Each Threshold Concept has a supporting image inspired by our Photopedagogy camera. TC #6 shows a die, or a dividing line separating the result of a coin flip, indicating the contingent nature of photography.

Threshold Concept #6Photographs rely on chance, more or less. Chance is very important in photography. You can fight chance, tolerate it or embrace it. To some extent, all photographs are the result of chance processes.

As teachers of photography we want our students to gain control (the current buzzword is "mastery") over their materials and processes. We aim to help them develop critical understanding through focused research, refined outcomes that are personal and meaningful and the ability to experiment with a range of materials, processes and techniques. Debate still rages about whether photography is a craft or an art. Of course, it's a bit of both (and other things besides). However, how much control can a photographer reasonably claim over his or her materials? To what extent are all photographs the product of chance and how do we teach our students to deal with the contingent nature of the medium? NB: The ideas and examples in this TC are heavily indebted to Robin Kelsey's magnificent book Photography and the Art of Chance. |

Definitions

The relationship between chance and photography is contentious. A quick look at a dictionary definition suggests why:

Chance

nounadjective: fortuitous; accidental.

- 1. a possibility of something happening.

synonyms: possibility, prospect, probability, odds- 2. the occurrence of events in the absence of any obvious intention or cause.

synonyms: accident, coincidence, serendipity, fate, a twist of fate, destiny, fortune, freak, hazard

verb: do something by accident or without intending to.

Chance implies a loss of control, a reliance on luck or accident, rather than the agency of the craftsperson in charge of his or her materials. Chance has largely negative connotations. How then should we explore the role of chance in photography and how might we consider chance a friend rather than an enemy of the creative process?

Chance-sent thingsA photographer must be prepared to catch and hold on to those elements which give distinction to the subject or lend it atmosphere. They are often momentary, chance-sent things: a gleam of light on water, a trail of smoke from a passing train, a cat crossing a threshold, the shadows cast by a setting sun. Sometimes they are a matter of luck; the photographer could not expect or hope for them. Sometimes they are a matter of patience, waiting for an effect to be repeated that he has seen and lost or for one that he anticipates. Leaving out of question the deliberately posed or arranged photograph, it is usually some incidental detail that heightens the effect of a picture – stressing a pattern, deepening the sense of atmosphere. But the photographer must be able to recognise instantly such effects. |

Bill Brandt's choice of words here is interesting: "catch", "hold on", "momentary", "luck", "hope", "Incidental", "instantly". Putting aside for a moment those artists who deliberately embrace accidents and indeterminacy as part of their practice (we'll return to them later), in what sense do all photographs invariably contend with chance?:

- In most cases photographs represent a fraction of a second of lived experience and often result from the photographer responding instinctively to the world of things.

- Cameras 'see' the world differently to human eyes (something we encountered with TC#5). Unlike human eyes, the camera is monocular and omniscient. What the photographer sees the camera interprets.

- A photograph is (usually) produced by a machine operated by a person. Both are fallible.

- A photograph of a thing is not the thing itself. It is a new and different thing.

- Making a photographic exposure is really only one aspect the process of making a photograph. In the entire process of conception through to the printing and/or displaying of the image, chance plays a more or less significant part.

All the canonical works of photography retain some trace of the medium’s underlying, life-giving, accident-proneness.

-- Janet Malcolm

Surprise, surprise

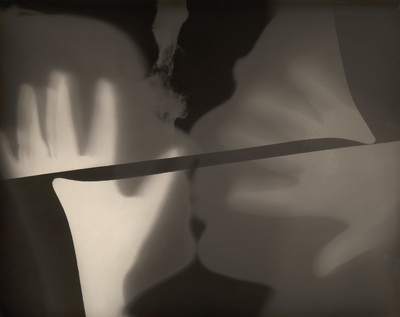

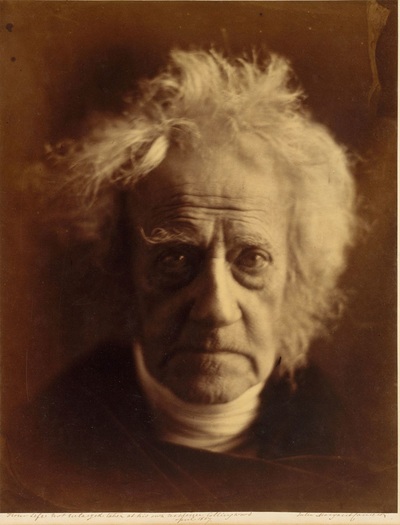

Each of the photographs below is a confrontation with the laws of chance. Man Ray's 'Rayograph' is the result of what looks like three separate exposures of objects placed on light sensitive paper in the darkroom: a pair of hands, kissing heads and chemical trays. Despite a great deal of skill and experience, the artist would not have been able to know precisely how the image would turn out until he developed it. Julia Margaret Cameron was criticised for the almost casual, out-of-focus appearance of her images:

In these pictures all that is good about photography has been neglected, and the shortcomings of the art are prominently exhibited [...] We are sorry to have to speak thus severely on the works of a lady, but we feel compelled to do so in the interest of the art.

-- The Photographic Journal, 1864

What we now consider to be a strength, her ability to capture the vivacity of her subjects, was considered a technical deficiency at the time. The use of long exposures and experimental printing techniques in the early years of photography also meant that photographers needed to be comfortable with a relatively high level of chance in the making of their images. The outcome could not be completely controlled.

Jim Rosenthal's iconic image of the American flag being raised on a Pacific island during WW2 is beautifully composed. So beautiful in fact that for many years the photographer repeatedly denied that it had been posed. It might surprise you, therefore, to learn that it was largely the product of chance. You can read the full story here. A different flag had already been raised and photographed that day. Rosenthal was late to the scene. When he realised that a second flag was being hoisted into position he instinctively took just one shot. He had no idea until he saw the picture printed that he had managed to capture the scene so well and, still less, that this one image would come to symbolise the heroism of the Allied forces in WW2.

Photography is prone to chance. Every taker of snapshots knows that. The first look at a hastily taken picture is an act of discovery [...] The conspicuous role of chance in photography sets it apart from arts such as painting or literature. Whereas in a traditionally deliberate art form, such as the novel, chance comes across as something contrived, in photography it comes across as something encountered. What does it mean that photography so often entails a process of haphazard making and careful sorting?

-- Robin Kelsey, Photography and the Art of Chance

Automatic for the peopleIt may seem that the technical advances made throughout the history of photography have all been attempts to limit the role of chance. The elaborate, risk-laden, inexact process of making a photograph in the 1850s, for example, would have felt very different from using today's autofocus, enhanced scene detection, WiFi enabled DSLR.

Is the fashion for Lomography and analogue film cameras amongst younger photographers in part a reaction against the automated, risk-averse world of the digital revolution? Are risk and chance essential components of art and therefore somehow more authentic? Does automation of the camera's functions free us to focus on composition and framing or does ease of use limit our creative control, tending to produce photographs that all look alike? |

|

Some questions:

- What is your attitude to the role of chance in photography? How much control do you attempt to exert over your equipment, processes and techniques?

- Do you have experience of creating a 'lucky' photograph? If so, when did you become aware of the picture's success? Did your realisation that the picture contained an element of luck (over which you had little control) change your view about its value?

- In what ways is it possible to make your own luck in photography?

Chance, Time and Speed

It comes down to risk, again and again. If you risk coming out, if you risk making pictures that aren’t good, you might discover something in a photograph that is the key. The very doorway to your own interest.

-- Joel Meyerowitz

Certain types of photography, it seems, require a greater tolerance of chance than others. Take street photography for example. Joel Meyerowitz is very articulate about the kind of behaviour required for successful street photography.

What can we tell from these 3 photographs below about the photographer's attitude to chance?

What can we tell from these 3 photographs below about the photographer's attitude to chance?

|

Seeing double.

|

A life of its own.

|

Disembodied.

|

|

Street photographers are comfortable with complexity. They typify the type of photographer who embraces chance wholeheartedly. However, they develop a range of strategies for coping with and making sense of the seemingly chaotic. A list of attributes required for street photographer might include:

|

You have to be ready for luck. ...a mysterious intersection of chance and attention that goes well beyond the existential surrealism of the "decisive moment". |

Dedication, experience, fearlessness and curiosity can all help the photographer capture great images on the street but those who embrace chance, rather than fight it, tend to make their own luck. Here's another great street photographer and one of Meyerowitz's heroes, Robert Frank, talking about one of the iconic photographs from The Americans and the "accidents that happen" that make it one of his "best pictures".

Serendipity

Great street photographs are often a product of serendipity. The word was first coined by Horace Walpole in 1833 to describe the process of discovering things by accident when not searching for them. In other words, it's our ability to observe rationally something that occurs by chance. Matt Stuart's photographs might be considered to be examples of serendipity - the chance collision of two or more different visual phenomena, made meaningful by the photographer's conscious choices about framing, camera angle etc. Stuart, like many other street photographers, takes advantage of a photograph's ability to flatten three dimensional space, bringing into relationship objects that exist separately in the real world. This is a concept related to the 'grammar' of photography (TC#8).

Shooting from the hip

Shooting from the hip introduces a further element of chance into street photography. This blog post by Eric Kim explains the optimum camera settings and technique that may lead to more successful images. However, part of the reason for shooting this way is capture more candid shots that challenge some of the conventions about what makes a photograph successful.

Suggested activity:

- Ask students to make a series of photographs of a busy place (lesson changeover in school, the classroom, the playground, a busy street) experimenting with composing the picture in a viewfinder and shooting from the hip.

- Record the experience of both types of shooting. What decisions were you able to make? What did you leave to chance? What equipment did you use? How did that affect the process of making the pictures? What skills/attributes did you need? What did you notice? How did it feel?

- Now, ask the students to review their two sets of images. Which approach yielded the best pictures and why?

A cast of the dice

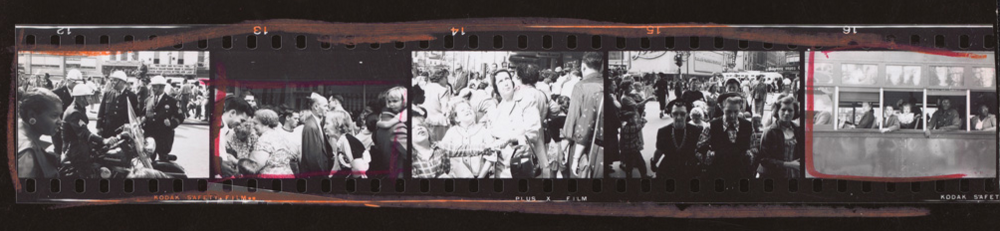

The way we read photographs is also prone to chance. No two viewers will see a photograph in the same way, regardless of the photographer's intentions. Roland Barthes famously refers to a particular detail in a photograph that strikes the individual viewer as significant as a "punctum":

A Latin word exists to designate this wound, this prick, this mark made by a pointed instrument: the word suits me all the better in that it also refers to the notion of punctuation, and because the photographs I am speaking of are in effect punctuated, sometimes even speckled with these sensitive points; precisely, these marks, these wounds are so many points. This second element which will disturb the studium I shall therefore call punctum; for punctum is also: sting, speck, cut, little hole - and also a cast of the dice. A photograph's punctum is that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me)

-- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida

Barthes calls the general cultural effect of the picture - genre, composition, subject etc. - the studium. The punctum, by contrast, is often a small detail, perhaps even of marginal significance to the overall impact of the photograph, which causes him to engage emotionally. Of course, this is also a very personal reaction and different for each viewer. Take this image for instance:

What is the studium of this photograph? We see a street scene in which children pose for the camera. The photographer has crouched down so that the assassin's head is cut off. The children are smiling, enjoying the attention of the photographer. Behind them, two young women, one half conscious of the photographer, are walking towards us down a busy street. The clothes tell us that it might be the 1950s, perhaps in urban, multicultural America.

Now, what might be the punctum for you? There are so many potentially poignant details in this picture - the dirty faces, the floral pattern on the gun holder's dress (almost hidden beneath a checked shirt), the horse motif on the boy's shirt, the awkward gesture of the two hands meeting, the boy's squinting eyes, the contrast between the fashionable pedestrians in the background with the grubby urchins in the foreground etc. For Barthes, the punctum was the boy's "bad teeth". (In another example, a portrait of the poet Tristan Tzara by André Kertész, Barthes is struck the writer's large hands and dirty fingernails.)

Here's what the photographer remembers about taking the picture above:

I had the nerve to stop this little family and say, Hold it. Flattered, they got into position. The mother took the boy's pistol and held it to his temple. he rolled his eye towards her, put his hand in hers and laughed happily. His big sister bent down to be in the shot, his little sister giggled. One picture. Two teenaged girls come rushing towards us, 1955 fashion-plates, men's shirts over their jeans rolled up above their ankles, white socks, curlers and scarves. Another picture.

I was thinking: these kids who hang around with dirty shirts and a mother who thinks it's funny to stick a gun in their faces are kids I might have crossed the street to avoid when I was their age. I thought: do a chapter, Gun, in my book. I thought: that fake violence, that real tenderness, those bad teeth (yes, that too). I thought: those poor kids.

-- William Klein

Suggested activity:

- Print a variety of photographs. Briefly explain the concepts of studium and punctum. Ask students to annotate the images using these terms, with particular emphasis on the punctum.

- Discuss their choices. How similar/different are they? What have they found poignant? How useful are Barthes' terms when exploring the meaning of photographs? Why does he compare the effect of the punctum with a "cast of the dice"? In what ways does the punctum "disturb" the studium? How objective/subjective can we be when analysing photographs?

- Now, ask students to choose one or two examples of their own photographs to share with other members of the class. Repeat the exercise, comparing the photographer's memories of making the picture with a viewer's analysis of studium and punctum.

Happy Accidents

If we accept that the photographer (however skilful and experienced) will always be contending with a certain amount of chance, one of the key skills we can attempt to teach students is the ability to recognise a 'happy accident'. Occasionally, when something goes 'wrong', a new and different kind of picture is made. This might challenge the photographer as well as a viewer because it doesn't conform either to the photographer's intentions or the viewer's expectations. However, this picture represents new knowledge about how the world can be 'seen' by a camera or other imaging device and should not therefore be dismissed as a mistake, at least until it has been carefully considered. Some artists/photographers are interested in deliberately breaking the 'rules' as a strategy (see below). But genuine errors can also be instructive and, sometimes, revelatory.

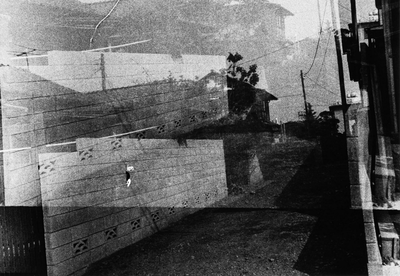

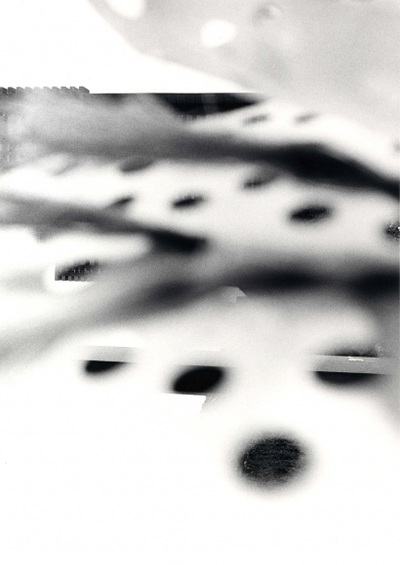

Consider, for example, Daido Moriyama's famous photobook 'Farewell Photography'. Moriyama had been a member of the infamous Provoke group of photographers who had already set out to challenge some of the conventions of photography with their are, bure, boke (grainy, blurry, out-of-focus) approach to image making. In an attempt to say goodbye once and for all to photography Moriyama sent a set of prints (damaged, mis-printed, scratched and rejected) to a publisher, giving him total control over the final look of the photobook. Subsequently, the majority of the negatives were burned. Or at least that's what Moriyama thought had happened to them until several others re-appeared recently, saved from the fire by the book publisher.

Consider, for example, Daido Moriyama's famous photobook 'Farewell Photography'. Moriyama had been a member of the infamous Provoke group of photographers who had already set out to challenge some of the conventions of photography with their are, bure, boke (grainy, blurry, out-of-focus) approach to image making. In an attempt to say goodbye once and for all to photography Moriyama sent a set of prints (damaged, mis-printed, scratched and rejected) to a publisher, giving him total control over the final look of the photobook. Subsequently, the majority of the negatives were burned. Or at least that's what Moriyama thought had happened to them until several others re-appeared recently, saved from the fire by the book publisher.

Perhaps the authority of the failed negative, with all its inherent possibility, could be restored. I imagined I could construct a book — a book of pure sensations without meaning — by shuffling into a harmonious whole a series of childish images.

-- Daido Moriyama

|

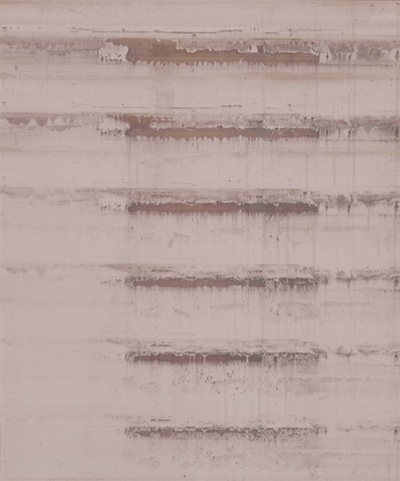

This series of pages from a student's sketchbook* explores what can happen when a 'mistake' becomes a happy accident. Every photographer will have experienced a printer glitch. In this case, a printer error message appeared across a photograph of a tree. Rather than simply reject the print as a mistake, the student began a process of reflection and experimentation.

What happens when you can't control photography? What makes a thought-provoking image are imperfections and the 'unexpected'. She continued to manipulate the image in various ways - enlarging, scanning, cropping, re-printing - until she produced a variety of interpretations of the original error. These were then arranged in a three dimensional installation using various supports and materials.

|

* Aimi Aguilar - Year 13, Thomas Tallis School

|

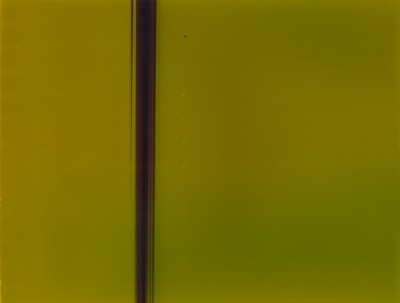

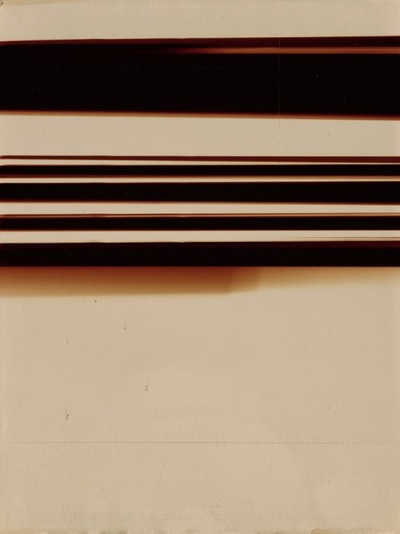

Artist/photographers such as Wolfgang Tillmans have exploited this type of happy accident approach to image making which produces photographs that are the product of chance processes beyond the control of the photographer. Here, for example, are examples from his series of chemigrams entitled 'Silver':

The imaging process is subjected to the inherent logic of the material; it is mostly purely mechanical. The undeveloped photo paper – sometimes exposed to coloured light, sometimes unexposed – passes through a photo-developing machine, which I leave dirty or clean to varying degrees. Because there are remnants of chemicals, diluted more or less with water in the machine, the photo paper continues to develop, though only partially, over time. In addition, dirt and silver particles from the traces of chemicals settle on the paper’s surface, which often produces interesting scratches and brings about a sense of alchemy. Here you are dealing with physical matter on the surface of the carrier in a way that you’ll never actually deal with in conventional photography.

-- Wolfgang Tillmans

Playing Games & Breaking the Rules

The rules (or conventions) of photography have never been fixed but most people have an idea about what makes a successful picture. These features might include, for example:

- main subject in focus

- no obstructions (e.g. finger over the lens)

- straight (rather than wonky) horizons ...etc.

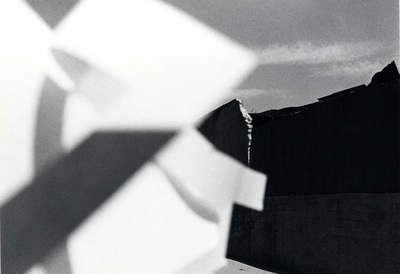

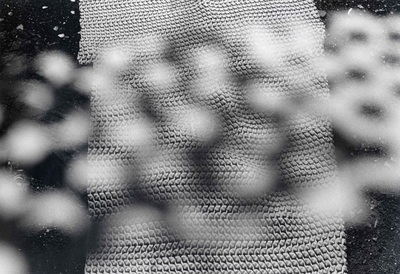

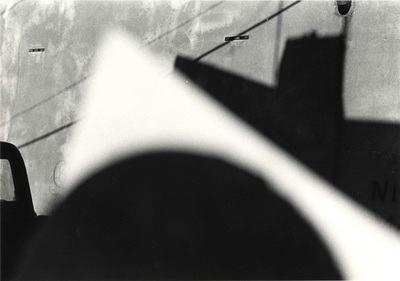

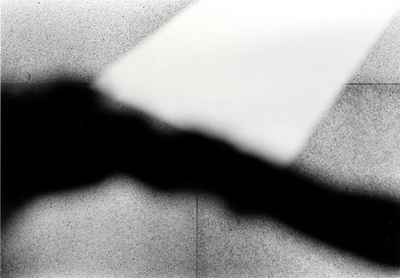

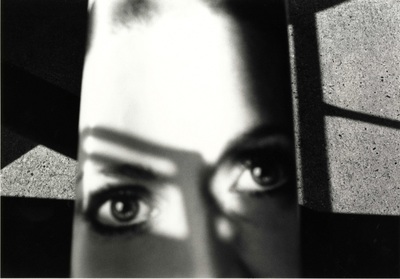

Metzker's interruptions

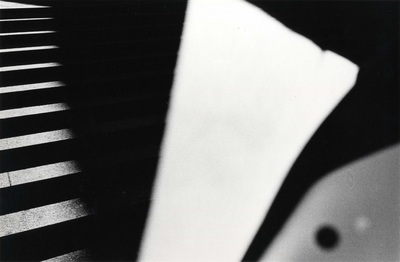

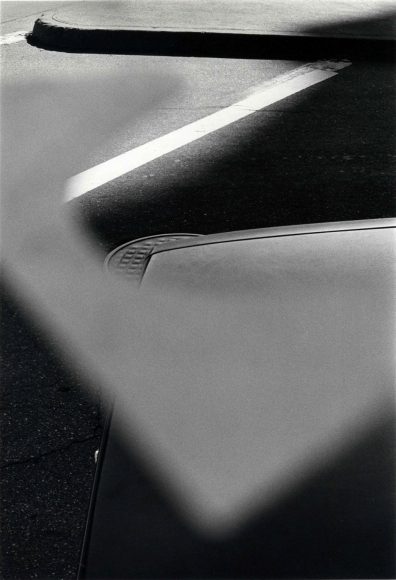

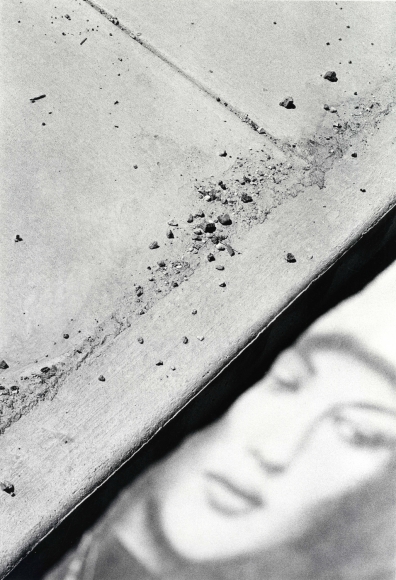

Ray Metzker's approach to photography was forged at the Institute of Design in Chicago, dubbed the New Bauhaus. Here he learned how to experiment with the medium of black and white photography, testing its boundaries and pushing it to its limits. He experimented with composites, multiple-exposure, superimposition of negatives, juxtapositions of two images and solarisation. His work is about vision, light and shadow, abstraction, the peculiar way that photography represents reality and surprise. In the later 1970s he began the series known as Pictus Interruptus:

It becomes clearer...that I am looking for the unknown which in fact disturbs, is foreign in subject but hauntingly right for the picture, the workings of which seem inexplicable, at the very least, a surprise.

-- Ray Metzker

Metzker is experimental, restless, and brilliant—a street photographer who sees the world in fragments and distortions. “Pictus Interruptus,” the black-and-white series shown here, is especially disorienting, each image a cleverly unbalanced mixture of in-focus and out-of-focus elements, including pieces of paper thrust before the lens. The resulting abstractions render the urban landscape almost unrecognisable—a fun house you wouldn’t mind getting lost in.

-- Vince Aletti

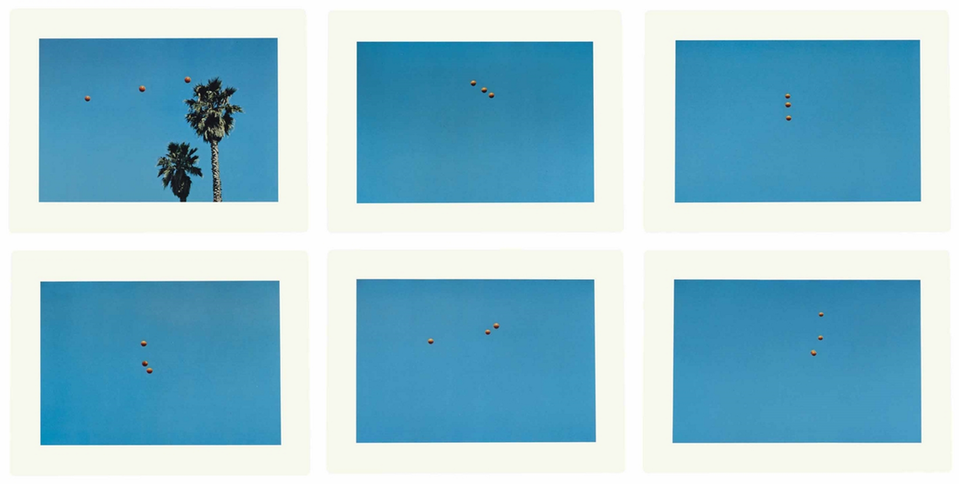

Baldessari's balls

John Baldessari takes a sardonic approach to game-playing, chance and failure in this famous set of images from the early 1970s which were bound into an artist's book. Baldessari's practice is conceptual in that the aesthetic appearance of the photographs is of secondary importance to the idea driving the project. Nevertheless, the choice of orange balls set against the complementary blue of the cloudless California sky is clearly not entirely the product of chance.

The artists' book, Throwing Three Balls in the Air to Get a Straight Line (Best of Thirty-Six Attempts) (1973) represents Baldessari’s interest in language and games as structures following both mandatory and arbitrary rules. Baldessari attempts to fulfill a simple yet arbitrary goal, following rules in a similar manner to a game as structured by the title of his book. There are thirty-six documented attempts in the book - the typical number of exposures on a roll of 35mm film. The resultant images are documentation of Baldessari’s game, but they also border on abstract imagery and bear a resemblance to his later works involving painting or placing brightly colored circles over faces in appropriated photographic imagery to obscure the subject's identity.

-- MoCP website

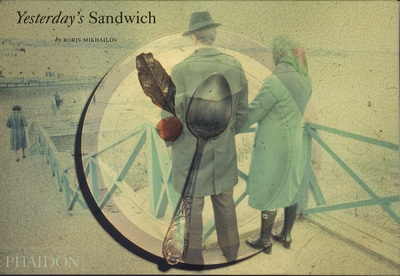

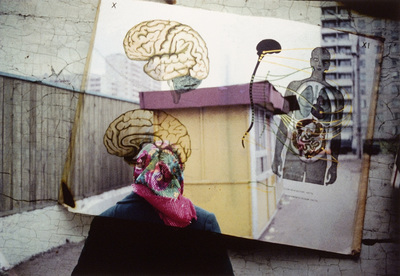

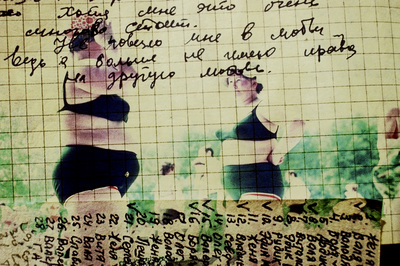

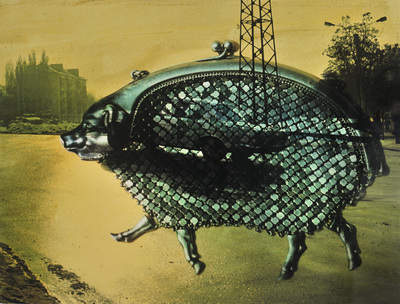

Mikhailov's sandwich

Boris Mikhailov is now respected across the world for his often searing images of Lithuania under communist rule. His approach to photography is fundamentally experimental. He is self-taught and photography was often a dangerous activity under state censorship. His pictures are often subversive and a direct challenge to repressive government. The series of superimposed slides titled 'Yesterday's Sandwich' recently emerged after 50 years in book form. In each case two images have been literally sandwiched together to reveal a new composite picture. The photographs record casual, artless scenes from everyday life, bits of text and mundane objects. And yet, when combined, these ordinary scenes become extra-ordinary, transformed into dream-like juxtapositions.

Photographic accident may be more interesting than a consciously constructed collage.

-- Boris Mikhailov

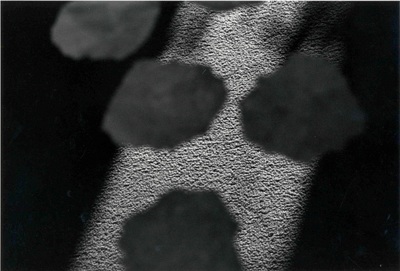

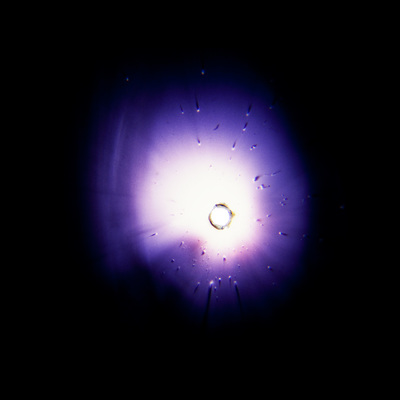

Wright's Coronae

Andrew Wright is a Canadian artist who experiments with photographic processes and images. His series Coronae from 2011 depict what appear to be bursts of light surrounding planetary forms in deep space. In fact the images are made by the artist drilling a hole through a film canister and leaving it in the sun for a while before developing the negatives. The resulting photographs bear witness to the trace of the drill and light itself becomes the subject of the work.

With the ones nearest the surface you get an explosive pattern; the ones closer to the spool are more subtle [...] I really like the push/pull between the microscopic and the macroscopic, that the image could be stellar or the forms could be cellular [...] The colour is just about the way the light shifts and bends and reacts with the emulsion. I have no control. It is completely arbitrary [...] I love the idea that this work is actually a flattening as well as a perceptual collapsing of photographic conventions.

-- Andrew Wright

Suggested activities:

- Ask students to create a list of the 'rules' or conventions of photography - what do they already know about how a photograph should look?

- Reflect on the many ways in which chance can be deliberately invited into the creative process, thereby challenging some of the rules/conventions about photography. For example:

- Can photographs be made by more than one photographer?

- Must the photographer look through the viewfinder before making a picture?

- How might some or all of the decisions about when, what and how to photograph be delegated either to an accomplice or to chance?

- In what ways could photography be conceived of as a game? How might you play photography?

- Ask students to design a photography game as a means to explore their understanding of the role that chance plays in photography.

- Ask students to create a set of images which deliberately disrupt the conventional methods for making photographs, incorporating as much chance as they can tolerate.

Further reading:

The following texts, along with many others, offer further insights into the nature of the intimate relationship between photography and chance:

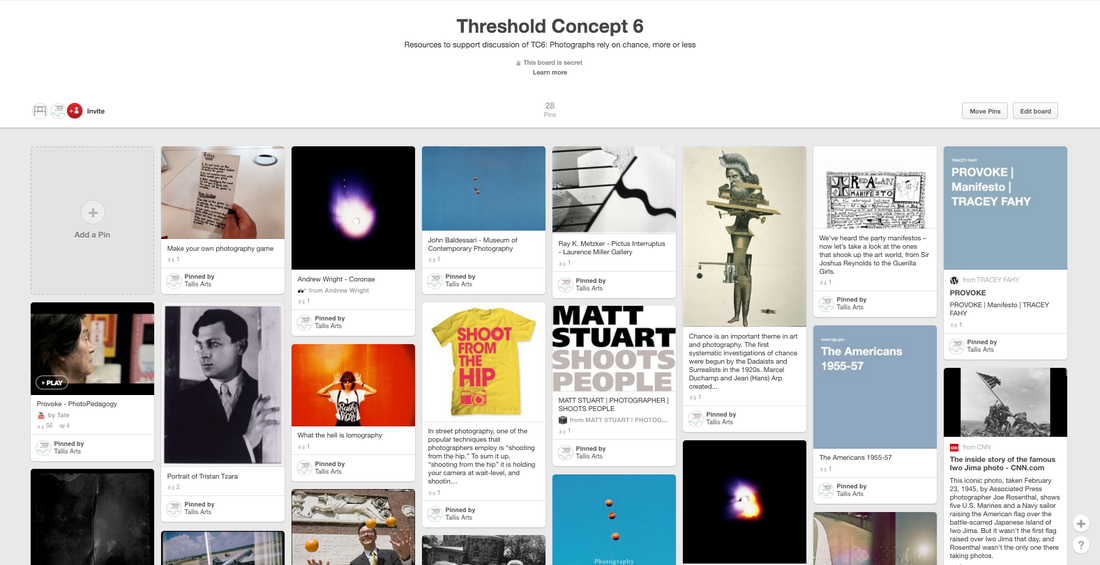

TC#6 on PinterestLinks referred to in this article and others besides are included in this TC#6 Pinterest board. We'll keep adding to these as we discover new resources.

Please use the comment boxes below to share any feedback or thoughts that you might have. |

By Jon Nicholls