"I See", said the blind man

|

'Memories, hopes and fears can all be multiplied by a photograph and contexts inevitably shift as time passes.'

I wrote that sentence a while ago in a different context, but I'm questioning it now. Something's changed, aside from placing it here. Perhaps I meant 'meanings': 'Meanings inevitably shift as time passes.' Still, I'm not sure. Meanings, Contexts; Contexts, Meanings. Photography is slippery and whilst these words certainly are different, in our dark (and light) art, boundaries often become blurred; contexts and meanings ebb and flow restlessly. Simply put, meaning is derived from context, whilst context is the information that surrounds something (which in most cases here refers to a photograph). We form our understanding of a photograph not just from what is in it, but what we know about it. Which might be related to the subject matter, but equally could be shaped by numerous other factors. But for the moment, back to those two words. Here's the dictionary definitions: context noun

meaning noun

Some of the initial thoughts here draw heavily on The Ongoing Moment by Geoff Dyer. As photo-related brain exercise goes, it's a multi-gym read. Playful repetitions (of ideas, across images and time) abound. Dyer identifies re-occuring themes within the medium, adding context to and across works, demonstrating throughout how an agile mind can draw new meanings. For Dyer, every image produced by a photographer becomes part of an extended conversation, not just with the past and comparable images that have come before, but also with the future. Photographs are ongoing moments, recycling subject matter, whispering back and forth of the nature of photography and of humankind itself. |

New ways of looking

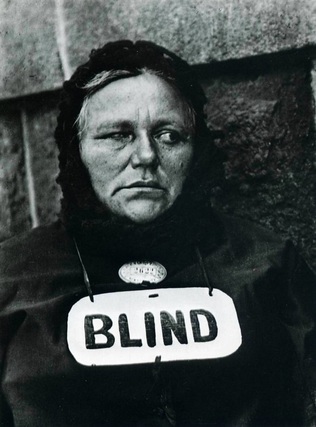

Paul Strand's 'Blind Woman' is often considered an iconic photograph. Certainly for a young Walker Evans - on discovering it in a journal in 1928 - it proved a catalyst for a lifetime dedicated to image taking. But perhaps a current student, at least on first glance, might be less stirred. Or at least stirred in a different way: Images of the poor are now all too familiar, but such 'branding' of the poverty-stricken is less of our time. In this regard the image delivers a blunt unfamiliarity - the caption 'BLIND' exists within the frame (rather than simply below it) serving as an additional weight on the subject's shoulders. Yet gather wider still and, as is so often the case with photography, much more is going on than meets the eye. Blind indeed.

Look at the things around you, the immediate world around you. If you are alive, it will mean something to you, and if you care enough about photography, and if you know how to use it, you will want to photograph that meaningness. Suggested activity:

*When it comes to context and potential meanings, Strand's image offers more layers than a multi-storey car park in a Photoshop PSD file. I'll resist the urge to peel these away here - students need to work a bit to learn - but this link here, or perhaps this, might prove useful starting points. Gathering context - research, if you like - should be an activity students grow to love. |

Running themes, pass it on

Regarding The Ongoing Moment, a running theme (although a relay race might be more appropriate) is how key figures such as Alfred Stieglitz, Paul Strand, Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and Diane Arbus have often photographed the same scenes and objects. As with a sprinter's baton, Dyer proposes that certain themes - be it park benches, hats, picket fences or blind beggars - have been handed over and subsequently run with throughout the history of photography, each photographer extending on the observations of the last. Dyer constructs a narrative in which image makers - many of whom never met in their lives - constantly come into contact with one another. Arguably, the facts become secondary. Dyer draws interesting parallels - tracks for our imaginations to run down (I'm stuck in an athletic analogy) - that offer refreshing contexts and new meanings as photography, time, technology - life - all dash by.

Beyond the blindingly obvious, these images share other common features (a useful exercise for a class might be to try to identify these), for example: all the images above appear to be candid street photographs (not so, at least one is staged); New York is a reoccurring location; within four of the images a blind person appears to be playing music (but just as they don't see the photographer plying his trade, we don't hear theirs - an unagreed [non]trade). Importantly, Dyer adds further context - and subsequently, meaning - by highlighting additional concerns of photography at these various times. For example, consider the following:

- Is it acceptable to take photographs of people when they are unaware that you are doing so?

- How can you capture a person at their most genuine (i.e. when they are unaware of - blind to - a photographer's presence)?

- What are the moral and social responsibilities of a photographer when it comes to documenting the vulnerable...daily life, truth...anything?

Plenty of context for thought from which new meanings can be drawn. These questions remain ongoing dilemmas in the 21st Century. Photography's preoccupation has always been about our ways of seeing; it is of little wonder the blind can hold such fascination as subject matter.

Sophie Calle, Voir la mer (2011) on display in Japan

|

French photographer and artist Sophie Calle has continued to explore blindness, a reoccuring theme in her work. Her film installation, Voir la mer (See the sea), shows: "a series of digital films related to Calle’s 1986 project The Blind, in which she asked blind people to describe beauty. One of them answered, The most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen is the sea, an endless sea. For Voir la mer, Calle found people living in Istanbul — a city surrounded by water — who had never seen the sea. She took them there and filmed the results." (source: NGCMagazine). For Sophie Calle's The Last Image (2010), each piece has three components: a photograph of a person who went blind, their description of the last thing they remember before they lost their sight, and Calle’s photographic re-creation of the memory.

In Blind with Minibus, (left) Calle’s blurry photograph of a red bus re-creates the moment when a patient left her doctor’s office after a glaucoma treatment, her sight beginning to slip into blindness. |

Suggested activity:

- Consider the 3 components of Calle's 'Blind with Minibus', above, in isolation. For example, show only the image of the blurred minibus. Without context, this intentionally blurred image might easily be considered 'wrong'. However, paired with the accompanying portrait, our minds begin to close the gaps. We begin to 'see' something new, even when the images remain the same.

- A photograph's physical proximity to another and how this influences our perception of it e.g. side by side in a book, on a gallery wall etc.

- Whether we see the 'original' work as the artist/photographer intended - framed on a wall, in a specific location, via print, on screen, via digital projector etc. Often our second-hand viewings result in changes in scale, colour, texture and so on. That said some works are intended for mass re-production and embrace the omnipresent possibilities photography and digital media offer.

- The information that surrounds, precedes, accompanies or follows the encounter. A simple (but highly influential) example here is if the photograph has a title or caption (we'll come back to this). But other diverse influences might seep in - the surrounding noise; your emotional state; recent reading; what you had for lunch...

The following lessons, in various ways, provide possible avenues to explore:

Never noticed, honest

|

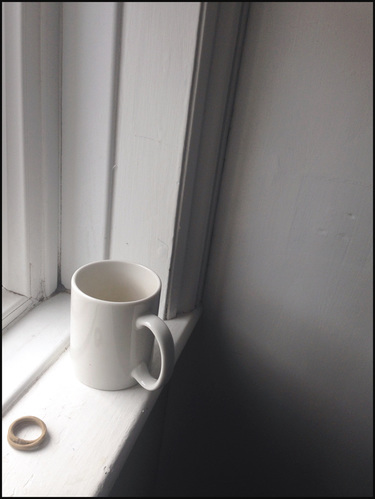

The meanings of photographs are never contained solely within the images themselves. This can be easily demonstrated by a quick glance at the most recent photo you have taken and deliberately kept (excuse a presumption that this is likely to be digital, and chances are on a mobile device too - but please, not an ephemeral SnapChat; the kept is significant) - choose the most recent 'survivor'. What though is the reason - context - for holding its pixels intact? Your justifications no doubt extend beyond subject matter alone.

However practical, sentimental or plain absurd, we like to share these meanings. Try it with a group of students: ask them to show their most recent photo and watch them become animated as they elaborate on its existence, providing context, recalling recent memory. As means of demonstration, the image on the left is still warm from my iPhone. It is something and nothing: a mug and a hairband on a window sill. The light is pleasing enough, as is the limited colour - you might expect a photography teacher to have such sensitivities - but beyond that, it's a potential minefield, really. Although without context, you have no idea. |

I've just begun to photograph these 'Sill-Lifes', as I find them; abandoned at the top of our stairs. For reasons unknown, this daily detrius can trouble my wife. (Otherwise quite lovely, just don't rustle crisps). But like I said, something and nothing. Doesn't get there on its own you know.

Whatever my (or your) intentions, context doesn't necessarily gag an image from whispering alternative meanings. Connections are free to be made and conclusions drawn regardless, and the deeper your awareness of various contexts - be it colour relationships, genres, the illusions of surface, photographic typologies, whatever - the more possibilities can emerge (at least when viewing, knowledge can inhibit creativity too). Not everyone sees in the same way and, try as we might, some things refuse to be neatly tidied.

Whatever my (or your) intentions, context doesn't necessarily gag an image from whispering alternative meanings. Connections are free to be made and conclusions drawn regardless, and the deeper your awareness of various contexts - be it colour relationships, genres, the illusions of surface, photographic typologies, whatever - the more possibilities can emerge (at least when viewing, knowledge can inhibit creativity too). Not everyone sees in the same way and, try as we might, some things refuse to be neatly tidied.

Suggested activities:

- Challenge your students to produce a photograph that has a significant gap between what is seen within the frame (the subject matter) and the context that lies beyond it (the explanation that reveals its true value).

- How might interpretations of their image be altered by providing further context such as:

- a title

- a quote or song lyric

- a short story

- a formal explanation

- Revealing that it is part of a set or sequence

Signs that (don't always) say what you want them to say...

Two people died in that photograph: the recipient of the bullet and General Nguyen Ngoc Loan. The general killed the Viet Cong; I killed the general with my camera. Still photographs are the most powerful weapons in the world. People believe them; but photographs do lie, even without manipulation. They are only half-truths. … What the photograph didn’t say was, ‘What would you do if you were the general at that time and place on that hot day, and you caught the so-called bad guy after he blew away one, two or three American people?’ |

Eddie Adams' photograph, above, is one of the most disturbing, iconic images to emerge during the Vietnam War and receive global press coverage. It quickly became a symbol of the war’s brutality. Long after he had pressed the shutter Eddie Adams lived with a sense of blood on his hands - but not that of the victim, but rather the gunman himself. Adams felt he 'killed' the gunman by creating an image in which he was forever cast as a villain. The man being shot (Nguyen Van Lem) was the captain of a Vietcong “revenge squad” responsible for executing dozens of unarmed civilians that day. The gunman, General Nguyen Ngoc Loan was, within the context of war - and (rightly or wrongly) The Geneva Convention - a man at work. There were no winners here.

Suggested activities:

- Research the work of Eddie Adams and the context surrounding this photograph. *WARNING* This task might not be suitable for all students, the image was taken alongside a disturbing filmed sequence widely available online.

- Ask the students to devise a new title / caption for the work considering various perspectives. For example, a title written by:

Eddie Adams, the photographer

General Nguyen Ngoc Loan, the gunman

The family of Nguyen Van Lem, the victim - How might these captions change over time? For example, what title might the General have given the image moments after it had been taken? How might this have changed if devised in his final years, the remainder of his life spent under the shadow of the image?

Eyes wide shut...All photographs are ambiguous. All photographs have been taken out of a continuity. If the event is a public event, this continuity is history; if it is personal, the continuity, which has been broken, is a life story [...] Discontinuity always produces ambiguity. Yet often this ambiguity is not obvious, for as soon as photographs are used with words, they produce an effect of certainty, even of dogmatic assertion. |

|

|

When it comes to conflict - not just within the frame, but in matters of context, meaning and truth - perhaps Robert Capa's 'Falling Soldier' is the most debated of all images. The original title, above, has certainly proven to be misleading, at the very least regarding location.

Taken during the Spanish Civil War, the photograph appears to capture a Republican soldier at the moment of death, collapsing backward after being fatally shot in the head. The image was quickly acclaimed as one of the greatest war photographs ever taken, however allegations later emerged that the photograph was faked or staged. Perhaps most damningly for Capa it was suggested that the soldier was actually shot whilst acting out a moment of battle for the benefit of the photographer. These significant doubts have been supported with evidence suggesting the location was not as originally told, alongside the discovery of staged photographs taken at the same time and place. |

|

In the video above, artist Cornelia Parker discusses 'The Falling Soldier'. She shares a range of contexts, from historical insights to childhood memories that have shaped her fascination with the photograph. Parker emphasises the qualities of photography - rather than, say, moving film - for preserving this "violence, in a quiet place" - a soldier in limbo between life and death, falling but never going to land.

|

The more I know about it [The Falling Soldier], the more fascinated I become, you can't pin it down. |

Suggested activities:

Why has photography proven such a powerful tool - weapon even - within times of conflict? What are the implications of creating powerful, disturbing or staged images? How important are accompanying titles, captions and / or headlines to provide context and truth, to sustain morale, or to pursuade or protect?

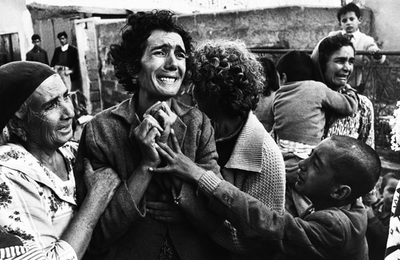

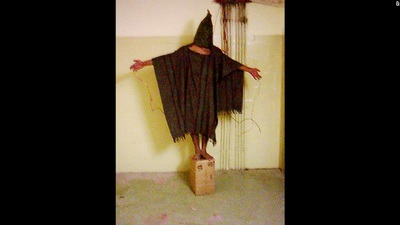

- Using the images below as starting points, challenge a class to add context, initially via any existing knowledge and then through wider research.

- Devise alternative captions for the photographs based on various perspectives of the situation. Follow the links on the image for further information.

Sorry if my captioning is not up to standard, but with all that sniper fire around, I didn’t dare wave a white notebook.

-- Larry Burrows to his editors

Further reading:

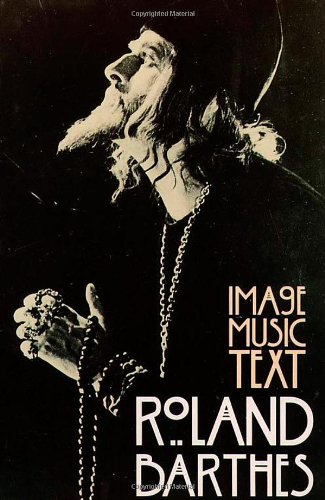

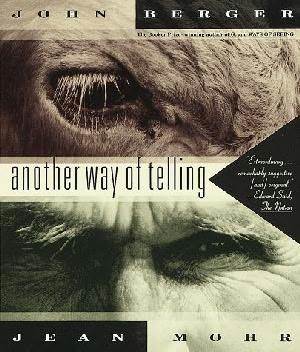

The following texts offer further insights into some of the ideas that might have been scratched at the surface here:

TC#7 on Pinterest

Links referred to in this article and others besides are included in this TC#7 Pinterest board. We'll keep adding to these as we discover new resources.

Please use the comment boxes below to share any feedback or thoughts that you might have. |

By Chris Francis