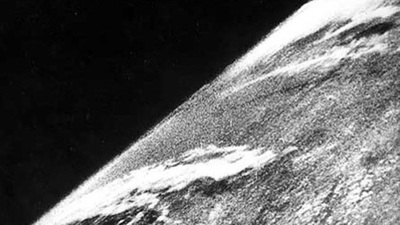

Here are eight other photographic firsts. Click on the images links to find out more about them. Other than being pioneering examples of their kind, what else do they have in common?

Here are eight other photographic firsts. Click on the images links to find out more about them. Other than being pioneering examples of their kind, what else do they have in common?

The early days

|

This article and the link to the video opposite do a great job of explaining the intense sequence of events in the development of early photographic processes.

Photographers in the 19th century were pioneers in a new artistic endeavor, blurring the lines between art and technology. Frequently using traditional methods of composition and marrying these with innovative techniques, photographers created a new vision of the material world. |

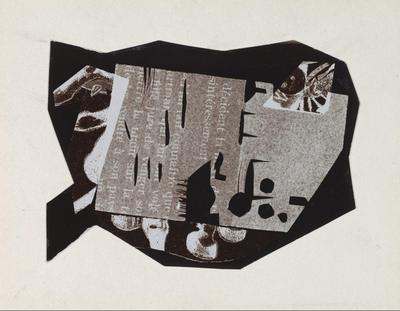

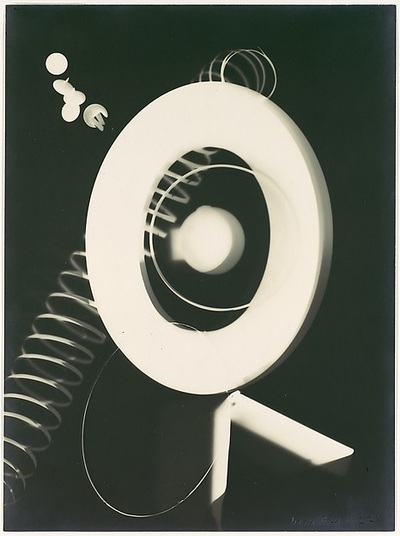

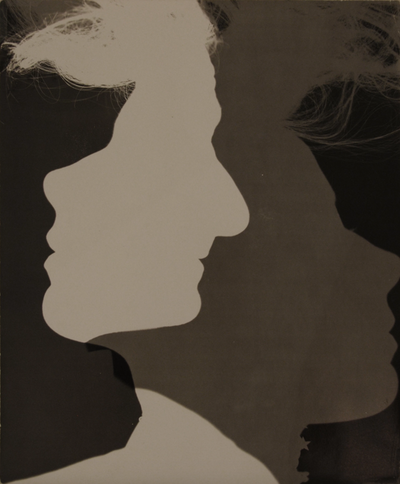

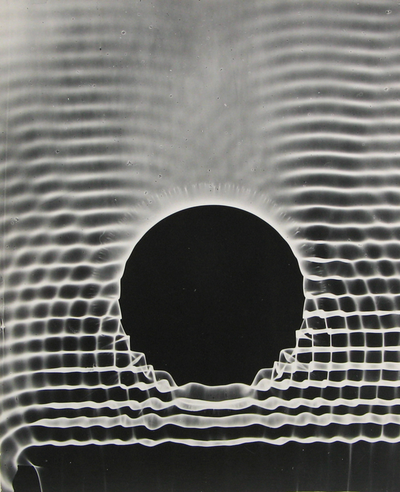

All photography is the capturing of light and includes images that are made without a camera or film.

|

Shadow Catchers: Camera-less Photography from the V&A

|

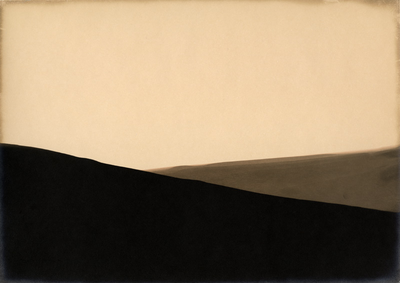

The invention of photography, however, is not synonymous with the invention of the camera. Cameraless images were also an important part of the story. William Henry Fox Talbot patented his Photogenic Drawing process in the same year that Louis Daguerre announced the invention of his own photographic method which he named after himself. Anna Atkins' British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions of 1843 is the first use of photographic images to illustrate a book. This method of tracing the shapes of objects with light on photosensitive surfaces has, from the very early days, been part of the repertoire of the photographer. The directness and immediacy of making photograms (as they are most commonly known) has provided generations of photographers with opportunities to experiment with light and materials.

|

A window on photography |

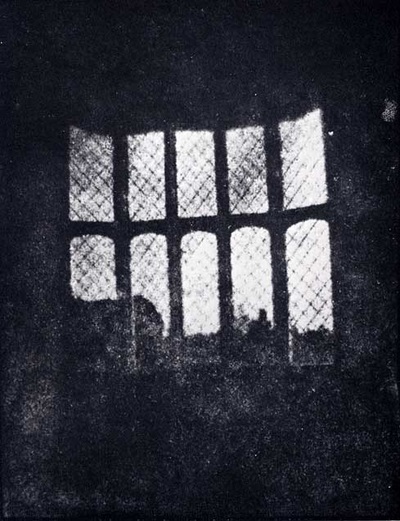

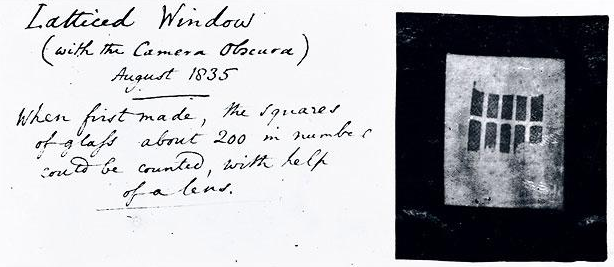

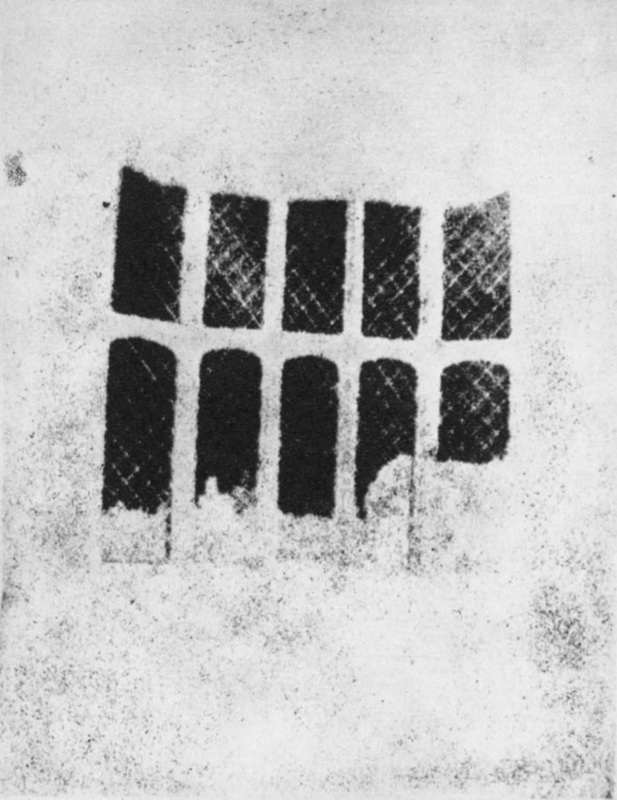

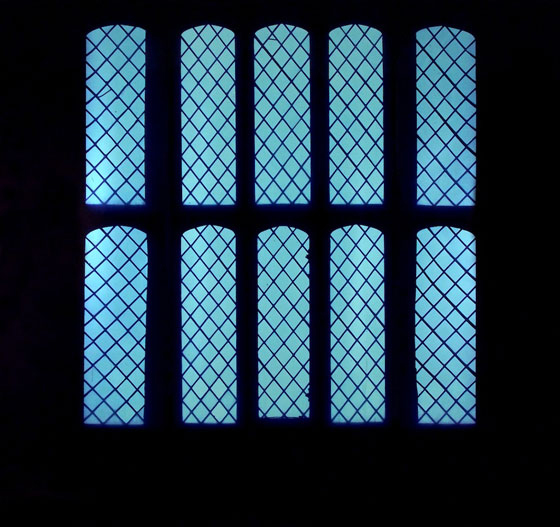

Do you remember the picture of a large bay window, the first paper negative ever to be made? In the summer of 1835 William Henry Fox Talbot experimented with various chemicals to develop paper coatings suitable for use in a camera. He placed small wooden cameras that his wife called "mousetraps" all over his estate. The earliest surviving paper negative dates from August 1835, a small recording of the bay window of Lacock Abbey (left). In 1978, the German photographer Floris Neusüss visited Lacock Abbey to make photograms of the same window. He returned again in 2010 for the Shadow Catchers exhibition at the V&A to create a life-sized version of Talbot's window (below right). |

That 1978 photogram was the start of our adventures in creating photograms of large objects in the places where we found them [...] we took our equipment to Lacock Abbey and made a photogram of a fixed subject. This particular subject was for us not just a window in a building but an iconic window, a window on photography, opened by Talbot. The window is doubly important, because to be able to invent the photograph, Talbot first used photograms to test the light sensitivity of chemicals. His discovery became a window on the world. I wonder what percentage of our understanding of the planet we live on now comes from photographs?

-- Floris Neusüss

The idea of photographs functioning like windows makes total sense. Like the camera viewfinder, windows frame our view of the world. We see through them and light enters the window so that we can see beyond. Photographs present us with a view of something. However, it might also be possible to think of photographs as mirrors, reflecting our particular view of the world, one we have shaped with our personalities, our subconscious motivations, so that it represents how our minds work as well as our eyes. The photograph's glossy surface reflects as much as it frames. Of course, some photographs might be both mirrors and windows. If you're interested in thinking a bit more about this you might want to check out this resource.

Suggested activities:

|

Noticing the lightTake a close look at these images. What do they have in common? They are all, in one way or another, documentary pictures of vehicles, each commenting on the American Dream. Instead of analysing them according to genre, subject matter or theme, however, try the following:

|

Index or trace?

There are many theories of photography, ways of interpreting the meaning of photographs. When we say that it is important to be visually literate (or media literate or even photo literate) we mean that it is useful, in a world that is saturated by visual media, to have some tools with which to interrogate images of various sorts. When it comes to the essence of photographic images, the direct relationship between the photograph and the object photographed is reliant on the light that passes from one to the other. This is sometimes called an "indexical" relationship. The word comes from the American philosopher Charles Sanders Pierce whose work on semiotics (a way of understanding how communication works) was first published in the 1930s. He identified three types of sign: indexical, iconic and symbolic. He referred to photographs as examples of indexical signs because of their direct physical relationship to the thing photographed.

The camera does more than just see the world; it is also touched by the world. Light bounces off an object or a body and into the camera, activating a light-sensitive [surface] and creating an image. Photographs are therefore designated as indexical signs, images produced as a consequence of being directly affected by the objects to which they refer. It is as if those objects reached out and impressed themselves on the physical surface of the photograph, leaving their visual imprint...

-- Geoffrey Batchen

Of course, not all photographs represent objects as they look to our eyes. Writers like Susan Sontag and André Bazin recognise that, despite various kinds of distortion (out of focus, discoloured etc.) all photographs offer a kind of proof that something happened. Other writers prefer the word "trace" to describe how photographs work. Alan Trachtenberg, for example, uses the example of a shadow and a footstep as an analogy for photographs. A shadow is an indexical sign, directly related to the object and the light. A footstep, however, is an "iconic" sign that resembles its object but does not have a material connection to it. It is the trace of a human presence having left a mark on the land. A drawing of a person has a similar relationship. It is also a trace.

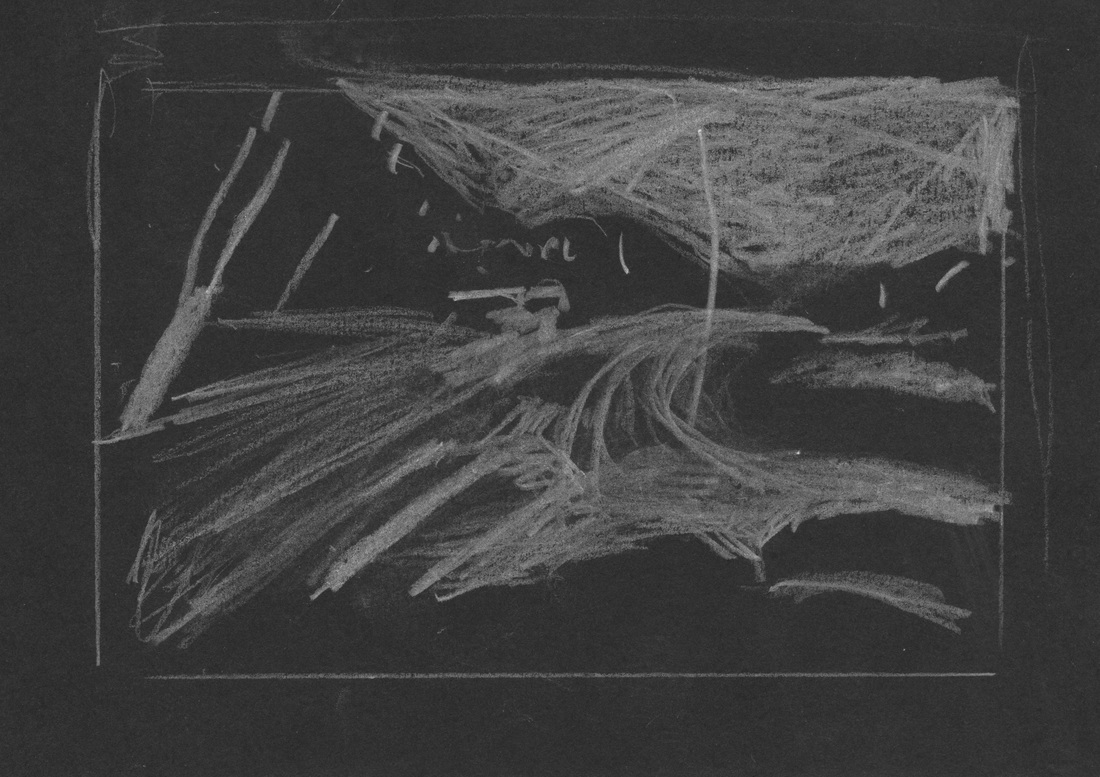

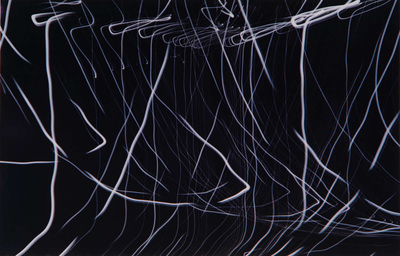

Take a look at these photographs. Think about them in terms of the directness of their relationship to the things photographed. How do these images capture light and how does this affect our relationship to them?

Take a look at these photographs. Think about them in terms of the directness of their relationship to the things photographed. How do these images capture light and how does this affect our relationship to them?

What is a photograph?

This question cuts to the heart of the matter. There have been numerous attempts to define photography once and for all but these have inevitably either neglected peculiar examples or been superseded by developments in practice. Perhaps it's only possible to assert that the one common denominator of all photographs is that they rely on radiant energy (light, x-rays, gamma rays or cosmic rays) for their existence. As we have seen, a camera is most definitely optional. Much more than this is difficult to to say.

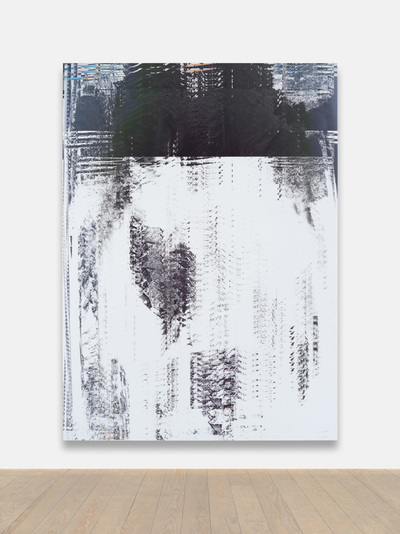

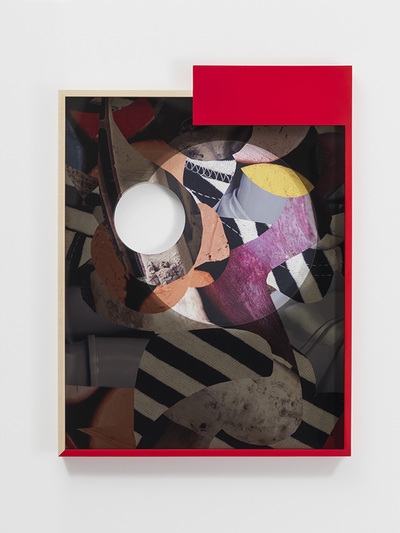

In 2014, the International Centre for Photography in New York held an exhibition with the title 'What is a Photograph?'. The exhibition explored experimental photography since the 1970s, including artists who have "reconsidered and reinvented the role of light, colour, composition, materiality, and the subject in the art of photography". These experiments are, in part, a response to the digital revolution and the role that digital technology now plays in photography. This has prompted a renewed interest in analogue photography and the hybrid creations generated when analogue and digital collide. Criticism of the show drew attention to backward-looking, fine arty-ness and abstraction of the images on display.

In 2014, the International Centre for Photography in New York held an exhibition with the title 'What is a Photograph?'. The exhibition explored experimental photography since the 1970s, including artists who have "reconsidered and reinvented the role of light, colour, composition, materiality, and the subject in the art of photography". These experiments are, in part, a response to the digital revolution and the role that digital technology now plays in photography. This has prompted a renewed interest in analogue photography and the hybrid creations generated when analogue and digital collide. Criticism of the show drew attention to backward-looking, fine arty-ness and abstraction of the images on display.

The show doesn’t answer the question [What is a photograph?]. Rather, it brings together works from the past four decades by 21 artists who have used photography to ponder photography, leaving viewers to figure it out for themselves [...] Several artists are committed to the processes and materials of the nearly obsolete darkroom [...] It’s a strangely blinkered and backward-looking show. Nearly all the work on view has more to do with photography’s past than with its possible future.

-- Ken Johnson

Take a look at some of the work featured in the show. Follow the links to find out more about the artists/photographers. What do you think?

Writer Jacob King is also troubled by this kind of photography exhibition in which photographs are displayed as works of art, like paintings or sculptures:

the gap between the photographic “objects” on view here and the myriad ways that photographs exist and circulate today is almost comical. While the exhibition included a number of interesting works, a viewer could walk through the show without ever knowing that a photograph could be viewed on a cell phone, that it could exist as a digital file, that it could circulate on the internet, that it could be tagged, or even that it could frame and reproduce something which was once before the camera’s lens (let alone that it might exist in an application like Snapchat.)

Photography finds itself at a crossroads. As analogue processes become obsolete and photography culture becomes ever more digital, photographs themselves are becoming increasingly dematerialised and more technologically sophisticated. Digital photographs are computational images and their relationship to reality is more complex than that of photogram or black and white film negative. Photographs in the future may look very different to those of today. They may include much more information than simply the activity of radiant energy.

The revolutionary change in photography’s cultural presence wasn’t led by photographers, nor publishers or camera manufacturers but by telephone engineers, and this process will repeat as business grasps the opportunities offered by new technology to use visual imagery in extraordinary new ways, throwing us into new and wild territory. It’s happening already and we’ll see the impact again and again as new apps, products and services hit the market. We owe it to the medium that we’ve nurtured into adolescence to stand by it and support it in adulthood even though it might seem unrecognisable in its new form. We know the alternative: it will be out the door and hanging with the wrong crowd while we sit forlornly in the empty nest wondering what we did wrong. The first step is to stop talking about the child it once was and to put away the sentimental memories of photography as we knew it for all these years. It’s very far from dead but it’s definitely left the building.

-- Stephen Mayes

|

|

Pushing the boundariesIn this fascinating video, artist Marco Breuer reflects on the unique qualities of photographic paper and the possibilities that this material can offer. Breuer highlights that while photographic paper is usually labelled 'light-sensitive' it also remains sensitive to other forms of manipulation.

|

Some questions to consider:

- How do you use photographs in your everyday life?

- Do you see any connection between everyday photography and the subject you study for A level?

- What do you think photographs will be like in 30 years time?

- What will photographs enable us to 'see' in the future?

- Will photographs in the future continue to be physical objects?

- Will people still be using cameras as we now know them?

- Will we still need categories like art, photography or film in the future?

By Jon Nicholls