|

In this short film we see the American photographer, Garry Winogrand, at work on the streets of Santa Monica, California in the early 1980s. Winogrand is famous for his no-nonsense approach and his modest claims for photography. In the film he talks about what he's trying to do, about the strategies he uses to avoid making conventional pictures. Most of all, we see him struggling with real life in all its ordinary strangeness. He breaks off frequently during the interview to make new photographs. He seems compelled to photograph everything, to see how it might look as a photograph. He once famously said:

There is nothing as mysterious as a fact clearly described. |

|

Unlike the other arts, that begin with a blank canvas or an empty stage, photography begins with the world. The job of the photographer, it might be argued, is to select rectangular or square sections of reality, in the form of reflected light, to stop and fix forever. Choosing where to put your body, what to include, what to exclude and when to click the shutter are very different processes to those used by artists in other fields.

Some initial questions:

- In what sense can a "fact clearly described" be "mysterious"?

- Do photographs document or create reality?

- What is the difference between a construction and a disclosure?

- How is photography similar to other forms of art? How is it different?

- How do photographs change our relationships to things?

Framing a view

|

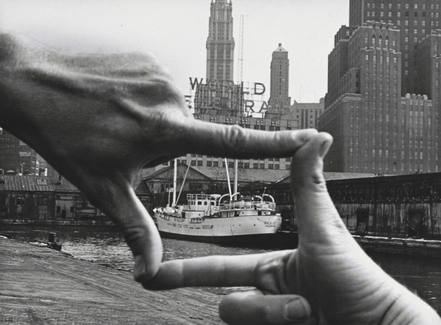

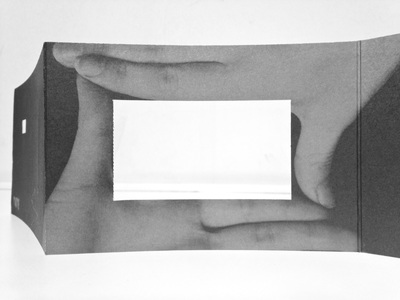

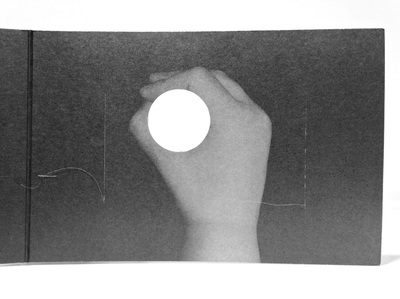

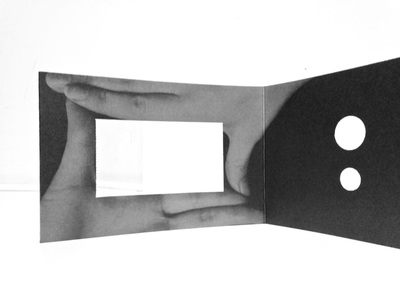

In 1971, artist and curator Willoughby Sharp invited 27 artists, including John Baldessari, to create ephemeral artworks on a derelict pier in New York harbour. The photographers Harry Shunk and Janos Kender documented the projects. On the pier, Baldessari used his hands to mimic the view of their camera, emphasising the framing choices made by the photographers.

Putting aside the issue of whose work of art this is, Baldessari's or Shunk and Kender's, the image neatly presents one of the key issues in photography - where to place the edges. This photograph presents a frame within a frame. Imagine if Baldessari had moved his hands a few centimetres in any direction. Is the intended picture of the boat inherently more interesting than the architecture, the water lapping against the pier, the sign? Photographers make choices. This; not that. Photographs are the results of those choices. |

Take a careful look at the photographs below. Think about where each photographer has decided to place the edges, what he or she has decided to include in and exclude from the frame. What choices has s/he made?

Photography is a system of visual editing. At bottom, it is a matter of surrounding with a frame a portion of one's cone of vision, while standing in the right place at the right time. Like chess, or writing, it is a matter of choosing from among given possibilities, but in the case of photography the number of possibilities is not finite but infinite.

-- - John Szarkowski

To crop or not to crop

Cropping is different to framing. Framing is what you do when you take the picture, working out what to include and what to exclude. Cropping happens later, either in the darkroom during enlarging and printing, or in digital editing software.

|

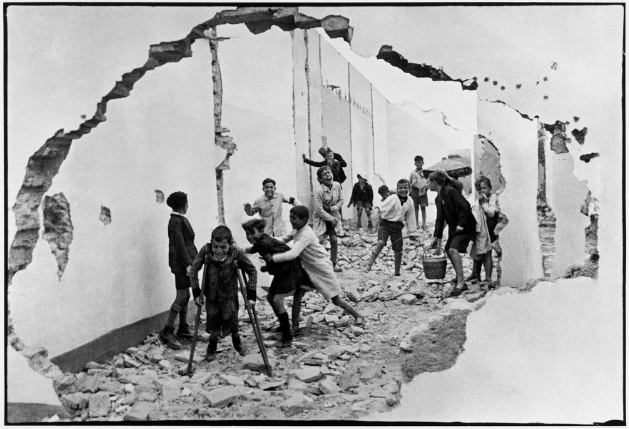

Henri Cartier-Bresson carefully framed his photographs but believed strongly that photographs should not be cropped in the darkroom.

Interviewer: You’ve been known for never cropping your photos. Do you want to say anything about that? This approach is often referred to as the Decisive Moment, after the English title of his famous book. His prints feature a black border (see above) to indicate the edge of the negative, proof that no cropping has taken place.

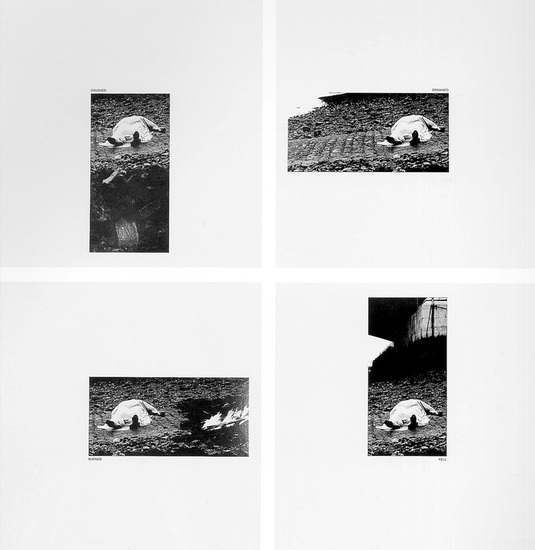

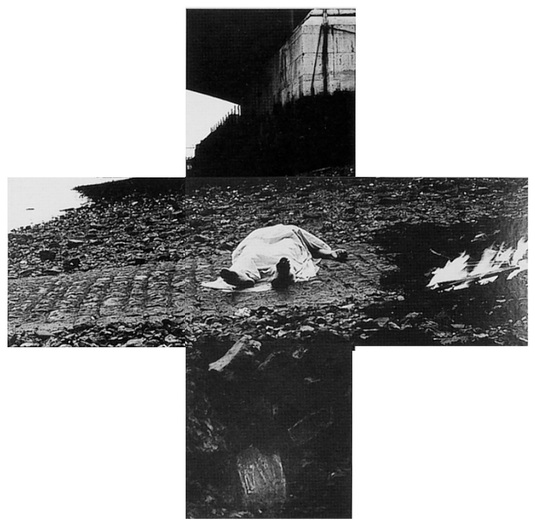

However, lots of other photographs are routinely cropped, especially those that appear in newspapers and magazines, often accompanied by words. Take a look at John Hilliard's 'Cause of Death' (above right). We are presented with four images featuring what looks like a dead body. The death appears to have four separate causes: Crushed, Drowned, Burned, Fell. However, we soon realise that the body is identical in all four pictures. The image below shows how Hilliard cropped a single photograph, in four ways, to tell four different stories. For much of its history, photography was seen as a kind of evidence, proof that something had happened (you could refer to TC2 and the notion of an index or trace). Hilliard is interested in the ways photographs can be used to provide unreliable evidence, to tell lies and deceive. They do this by only ever showing us part of the whole truth. |

Some suggested activities:Modern cameras often have either one electronic viewfinder (a screen at the back of the camera which doubles as an interface) or two viewfinders (electronic and optical). There is a difference between composing a shot with your eye pressed to an optical viewfinder and using an EVF. The purpose of the following activities is to foreground the process of looking, framing and composing a shot without the aid of camera.

|

- Give students a 6x4 inch piece of white card. Tell them they have only one 'shot' available. Ask them to consider what they would like to capture and (possibly with the aid of a viewfinder) commit the scene to memory through careful looking. Then, ask them to make a sketch of their chosen subject, trying to remember the specific arrangement of forms and shapes, the proportions of objects, dominant lines, the distribution of space within the composition etc.

- A further activity might compare framing a view with cropping afterwards. Students could be asked to crop a chosen image (in the darkroom or digitally) in several different ways, thus creating alternative compositions and, possibly, different stories (like the John Hilliard image above).

Remember, not everything is a picture. A good eye can edit before the shutter opens.

-- Craig Coverdale

Objective/Subjective framing

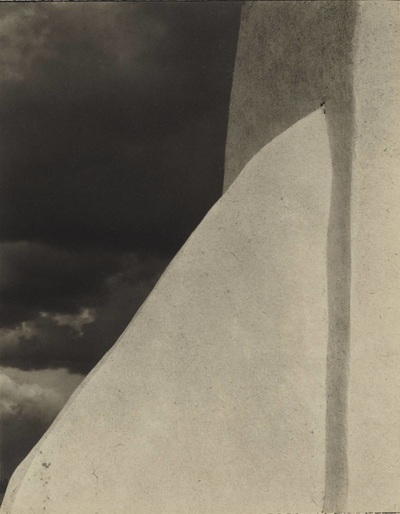

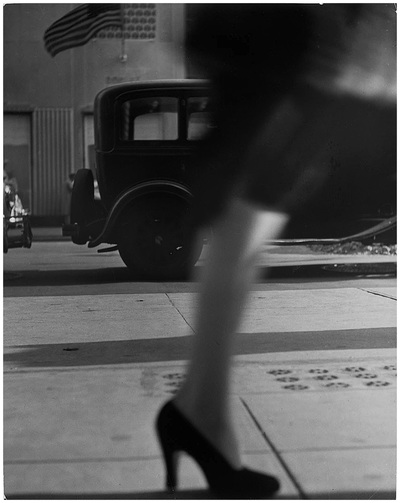

Consider these two photographs:

In photography you can never express yourself directly, only through optics, the physical and chemical processes. It is this sort of submission to the object and abnegation of yourself that is exactly what pleases me about photography. What is extraordinary is that, despite this submission and abnegation, the personality of the photographer shines through all the obstacles. In the end, images convey personality just as strongly as in a drawing.

-- Brassai

Brassai seems to suggest in this statement that all photographs contain elements of objectivity and subjectivity, that despite the inherent objectivity of the photographic tools and processes, the personality of the photographer is bound to reveal itself in the final image. This relationship is clearly affected by the choices a photographer makes about framing the subject.

In terms of the way these subjects (above) have been framed by the camera, where would you place them on a scale from subjective to objective? What about other photographs you know and admire? What about your own images? What helped you to decide where the photographs should be placed?

In terms of the way these subjects (above) have been framed by the camera, where would you place them on a scale from subjective to objective? What about other photographs you know and admire? What about your own images? What helped you to decide where the photographs should be placed?

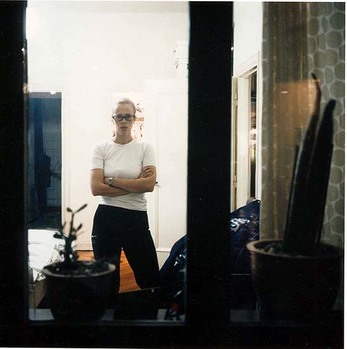

A room with a viewDear Stranger, I am an artist working on a photographic project which involves people I do not know…I would like to take a photograph of you standing in your front room from the street in the evening. A camera will be set outside the window on the street. If you do not mind being photographed, please stand in the room and look into the camera through the window for 10 minutes on __-__-__ (date and time)…I will take your picture and then leave…we will remain strangers to each other…If you do not want to get involved, please simply draw your curtains to show your refusal…I really hope to see you from the window. Windows provide us with a ready-made frame. A photograph of a window could be considered a frame within a frame. Several photographers have explored this visual pun.

|

|

|

Here's a slightly different way of looking at framing and windows in the context of film. Hitchcock was a master of composition and in 'Rear Window' his hero is a documentary photographer played by James Stewart. This short commentary of the opening minutes of the film makes the point that Hitchcock uses the motif of the window within a window to help tell the story. In feature films like this, projected at the cinema, we are seeing 24 individual photographic frames presented every second. This gives the illusion of continuous movement. The artist Douglas Gordon reveals the careful framing decisions made by Hitchcock in '24 hour Psycho', a version of the famous film dramatically slowed down to 2 frames per second so that every directorial decision is visible. |

Framing the family

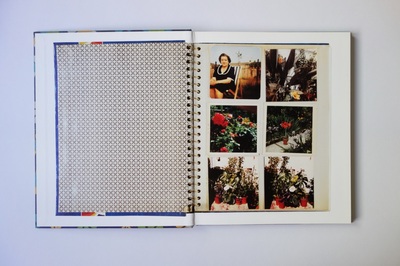

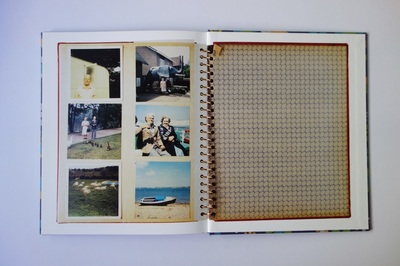

Julian Germain's wonderful photobook 'For Every Minute You Are Angry You Lose 60 Seconds of Happiness' has a cloth binding with a vaguely 1970s domestic floral pattern. The inside front and back covers provide a kind of framing device for the rest of the book. We are presented with photographs of photographs, specifically a dog-eared family album featuring a typical combination of portraits, landscapes and prize flowers. As Julian Germain explains:

‘I met Charles Albert Lucien Snelling on a Saturday in April, 1992. He lived in a typical two up two down terraced house amongst many other two up two down terraced houses… It was yellow and orange. In that respect it was totally different from every other house on the street…. ….Charlie was a simple, gentle, man. He loved flowers and the names of flowers. He loved colour and surrounded himself with colour. He loved his wife. Without ever trying or intending to, he showed me that the most important things in life cost nothing at all. He was my antidote to modern living.’

One of the ways we confer importance on photographs is to frame them in various ways. We put them in physical frames and give them pride of place on the chest of drawers or mantelpiece. We may even hang them on the wall. Or, we frame them in an album and occasionally take it off the shelf to flick through. Or at least we did before digital technology began to take over. Now, if we can be bothered, online companies offer to create a special photobook just for us (for about £20). Or Facebook generates an automated video for us to celebrate so many years of family and friendship, binding us still further to a virtual, dematerialised online album. More commonly our photographs languish, largely unseen, on the hard drives of our computers.

|

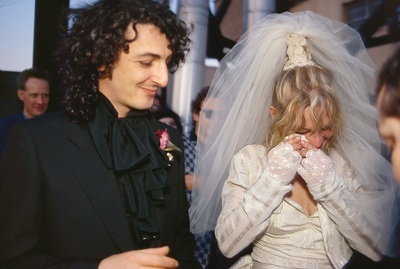

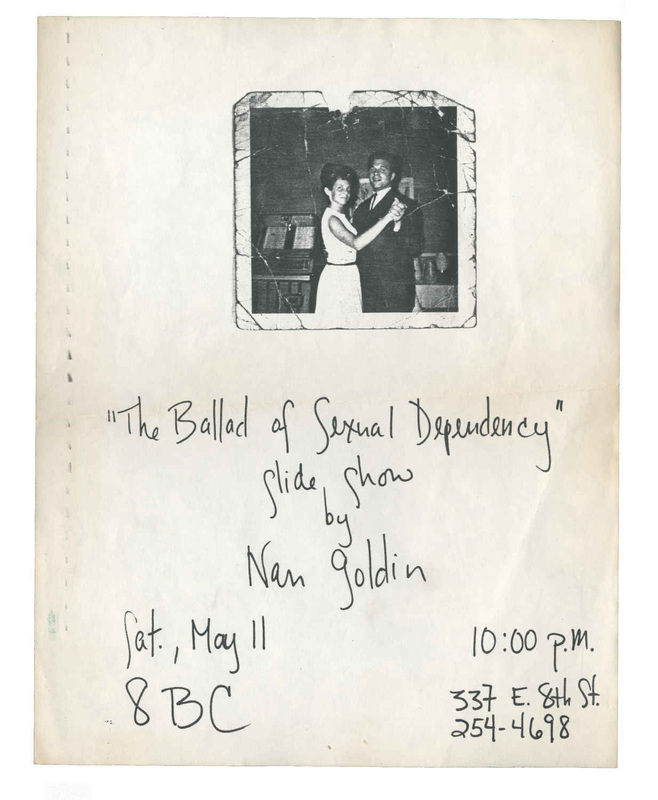

Nan Goldin's personal diary of photographs that make up 'The Ballad of Sexual Dependency' began life as a slideshow featuring approximately 300 constantly changing images projected on the wall to a rock soundtrack. A book version was first published in 1986. It is a celebration of youthful vitality, a chronicle of bohemian lifestyles and an alternative family album. It's also, like all family albums (and all photographs) a record of loss. Many of those featured in the slideshow and in the pages of the book lost their lives to drugs or HIV. By framing these people in the camera and subsequently through projected slides or in the pages of a book, Nan Goldin has immortalised them.

A lot of people seem to think that art or photography is about the way things look, or the surface of things. That's not what it's about for me. It's really about relationships and feelings [...] It's about emotional obsession and empathy. |

Some suggested activities:

If photography is an art of selection, rather than invention, one of the challenges faced by all photographers is the need to make choices about which image (of the many tens, hundreds or thousands taken) will be selected for special treatment (enlargement, printing, framing, publishing etc.)

- Create an alternative family album featuring your friends. Consider capturing the in between moments and seemingly insignificant objects rather than formal, posed portraits. How do you represent the quality of your relationships in a sequence of photographs. It could make a great photobook.

- Locate one of your own family's photo albums. Scan/photocopy some of the pages/images. Adapt them in some way, perhaps adding text or other mediums. You may be able to find someone else's family album in a junk or charity shop. What kinds of stories does it tell? How did it end up there? What can you do to interpret, re-stage or re-purpose it?

- Choose one of your own photographs. Try framing (presenting or displaying) it in at least three different ways. How does this change the way a viewer might interpret it?

After the taking

I don't think the essence of photography has the hand in it so much. The essence is done very quietly with a flash of the mind, and with a machine. I think too that photography is editing, editing after the taking. After knowing what to take, you have to do the editing.

-- Walker Evans

|

|

In this video, William Klein discusses his choices as a photographer. He shows us his contact sheets, the sequence of frames, and gives us an insight into why some images are successful "photographs", to use his terminology, and some aren't. In the days of film, the contact sheet (and slides arranged on a light table) was a way to see a set of images together and make comparative decisions. Some software programmes still allow you to create, print and analyse contact sheets and viewing images in this form is still part of the digital photographer's approach to editing. Annotations can be made, crop marks indicated, images rejected or selected. Reflect on your students' editing processes. What rationale do they use to make selections and decisions? Why this, and not that?

|

An art of production, not just reflection

|

Earlier we discussed the idea of a photograph being an index and/or a trace. Photographs are evidence of something having existed. But photographs are also pictures. In other words, photographs of particular things are produced by photographers for a reason. The frame, the edges around the image, create a picture of something. Take this photograph by Jeff Wall, for example (we've encountered his work in TC1). David Campany writes about it at length in this great article.

To summarise, the photograph appears to be a documentary image of an actual semi-industrial landscape on a dull day. Two paths cross in a field, one slightly crooked. Why has the photographer chosen this spot? Why has he chosen the title 'The Crooked Path' rather than 'A Crooked Path'? How are we meant to read this photograph? What is it that draws our attention - the paths, the grass, the bee hives, the trees and telegraph poles, the factory in the background, the light, all of these things? Campany wonders whether this a "cinematic" scene, prepared in advance, or is it a documentary photograph, a real place that, once discovered, has simply been "framed and photographed"? How real or artificial is the picture? On balance, it appears to be more documentary, more real, but how can we really know, especially with such an odd title?

|

The photograph contains certain facts - things in the world - and these traces are captured by the camera. However, the paths, the bee hives and the factory all suggest a human presence that is missing from the photograph itself. These are more iconic traces. Added to this is the title itself which suggests a possible symbolic interpretation:

There is nothing particularly special about this path. What might transform it is the way in which it has been photographed and how the photograph’s title might encourage us to make sense of it. So what might be ‘The Crooked Path’ here? Is it the path between nature and industry, perhaps? Between the country and the city? Between subsistence farming and corporate food production? Between nature’s chaos and modernity’s fantasy of order? Between civilisation and its discontents? Between summer and winter? It could be one, or all, or none of these [...] And the brute fact of the path is important too. A path is a trace, so a photo of such a path is a trace of a trace.

-- David Campany

Imagine Jeff Wall had placed his tripod closer to the bee hives, ignoring the paths altogether. Or what if he turned the camera slightly to the right where the path is less clear and we can no longer see the bee hives. The scene would not look substantially different. Imagine that he then titled the photograph 'Untitled, 1991'. How would our reading of the picture be different and why?

Photography is an art of selection rather than invention...Discuss

How true is this statement in relation to this photograph by Thomas Demand?

TC#4 on PinterestLinks referred to in this article and others besides are included in this TC#4 Pinterest board. We'll keep adding to these as we discover new resources.

Please use the comment boxes below to share any feedback or thoughts that you might have. |

By Jon Nicholls