Jon Nicholls, Thomas Tallis School

|

Since its 'invention' in the 1830s, photographs have been used as sources of evidence. The direct (indexical) relationship between the sun's rays and the resulting image makes photographs seem reliable as sources of information. No wonder that photography was enthusiastically embraced by organisations like the police who began to use photographs as sources of legal proof. And yet, from the beginning, artists working with photography began to create images which relied on the manipulation of their photographs using techniques like combination printing, undermining their evidential status. Photographs are very persuasive since they look so much like the things photographed. As Susan Sontag has pointed out, when we hear about something happening but doubt its occurrence, we tend to believe it to be true when shown a photograph of it. However, she also describes the way that photographs are peculiar in the type of evidence they provide:

The photographer was thought to be an acute but non-interfering observer – a scribe, not a poet. But as people quickly discovered that nobody takes the same picture of the same thing, the supposition that cameras furnish an impersonal, objective image yielded to the fact that photographs are evidence not only of what’s there but of what an individual sees, not just a record but an evaluation of the world. It became clear that there was not just a simple activity called seeing (recorded by, aided by cameras) but ‘photographic seeing’, which was both a new way for people to see and a new activity for them to perform. |

Several of the Threshold Concepts for Photography seem relevant here. Photographs look like reality but are, in fact, abstractions. Their abstractness is a consequence of the visual language with which they are formed. Photographs are selections from the available evidence, partial views of the 'big picture' that have been carefully framed by the photographer. Given the relationship between evidence and power, the ways in which photographs have been used and abused by authority over the years, and the methods contemporary artists have deployed to undermine or question the evidential nature of photography, Threshold Concepts #9 also seems apt. However, as John Tagg noted in his book 'The Burden of Representation':

every photograph is the result of specific and, in every sense, significant distortions which render its relation to any prior reality deeply problematic [...] The indexical nature of the photograph - the causative link between the pre-photographic referent and the sign - is therefore highly complex, irreversible, and can guarantee nothing at the level of meaning.

-- John Tagg

Consequently, Threshold Concept #7, which deals with the meanings of photographs and their varying contexts, is perhaps the most relevant here.

Some initial questions:

- What can photographs be evidence of?

- How many types of photographic evidence can you list?

- Which of your official documents include a photograph of you?

- Why are photographs considered, in some legal circumstances, to be a reliable source of evidence?

- How reliable is your Instagram feed or family photo album as a record of your life?

This project is designed to explore the idea of photographs as forms of evidence. Of course this is relevant to all photographs. To what extent can any photograph be relied upon to tell us the truth? It might be more fruitful to confine our exploration to those images which purport to be forms of evidence - a record of some thing, person or event beyond its aesthetic value. The project also asks some questions about originality, appropriation and authorship. These issues are central to contemporary artistic and photographic practice and students should be alert to them. Is the photographer always the one who presses the shutter?

Take a look at the photographs below:

Take a look at the photographs below:

Some questions:

- What can you deduce about the types of evidence provided by these photographs?

- Can you detect any similarities between them?

- What additional information might you need for these images to be considered more reliable as a source of evidence?

|

Artists Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel selected these and other photographs from a variety of archives, sequencing them and publishing them in their book 'Evidence' in 1977. Here's artist Catherine Wagner talking about the sequence of images on display at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. A generation of artists in the 1970s began to question the meanings of photographs, adopting practices that deliberately undermined the authority of the photographic image. Sometimes referred to as The Pictures Generation, artists such as Sherrie Levine and Richard Prince used strategies like appropriation to explore the ways in which photographs represent reality.

Contemporary artists have continued to explore the possibilities of appropriation in their practice. The images opposite are by Anne Collier. She re-photographs existing images in the studio using a large-format plate camera. These include book covers, magazines, record sleeves, and posters from the 1960s, 70s and 80s . She explores issues of consumerism, feminism, and voyeurism which emphasise the way photography frames information, creating new, slightly altered, realities. Sara Cwynar is interested in kitsch - over-familar, excessively sentimental images drawn from popular culture - and has constructed her own Kitsch Encyclopedia. Erin Shirreff re-photographs images she finds in a old publications, using a variety of light sources, to create seamless video sequences. |

|

|

|

|

Some suggested activities:

- Search for specific hashtags in Instagram, as photojournalist Thomas Dworzak has done, in order to compile your own collection of visual evidence. Consider creating your own handmade photobooks featuring these appropriated images, referring to Dworzak's books and the practice of Richard Prince.

- Inspired by Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel, se the Flickr Commons to search for photographs. Create a system of your own for selecting search terms and images. Arrange your selected photographs in a particular sequence. Decide whether you will give them a title and/or captions or whether you would prefer to give the viewer more control of the meaning making process.

- Re-photograph reproductions your favourite photographs by a particular artist so that they look almost identical. You may decide to attempt an exact facsimile or you might introduce a clue that it is a(another) reproduction - a stray object, a crease or fold, a reflection, an edge revealed etc. Think about what you are contributing to the original photograph. How have you altered its meaning? Now, re-photograph some of your own images. What effect does this have on them? You may want to check out Walter Benjamin's seminal 'The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction'.

Fake News

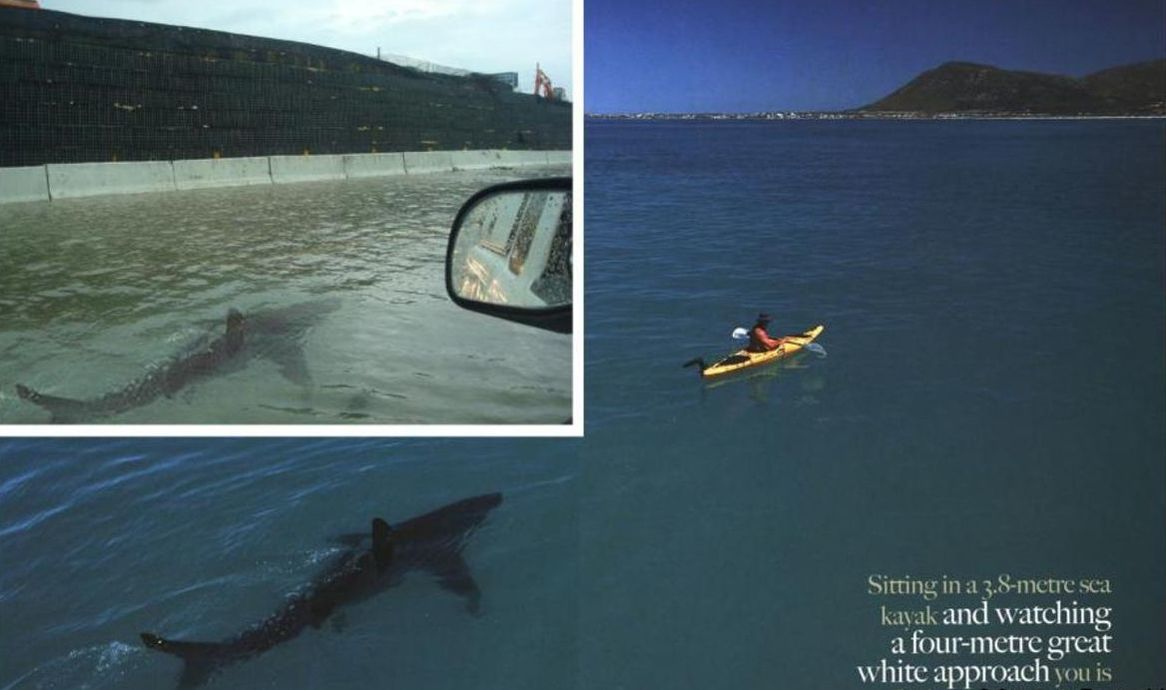

We live in a era of "fake news". The recent presidential election in the United States has provided us with hundreds of examples. The speed and ease with which fake news stories can spread via social media is part of the reason. The fact that those who spread fake news stories can earn a fortune from advertising is part of the attraction. However, nothing convinces people of the apparent 'truth' of a story than seeing it in a photograph. Take the following example:

|

After 2011’s Hurricane Irene, a photo of a shark swimming down a flooded Puerto Rican street hit the web. The shark, it was later discovered, was digitally pasted in from a real encounter at sea.

Spot the difference? Doctored photographs are relatively common in the world of politics. Josef Stalin often ordered that official photographs were retouched to remove those who had fallen out favour with the regime. Winston Smith, the 'hero' of George Orwell's '1984' works in the Ministry of Truth re-writing history by editing the evidence in daily newspapers and official documents.

|

When we're faced with doctored images, even if up front if we know they’re fake, over time we may remember the image but not remember knowing that it's doctored.

-- Kimberly Wade

Doctoring images is one thing but fake news can still be made by misusing photographs as forms of evidence. Inventing captions, presenting unrelated images side by side and cropping are all ways of exploiting the believability of photographs.

|

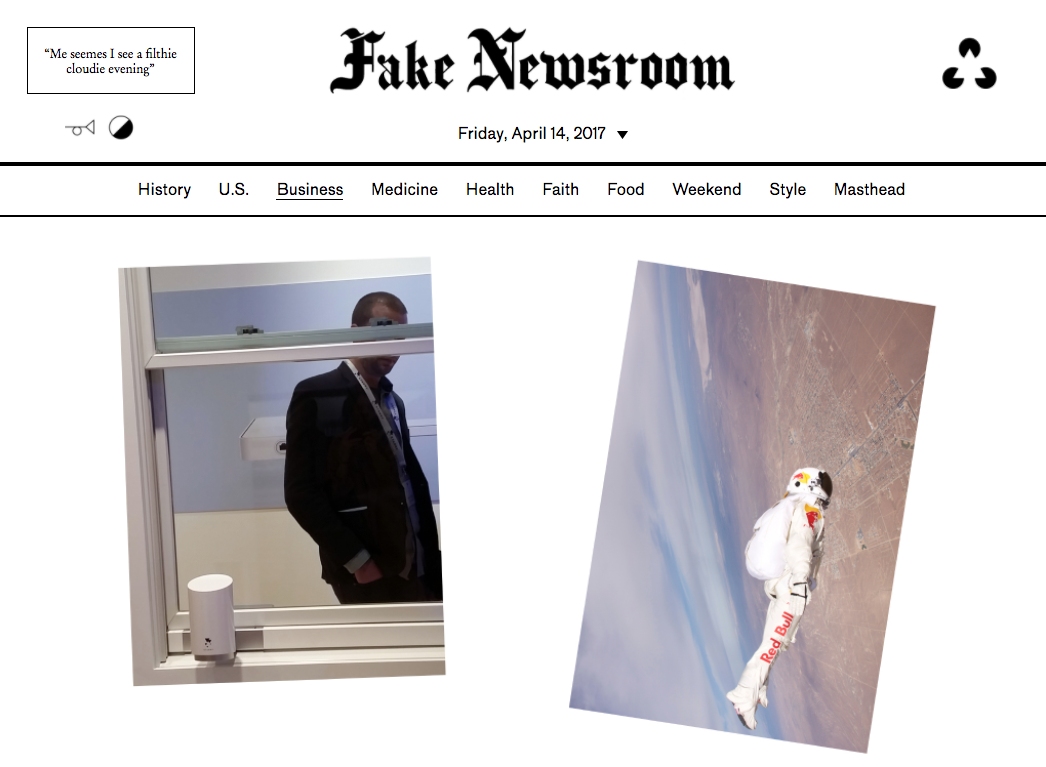

In 1983 Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan installed electronic news and wire photo machines from Associated Press and United Press International—the same content used by daily newspapers—into the Berkeley Art Museum. Each day, for several weeks, they worked as news editors in the gallery, selecting images and text from the news feed, and arranging them on the museum walls. This April, Fake Newsroom, a recreation of Mandel and Sultan's original project, was established in the gallery at Minnesota Street Project in San Francisco, edited by Jason Fulford.

|

Suggested activity:

Set up your classroom as if it was a fake newspaper office. Gather news stories and accompanying photographs from a variety of sources. Discuss roles and responsibilities. How will you use the physical spaces in your classroom to make decisions about selection and layout of images? How will you use resources such as printers, scanners, photocopiers, computers, (even the darkroom), to produce your images? How will you decide which images accompany which stories? Will your newspaper include text and images or just images? Use the tools at your disposal to produce a fake newspaper.

You could, for example:

You could, for example:

- photocopy your newspaper and distribute within school

- create a simple online newspaper (blog or website)

- use a site like Newspaper Club to make a very realistic looking product full of fake news

Permanent records

|

Of course, most photographs are not made to be works of art. The relationship between photographs and evidence was explored by The Photographers' Gallery in an exhibition entitled 'Burden of Proof' in 2016.

Featuring images taken as evidence of crimes or violence against individuals and groups, the exhibition explored the role of the forensic expert in relation to photographic images. The subtitle of the show is telling, 'The construction of visual evidence'. Diane Dafour, the curator, discusses three different ways in which forensic experts have used photography to provide evidence:

|

|

She reminds us that photographs often require the addition of words to secure their meaning:

People tend to think that the image, in itself, is an evidence or that the image, in itself, is almost never an evidence. It has to be validated, legitimised, interpreted, read and delivered by an expert who is providing words.

In 2016, the Michael Hoppen Gallery curated an exhibition of photographs entitled '? The image as question: an exhibition of evidential photography'.

The exhibition featured a wide range of photographs from fields such as medicine, conflict, engineering, astronomy and crime. Originally used as evidence of something, torn from their original context and hung on a gallery wall, the photographs could be appreciated for their aesthetic qualities and artistry.

A limited edition of 200 catalogues were produced to mark the show, again conferring on the photographs the status of art object:

Part of the fascination with all photography is that the medium is firmly grounded in the documentary tradition. It has been used as a record of crime scenes, zoological specimens, lunar and space exploration, phrenology, fashion and importantly, art and science. It has been used as ‘proof’ of simple things such as family holidays and equally of atrocities taking place on the global stage. Any contemporary artist using photography has to accept the evidential language embedded in the medium.

-- Michael Hoppen Gallery website

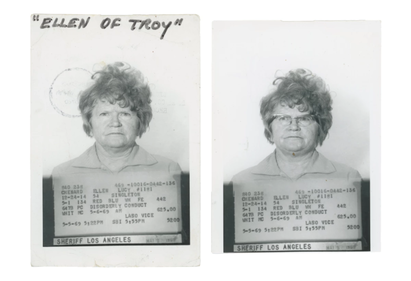

|

A group of police photographs and mug shots was also exhibited by the gallery. This type of image, pioneered by the French 'grandfather of forensics' Alphonse Bertillon, is an attempt to document the exact physical characteristics of a criminal suspect for later identification. Known as anthropometry, or the Bertillon System, this approach to photographic evidence was later superseded by fingerprint technology.

Collections of these mug shots from various periods can be seen online, for example: |

John Tagg, whose book 'The Burden of Representation' we referred to earlier, argued that the use of photography as a form of evidence in late nineteenth century culture was linked to the emergence of new institutions and practices of observation and record-keeping that were part of relatively new institutions - the police, prisons, asylums, hospitals, departments of public health, schools and the modern factory. These techniques of surveillance and documentation have had a direct impact on society, creating new types of knowledge and methods of control. We might pause to consider the amount of surveillance, record-keeping and evidence-finding that tends to dominate our lives in school these days. Photography, argues Tagg, was complicit in the "spreading network of power". Photographs enabled those in power to objectify others, putting them in their place and studying them like specimens. Central to this process was the assumption that photographs told the truth. However, as we came to realise:

Like the state, the camera is never neutral.

-- John Tagg

Some suggested activities:

- Visit your school library and select a variety of reference books featuring photographic illustrations. Try to make sure that you cover a range of subjects/disciplines. Re-photograph or photocopy your favourite examples. Curate an exhibition of these images removed from their original context. Decide whether or not to supply any textual information about them.

- Create your own fake police portraits. Investigate the visual language of these portraits - depth of field, lighting, composition, posture, clothing, props, accompanying text etc. How convincing can you make your mugshots? Can you add a further layer of (fake) authenticity by printing the image and adding additional marks/text to make it seem as though it has been kept in a police department file for a period of time?

- Take a look at Sandro Giordano's seres 'In Extremis' and Denis Darzacq's series 'The Fall'. Stage the 'evidence' of a dramatic accident. Try to create the image in camera without relying on Photoshop montage techniques. Decide the extent to which you will make your images convincing as 'evidence'. How do you want them to be read?

How little we seePhotographs can be a way to document the evidence of something that no longer exists. In Diana Matar's sequence 'Evidence', shown recently in the exhibition 'Conflict, Time, Photography' at Tate Modern, we see a series of buildings accompanied by text.

One of the key concerns of my work has been the attempt to photograph things that can no longer be seen. My interest in this paradox arises from a kind of intuition that the past remains, and that history’s traces are somehow imprinted on the spaces, buildings and landscapes where significant events have taken place. |

|

|

|

This film is about Sophie Ristelhueber's series 'Fait' from 1992. The French word means both done and made. Featuring 71 photographs taken of the site of the Gulf War, the desert of Kuwait, from both aerial and ground level perspectives, the series was inspired both by the TV footage of the war that appeared during the conflict and by Man Ray's 1920 photograph 'Dust Breeding'.

I wanted to do a statement on how little we see [...] The viewer, at a certain point, doesn't know if the image is taken 20cm from the ground or 100m above. The idea to bring this confusion about what we see. Is it big? Is it small? |

Both of these artists are interested in the traces of human activity on the landscape - what we leave behind in the form of marks or scars but also how photographs can be evidence that something significant has happened but is no longer present. They are dealing with particularly violent episodes, using photography to make sense of the seemingly senseless. Both artists are aware of the limitations of photography, of the troubled and contested relationship between a document and a work of art.

Suggested activities:

- Revisit the sites of your childhood experiences - the places you played, argued, got hurt, felt loved. Photograph these places, carefully selecting your point of view and composition. What will you include? What will you leave out? How will you present these images to the viewer? With or without accompanying text? In a grid or a linear sequence? In a book, slideshow or on the wall? What difference do these decisions make to the meaning of your images?

- Take a long walk with your camera. Notice the traces of human activity that the average passer-by might miss. Take pictures at very close range and from far away. Document the evidence of human presence but be careful to exclude people from your pictures.

- Photograph a building site from a number of angles, viewpoints. What evidence can you document of human activity in the landscape? You may wish to take a look at the work of photographers associated with the New Topographics.

Fabrications

In the 1970s artists began to really question the language and meanings of photographs. As photography was embraced by conceptual artists, new concerns emerged about the truthfulness of the photographic image. Several artist/photographers turned away from conventional documentary practice, troubled by ethical concerns. Staging photographs, often using actors, fabricating objects to be photographed and/or drawing attention to the inadequacy of photographic representations became ways out of this quandary. Much contemporary photographic practice is similarly concerned with issues of truthfulness. Here are some artist/photographers for whom photographs provide a way to test the 'evidence' before our eyes:

Thomas DemandThomas Demand trained as a sculptor and makes highly detailed three dimensional models out of card and paper which he then photographs. The motifs for his models are drawn from various sources of popular imagery. He always destroys the models once the photographs have been taken.

Suggested activity: Create your own 3D environment, either attempting to reproduce a scale model of something real or inventing a scenario. Photograph your model from a variety of angles. Which viewpoints are most successful? |

|

|

|

Nico KrijnoKrijno is a South African artist with a background in performance. For his photographic work he creates a variety of elaborate still life compositions, often using brightly coloured and patterned materials, which he then photographs before digitally transforming. He plays with our understanding about what a photograph can be, embracing the misuse of digital tools to both reveal and disguise the structures he photographs through cloning, healing, selecting, duplicating etc.

Suggested activity: Create your own still life from an assortment of objects. Combine unusual patterns, textures, forms, shapes etc. Transform these photographs with editing software, experimenting with the various tools at your disposal. |

Lucas Blalock is another artist who uses photography to ask questions about what we see. In this video he describes his process and some of the tools in Photoshop that he frequently uses (or misuses), drawing attention to the work usually done 'offstage':

Josef Schulz

|

Schulz photographs commercial buildings, the kinds of standardised storage units and warehouses that are found on industrial estates all over the world. Fellow photographer, Thomas Ruff, has written:

"Schulz starts by taking traditional photographs of the halls, storage facilities and industrial structures with large sized photographic plates. Using digital image processing, the analogue picture produced is then "cleansed" of the few remaining hints pointing to age, location or environment of the buildings [...] The viewer is somewhat confused: he seems to recognise parts that appear to be authentic without being able to distinguish whether they were truly located before the camera or generated with the tools of digital image processing. By doing so, Josef Schulz distances himself from the "objectivity" of photography and shows that pictures are always the construct of the visual power of imagination of the artist." Suggested activity: Take a series of photographs of branded objects or nearby shops/structures. Using digital editing software, attempt to remove any text or graphic marks, reducing the subjects to basic forms and colours. |

|