|

These resources have been developed in partnership with The Royal Photographic Society (RPS) in support of the Science Photographer of the Year competition and exhibition. The 2021 exhibition was on show virtually through the Manchester Science Festival website. The resources have been devised for KS3-5 students, but are adaptable for younger years. An online visit to the exhibition would be highly beneficial but is not essential to explore these thought-provoking themes.

The Royal Photographic Society exists to educate members of the public by increasing their knowledge and understanding of Photography, and in doing so to promote the highest standards of achievement in Photography. Click here to discover more. |

Seeing Science

We are creating this resource during a global pandemic. Whilst we hope these resources will have a long shelf-life, it's worth remembering that the relationship between science and photography is brought into sharp focus by current events. How can photography (or photographic imaging) help us 'see' something so huge and microscopic, so complex and invisible, as a pandemic?

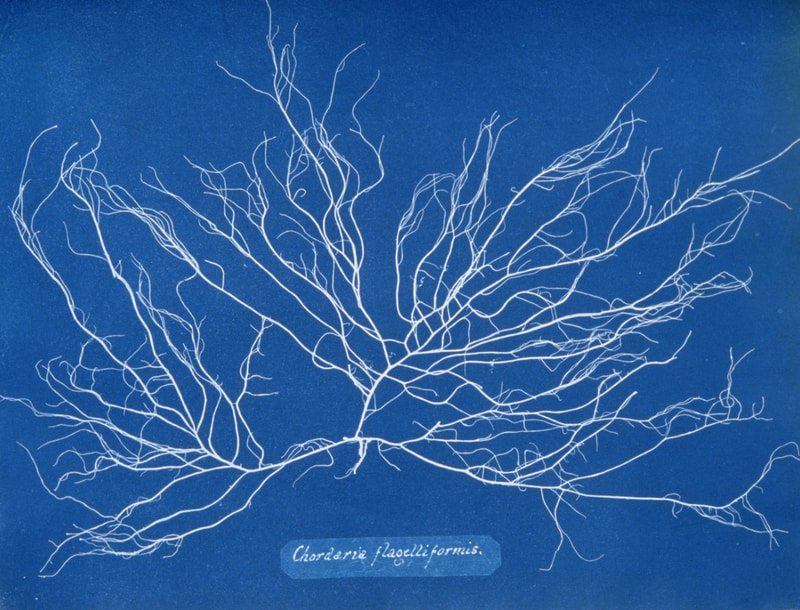

Photography, born of and shaped by science, transformed the nature of observation and stretched the parameters of knowledge and humanity's sense of itself [...] Photographs were immediately marshalled into service to help answer the most practical and existential of questions: What is that? Where and who are we? What happens next? Photography bridges the worlds of science and the arts. Photography's 'birth' in the mid nineteenth century was a collaboration between scientists, keen to discover a reliable chemical process for fixing light on a flat surface, and artists searching for new ways to look at and capture the visible world. Sometimes, the scientist and artist could be found in the same remarkable individual. William Henry Fox Talbot, for example, was both an amateur artist and scientist. Anna Atkins was a botanist with a keen eye for aesthetic beauty.

Today's smartphones and mirrorless digital cameras are technically sophisticated. They provide us with high quality images but they also make the technical and scientific processes of creating these images largely invisible. We might be tempted to forget how scientific our photos are. Today's global challenges - climate change, Artificial Intelligence, the Internet, poverty and pandemics, for example - are so HUGE that it's often difficult to 'see' them. Philosopher and Ecologist Timothy Morton describes them as hyperobjects. This ability to 'see' a problem, to grasp its importance, is key to finding a solution. Photographs can help us see a reality that is invisible to the naked eye. |

Writing on the eve of WW2, Berenice Abbott wrote a manifesto about the importance of photography for science:

Today science needs its voice. It needs the vivification of the visual image, the warm human quality of imagination added to its austere and stern disciplines. It needs to speak to the people in terms they will understand. They can understand photography preeminently.

-- Berenice Abbott, 1939

One only has to reflect on the ways in which the Nazis used both science and photography to commit crimes against humanity to realise that those who understand this relationship have enormous power. The history of photography and the history of science are bound together. They face similar ethical issues. Scientists and photographers have power and they haven't always used this power responsibly. Public knowledge about science and photography is important because the more we know about these disciplines, the better chance we have of understanding and acting on the stories they tell for the common good.

What follows are a few ideas, prompts, suggestions and activities designed to encourage you to reflect on the science of photography and the photography of science.

What follows are a few ideas, prompts, suggestions and activities designed to encourage you to reflect on the science of photography and the photography of science.

For discussion

- What is scientific about photography? How are scientists and photographers similar?

- How do cameras 'see' the world differently to the human eye?

- When you think of a scientific photograph, what kind of image comes to mind? Try an image search for 'science photograph' online. What appears?

Timeline

This interactive timeline on the Seeing Science website is a great way to familiarise yourself with the relationship between science and photography stretching back to the early middle ages! As the poster says, "Without SCIENCE, you wouldn't be taking that picture."

Part 1: What is that?Photographs appear to look just like the world we see with our eyes. However, a photograph changes the thing photographed. Soon after the 'invention' of photography in the mid nineteenth century, artists and scientists began to realise that they could transform the public's understanding of the world through the medium of photography. Photographs had the ability to reveal, startle, confuse and estrange.

The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious In the early twentieth century, photography became part of an avant-garde attempt to capture the spirit of technology - a new way to see 'progress', at least in industrialised economies. Some contemporary artists use photography to ask playful questions about what can be seen and believed.

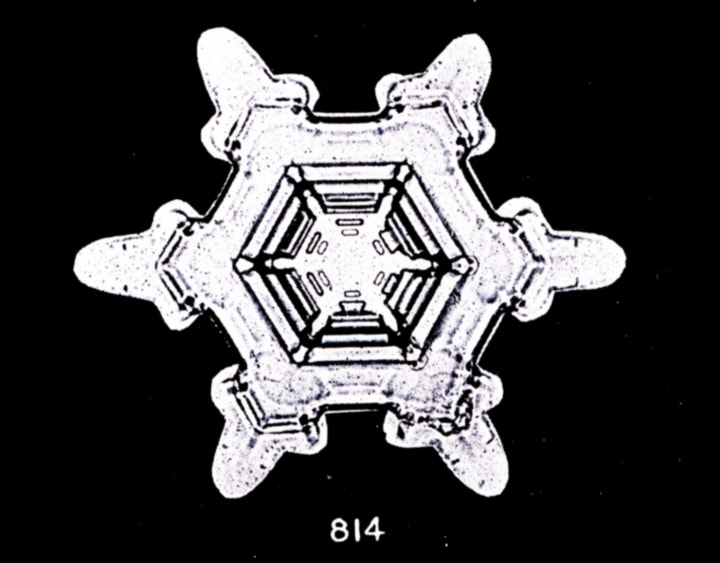

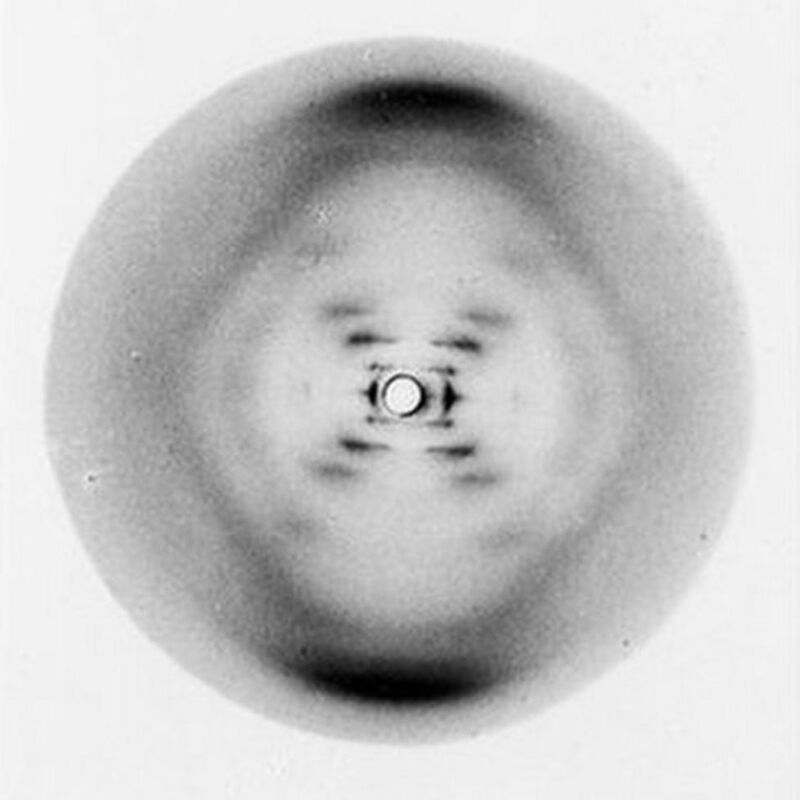

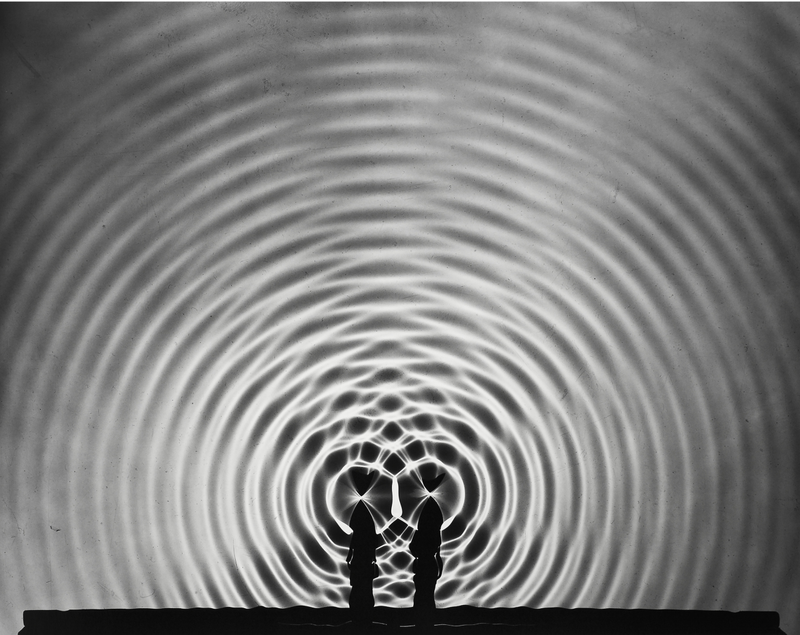

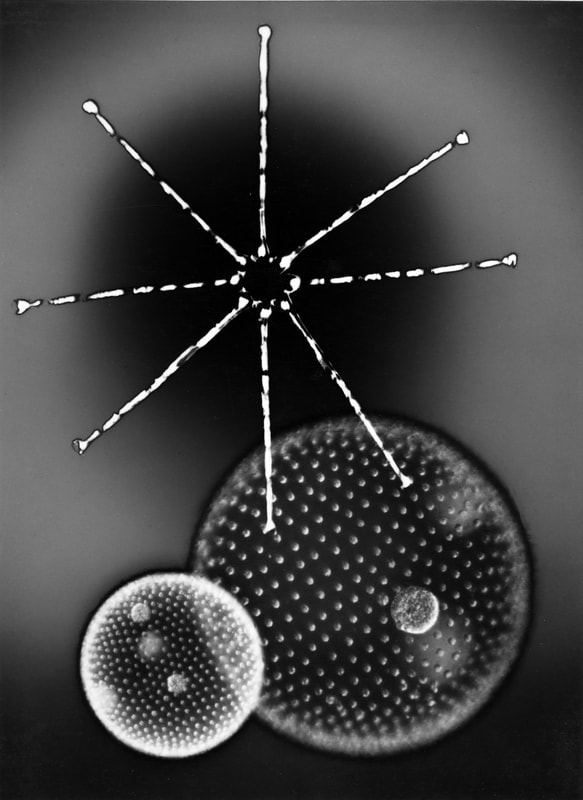

Take a look at the following images. Each is a famous photograph used in the service of science. Before you click on the individual images to find out more about them, can you guess what they depict? What do they suggest? How do they make you feel? Part of the charm of images like these is that they are both descriptive and ambiguous, factual and poetic. |

It's tempting to think that science and photography share a concern for objectivity, truth and rational explanation. This is only partly true. Some of the greatest scientific discoveries owe as much to the imagination as to observation and photographs are much less reliable documents of reality than we sometimes suppose.

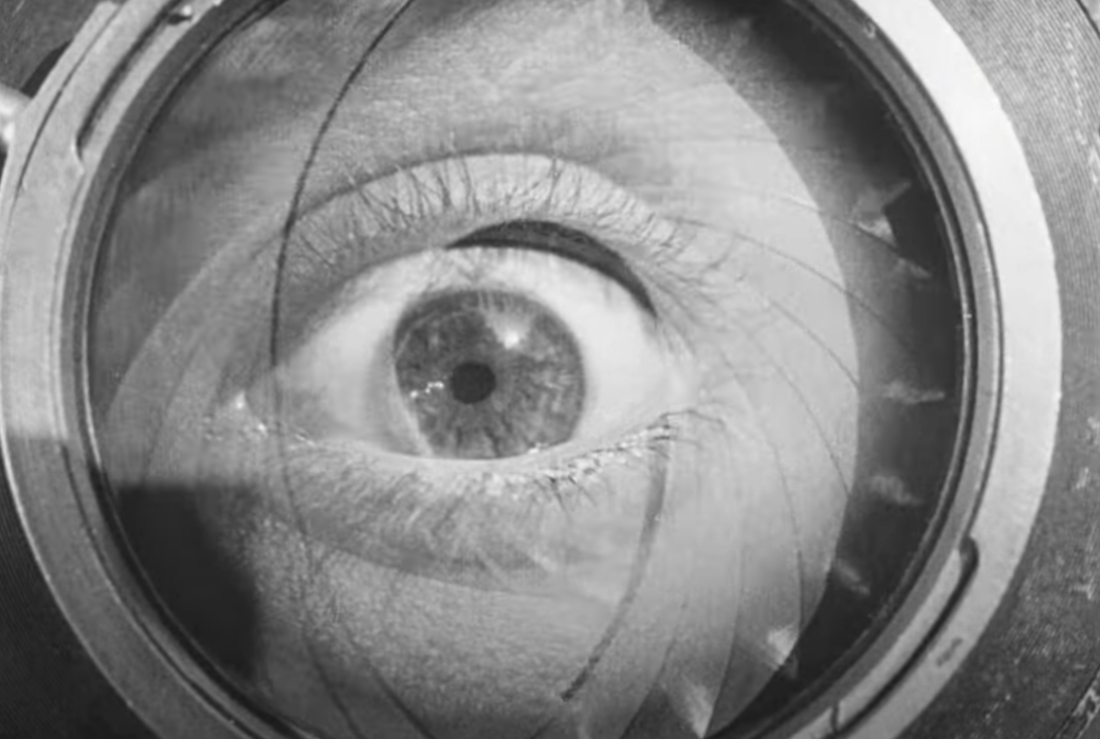

Threshold Concept #5: Abstractions shaped by technologyCameras ‘see’ the world differently to the way we see the world with our eyes. Cameras generally have one eye (monocular) whereas we tend to have two (binocular). Camera lenses can produce images with variable focus. The camera shutter can halt the flow of time and, with the aid of flashes, can stop a bullet in mid flight. Photographic imaging has enabled us to see through solid objects. All photographic images have been shaped by the technology the photographer chooses and by a process of selection, editing and manipulation. Each and every photographic image is therefore made or constructed, rather than being a window onto the world.

In photography we possess an extraordinary instrument for reproduction. But photography is much more than that. Today it is [a method for bringing optically] some thing entirely new into the world. Seeing photographically requires an understanding of the special and unusual ways in which cameras (of various sorts) represent reality and the specific attributes of photographic images.

|

For discussion

- What are the differences between photographs of things and the things themselves?

- When would you choose to look with a camera at the world rather than just your eyes?

Related PhotoPedagogy resources:

|

The Surface of Things Photographs capture the light reflected off the surfaces of objects. Scientists are fascinated by the material properties of things in the world. How might you make a careful photographic study of the physical properties of the objects you use everyday? |

|

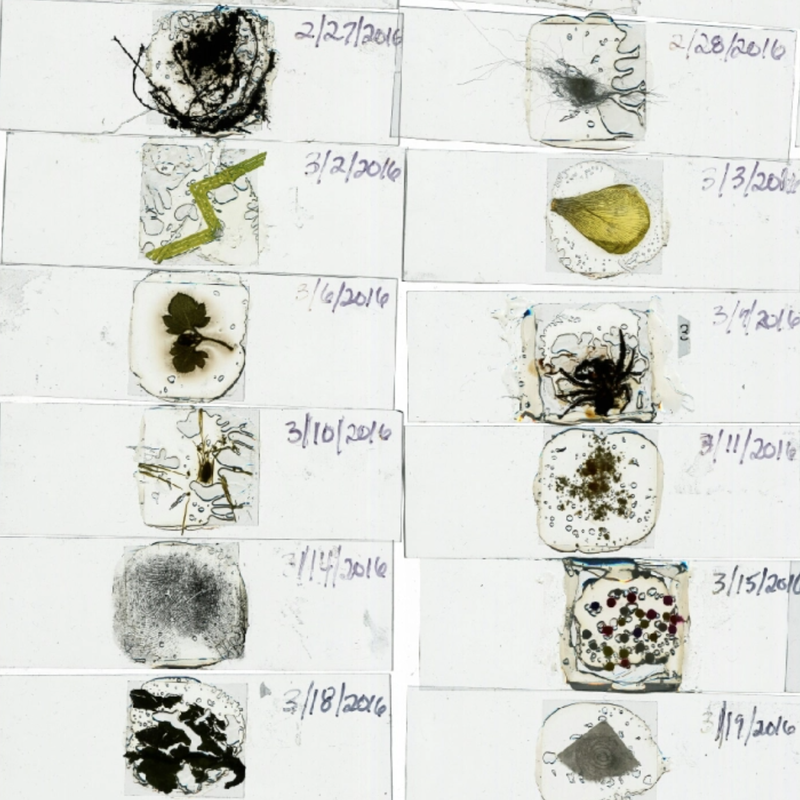

Typologies Photography has been used by both scientists and artists to classify, organise and present particular phenomenon in museum-like displays that encourage the viewer to analyse, compare and assess aspects of the world around us. The process involves gathering comparable photographic 'evidence' of people, objects or places. How might you create a typological study of something that interests you? |

Part 2: Where and who are we?

Take a look at the image below. What do you see?

|

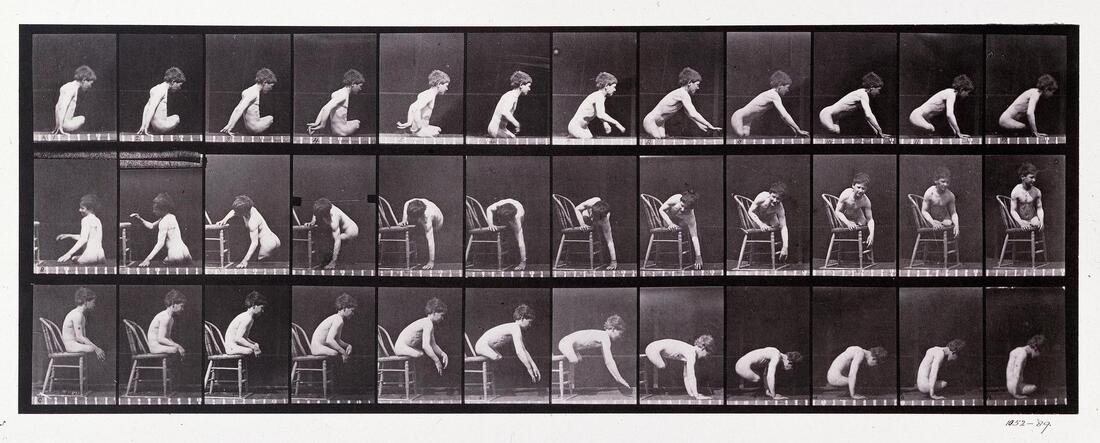

Eadweard Muybridge is famous for having discovered, with the aid of a specially rigged sequence of photographic cameras, that a horse's legs all leave the ground simultaneously for a split second. Prior to Muybridge's discovery people had depicted horses running in various strange ways because the human eye could not perceive the truth. However, Muybridge used the visual acuity of his cameras to look at other mobile subjects, including the human body. How do we feel when we look at images like the one above. A young boy, a double amputee, is asked to shuffle across the floor, climb onto and off a chair, so that the sequence of his movements can be 'objectively' observed by the cameras' lenses.

|

|

|

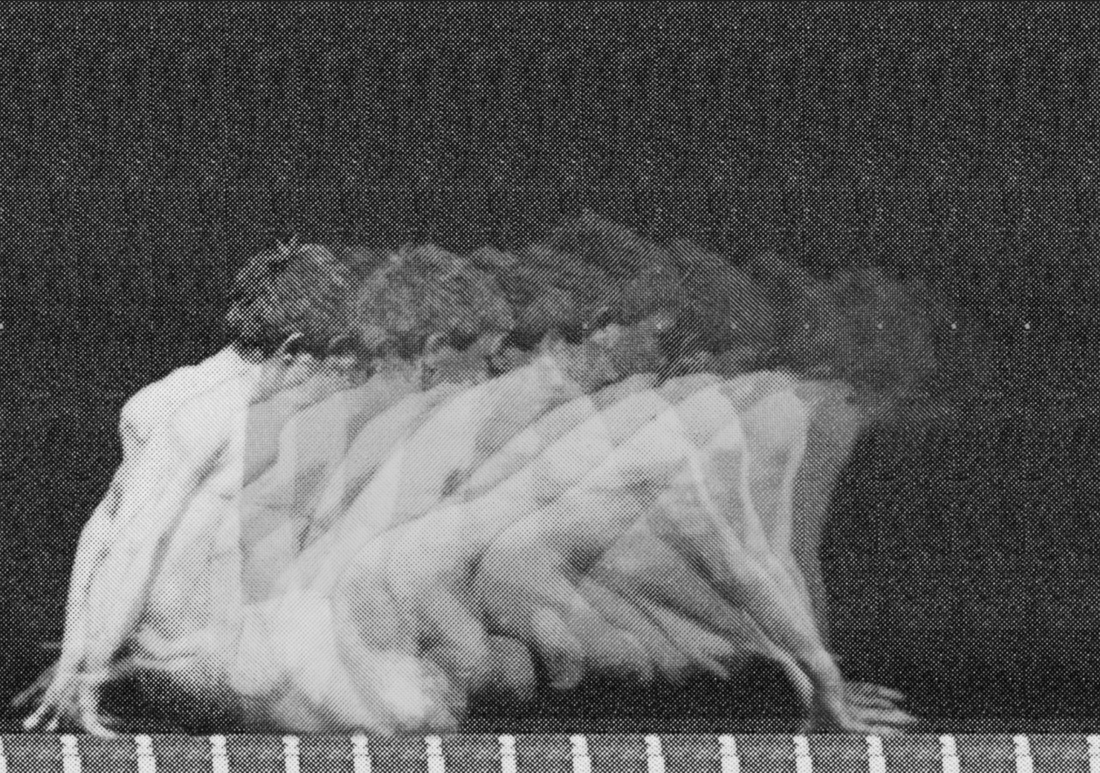

To a contemporary audience, Muybridge's gaze might appear cold, calculating and detached. Photography has been complicit in supporting unethical, inaccurate and racist scientific attitudes. The contemporary artist Idris Khan uses a process of digitally layering 'found' photographs from the history of the medium. When the separate frames of Muybridge's sequence are superimposed (Fig. 3) a beautiful animation-like image emerges. However, we might also be reminded of the work of nineteenth century scientist and eugenicist Francis Galton, who used a similar technique to create composite portraits of racial, criminal and familial characteristics.

Why did he choose photography to help promote his dubious theories? Photographs are persuasive precisely because they look like reality. We have photographs of ourselves in our passports, rather than drawings or paintings, because a photograph appears to tell the 'truth'. And yet we only have to look at the two photographic images in Figures 2 and 3 to realise that photographs are much stranger than they seem. We don't tend to 'see' the photograph, the light-sensitive piece of paper or digital screen, only the thing photographed. Despite the fact that we know about Photoshop and image manipulation, we still tend to believe that a photograph is a facsimile, a copy, of reality and is therefore a reliable document. |

|

Scientists and photographers are similarly concerned about our common humanity. What makes us feel, think and behave in the ways that we do. How do we relate to each other and the world around us?

Let's try a quick experiment:

The missing part of the title of this image is: FEAR: REACHING THE FOUR DEGREES OF WARMING We don't always think of scientists as emotionally vulnerable. Our stereotypes of scientists probably include either a lab coat, glasses and a stern expression or something closer to Drs Frankenstein and Jekyll. This series of portraits called 'Scared Scientists' reveal a shared sense of anxiety about the future. These scientists look a bit like us. These are family portraits of the human species. |

Consider another pair of photographs:

It's hard to tell the story if you don't have a stunning image to back it up

-- Ray Villard, public relations director for the Hubble Space Telescope project

Both of these pictures encourage us to consider our relationship to planet Earth. Both look down at our planet. Both are disconcerting and might provoke feelings of awe caused by a sense of vastness. 'Earthrise' (Fig. 5) shows the Earth from space with the Moon in the foreground. The amazing story of how this iconic picture was made can be viewed here. The violent worldwide street protests of 1968 are invisible from this perspective and yet the image is often credited with inspiring a rejuvenation of environmental awareness. From this distance, the Earth appears united, whole, beautiful and tiny in the enormous expanse of space. Trevor Paglen's photograph of the sea bed (Fig. 6) captures the vastness of the Earth's oceans, a mysterious and largely undiscovered realm. If we look carefully, we can just about make out some cables running along the sea bed. These are part of a largely invisible network carrying data for global communications.

For millennia, artists and mystics have pondered the question of how to represent that which, by definition, cannot or must not be represented.

-- Trevor Paglen

Threshold Concept #7: Photographs are not neutralPhotographs are not neutral; they are susceptible to the abuse of power. Photographs communicate powerful ideas about the world. They can be used to promote both good and bad attitudes. Photography can be a powerful force for good, showing us a world we would otherwise not be able to comprehend. Photography, like science, has been concerned with a search for the truth. However, both disciplines only present us with a best guess, a theory about what the world is like and who we are as a species. Students of photography must therefore be very careful to think hard about what they see in other people's photographs and how they make their own.

For discussion

|

Related PhotoPedagogy resources:

|

The Photograph as Evidence Since its 'invention' in the 1830s, photographs have been used as sources of evidence. The direct (indexical) relationship between the sun's rays and the resulting image makes photographs seem reliable as sources of information. But how reliable are photographs, really? |

Part 3: What happens next?

|

In the 1920s and 30s some artists embraced the technologies of photography and film-making in order to present a vision of the future, a utopian paradise in which rapid industrialisation and the miracles of science would release man (sic) from the shackles of labour. The human eye and the camera lens often became fused, as in Dzigo Vertov's 1929 film Man with a Movie Camera.

What does the future look like? When does science become science fiction? How has photography been used to share a vision of the future with the general public? The new world will not need little pictures. If it needs a mirror, it has the photograph and the cinema. |

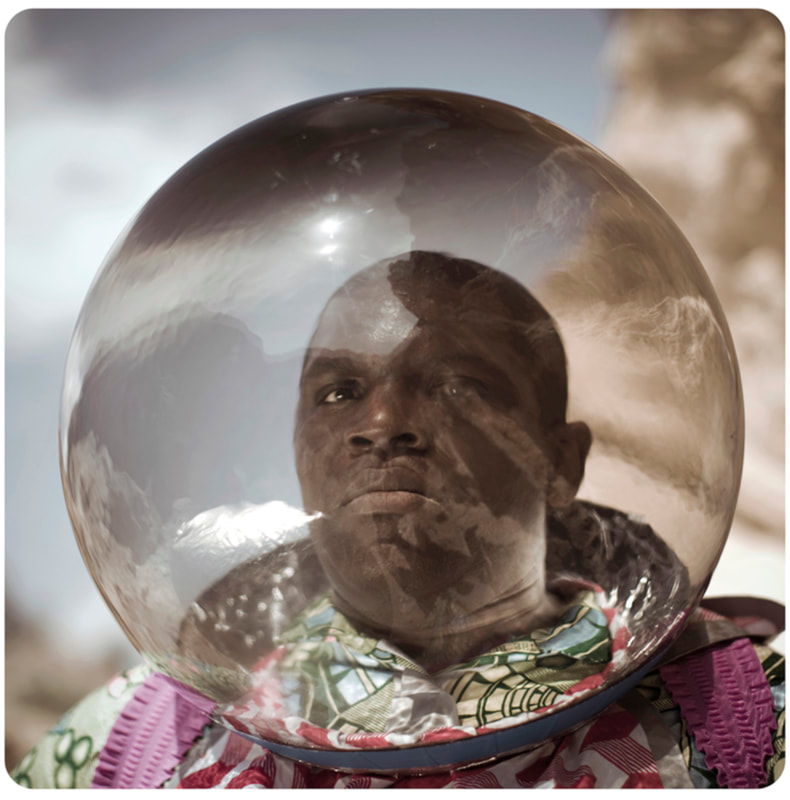

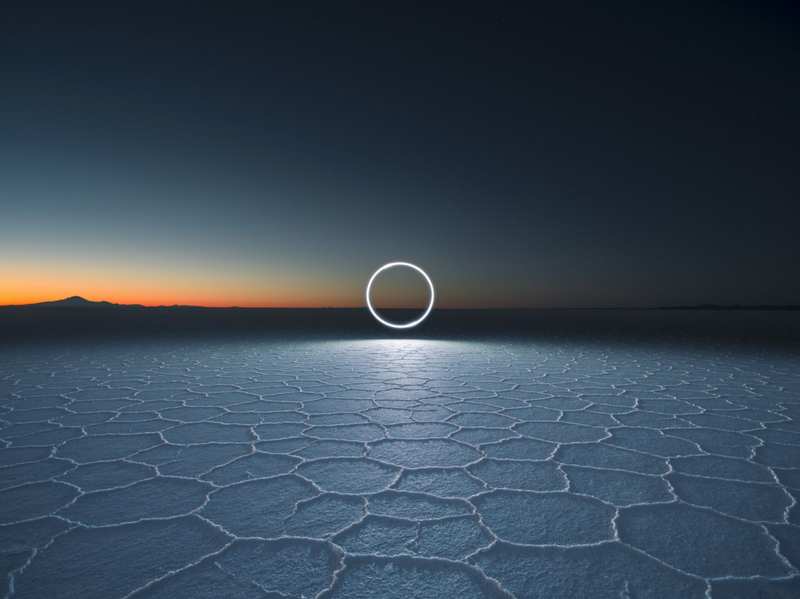

Since then, our skepticism about a brave new world has increased. Science and technology has certainly improved the lives of millions of people across the globe, lifting them out of dire poverty and creating vaccines for previously incurable diseases. However, this has come at a great cost. We now face a climate emergency, an ever increasing gap between rich and poor, mass migration as a consequence of globalised trade and a worldwide pandemic! Because of their persuasive power, photographs can help to convey a vision of the future.

Take a look at the following images. What do they suggest to you? Clicking on the image will take you to a website with more information about it.

Take a look at the following images. What do they suggest to you? Clicking on the image will take you to a website with more information about it.

Threshold Concept #2: Photography is democratic & diversePhotography crosses different disciplines both in theory and practice. It is a hybrid form of art informed by the sciences and the humanities. Photography is also the most diverse and democratic of the visual arts. It has multiple functions, contexts and meanings. These sometimes overlap in interesting ways.

Most of the billions of photographs that are taken with cameras every year are made for purposes that have nothing to do with art. They are made for quite specific reasons, some exalted and some mundane, and their value is dependent on how well they serve a purpose that, more often than not, has nothing to do with photography itself. For discussion

|

Suggested Activities:

The following activities are just a few ideas to get you thinking about and making scientific photographs. It's tempting to think that science and photography are only for specialists with fancy equipment. Nothing could be further from the truth. It's important that we all engage in both science and photography because they help us understand the world we live in so that we can change it for the better. Have fun!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other resources:

Revelations: Experiments in PhotographyEarly scientific imagery such as X-Ray, photomicrography and experimental high-speed photography exposed and surpassed the limits of human vision. In doing so, it revealed important formal possibilities to artists, and spoke to them in clear and articulate terms about man’s changing relationship to science and technology. Drawing on the National Collections held in Bradford and London, and further international collections, a selection of photographs, book spreads and other documents demonstrate new modes of representation established by early scientific photography and their profound impact on the histories of photographic art. Here is a video of Dr Ben Burbridge discussing the 2015 exhibition at the Science Museum.

|

Seeing Science: How Photography Reveals the UniverseSeeing Science offers an insightful and reader-friendly collection of essays and pictures about photography’s role in visualising science and building human knowledge—from micro to macro levels and everything in between.

Photography and science have long been intertwined, helping to shape the way we look at the world. Scientists use photography as a way to gather information, explore, and learn, but just as important, photography is also used to promote scientific advances and has long served as an interface between the sciences and the public. Here is a video of author Marvin Heiferman discussing the book. |

|

If you have any queries regarding these resources, or if you would like to share any student work produced in response to these themes, you can contact PhotoPedagogy here.