Each Threshold Concept has a supporting image inspired by our Photopedagogy camera. TC #9 presents the camera as a ballot box with opinions (or spoilt photographs) being cast.

Threshold Concept #9

Photographs are not neutral; they are susceptible to the abuse of power.

Photographs communicate powerful ideas about the world. They can be used to promote both good and bad attitudes. Therefore, students of photography must be very careful to think hard about what they see in other people's photographs and how they make their own. Who are you who will read these words and study these photographs, and through what cause, by what chance, and for what purpose, and by what right do you qualify to, and what will you do about it …? |

Photographs tend to start with an idea. This idea might be cultivated over time - collaborated upon, arranged, constructed and so on - or it might arise in the fraction of a moment, an instinctive thought to grab a particular slice of time, to frame in a certain way, to record in a particular tone. Either way, once in existence, a photograph has the potential to take on new meaning. This is something we looked at in TC#7. Photographs rarely sit on the fence. Even the most mundane and innocent of images arrive with strings attached. Desired or not, these strings attach to the past, to previous conventions, to technical limitations; to personal experiences. There are endless strands. Photographs are forever being pulled, sometimes with considerable power. One way or another, photographs are rarely neutral.

Powerful weapon, photography...

|

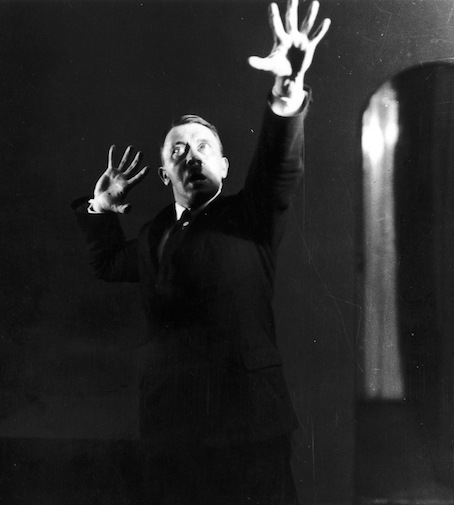

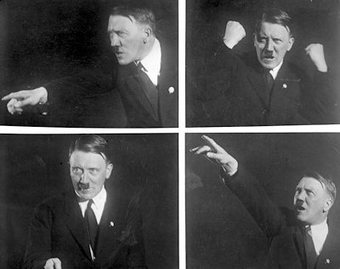

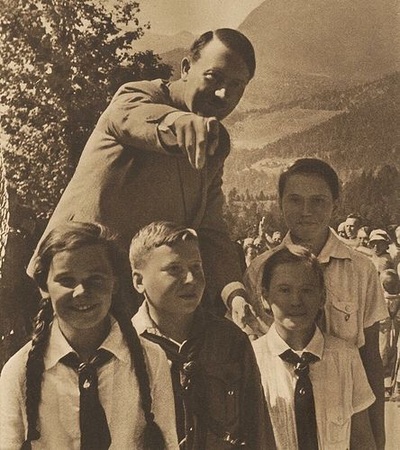

It could be Rule #1 in the handbook for tyrannical dictators: Photographs communicate powerful ideas about the world. It's a dictum that wasn't wasted on Adolf Hitler. On being appointed leader of the Nazi Party in 1921 Hitler named Heinrich Hoffmann as his official photographer, a post he then held for over 25 years. No other photographer was allowed so close. Hitler knew the importance of controlling his self-image and went to great lengths to do so. Aside from only releasing approved images, Hitler also used photography as a form of rehearsal and self-review. He insisted Hoffmann photographed him in new suits prior to public viewing and would regularly practice his highly animated speeches before the lens, reviewing gestures and expressions in obsessive preparation.

|

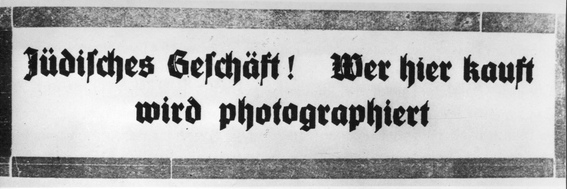

The camera was a weapon for intimidating Germans into compliance with or indifference to the persecution and humiliation of their Jewish neighbours. One popular sign announced during the boycott of April 1933: "Jewish business! Whoever buys here will be photographed!"

Source: Sybil Milton

|

With Joseph Goebbels appointed as Hitler's Minister for Propaganda in 1933, media outlets became tightly controlled and photographs - alongside film and radio broadcasts - became mediums for manipulation and indoctrination. Photography for the Nazi regime became another weapon with which to harass, humiliate and segregate, to devastating effect. |

The following text is taken from THE CAMERA AS WEAPON: DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE HOLOCAUST by Sybil Milton.

"The Nazis were aware that the camera could also be used as a weapon against them, and that images of the concentration camps would reveal the evils and horrors of political terror and racial fanaticism. After December 1944, Allied soldiers liberating France and Holland photographed identically worded French and Dutch signs posted near the Natzweiler-Struthof and Vught (Hertogenbosch) concentration camps: "Trespass of the camp grounds and taking photographs are absolutely prohibited. Violators will be shot without warning."

"The Nazis were aware that the camera could also be used as a weapon against them, and that images of the concentration camps would reveal the evils and horrors of political terror and racial fanaticism. After December 1944, Allied soldiers liberating France and Holland photographed identically worded French and Dutch signs posted near the Natzweiler-Struthof and Vught (Hertogenbosch) concentration camps: "Trespass of the camp grounds and taking photographs are absolutely prohibited. Violators will be shot without warning."

No photographs will be made of such abominable excesses and no report of them will be given in letters home. |

Milton later reflects on the contrast between the propaganda photographs taken by German photographers in comparison to those by independent photographers embedded within the Allied troops:

"Because they were intended as propaganda photos, the snapshots taken by the German photographers were often technically superior to the raw and powerful photos taken by the independent photographers embedded with the Allied troops. Robert Capa, Margaret Bourke-White, and Eugene Smith delivered few pictures of radiant heroes - instead they captured people who were suffering from the war. They didn't try to aggrandize the war and Capa, of course, is famous for the quote: "I hope to remain unemployed as a war photographer till the end of my life." |

Suggested activity:

Consider the images above taken by Heinrich Hoffmann and Hugo Jaeger, two photographers who were allowed unrivaled access to Hitler.

- What messages do each of these photographs project about Hitler and/or his regime?

- How might these images have been titled or captioned by opposing sides?

- Research the tragic fate of Joseph Goebbel's daughter, pictured above with Hitler. How does this information alter the emotional resonance of the image?

- Compare the images above with those below, taken by independent photographers who were embedded within the Allied forces. How do these images compare - technically, stylistically or in emotional resonance?

|

The discovery and liberation of the concentration camps by Allied forces produced some of the most powerful and disturbing images ever taken. A handful of these, such as 'Survivors at Buchenwald' by Margaret Bourke-White (above), have come to dominate the public visual narrative of events. These photographs - and subsequent ones to emerge, including unfathomable, macabre 'keepsake' albums taken by perpetrators themselves - were immediately deployed to share the full horror of events. Eventually used as evidence at military trials, these images remain key devices for educating future generations on the capacity of humankind to inflict suffering upon one another. |

There was an air of unreality about that April day in Weimar, a feeling to which I found myself stubbornly clinging. I kept telling myself that I would believe the indescribably horrible sight in the courtyard before me only when I had a chance to look at my own photographs. Using the camera was almost a relief; it interposed a slight barrier between myself and the white horror in front of me. |

Surface values...On the surface - and through being, literally, a surface (upon a surface) - the image to the left is curious rather than offensive. However, add context and the photograph resonates chillingly: The picture was taken within the main gas chamber at Auschwitz concentration camp and shows scratch marks upon the walls, possibly from human hands of various sizes, near to ceiling height and lower. Context conjures repulsion. The image was taken in 2004. Perhaps in being black and white - and following prior examples - you might have expected it to be from an earlier period, a form of evidence in the immediate aftermath of liberation.

Steve Ellis, history teacher and experienced Auschwitz guide, offers further context: "It is very problematic to be certain that the scratches in this photograph were made by dying victims. Panic and agonized attempts to escape the gas make it a possibility. However, there are a number of balancing factors to consider: |

- This chamber was originally a morgue, then temporarily a gas chamber and following this, it was also used as an execution site and, finally, it was used as an air raid shelter by the Auschwitz guards

- The present chamber also underwent partial reconstruction after the war before the camp was opened as a memorial site

- It has been re-painted at least once

- Visitors were also not always as closely supervised as they are now. Indeed, it is also no longer permitted to take photographs in the chamber.

In short, there could be a number of plausible explanations for these marks existing which have nothing to do with the process of gassing. The photograph needs close interpretation in its historical context. In order to accept the marks as the scratches of dying victims something more substantial than supposition is needed. The scratches in the photograph appear higher up the chamber wall. Testimonies tell us that often children were found higher up, presumably raised by adults (the children would not always have had a parent with them). Survivors might be able to corroborate the scratches as genuine marks from victims. I'm simply aware that I have not seen a definitive account."

In questioning the photograph above, the intention is not to cast doubt on the atrocities committed but rather to emphasise the ambiguity of photography and the potential for an abstract image to encourage us towards a conclusion in line with our expectations. As TC#9 reminds: Students of photography must be very careful to think hard about what they see in other people's photographs.

The following section shares two photographs that provoked various levels of outrage when first published. In both cases those depicted came forward to give their side of the story, accusing the photographer of misleading the public...

The cold-hearted eye...

|

The image to the right, winner of the World Press Photo 2006, was taken by Spencer Platt, an American reportage photographer. It was shot in Lebanon on 15 August, a day after a ceasefire in the southern suburbs of Beirut.

The original caption accompanying the picture read: "Affluent Lebanese drive down the street to look at a destroyed neighbourhood, 15 August 2006 in southern Beirut, Lebanon." On publication the image (and caption combined) immediately divided opinion and caused much controversy. Many felt that the photograph depicting self-centered youth enjoying a spot of 'disaster tourism', represented much of what is wrong with youth culture, in Lebanon and beyond. The car passengers were initially vilified and as a result were motivated to tell their side of events, of which you can read more here. Interestingly, the accounts of the passengers do not entirely disagree with the presumptions made, but they do add context that complicates our reading of the shot. The picture challenges our notion of what a victim is meant to look like. These people are not victims, they look strong, they're full of youth. |

The media's the most powerful entity on earth. They have the power to make the innocent guilty and to make the guilty innocent, and that's power. |

|

Thomas Hoepker's photograph of young people on the Brooklyn waterfront, back-dropped by the twin towers attack, is another image which provoked widespread vilification. However, unlike above, it was not an immediate, timely outpouring of anger - this relaxed, seemingly ambivalent response to events was not shown until 5 years after the attack, displayed within an anniversary publication. Nethertheless, outrage quickly followed, targeted once more at the capacity of young people to remain so detached as to be able to - quite literally - turn their backs on their own country in turmoil. As with the Spencer Platt image taken in Beirut, those depicted found themselves moved to defend their actions - to add new perspectives which subsequently complicate our reading of the image.

This article by art critic, Jonathan Jones, provides further reading and links to testimonies. He also places Hoepker's photo within broader contexts, emphasising that artists and writers have regularly captured the 'dissonance' of significant historical moments - when life does not simply stop dead but ticks over in unpredictable and ever-complicated ways. |

We were in a profound state of shock and disbelief, like everyone else we encountered that day. Thomas Hoepker did not ask permission to photograph us nor did he make any attempt to ascertain our state of mind. [...] Had Hoepker walked fifty feet over to introduce himself he would have discovered a bunch of New Yorkers in the middle of an animated discussion. A more honest conclusion might start by acknowledging just how easily a photograph can be manipulated, especially in the advancement of one's own biases or in the service of one's own career.

-- Walter Sipser (pictured far right)

|

In this video Thomas Hoepker shares his thoughts on this iconic photograph and explains how, at the time of taking, it held little significance to him. He also discusses the difference between being an art photographer (who might stage a picture) to a news photographer (who shoots what is in front of him). This raises some interesting issues about photography's problematic relationship to evidence and the truth. |

Suggested activity:

The photographs above by Spencer Platt and Thomas Hoepker only provide us with a fragment of visual evidence from two particular moments in time. This 'evidence' has proven to not be fully reliable.

How would our understanding of the image change should we be able to hear a recording of the conversations taking place at this time?

How would our understanding of the image change should we be able to hear a recording of the conversations taking place at this time?

- Scrutinise the individuals at the forefront of these images. What might they have actually been saying? Follow the links provided to gather their personal insights and then, in small groups, develop a script - recording even - to accompany the photograph.

- Alongside this, produce a parallel recording of the conversations imagined by the outraged viewers.

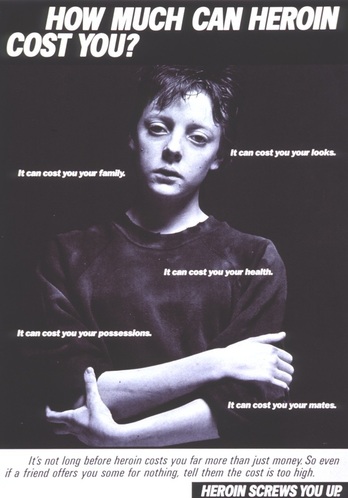

Photography has the potential to promote both good and bad attitudes. The following section considers the power and unpredictability of photography when employed for advertising purposes...

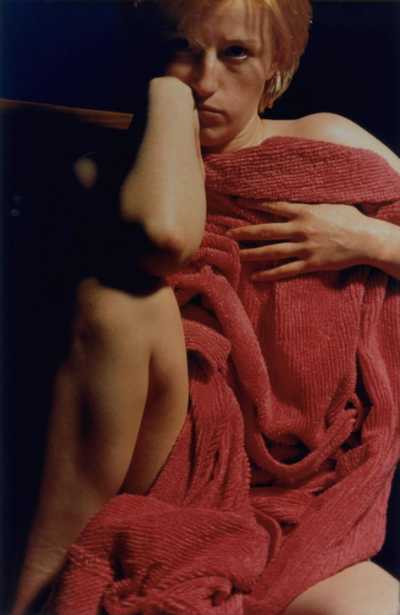

Photography screws you up

In the mid-1980s, the Government responded to a surge in heroin use with a poster campaign featuring a wasted youth with the caption: "Heroin screws you up". Dozens of posters went missing as the youth became a teenage pin-up. Within months "heroin chic" appeared on the catwalks. It's not too hard to imagine yourself in the eye of the brainstorm: It's the 1980s, a time when advertising agencies ruled the world. A hard hitting campaign is required, commissioned by the Department for Health to address growing concerns of wide-spread heroin use. But fear not; Advertising, Generation X's most streetwise of uncles can surely save the day...

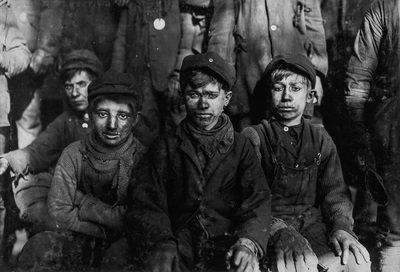

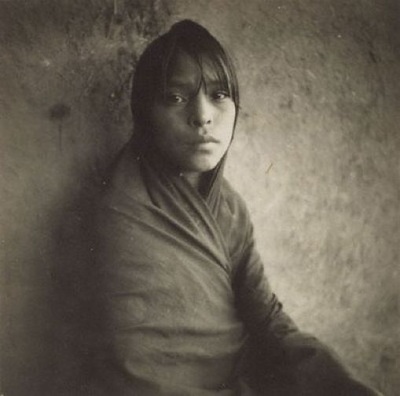

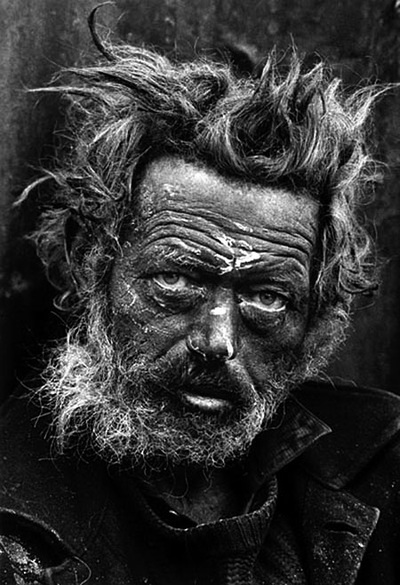

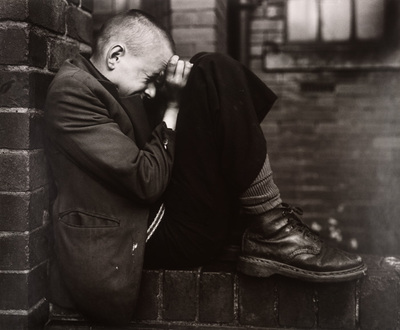

*Cut to agency boardroom; filofaxes and mobile brick-phones abound, thoughts of a Yellow Pencil are in the air. One ego pipes up, all braces and bright-rimmed specs...* "I'm telling ya Maurice, gritty, black and white portraits; touch of social documentary. Y'know, 'McCullin' style. Hardship, torment, staring right down the lens; it'll be a winner." 'Heroin screws you up' eventually unfolded, but not as intended. The campaign is widely considered to have contributed to an increase in substance abuse in the 1980s. The photographs, commissioned to whisper of social hardships - seemingly in the tone of Hine, Lange, McCullin or Chris Killip - spoke instead in more unexpected ways. The black and white photographs were perceived (at least by some) as glamorous - angsty portraits, not disimilar to posters of rock idols pinned up in bedrooms across the land. 'Heroin screws you up' returned a powerful message rather than sending one out: Use photography at your peril, it doesn't always inject what you prescribe. |

Suggested activity:

The portraits above might all be considered forms of 'social documentary'. The poor, social outcasts and lower classes have been reoccurring themes throughout the history of photography, a desire for political and social change often being the motivation for a photographer (or commissioning editor).

- How effective are these photos in portraying hardship?

- Which photographs (if any) appeal to you the most - and if so what do they ask of you?

- Three of the four images above rely on eye contact to connect with the viewer. Is this significant? How does this compare to the 'Heroin screws you up' poster which uses an actor directly staring at the camera / viewer - is it possible to distinguish between a staged or genuine stare?

- TC#6 explored how the adding of captions to a photograph can distort our understanding of it. How important are the titles to these works above? How might an advertising agency exploit these images to positive effect? Research the images and create accompanying text that sensitively sheds more light on the subjects.

Fashion, victims...

|

If Photography, in all its guises, was to ever find itself before judge and jury, 'Fashion', would be quickly singled out and shuffled to the front, first up for condemnation. No other genre has been so antagonistic, kicking at the boundaries of morality and taste. Fashion photography has steadily worked its way under our skin since early 20th century, regularly provoking outrage in a continual quest to be heard in new ways.

Regarding TC#9 and abuses of power, fashion photography takes the biscuit, then throws it back up in our face. It's a seductive genre that demands our attention, carrying significant sway with young people whilst piling pressures upon them. Any photography teacher working with young people knows this already - Just set a task to do a fashion shoot and observe carefully: self-consciousness, preconceptions, concerns about body image, learned behaviours all arise quickly. Not pretty. But that said, fashion photography is by no means an all-out-evil. It does provide a complex and compelling narrative, woven across the histories of photography and art. Also – for better and worse – it can hold a telling mirror up to society itself, which really is worth a look. |

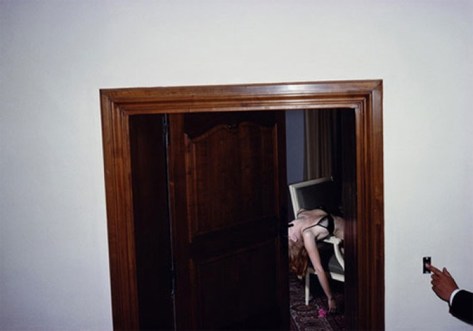

Guy Bourdin makes for a particularly fascinating study within the context of TC#9. He is a photographer notorious for being volatile and controlling, whose models often appeared as victims in violent or compromising positions. In his photographs he retains the power, objectifying the model; neglecting the product; breaking conventions.

Bourdin's pictures were the epitome of what the surrealists called 'convulsive beauty' (of which more can be read here). He refused to have his work shown in galleries or books insisting that it remained in the magazines for which it was commissioned, often published across double-page spreads. Within one criticised 1978 Vogue edition, the legs of a female model were printed either side of the page leaving the reader to open and close them. Always contentious, Bourdin established the idea that the product is secondary to the image, carefully constructing surreal and visually striking scenes that - depending on your viewpoint - have retained the capacity to shock, amuse, baffle or delight, often within the same moment.

Bourdin's pictures were the epitome of what the surrealists called 'convulsive beauty' (of which more can be read here). He refused to have his work shown in galleries or books insisting that it remained in the magazines for which it was commissioned, often published across double-page spreads. Within one criticised 1978 Vogue edition, the legs of a female model were printed either side of the page leaving the reader to open and close them. Always contentious, Bourdin established the idea that the product is secondary to the image, carefully constructing surreal and visually striking scenes that - depending on your viewpoint - have retained the capacity to shock, amuse, baffle or delight, often within the same moment.

Fear is something that we, despite ourselves, want to experience. And I think the violence does add glamour in a kind of perverse way.

-- Nick Knight

Bourdin realised that it is not fashion itself that seduces people but the fantasy it represents. Psychodrama and the theatre of the absurd pervade his work; a true master of the storyboard, Bourdin rigorously planned his compositions for fashion shoots to suit the format of the printed page. Conceived long before the advent of digital retouching, he went to tremendous lengths to produce highly stylised images, often pushing his models to their limits to achieve his desired vision.

Source

Suggested activities:

Who holds the power? Consider the images above by Guy Bourdin within the context of TC#9: Photographs communicate powerful ideas about the world. They can be used to promote both good and bad attitudes.

- What message do these images communicate - both individually and collectively? And who is ultimately responsible for this - the commissioning fashion label, the photographer, and/or the model, or the publisher? Do fashion photographers - or the editors who approve their images - have any moral responsibilities to their audience? What, if any, are the dangers of misuse of power?

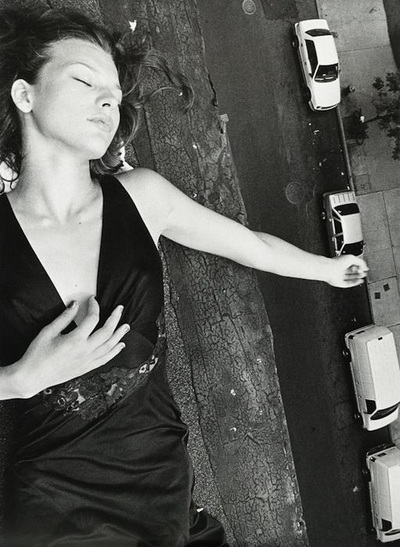

- Compare Bourdin's work to the 'Heroin chic' examples that follow. Consider the differences in style and technique and how this might influence what is communicated.

Smacks of trouble...

In his book, Photography - a highly recommended read - Stephen Bull offers a chapter packed full of insights into the complexities of fashion photography and its continual quest to reinvent itself.

Fashion, by definition and in order to exist commercially, must always be 'new'; yet it is also constantly recycling, drawing on the past for ideas.

-- Stephen Bull

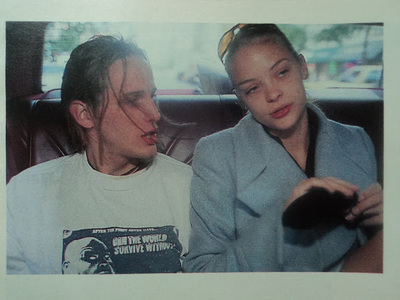

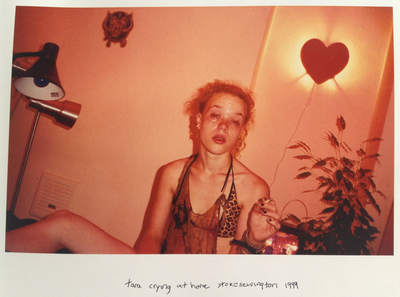

This amalgamation of influences is evident in the emergence of 'Heroin chic' in the 1990s, arguably fashion photography at its most abusive. Bull identifies the coming together of the rave (and drug) culture of the 1980s; the partial revival of punk subculture (in the form of 'grunge'); and an increasingly raw, snapshot style approach to documentary (evident in the work of Nan Goldin, for example). High profile films such as Trainspotting and Pulp Fiction probably injected their own influences too. Whatever, Heroin chic's abject 'realism' and use of thin, likely-to-be anorexic models left a bad taste for many, one that still lingers around the fashion industry today.

The grunge aesthetic of the early 1990s, with its use of the visual codes of snapshot and documentary photography, suggests that it shows real people and real-life situations. However, most commentators on this form of fashion photography are careful to place the word 'real' in quotes to warn that what we see is not reality, regardless of how the pictures appear.

-- Stephen Bull

Suggested activities:

- Collect a range of magazines and newspapers that include fashion photography and advertising. Challenge students to order these under a range of headings, repeating the exercise with increasing complexity. For example, you might use the following headings / stages to consider where the 'power' of the image lies:

- Shape, Texture, Colour, Tone, Form

- Informative, Stylised, Abstracted

- Staged, 'Real' / Fiction, Fact / Manipulated, Truth

- (The image draws most attention to:) The model, The clothes, The words, The story, The Photographer, Ourselves

- The past, The present, The future

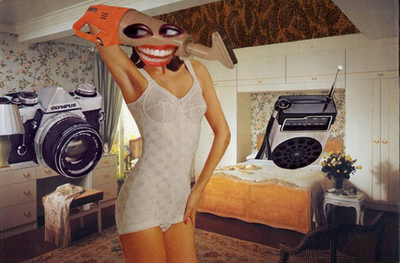

- Experiment with 'disrupting' fashion adverts by adding text, questions, quotes, doodling or collaging (refer to the next section for further insights on this). How might you enhance, contradict or challenge the intentions of an image?

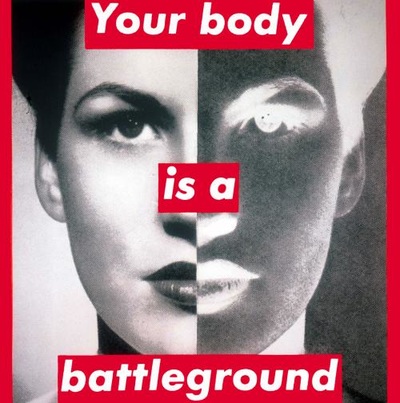

Balancing scales, challenging stereotypes...

|

Back in 1972, John Berger made a TV series (and book) called 'Ways of Seeing'. Episode 2 (Chapter 3 of the book) deals with the representation of women in art. Coinciding with feminism and a growing sense of injustice felt by women about ingrained sexist attitudes in society, Berger's observations made for compelling viewing:

Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object - and most particularly an object of vision: a sight. |

Precisely because photography is such a powerful way to transmit messages, (imagine advertising without the photographic image) photographs can be used to challenge stereotypes and argue for social justice. They can be a kind of positive propaganda. The visual language of advertising, marketing and fashion, even of painting and film, can be used to subvert power relations and ask some difficult questions. The viewer is momentarily seduced by what seems to be visually familiar - bold colours, beautiful bodies, opulent surfaces - but is subsequently challenged by complex messages that seek to undermine lazy assumptions or conventional ways of thinking. For most of its history, art has presented women as passive objects to be looked at by male painters and viewers. Photography has largely maintained this tradition, with a few notable exceptions. But what happens when women become makers of meaning? Women photographers have chosen to use photography to directly challenge sexism, to question the assumed authority of the male gaze and establish other ways of seeing.

In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy on to the female form which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.

-- Laura Mulvey, Visual And Other Pleasures

You may want to research the ways in which photography has been used by other groups in society to question the status quo, challenge assumptions and overcome prejudice and inequality.

Suggested activities:

- Make a list of issues you care about. These could be on a huge scale (global warming, poverty, racism) or more personal issues that relate to your own experience. Do you have any existing photographic associations with these issues? Choose one issue from your list. What images immediately come to mind when you think about it?

- Now, imagine you have been asked to create some photographs to tackle one of these issues. What subjects would be appropriate? How would you create the photographs - staged or candid, street or studio?

- Create at least two different ways to present your chosen issue. Think carefully about the messages conveyed by your images - how will they be read by different viewers? Will you supply any text or leave them open to interpretation? Will you trust the viewer to see what you intended? Will you supply straight photographs or manipulate them in some way? Show your pictures to various people and note down their reactions. How easy/difficult is it to make photographs with a clear meaning? What have you learned about photography from this exercise?

Further reading:

The following texts offer further insights into some of the ideas that might have been scratched at the surface here:

TC#9 on Pinterest

Links referred to in this article and others besides are included in this TC#9 Pinterest board. We'll keep adding to these as we discover new resources.

Please use the comment boxes below to share any feedback or thoughts that you might have. |

By Chris Francis and Jon Nicholls