The view from here...

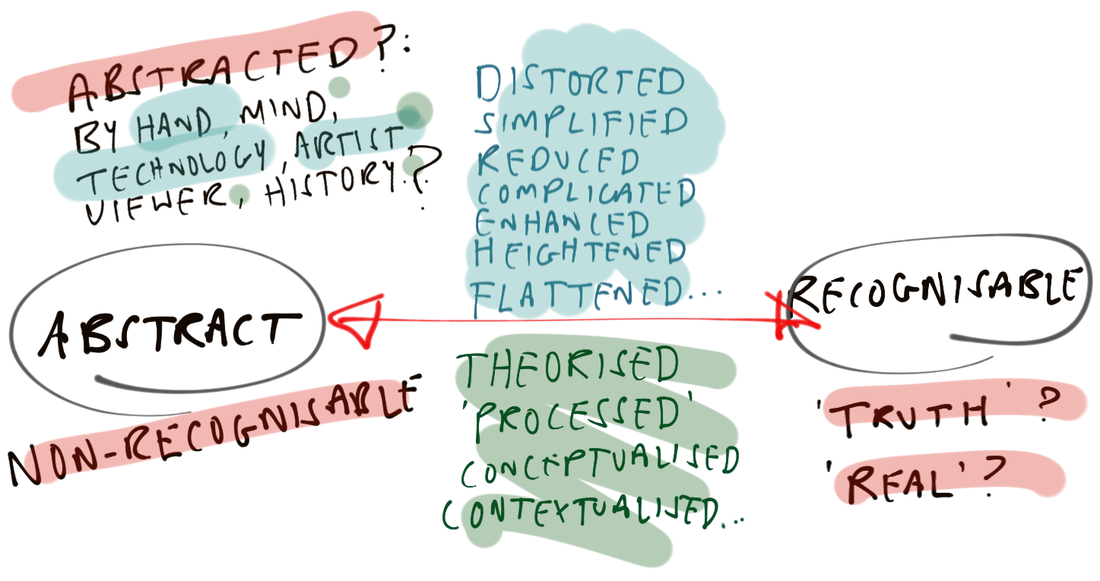

All photographs are, to some extent abstractions. Whether you agree with this will be largely dependent on your understanding of - or definition for - the term abstraction, which in itself is quite ambiguous.

ABSTRACTION

- Dealing with ideas rather than events

- Freedom from representational qualities (in art)

- The process of considering something independently of its associations or attributes

- The process of removing something

Anyhow, here's a few statements to kick about with a class beginning to question photographs as abstractions:

Would you disagree with any of the following?

- Photographs are illusions

- Photographs are flat

- Photographs are not real

- Photographs are surreal

- Photographs are made up of...dots, tones, textures, shapes, colours...visual (or formal) elements.

Windows to abstraction

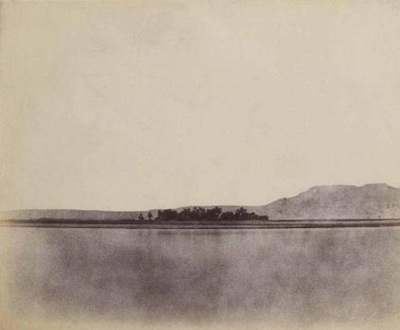

The heliograph above, captured by Joseph Niépce, c. 1826, is widely considered as one of the first photographs. It presents a view from his window, exposed for about eight hours while the sun changed position. The subject matter is easily enough recognised (and if not the title 'View from the Window at Gras' is quick to join the dots), but yet the image is far from realistic or representational. For those with a basic grounding in art history - and viewing from our contemporary perspective - it is only a short leap to consider this in more abstract terms, as a combination of tones, textures and shapes upon a surface. But yet any potential abstraction here is borne of the technology of the time rather than a deliberate intention of Niépce, the image-maker.

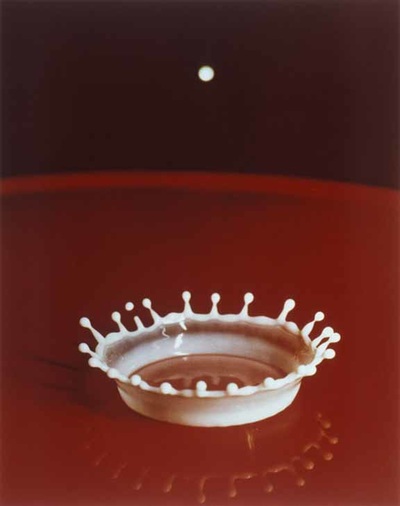

Since 1826, camera technologies have evolved in ways that Niépce would never have imagined and, at least on the surface (a perfect expression for photography discourse), the journey appears one of increasing 'accuracy', notably with the arrival of colour imagery via Thomas Sutton in 1861. However, technological advances - for example the ability to capture microscopic detail, or the blurred (or fixed) movement of a speeding...well, anything e.g. horse, bullet, car - have also led to alternative ways of recording. And seeing. Arguably, these images, such as Harold Edgerton's 'Crown Coronet' or Von Ettingshausen's 'Section of a Clematis' (below), are as abstracted as they are heightened in their own elaborations on reality.

Since 1826, camera technologies have evolved in ways that Niépce would never have imagined and, at least on the surface (a perfect expression for photography discourse), the journey appears one of increasing 'accuracy', notably with the arrival of colour imagery via Thomas Sutton in 1861. However, technological advances - for example the ability to capture microscopic detail, or the blurred (or fixed) movement of a speeding...well, anything e.g. horse, bullet, car - have also led to alternative ways of recording. And seeing. Arguably, these images, such as Harold Edgerton's 'Crown Coronet' or Von Ettingshausen's 'Section of a Clematis' (below), are as abstracted as they are heightened in their own elaborations on reality.

Suggested activity:

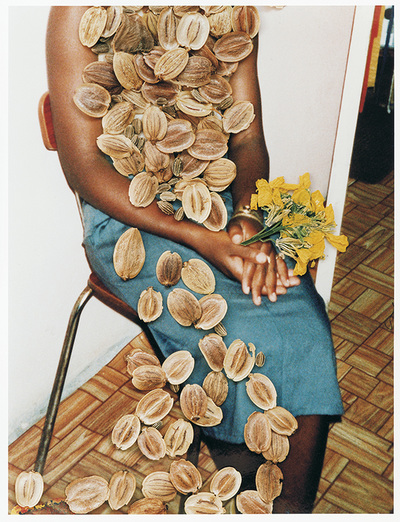

The five images below (and subsequent links) provide examples for discussion that, in one way or another, might demonstrate photographers taking a step away from what might be percieved as 'real'.

|

The word 'RECOGNISABLE' is not a perfect fit - something might be recognisable as abstract; shape, colours etc. are recognisable, and so on. - but for this introductory exercise it still seems the most accessible term. REPRESENTATIONAL or IDENTIFIABLE might be alternatives, but they are not without their own baggage.

|

|

In his staged photograph 'Self-portrait as a Drowned Man' (1840) Hippolyte Bayanard is pretending to be dead. How does the fact he is (now) actually dead change the truth of the image? |

Is the mountain still in the distance in the photograph 'The Banks of the Nile at Thebes' (1854) by John B. Greene? How can this be when the photograph is flat? Is this an illusion of distance, or a presumption that we make based on our experiences? |

Art, Photography and AbstractionIt is difficult to unpick the abstract nature of photography without considering its development alongside that of modern and contemporary art. Since the turn of the 20th Century - when the Photo-Secessionists laid claim to photography as a fine art form - the roots of art and photography have become deeply entwined. This shared evolution, from pictorial concerns to abstraction (and beyond), makes for a fascinating tale. In many ways it is the story of our time, reflective of a rapidly changing world at war and unprecedented advances in technologies (transportation, manufacturing, print and moving image to name a few). It's an essential timeline to unravel with students if they wish to gain a deeper contextual understanding of abstraction.

Suggested activities:

|

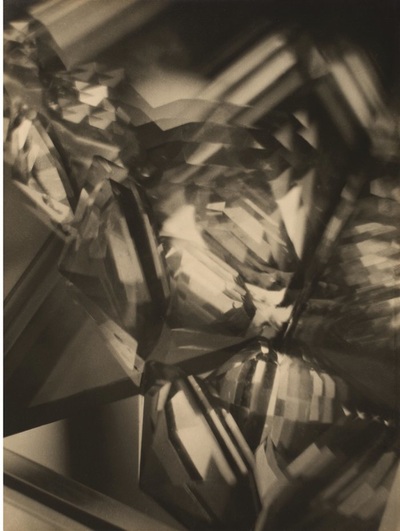

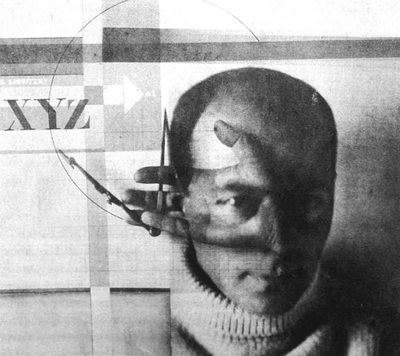

The images above were created by photographers early in the 20th Century borrowing heavily from the visual languages of the time, including Cubism, Futurism and Constructivism.

|

- Look at the four examples of photographs, above right. Follow the links to find out more about the art movements that influenced these photographers. Try to find examples of paintings or sculptures that you can connect in one way or another to these images.

Windows of opportunities

|

...and panes of abstraction:

|

|

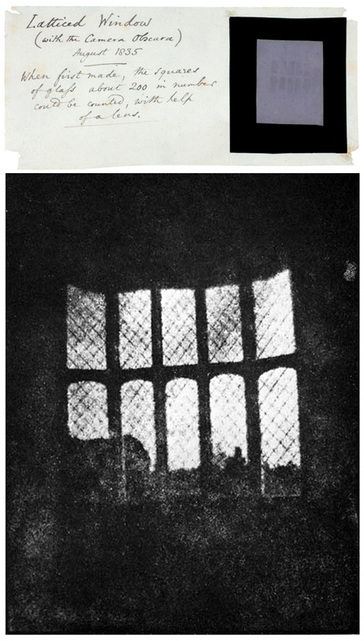

The early ambitions of photography were largely scientific (TC#1) - to document, describe, categorise and analyse - seeking solutions more trustworthy than an artist's hand. Niépce, for example, was fully aware of his own artistic shortcomings and, with an interest in both lithography and the camera obscura, sought to find alternative ways of accurate recording. That said, his and other early experiments (TC#2), such as Fox Talbot's Latticed Window (yep, another window) remain untrustworthy as documents due to technological restrictions - length of exposure, sensitivity to light etc.

That two of the earliest photos taken present views through windows is not much of a surprise: the framing of a fixed viewpoint, the glass between viewer and subject, the letting in of light (or not); windows are familiar apertures. From the camera obscura (latin origins: dark chamber or room) to Niépce, Fox Talbot and beyond, windows do make for illuminating subject matter.

|

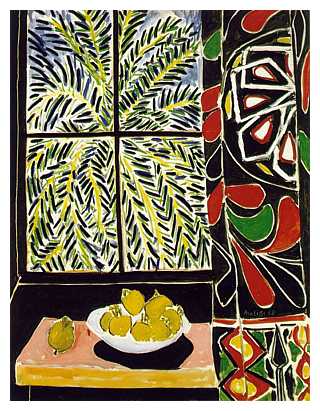

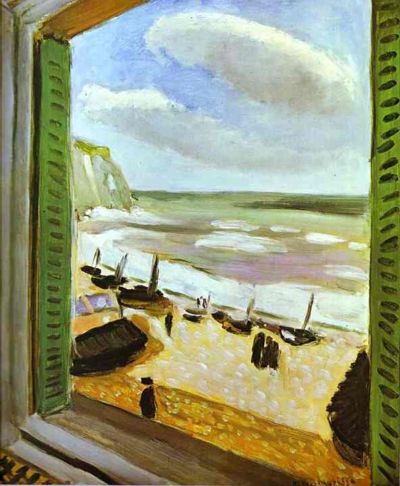

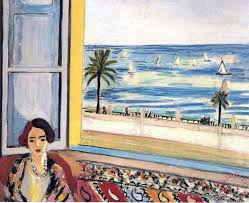

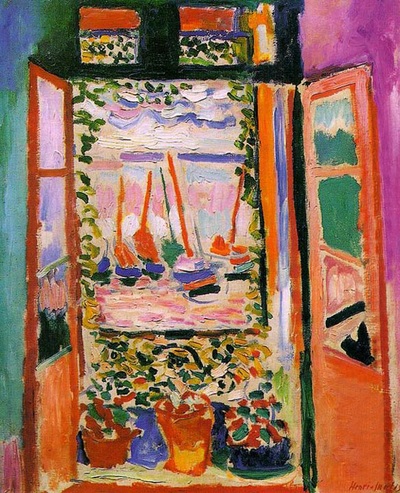

Matisse, a leading figure in the changing shape of Modern Art (so often shape when it comes to Matisse), was only 8 years old when Fox Talbot died in 1877, but he too was partial to a window view.

'French Window at Collioure', 1914, below, is perhaps the exception in a life full of rose-tinted observations. The painting's date provides a clue: World War I had began and France was in turmoil. Matisse - albeit momentarily - was struggling to see the light. It is by far the most abstract of his works, the base of the window shutter (bottom right of the image) is the only suggestion of perspective and depth, and this leads the viewer towards an uncharacteristic darkness; a field of non-colour no less.

French Window, 1914 is an existential statement by an artist caught in a world blackened by war |

Suggested activities:

Using the works above by Fox Talbot and Matisse as inspiration - and with reference to TC#4: Photography is an art of selection rather than invention - produce a set of images experimenting with the boundaries of representation and abstraction.

- How might adapting your camera settings disrupt the recording of what you see?

- How might your framing decisions - what to include (or not) - abstract, flatten, or distort the image?

- Could you use your photographs as inspiration for a painted abstract response? How might the feeling of painting compare to that of taking a photograph? What new opportunities or constraints arise across the different mediums?

Windows; inward, outward

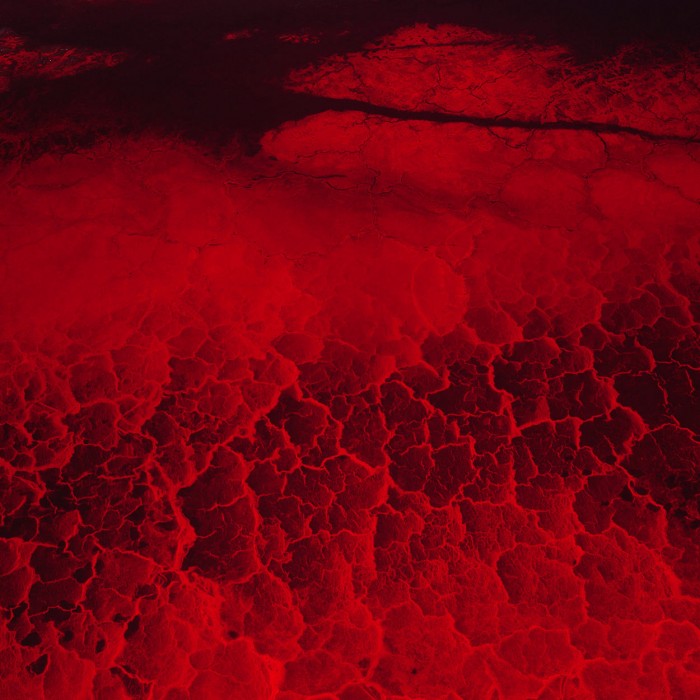

…pictures aren’t facts. There’s nothing factual about them. They’re mental space. That’s what abstraction is about, making a kind of psychological space.

-- David Maisel

"Maisel seeks a distance that scrambles a conventional reading of the landscape. In this altered state, the laws of gravity are undone, solid ground gives way, and the photograph is experienced as a transcendent vision or tone poem, as much as a map of ecological disaster. He uses this highly charged method of seeing to reveal the landscape in something other than purely visual terms, translating it as an archetypal space of destruction and ruin that mirrors the darkest corners of our consciousness." Diana Gaston |

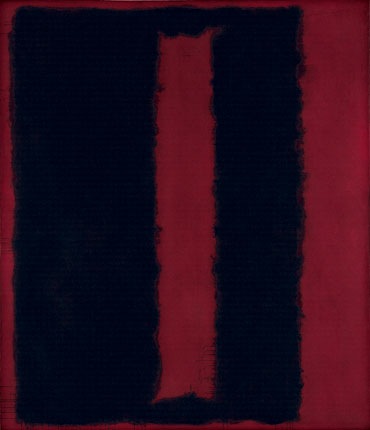

"Rothko's paintings seem to exist on the skin inside an eyelid. They are what you imagine might be the last lights, the final flickers of colour that register in a mind closing down. Or at the end of the world. "Apocalyptic wallpaper" was a phrase thrown at Rothko's kind of painting as an insult. It is simply a description; the apocalypse is readable in these paintings like a pattern in wallpaper - abstract, pleasurable horror." Jonathan Jones |

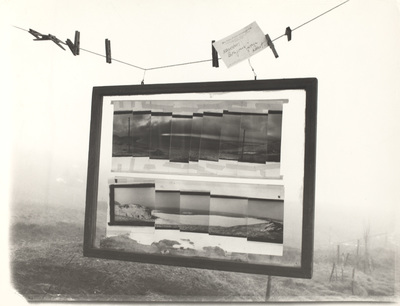

David Maisel is a contemporary photographer best known for his aerial views of environmentally impacted sites. His cartographies capture 'landscapes undone' in what might be considered an objective or representational manner. The images, taken from a propped open window (always windows) of a low flying aeroplane, present us with a view from above, as Maisel has chosen to frame it.

Mark Rothko was an American painter, prominent in the 1940s and 50s. Despite his objections he is generally considered as an Abstract Expressionist. Through his paintings he sought to express and engage with human emotions, aiming to provoke an experience akin to a religious or spiritual encounter - both for himself in the act of creation, and also for the viewer. The story of his Seagram Murals, devised in anger, inspired by the blacked out windows of Michelangelo's vestibule of the Laurentian Library in the Medici church of San Lorenzo, offers a fascinating insight into the mindset of an artist exploring abstraction.

Mark Rothko was an American painter, prominent in the 1940s and 50s. Despite his objections he is generally considered as an Abstract Expressionist. Through his paintings he sought to express and engage with human emotions, aiming to provoke an experience akin to a religious or spiritual encounter - both for himself in the act of creation, and also for the viewer. The story of his Seagram Murals, devised in anger, inspired by the blacked out windows of Michelangelo's vestibule of the Laurentian Library in the Medici church of San Lorenzo, offers a fascinating insight into the mindset of an artist exploring abstraction.

Suggested activities:

- Swap the descriptive quotes for the two images above. Do these still match equally well? Which parts of the text, if any, seem less or more relevant? What does this tell you about the nature of their work, or perhaps the nature of the descriptions?

- How much does context influence the shift towards abstraction in an image? - Is our reading of Maisel's photograph influenced by its proximity to the work of Rothko? Choose one of your own photos and experiment with placing (and re-photographing) it in different locations, exploring how its surroundings alter the reading of it.

- How has Maisel's use of technology - in all forms (for example the use of an aeroplane, as well as camera, lens etc.) - contributed to the truthfulness or abstraction of the image?

- How might this image have been more (or less) abstracted through the decisions made? For example, if Maisel had chosen to show the horizon line more clearly would the image be a more obvious landscape.

The examples above, in various ways, all demonstrate that abstractions emerge whether they are intended or not: Niépce and Fox Talbot produced works abstracted only through technological restrictions; Abstraction surfaced within Matisse's work at a time of personal darkness; Maisel's photographs appear as abstract works despite taking an objective approach to the landscape; Rothko was at pains to avoid being labelled as an 'abstract artist' yet is widely considered to be just this.

The next couple of examples concentrate on photographers that have made more deliberate decisions to embrace or even confront abstraction. And yes, more windows, for no reason other than playful connections.

The next couple of examples concentrate on photographers that have made more deliberate decisions to embrace or even confront abstraction. And yes, more windows, for no reason other than playful connections.

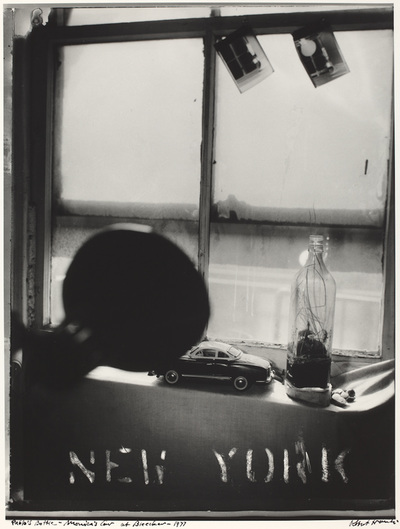

Robert Frank's multiple frames

|

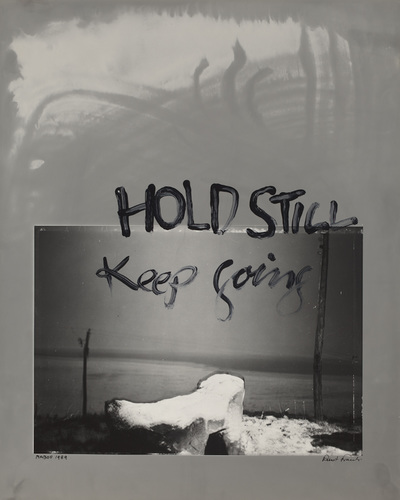

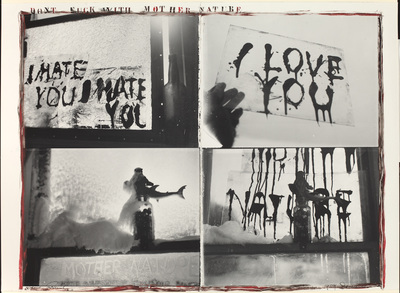

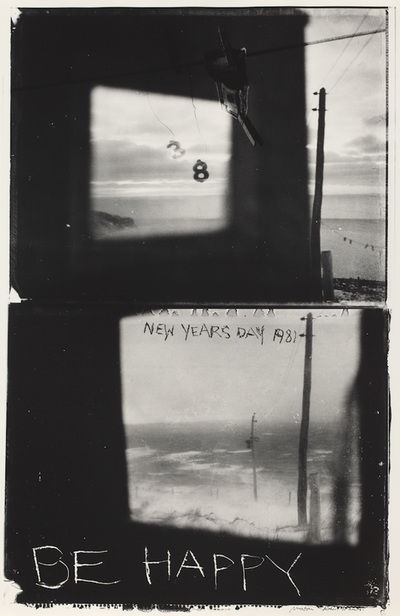

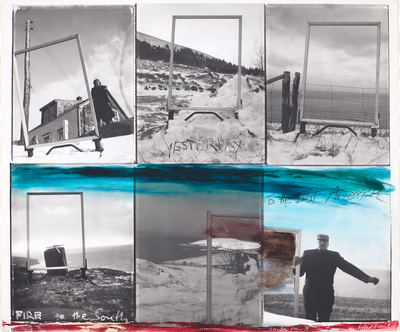

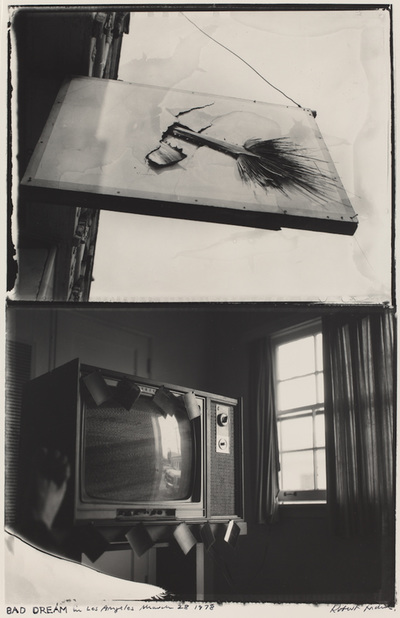

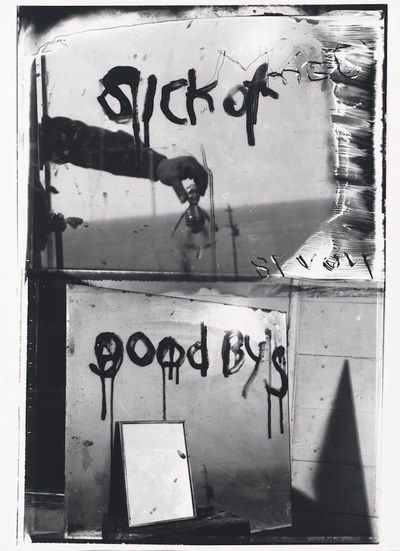

Robert Frank is most famous for his road trip across the USA that resulted in one of the most influential photobooks, The Americans. However, after a period in which he had given up making still photographs, preferring to make experimental films, Frank moved to remote Novia Scotia, returning to photography, but with a new, destructive attitude.

|

"I was really destroying the picture...I didn't believe in the beauty of the photograph any more." |

These images record powerful emotions, partly a response to tragic personal circumstances, loneliness and loss. Using a Polaroid camera, he created multi frame compositions, scratching into the film or painting across the surface, embracing the printing accidents that came with the technology. They unpick the notion of the single, decisive moment. Windows and mirrors feature prominently. There is a reflective (literal and metaphorical) quality to the images. They offer contradictory messages (I HATE YOU. I LOVE YOU; HOLD STILL, Keep going) and off-kilter views. The frame depicted within the frame often seems more important than the nominal subject - a hand, a landscape, a TV, a toy car, a house. These are views of the inside of his head as much as they are pictures of the outside world. Refer back to our original definitions of Abstraction; Frank is ticking all the boxes.

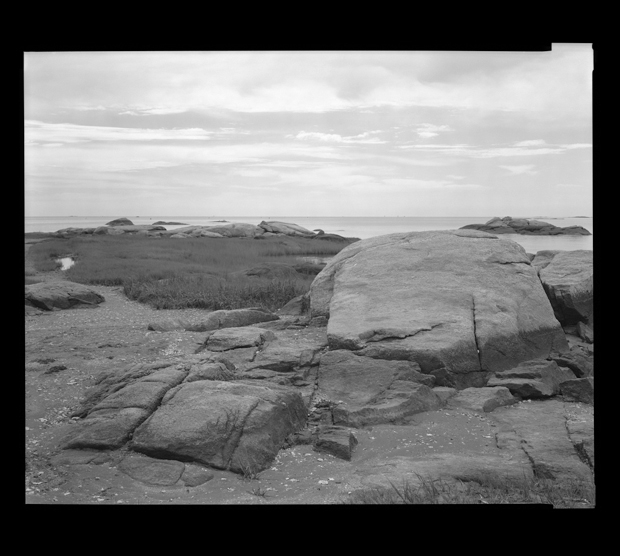

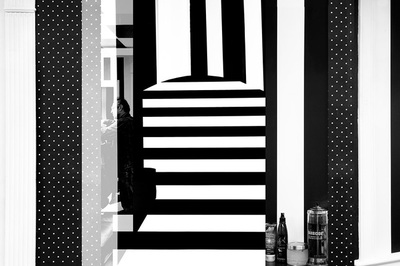

James Welling's Islands, in the frame

Compare and contrast these two images by the artist/photographer James Welling. Note down as many similarities and differences as you can...

|

|

It’s not that I don’t care about content, but content is not the only way a photograph has meaning. |

Welling appropriates the traditional conventions of documentary photography and sees other possibilities within his subjects - the photograph as an abstraction of visual experience Sarah Rogers |

.John Szarkowski wrote about photographs as if they were windows and/or mirrors:

Windows present us with the (illusion of) a view - the edges of the photograph being like a window frame. Do the defined edges in Welling's Chatfinch Island support this? Mirrors present us with a reflection of ourselves (the photographer), not literally, but in terms of how they express the photographer's state of mind and feelings about the world. Does Welling's Island (C67) hide a view and/or present a deeper reflection of something else? Look again at the photographs by James Welling. In what sense are they either windows and/or mirrors? |

Flat against the window

Art critic Clement Greenberg argued in his 1960 essay Modernist Painting that the essential and unique quality of modern painting was its flatness.

|

According to Stephen Shore (and many others) one of the key characteristics of photography is flatness (TC#8). He uses the following example by Lee Friedlander to explain how this works. A first glance at this urban landscape reveals some typical Friedlander concerns - a liminal, uncared for space; a disruptive central subject and its shadow; echoing forms - caravan and car, tree and tree, a road to nowhere etc.

But look more carefully. In what appears to be a conventional foreground/middle ground/background the picture space is disrupted by the presence of a cloud appearing to sit on top of the sign. It has become an ice cream cone. We know that the cloud is a long way away and the sign almost within touching distance of the photographer, BUT they have been flattened by being photographed. In this case, both ice cream and photography are flattening. |

Other artists, such as John Baldessari and Annie MacDonell have explored this concept of flattening, of how photographs transform (abstract) rather than just simply represent the world around us. Stephen Gill, in his series Hackney Flowers, emphasised the flatness of photography by layering upon the surface prior to re-flattening / re-photographing.

Suggested activities:

- Produce your own Baldessari inspired experiments exploring the 'flatness' of photography. Pay particular attention to the importance of aperture settings / depth of field in creating a more convincing illusion.

- Read the description below from Annie MacDonell regarding her own work. In this she hints at the seismic shift that has taken place in how photographs are taken, highlighting that a digital image - each one a unique sequence of binary information - is far removed from a photograph in its traditional sense, as a direct recording of light.

- Choose a photo that is of particular importance to you. Using only sequences of typed numbers, create an alternative version of this, which might be visually similar, but alternatively might take a more conceptual approach e.g. devising a code from which information may (or may not) be able to be deciphered.

- Using Stephen Gill's Hackney Flowers series, experiment with layering and flatness. However, rather than doing so upon the surface of the image, think of alternative 'live' approaches, for example, placing objects upon mirrors. Or windows.

By Chris Francis and Jon Nicholls