|

Teacher Resources

A summary of some of the key discussion points and classroom activities from this web resource is available to download here.

|

These resources have been developed in partnership with The Royal Photographic Society (RPS) in support of Sugar Paper Theories by Jack Latham which was shown at RPS Bristol from October 2019 to January 2020. This resource has been devised for KS4-5 visual arts students but could easily be adapted for a younger audience and across the curriculum. You can take a virtual tour of the exhibition to see how the images and artefacts were installed in the space.

| ||||||

The Royal Photographic Society exists to educate members of the public by increasing their knowledge and understanding of Photography, and in doing so to promote the highest standards of achievement in Photography. Click here to discover more.

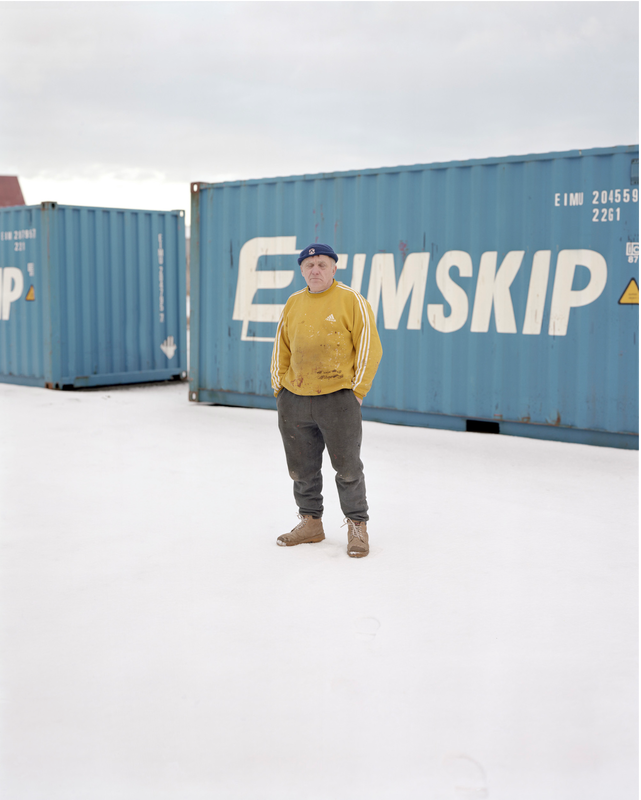

Sugar Paper Theories: A Grey AreaJack Latham is a contemporary photographer who produces original imagery and utilises existing work to tell complex stories. Sugar Paper Theories is his second major project, developed in response to a notorious unresolved double murder investigation in Iceland. The work won the Bar Tur Photobook Award in 2016 which enabled publication with Here Press and The Photographers' Gallery. The resulting photobook is an innovative combination of original and archive images and text.

The facts of the case are bizarre: Forty years ago, two men went missing in southwest Iceland. The facts of their disappearances are scarce, and often mundane. An 18-year-old set off from a nightclub, drunk, on a 10-kilometre walk home in the depths of Icelandic winter. Some months later, a family man failed to return from a meeting with a mysterious stranger. In another time or place, they might have been logged as missing persons and forgotten by all but family and friends. Instead, the Gudmundur and Geirfinnur case became the biggest and most controversial murder investigation in Icelandic history This video interview with Jack Latham helps to explain the circumstances of the case and the photobook that resulted from the work he made in Iceland:

|

|

|

To consider

For discussion

|

Sugar Paper Theories is a type of document. It refers to events from the past and uses a documentary style of photography to capture events, places and people in the present. The photobook and exhibition are also works of art, expressing the interests of the artist/photographer through aesthetic decisions. There is often a tension between the documentary and the artistic. Issues of truthfulness and the role of artistic license are hotly debated. There is a strong tradition of documentary practice in photography and yet, in recent times, we have begun to be more suspicious of photography's ability to represent reality. In some ways, Sugar Paper Theories is about the very notion of documentary uncertainty.

While the notion of a document is historically tied to ideas of certitude and confirmation and is primarily used in the legal realm, this certitude has all but vanished from contemporary consciousness. The experiences of the 20th century, its large-scale enterprises of propaganda and disinformation, have created an attitude, which could be called habitual distrust as well as advanced media literacy. Documentary modes still appeal to institutional modes of power/knowledge and cite their authority, but the effect is rather a perpetual doubt; a blurred and agitated documentary uncertainty..."

-- Maria Lind and Hito Steyerl, ‘The Greenroom: Reconsidering the documentary and contemporary art’.

Further resources

- Listen to a fascinating BBC radio broadcast about the Reykjavik Confessions here.

- Out of Thin Air, a documentary film, directed by Dylan Howitt, 2017

- Deep down, I knew it didn't happen...; newspaper article, Paula Cocozza, 2017

Part 1: The (Mis)Remembrance of Things Past

Sugar Paper Theories contains a number of old photographs from police archives. Given that the original investigation took place in the 1970s, Latham has included these images to help tell the story of what happened then and how these events have reverberated down the years. Photographs have a very special relationship to time (see Threshold Concept #10 below). In 1859, some 20 years after the 'invention' of photography, the poet Oliver Wendell Holmes referred to photography as "the mirror with a memory". When we remember something, it's almost as if we were taking a mental photograph. We place an unusual amount of trust in photographs as sources of evidence. Perhaps this is because they appear to simply copy observable reality and create a visual facsimile of a fraction of a moment in time. However, photographs are much stranger than this. The world is not flat. It doesn't have an edge. Photographs present us with the illusion of reality but, in fact, they are highly artificial, even those that don't look so at first glance. Perhaps our memories and photographs are equally unreliable?

Memory does not make films. It makes photographs.

-- Milan Kundera

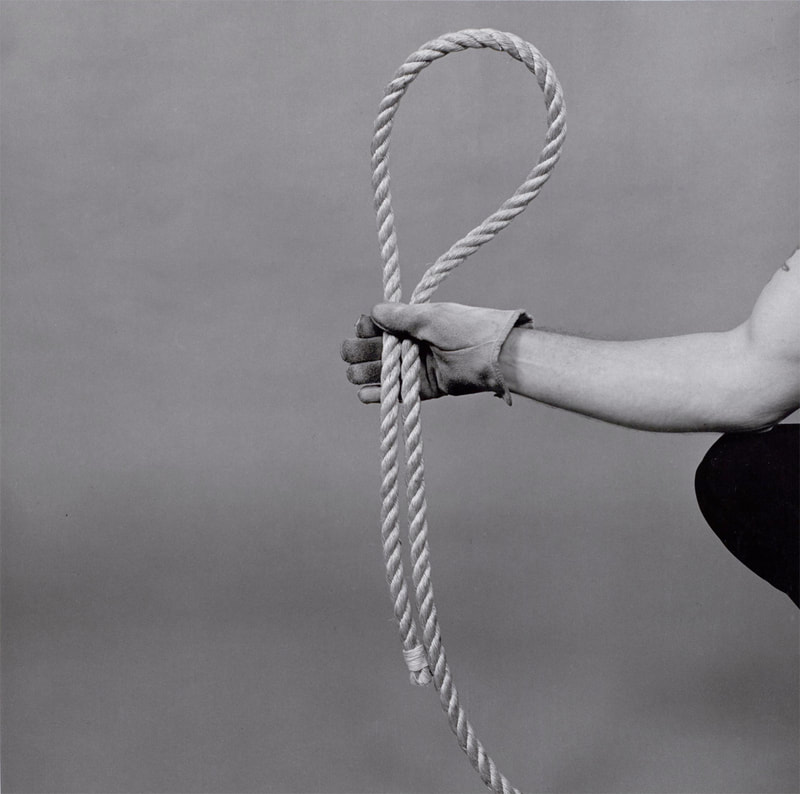

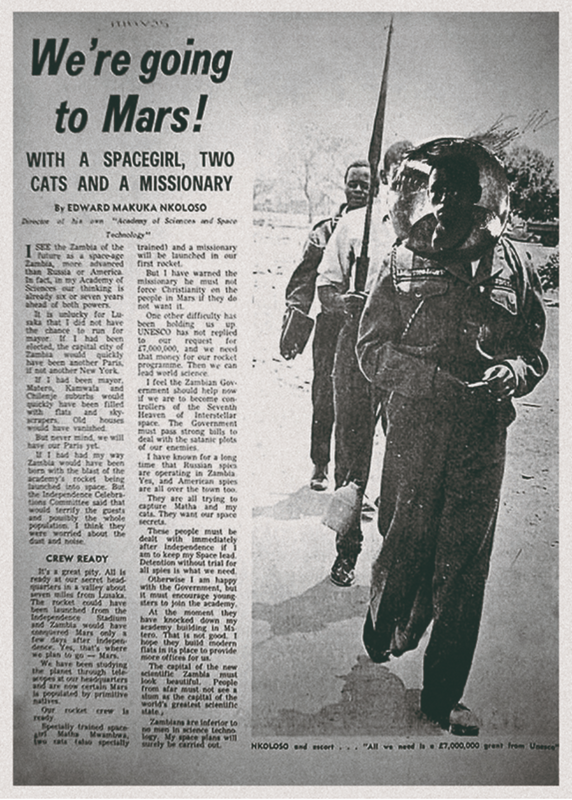

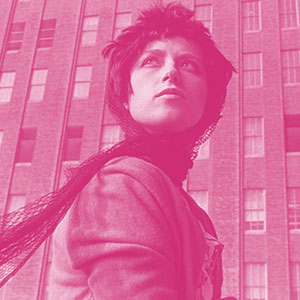

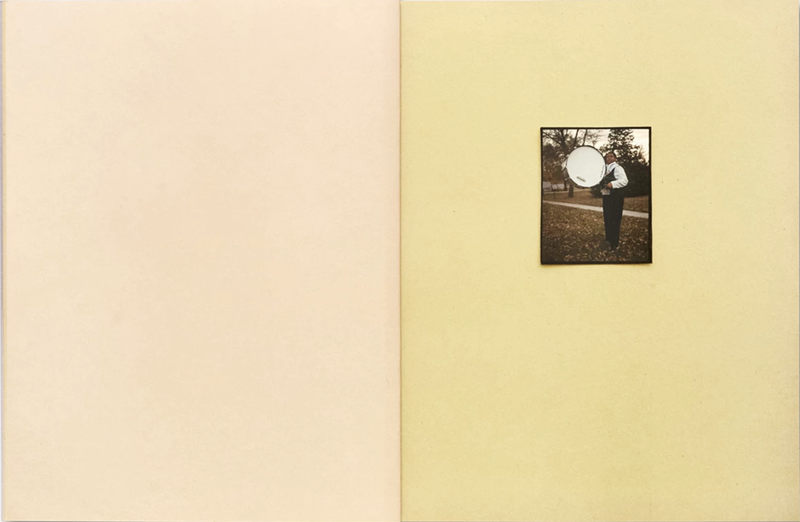

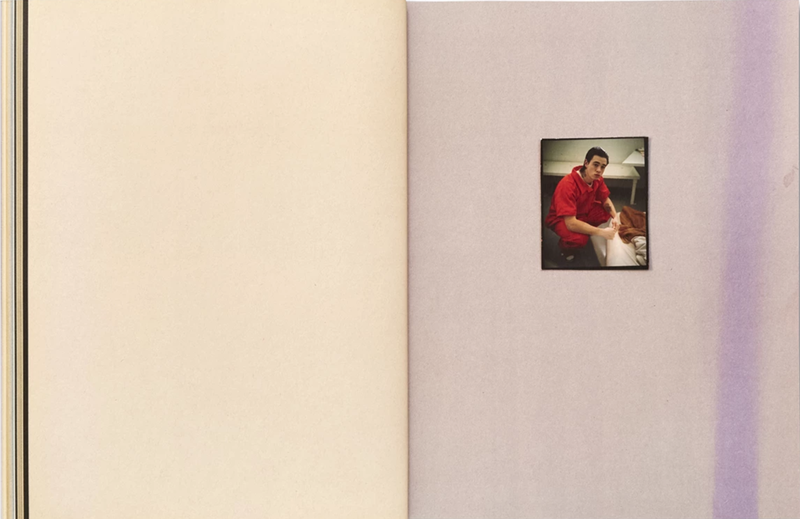

Here are some of the archive pictures from Sugar Paper Theories:

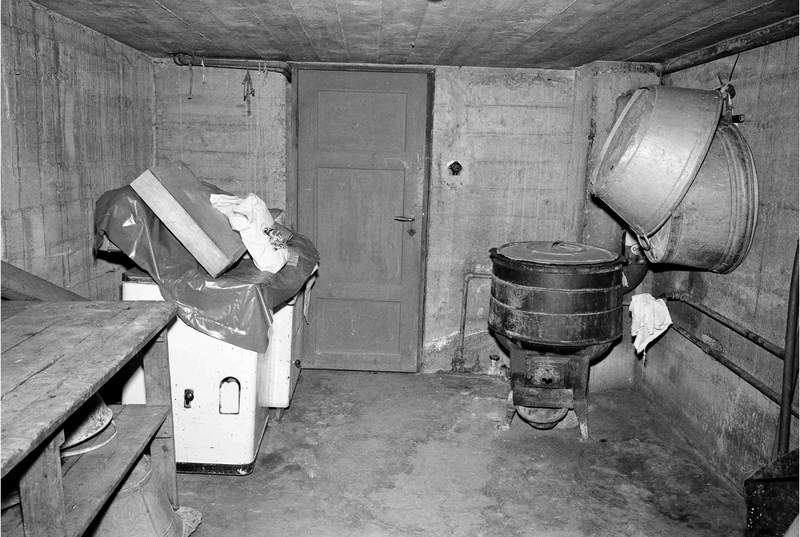

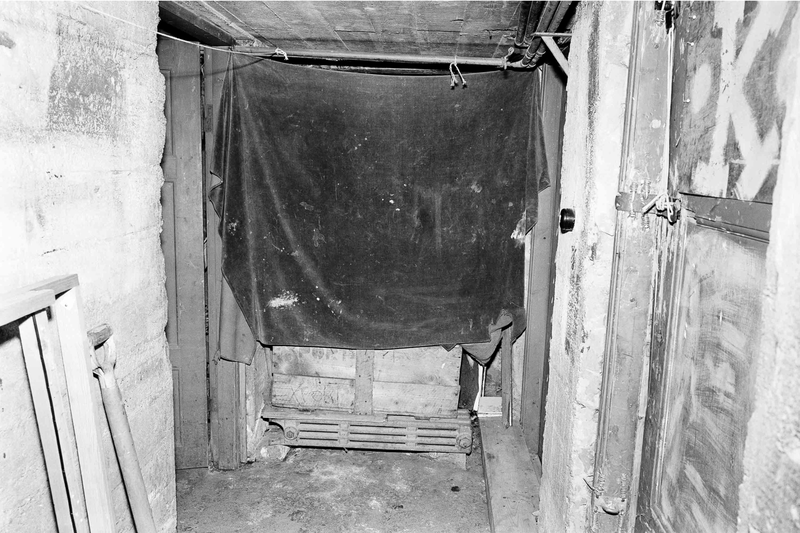

These images were made by the police to document aspects of the original criminal investigation. However, with the passing of time, they can now be seen differently. We might be drawn to their aesthetic qualities, their ability to suggest a particular atmosphere, the way that light plays across the various surfaces. We might wonder about the identities of the people in the group portrait and who lives and works in the buildings. The two bunker-like rooms might evoke a range of feelings - claustrophobia, fear, intrigue etc. Interspersed throughout the book (and exhibition), these photographs are far from being direct and reliable sources of evidence. Each viewer might see something different in them, feel differently about them. Latham calls into question the relationship between memory and truth. This is further reflected in his interest in conspiracy theories, something that recurs in his more recent project Parliament of Owls.

The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.

-- from 'The Go-Between' by L. P. Hartley

For discussion

- Why might a contemporary photographer be interested in photographs from the past, taken by someone else?

- How are photographs used as forms of proof? Why is this? How reliable are photographic documents?

- Is it possible to take a photograph objectively?

- What can historical photographs tell us about the past? What can't they tell us?

- Jack Latham refers to his interest in the "grey area", a space of contradictions, mysteries and insecurities. How can photographs help us to explore things we can't quite see or understand?

Threshold Concept #10: A reminder of things lostOur Threshold Concepts for Photography aim to expose some of the 'big ideas' in photography education. Threshold Concept #10 reminds us that photographs are memento mori - reminders of death. Each photograph contains a parcel of time that has disappeared and can never be lived again. Even the language of photography reflects this connection to violence and mortality - we might 'aim' our cameras in order to 'shoot' or 'capture' a 'still' photograph, before 'hanging' it on a wall. Have you ever had the experience of remembering something that you think happened to you, only to realise later that what you are remembering is a photograph? We take so many photographs nowadays that it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between a 'real' memory and the recollection of an image.

Of all the means of expression, photography is the only one that fixes a precise moment in time. We play with subjects that disappear; and when they’re gone, it’s impossible to bring them back to life. |

Although Jack Latham does not attempt to pass off the archive photographs in Sugar Paper Theories as his own work, the use (appropriation is the technical term) of other people's photographs is a feature of many artists' practice. Unlike paintings, photographs can be reprinted almost endlessly. They are designed to be copies (rather than unique originals). They can be acquired fairly cheaply. Their contexts can be altered, as can the physical prints. These possibilities have appealed to many artists, and continue to do so. Each time a photograph is used in these ways, the viewer is confronted with a reminder of lost time. The past comes back to life, but it's not the same.

Consider the following examples:

Consider the following examples:

Activities

- Experiment with a series of old photographs (not taken by you). These could come from a family album, magazines, eBay, library books or charity shops. Try to find a variety of types (genres) of photography e.g. landscapes, architecture, portraits, still life etc. Make copies of these images (black and white photocopies would do). Try arranging them in different sequences to tell a range of stories. Share these sequences of pictures with a range of people and ask them to tell you a story about them. You may decide to capture these stories in words, video or audio recordings.

- Discreetly remove a photograph that is on display in your home. Ideally, choose a photograph that contains some of the family members that you live with. Next, individually question family members about the contents of the photograph - the people, location, time etc. but also ask for specific secondary details, for example clothing worn, colours, background details, positioning, who took the photograph etc. Compare accounts and identify differences. Is it possible to manipulate a copy of the photograph to align with mistaken memories?

- Find an old family photograph featuring several individuals. Either, (a) interview all the surviving subjects in the photograph, asking them to remember the occasion in as much detail as possible - what happened, how did they feel before, during and after the photograph was taken, what was their life like then?...etc. OR (b) invent a series of short stories/descriptions in which you imagine the lives of each of the subjects in the photograph.

- Find a photograph of you as a younger person. If it's a digital image, make a print of it. Now, try to re-stage the photograph as carefully as possible. Consider the setting, your posture, the props and clothes, your expression etc. You may need to collaborate with a friend. How close to the original photograph is your new image? Display them side-by-side.

- Select a news story from a newspaper, magazine or website (preferably one that is new to you). Create a series of photographs to illustrate the story. Think carefully about how many pictures you might need, what types (genres) of photograph you will create, how you will combine the images, what captions you might use etc. Decide which details of the story are most significant. You could take a literal approach (making documentary style photographs), or you might decide to try something more imaginative, poetic and allusive.

Does a photograph really enable us to remember a person as he really was, or an event as it actually happened? Does the sight of someone bring back the sound of her voice, her smell, the way she walked? Can a photograph of a childhood holiday ever bring back the sensation of warm sand slipping between our toes? Images can stimulate memories but memories are not images. They are sensations. As such, they cannot be encompassed within the boundaries of visual representation—photographic or not.

-- from Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance

Wider reading

Related PhotoPedagogy resource:

|

Believable Fictions The relationship between photographs and reality is complex. Photographs can appear to be copies (facsimiles) of the world. It is tempting to think of them as factual evidence that something happened or existed, but that is not always the case. This resource looks at ways artists have deliberately misled, playing upon our expectations of photography. |

Part 2: Crime and Punishment

With the invention of the camera, society gained an effective tool for law enforcement—a seemingly infallible way of identifying criminals and garnering evidence. In fighting crime, the notion of truth is imperative, so we put photographs to work as a way of determining the actions and identities of perpetrators, though sometimes such judgments prove to be inaccurate. Furthermore, with its special capacity for implication and dissemination, photography gives us voyeuristic entry to traumatic events, usually after they have occurred. This unique access affects dramatically how we record and remember violent and unlawful acts, fuelling both our outrage—and our fascination.

-- Karen Irvine, Curator of 'Crime Unseen', The Museum of Contemporary Photography, 2012

The history of photography is closely connected to industrial society's need for reliable data, surveillance and control. Photographs clearly played an important role in the the Icelandic police investigation of the Gudmundur and Geirfinnur case. Crime scenes were documented, re-enactments staged and photographed. The collection of evidence and the taking of photographs were seemingly synonymous. It seems likely that the re-staging of crime scenes, documented with photographs, contributed to the false memory syndrome experienced by the victims. Photographs are extraordinarily persuasive.

Photographs furnish evidence. Something we hear about, but doubt, seems proven when we're shown a photograph of it. In one version of its utility, the camera record incriminates. Starting with their use by the Paris police in the murderous roundup of Communards in June 1871, photographs became a useful tool of modern states in the surveillance and control of their increasingly mobile populations. In another version of its utility, the camera record justifies. A photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened. The picture may distort; but there is always a presumption that something exists, or did exist, which is like what's in the picture.

-- Susan Sontag, On Photography

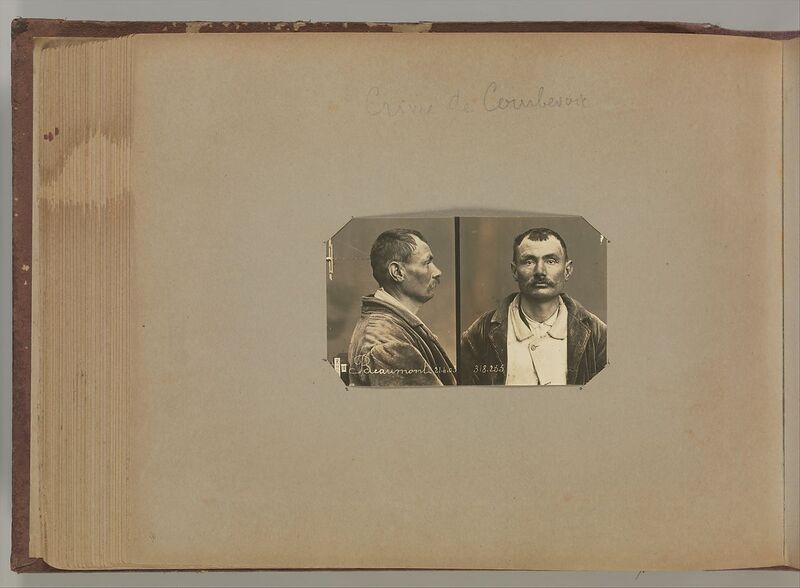

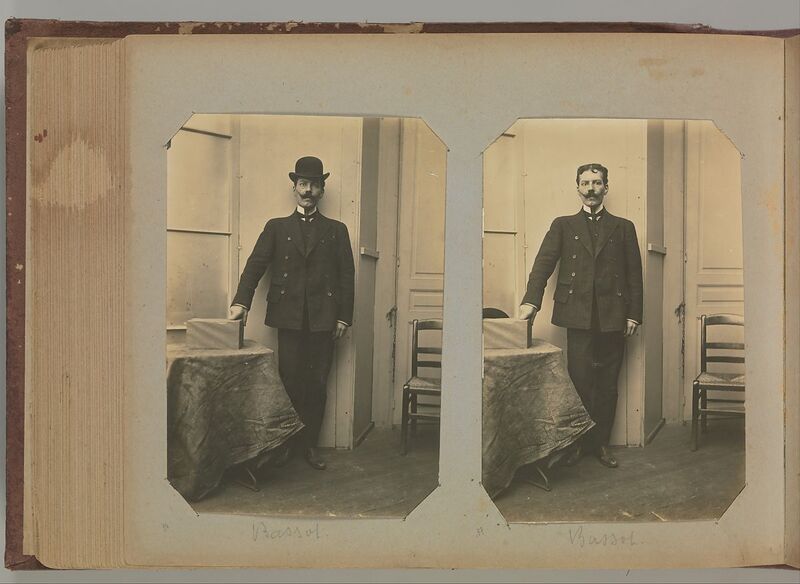

This link between photography and its use by police forces can be traced back a long time. Accurate identification of repeat offenders became a real issue in late 19th century Paris and Alphonse Bertillon is credited with inventing a system of identification that included what we now know as the 'mugshot' to help solve the problem.

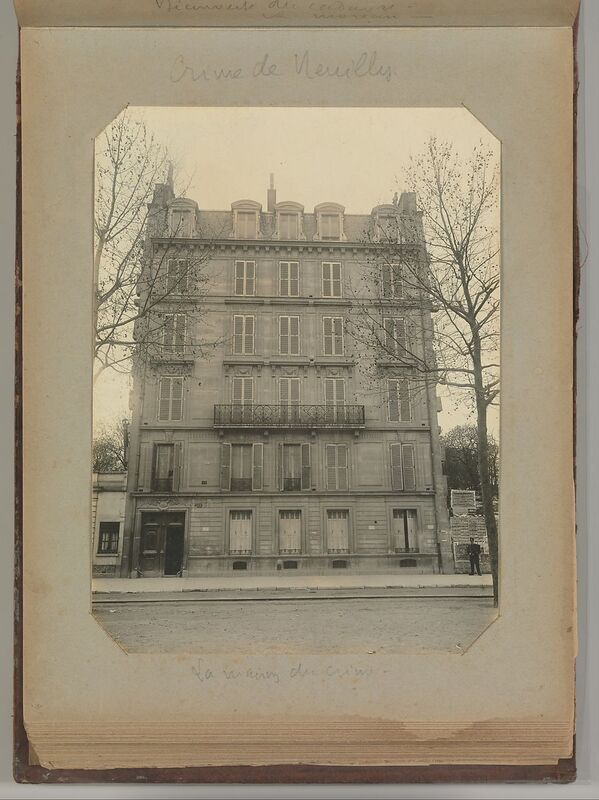

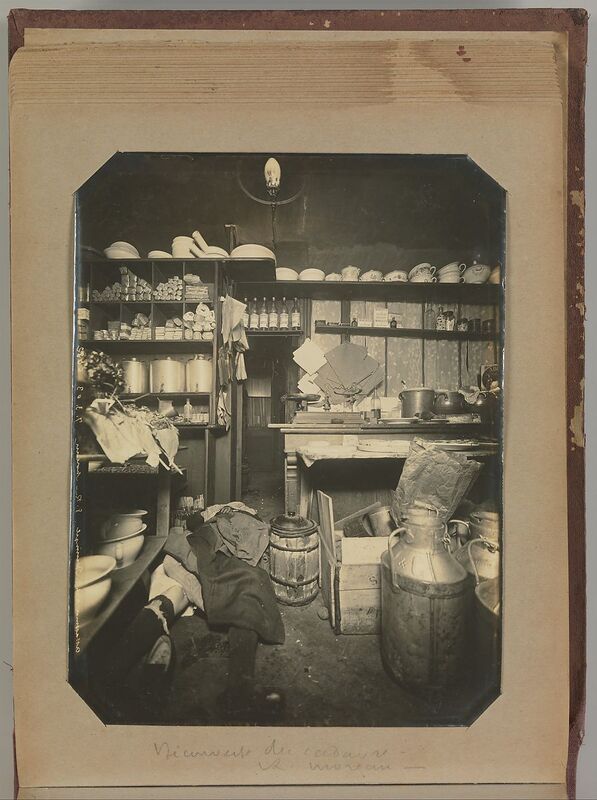

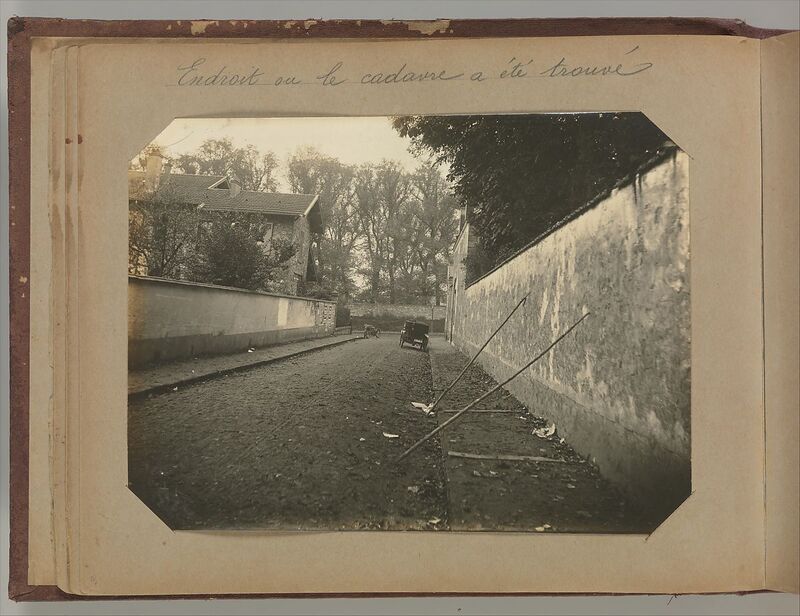

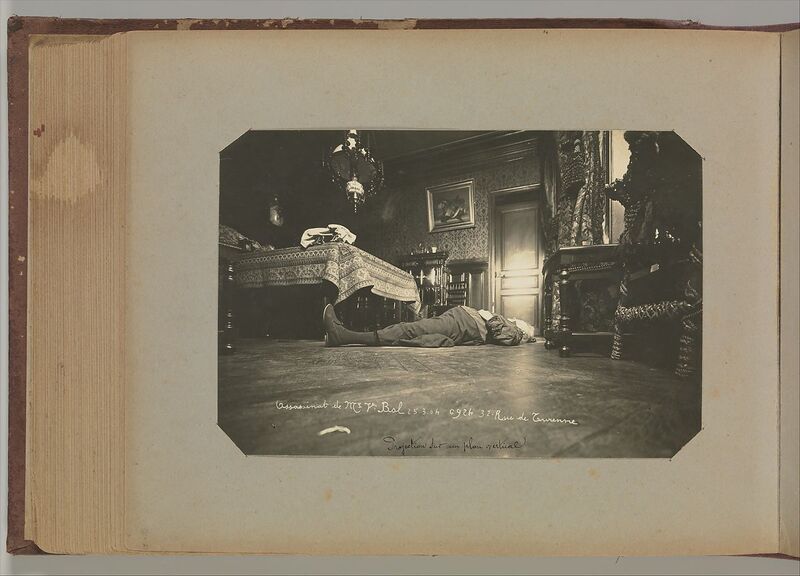

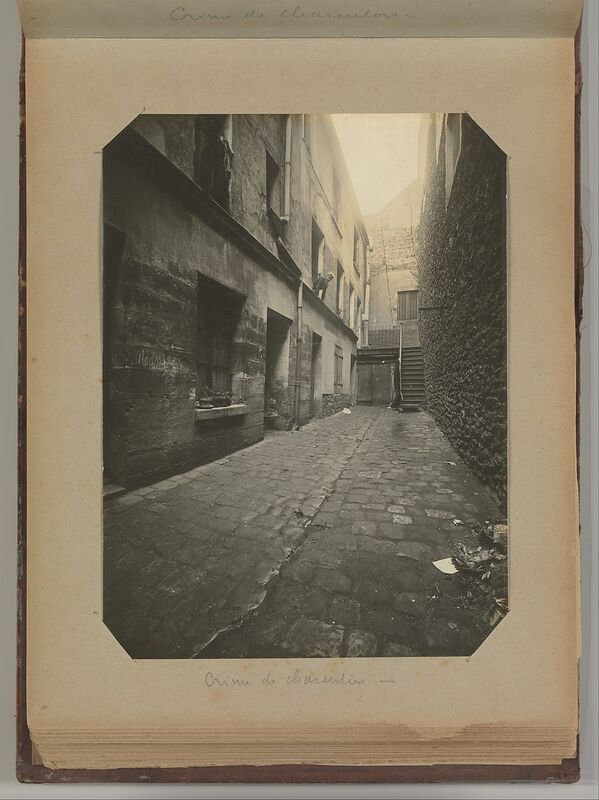

Take a look at some selected pages from an album of Paris Crime Scenes, attributed to Alphonse Bertillon:

Take a look at some selected pages from an album of Paris Crime Scenes, attributed to Alphonse Bertillon:

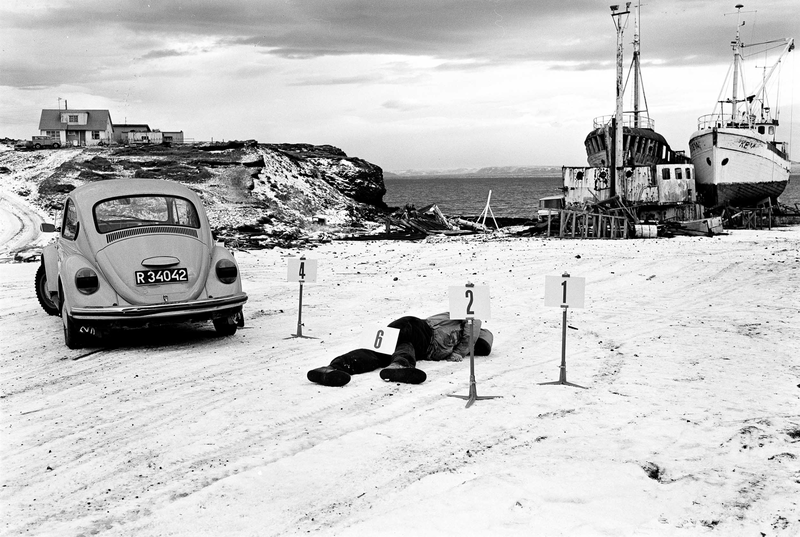

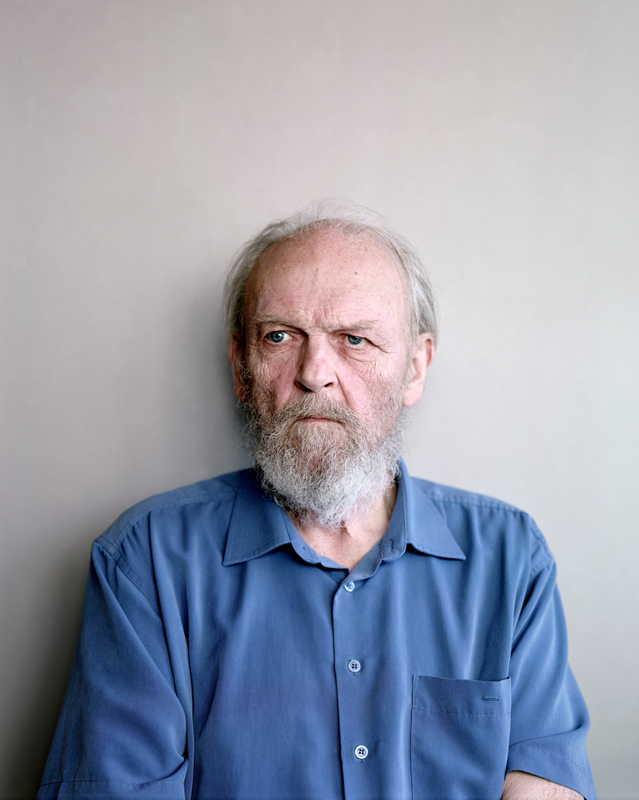

Here are some more photographs from Sugar Paper Theories for comparison:

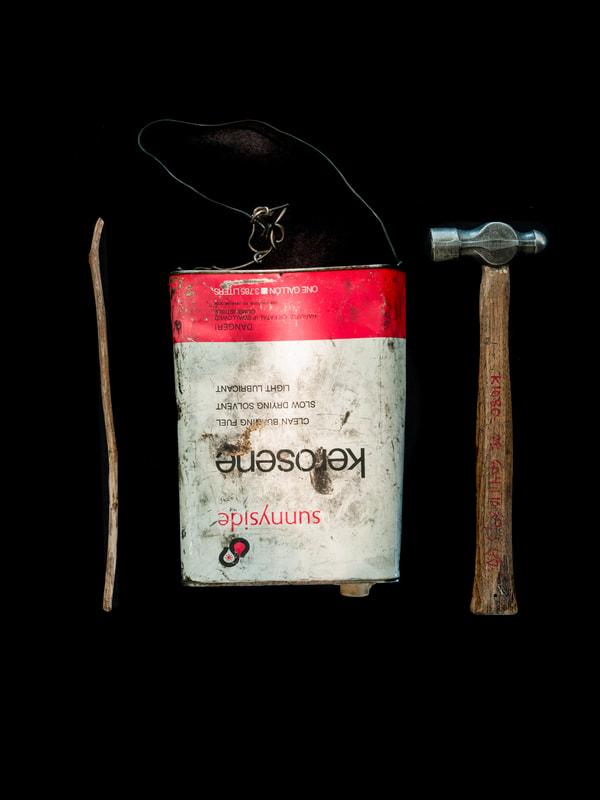

There are some striking similarities in these two sets of photographs. Police and forensic photography comprises different genres. In the examples here we can see location shots (of buildings and streetscapes where crimes may have been committed), still life arrangements in interiors (walls, objects etc.), portraits (head and shoulders and full length shots), photographs looking down at the floor, and photographs of corpses (or a recreation using a dummy). Of course, Jack Latham's pictures were taken long after the original crime and don't depict the criminals or victims. However, he conjures up the feeling of a police investigation by using the typology of crime photographs. The following interview with Diane Dufour, curator of the Burden of Proof exhibition at The Photographers' Gallery in 2016, explores some of the issues surrounding forensic photography:

Contemporary forensic photography can be broken down into different types as follows. The physical nature of evidence dictates the technique that is used:

Forensic photographs tend to be taken from three possible ranges:

Source: Things you need to know (but don't) about forensic photography

- Identification Photography: 'mug shot' pictures of suspects and criminals.

- Necropsy Photography: photographs taken before and after the victim's clothes are removed and while the autopsy is being carried out to document the state of the different tissues and organs.

- Panoramic Photography: long-range shots that establish the location of the crime scene with respect to the terrain.

- Photomacrography: close-range photographs of small objects.

- Photomicrography: a digital image of an object viewed under a magnifying glass or a microscope.

- Stereophotogrammetry: a technique used to reconstruct 3D scenarios based on their 2D images.

- Trace evidence photography: techniques such as ultraviolet and infrared photography to detect evidence that is present in trace amounts.

Forensic photographs tend to be taken from three possible ranges:

- Overview: images that document the exterior of the crime scene venue. They include pictures of the exits and entrances, pictures of each room (taken from overhead and each corner of the room), and those of the spectators at the scene. Pictures of the spectators can later help identify witnesses and suspects.

- Mid-range: images of objects in such a way as to establish their relation to the surroundings. They are used to determine distances between different objects at the crime scene.

- Close-up: close-range shots of small features such as scars, wounds, serial numbers, etc. Usually these images are taken in sets of two, one with a ruler for scale, and one without the ruler.

Source: Things you need to know (but don't) about forensic photography

Can you recognise any of these types of photographs in the images below, from Sugar Paper Theories?

Mystery, crime, ambiguity and the grey area between fact and fiction are themes that can be found in the work of other contemporary photographers. Consider the following examples:

Sugar Paper Theories revels in its inconsistencies and mistakes, and its overt embrace of blind alleys and dead ends gives the photobook its originality. It’s a smart example of an intentional, unsolvable muddle, giving form to the vexing uncertainty of human memory.

-- from a review by Loring Knoblauch

Activities

- Imagine you are a forensic photographer. Stage and document an imaginary crime scene. Think carefully about location and props. Consider the different types of images you could make - wide, medium and close-ups. Think about the time of day and lighting. Will you need to use flash? Will you photograph some of the evidence separately (as if you were in a forensic laboratory) or only on location? Don't forget to take two pictures - one with and one without a ruler. Present your photographs in an official looking dossier or display (like those you can see in TV crime dramas). Alternatively, choose a familiar location, a place perceived as safe and comfortable and then, without staging or intervention, photograph this forensically. Is it possible through your choice of framing and focus to imbue a sense of tension, caution, fear or suspicion?

- Research examples of police mug shots. Either collaborating with a partner, or using the timer on your camera, create a series of mugshot style self-portraits. Like Cindy Sherman, you may want to experiment with disguises and taking on different personas. What makes a mugshot such a distinctive type of portrait?

Wider reading

Visible Proofs, Forensic Views of the Body.

Can we trust a photograph?

Crime, Seen: A history of photographing atrocities.

Susan Sontag 'Regarding the Pain of Others'.

Can we trust a photograph?

Crime, Seen: A history of photographing atrocities.

Susan Sontag 'Regarding the Pain of Others'.

Related PhotoPedagogy resources:

|

The Photograph as Evidence. Since its 'invention' in the 1830s, photographs have been used as sources of evidence. The direct (indexical) relationship between the sun's rays and the resulting image makes photographs seem reliable as sources of information. But how reliable are photographs, really? |

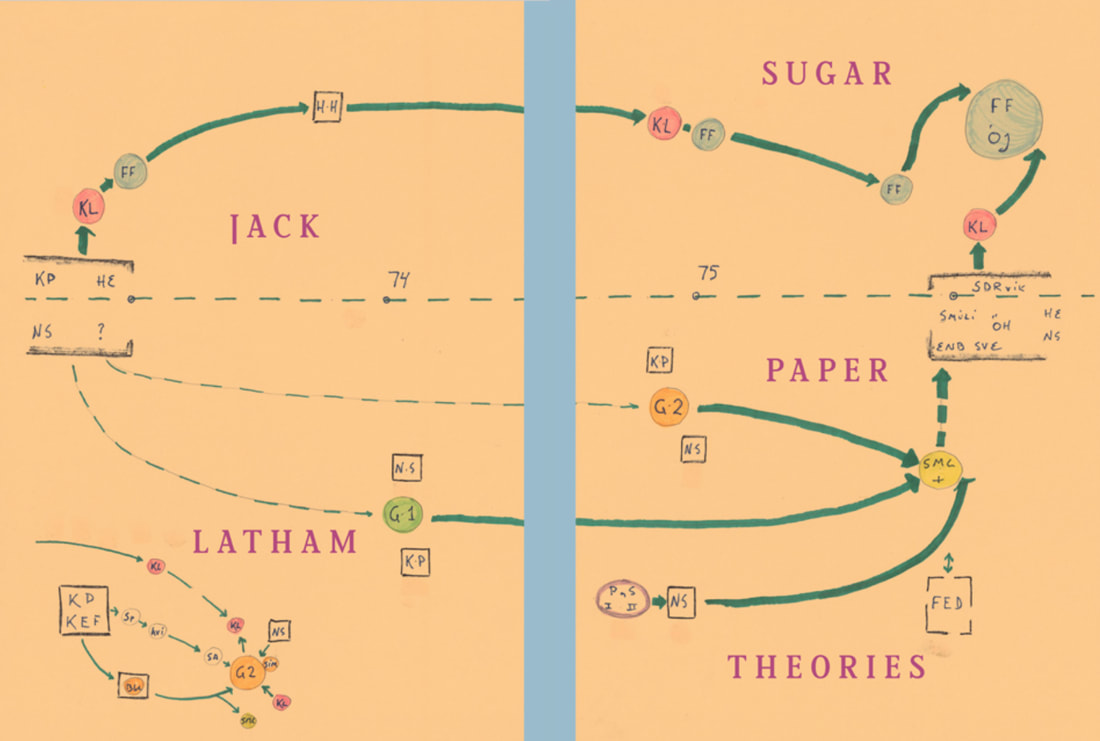

Part 3: Sugar Paper Experiments

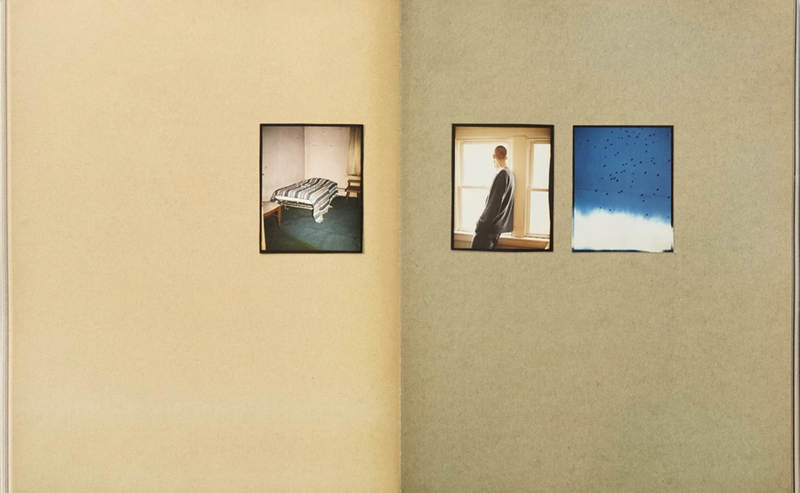

Photobooks - as opposed to prints, exhibitions or websites - provide a very particular way of presenting photographic images. The photobook, along with other printed documents such as newspapers and magazines, has played a vital role in the history of photography. Sugar Paper Theories exists as both an exhibition of prints and a limited edition (and very collectible) photobook. How can we take inspiration from the design of the photobook? How might we experiment with a similar variety of materials, images and texts, to create our own photobooks? Here's a reminder of what Jack Latham's book looks like:

For discussion

- Why have photobooks been such an important part of the history of the medium? What are their advantages and disadvantages compared with other forms of display and distribution?

- What is a conspiracy theorist? Why might Jack Latham have wanted Sugar paper Theories to look and feel like a dossier of information, collected by an obsessive conspiracy theorist (rather than a more conventional book of photographs)?

- What happens to a photograph when it is given a title, caption or is displayed near a piece of text?

Threshold Concept #7: Context is everythingPhotographs, are polyvalent - their meanings are hard to pin down and one photograph can mean many different things to different people. Threshold Concept #7 reminds us of this. All photographs are mysterious, even those that appear to present straightforward facts. Sugar Paper Theories exploits the ambiguity of photographs but also draws out their multiple meanings and inferences through various different printing techniques, the scale and sequencing of the images and the inclusion of various types of writing. This creates a rich web of information, a kind of puzzle for each individual reader (viewer) to untangle and interpret.

If you have ever tried to put a sequence of pictures into an order, you will have realised that moving even one picture changes the meaning of the whole. Imagine designing a book as sophisticated as Sugar Paper Theories. This is not something that could be done by one person. As is so often the case with complex photographic projects like this, a team of collaborators worked together on the project. The resulting book is the product of their collective work. |

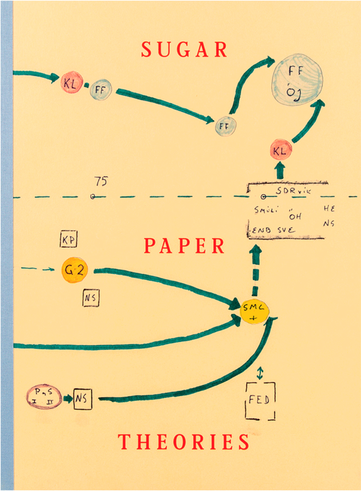

Sugar paper (what Americans refer to as construction paper) is associated with primary school art. It's relatively cheap, comes in an array of not particularly vivid colours, absorbs media easily and is the type of paper you might use for a quick sketch. The sugar paper in Latham's book may refer to the diagrams created by students of the murder case. Sugar paper features as a material in Gregory Halpern's 'Omaha Sketchbook'. Halpern originally pasted images cut from his contact sheets onto faded pieces of sugar paper as a way of sequencing the work. These were first reproduced in book form in 2009 by J&L books in a spiral bound edition of 30 on white photocopy paper. Mack have since created a larger edition which reproduces the look and feel of the sugar paper sheets.

In Sugar Paper Theories, Latham uses an interesting colour coding system to present different types of information and image in the book: reenactment photos taken from police archives (on black paper), related newspaper articles (on pink paper), diary entries from one of the suspects (on thin white paper), and detailed explanatory texts (on yellow paper). Why might he have done this?

Activities

|

Related PhotoPedagogy Resources:

|

What is a photobook? Why are they important and how do you make one? If you've ever wondered what a photobook is and you plan to have a go at making one, this is a good place to start with lots of inspiration and resources to get you started. |

If you have any queries regarding these resources, or if you would like to share any student work produced in response to these themes, you can contact PhotoPedagogy here.

Additional links

The Royal Photographic Society

Additional links

The Royal Photographic Society