|

These resources have been developed in partnership with The Royal Photographic Society (RPS) to support visits to the exhibition Squaring the Circles of Confusion, on from 9 September to 6 November 2022. They are designed with students in mind, particularly visitors aged 11 to 18. However, they can be enjoyed by all and easily adapted for a younger (or older) audience.

The Royal Photographic Society exists to educate members of the public by increasing their knowledge and understanding of Photography, and in doing so to promote the highest standards of achievement in Photography. Click here to discover more. |

|

Teacher Resources

A selection of information, activities and discussion points from this web resource is available to download here. | ||||||

Squaring circles ... confused?

|

To begin, one of the most intriguing aspects of this exhibition is its title: Squaring the Circles of Confusion. The Circle of Confusion is a photography term. It refers to the focussing process. A circle of confusion is created when an image is not perfectly focused. A square might be associated with a pixel (related to digital photography) whereas a circle suggests an analogue point of light. The phrase to square a circle is both a mathematical problem and a common figure of speech. Used colloquially, it describes an attempt to bring two very different things together that would normally seem to be unrelated or separate.

This short YouTube video (right) by The Kinetic Image provides an illustrated explanation to the Circle of Confusion. For discussion: |

|

- Why do you think the curator of this exhibition has chosen this particular title?

- How might an exhibition title influence our expectations of what is on display?

- What kind of photography/artwork might you expect to encounter within an exhibition titled Squaring the Circles of Confusion?

Note: You may need to explore the ideas and issues below before returning to this discussion.

Truth and/or Beauty?

'Beauty is truth, truth beauty,' - that is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

-- John Keats

It might be argued that photography has two parents - science and art - and that photographs can aspire to be both factual documents and beautiful objects. These twin aspirations can be seen throughout the history of photography and are still in tension today.

Photographs are, in part, industrial images, the products of machinery, reliant on the laws of physics and chemistry. They promise an unrivalled accuracy of reproduction, generating a remarkably life-like view of the real world. Photographs are also artificial. They are flattened, abstracted versions of reality, reliant, more or less, on chance and subject to the whims of an individual creator. Throughout the history of photography, the rational, scientific, documentary uses of photography have existed alongside the imaginative, creative and artistic.

As the poet Keats argued, the truthful and the beautiful aren't necessarily in opposition. This exhibition presents the work of several artists who seek a version of the truth through an interest in the beautiful. They are, in some senses, New or Neo-Pictorialists. But what is Pictorialism and what relevance does it have in our digital age?

Photographs are, in part, industrial images, the products of machinery, reliant on the laws of physics and chemistry. They promise an unrivalled accuracy of reproduction, generating a remarkably life-like view of the real world. Photographs are also artificial. They are flattened, abstracted versions of reality, reliant, more or less, on chance and subject to the whims of an individual creator. Throughout the history of photography, the rational, scientific, documentary uses of photography have existed alongside the imaginative, creative and artistic.

As the poet Keats argued, the truthful and the beautiful aren't necessarily in opposition. This exhibition presents the work of several artists who seek a version of the truth through an interest in the beautiful. They are, in some senses, New or Neo-Pictorialists. But what is Pictorialism and what relevance does it have in our digital age?

For discussion:

Our ideas about what constitutes a work of art have changed radically since the mid 19th century. The 'invention' of photography has had a significant influence on the histories of art. Art Photography is now an accepted category but, in the late 19th century, the idea that a photograph could also be a work of art was less clear.

|

Suggested activities:

NOTE: The activities within this resource are designed to be accessible for all and therefore can (mostly) be completed with basic art materials and a digital camera or smartphone. If you do have access to additional resources, for example a wet darkroom, a printer, or software for digital manipulation, then there is potential to adapt and extend many of the suggestions.

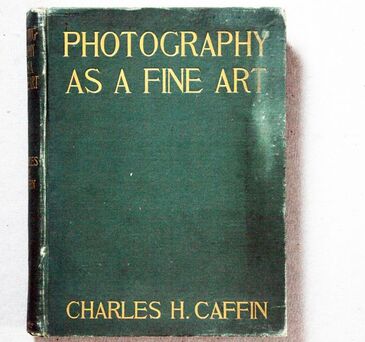

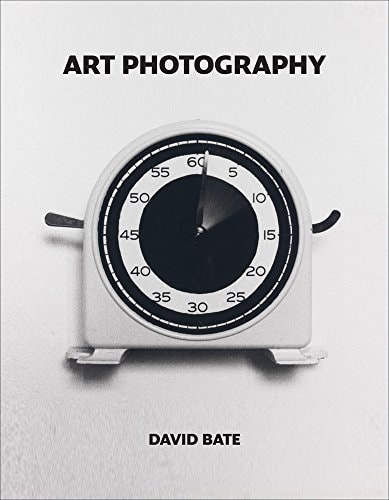

Consider the two books, above, by Charles H. Caffin and David Bate. Only one is accompanied with an image on its cover. Why might this be so, and what difference does it make to your interest? (You may also consider the influence of colours and font styles). Why has this particular image of a darkroom timer been chosen for David Bate's 'Art Photography'?

Portraiture, Landscape and Still-Life are perhaps the key genres that early photography inherited from art. Choose one (or more) of these genres to explore - to help consider the differences between photography and art (such as drawing, painting or sculpture). You might wish to set yourself some guidelines which (even if destined to fail) expose key differences. For example:

Consider the two books, above, by Charles H. Caffin and David Bate. Only one is accompanied with an image on its cover. Why might this be so, and what difference does it make to your interest? (You may also consider the influence of colours and font styles). Why has this particular image of a darkroom timer been chosen for David Bate's 'Art Photography'?

- Create your own alternative cover images. Carefully decide which media or techniques (or combinations) would be best - photography, painting, illustration, collage or something else, perhaps? What type of image, subject matter, composition etc. would best illustrate what you expect of the books (and even the potential differences between them)?

Portraiture, Landscape and Still-Life are perhaps the key genres that early photography inherited from art. Choose one (or more) of these genres to explore - to help consider the differences between photography and art (such as drawing, painting or sculpture). You might wish to set yourself some guidelines which (even if destined to fail) expose key differences. For example:

- Produce a 5 minute drawing, painting and/or sculpture (perhaps using paper, tape, found materials, clay, mud or play-doh). Now attempt a 5 minute recording with your camera. This might be a 5 minute exposure, a five minute video, or a sequence of images taken at regular intervals over 5 minutes. What happens if the time for each response is extended to an hour, or reduced to mere seconds? How might your multiple recordings of the same subject matter be presented in an informative or experimental way?

- Take a photograph - a carefully composed portrait, landscape or still-life of your own staging. Try to make this as true to what you see as your camera allows. Using this photograph repeatedly, create a sequence of images that produce a gradual disruption/abstraction away from the original. For example, your sequence might be created through printing the image 5 times and gradually abstracting what is seen. Alternatively, you might duplicate the image on your smartphone and use basic editing software to create a changing sequence or animation. How might the original image become more (or less) expressive, romantic, painterly, surreal, distorted or disturbing?

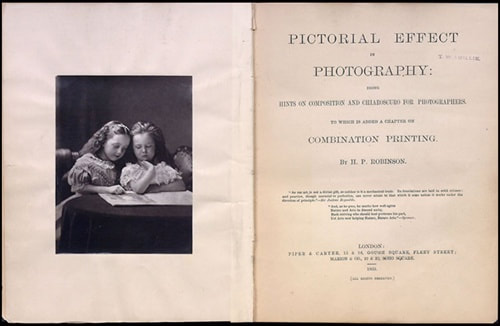

Art, for Photography's sakeONE of the greatest difficulties in writing a book for beginners in any art is to make it simple enough. Nine out of ten photographers are, unfortunately, quite ignorant of art; some think manipulation all-sufficient, others are too much absorbed in the scientific principles involved to think of making pictures. Henry Peach Robinson was an early advocate of the artistry of photography. He helped pioneer combination printing and was critical of photographers for whom a sharp image was considered the height of perfection. He felt that photographers could learn from painters and could create pictures that were interpretations of nature. Robinson's manual advised photographers how to control light and shadow (chiaroscuro) and create pleasing compositions.

|

|

|

Photography has always had an uneasy relationship with painting. By the mid 19th century, painting was a well-established practice with a long history. Painters could belong to academies, were perceived as artists who created unique, high value, collectable objects and could be rewarded handsomely for their talent and experience. By comparison, photographers were often viewed as craftspeople (rather than artists), reliant on technology for the production of their images. Photographs could be reproduced endlessly, were relatively cheap to buy and were perceived as mere 'copies' of nature. By the end of the 19th century, various photographers, with ambitions to create works of art, formed breakaway groups and societies (sometimes with their own exhibitions and publications) in order to champion a new kind of photography. The Photo Secession and Camera Work in the USA, The Linked Ring in the UK, Nihon Shashin-kai in Japan and Austria's Club der Amateur Photographen in Wien are just a few of the international organisations established to promote Pictorialist art photography.

|

Camera Clubs across the world became spaces for developing and refining photographic skills, techniques and processes and celebrating the art (and science) of photography. The Royal Photographic Society is part of this rich history. (Interestingly, the original proposal to establish the new organisation under the Society of Arts was rejected in favour of creating a new, separate Photographic Society.)

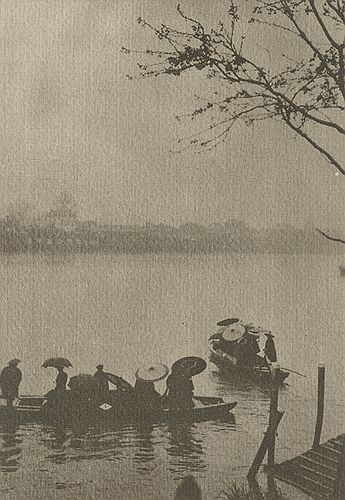

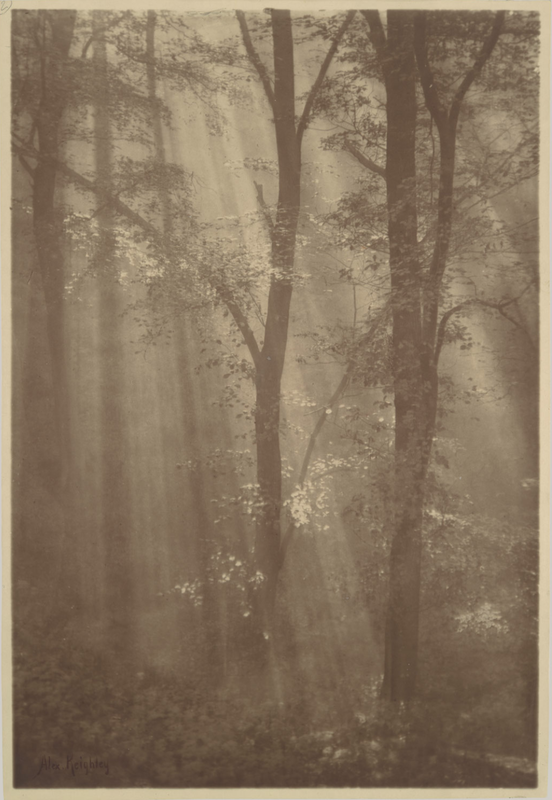

Some examples of Pictorialist photography:

For discussion:

- What qualities do these images have in common?

- What feelings, atmospheres or moods are generated by them?

- Do they remind you of any other non-photographic images?

- What can you discover about the processes used in the printing of these images - platinum, carbon, bichromate, rotogravure/photogravure printing?

- What other printing techniques and processes were favoured by Pictorialists? What 'artistic' effects could they achieve by using them?

Suggested activities:

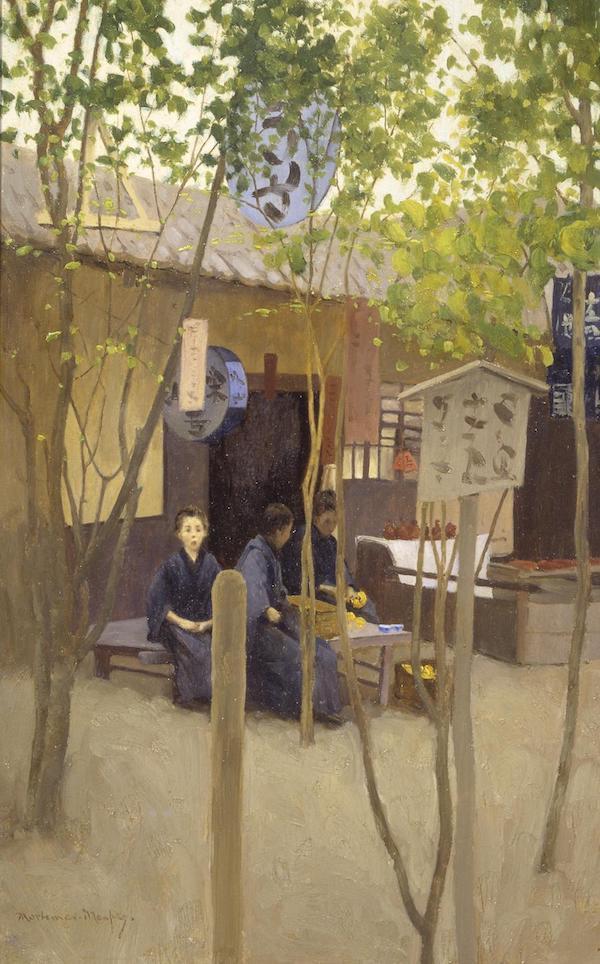

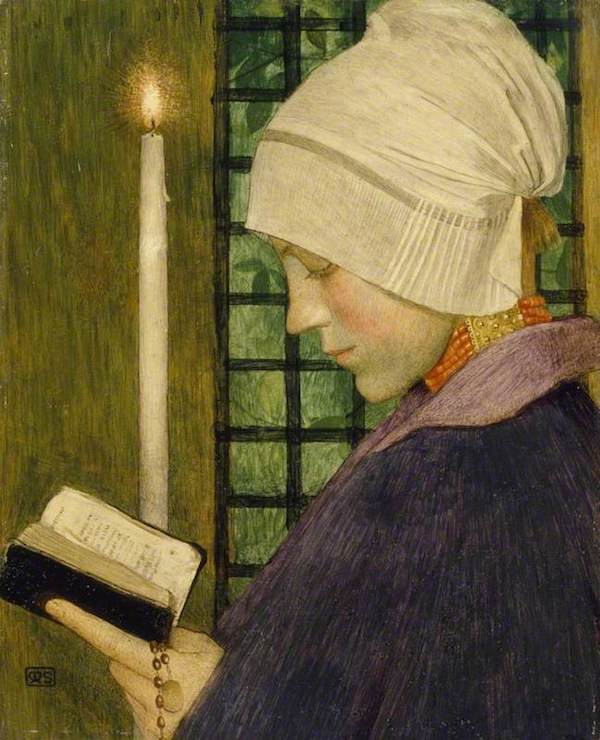

Pictorialism was closely linked to a wide range of artistic movements, both of its time and preceding. Associated art movements and terms include Romanticism, Symbolism, Aestheticism and Impressionism. All these 'isms' can be daunting, but put simply, 'isms' help to categorise - to bring order to particular time-periods, styles, techniques, artistic groups and/or beliefs. 'Isms' might be defined over time or, as has often been the case, in one moment through a damning critical tongue or pen. Artists do not always accept being categorised in such ways and perceptions of art movements are subject to change with time, tastes and experiences. Art Nouveau, Victorian genre painting, the Pre-Raphaelites and Japonisme are further art terms that are associated with Pictorialism. Consider the range of paintings below:

Is it possible to describe and connect all of these images with just one word or sentence - something more revealing than simply 'art' or 'painting' (and less subjective than a sweeping 'boring' or 'nice')? Which words can help to group or distinguish particular paintings? Here are some words to consider: Realistic, abstracted, painterly, dreamlike, impressionistic, symbolic, romantic; composed, cropped, framed, formal, informal, snapshot. Which words seem the most applicable to both painting and photography?

- A potential class/group activity is to print out the various artworks above and also the individual words. You might wish to expand on these with further researched images and additional words. Experiment in groups with ordering and labelling the works. Consider alternative ordering activities, for example: chronological - from the oldest to most recent; matters of truth - from the most realistic to the least; popularity - from the least popular to the most. Share opinions and discuss the challenges of categorising artworks.

- Produce a series of images inspired by one or more of the paintings above. Your series might even incorporate a print or photograph of the painting itself. Your work could be the result of a carefully staged scene and/or model, or alternatively it might be the consequence of an exploratory walk - a dérive in a natural or urban environment. What scene or event might precede or proceed from your chosen painting?

- Choose one of the paintings above (or follow the links to the various art movements and choose an alternative work). Imagine that this was not a painting but a photograph taken by yourself in that particular time, taken on your digital camera or smartphone - a consequence of your ability to time-travel (I did say imagine!). Write or improvise a short account of the experience. Consider the surrounding influences - sounds, weather conditions, atmosphere, tensions. Did you collaborate or interact with someone or were you hidden and discreet? What was your motivation? What were your camera settings/choices and why? What happened next?

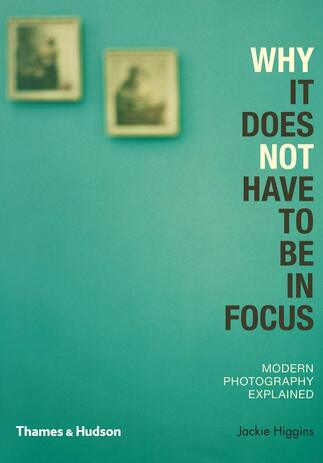

Why it does not have to be in focus

By attempting to create images that looked like paintings or charcoal drawings the Pictorialists have been accused of undermining the distinct qualities of photographs. Photographs could look like fine art but only superficially. Why should a photograph want to look like anything other than a photograph? This raises the question, should photographs look a particular way? What makes a photograph photographic?

This book reveals why a photograph need not be crisply rendered or “correctly” exposed, colour-balanced, framed, or even composed by the photographer in order to have artistic merit. Artists are pushing the boundaries of photography in so many ways that their efforts are arguably redefining the medium. A generation of 'modern' photographers in the 1920s and 30s, proponents of 'straight photography', took issue with the Pictorialists. Central to their critique was the issue of focus. One of the defining features of a photograph, they argued, was its descriptive power and this required sharp focus and a large depth of field. This, in turn, required a small aperture setting so that the subject would remain in focus from foreground to background. Clarity, precision and sharpness (rather than the obscurity, imprecision and lack of focus) were the order of the day. The f.64 group, named after the smallest aperture setting on their cameras, typified this attitude.

But the histories of photography are complex and overlapping. Camera Clubs remained popular, especially with passionate amateurs and, slowly, galleries and museums of art began to accept that photographs should be collected and exhibited. Contemporary artists found new ways to use photography in their practices. So how do contemporary artists relate to the legacy of Pictorialism? And how does their work relate to a visual culture dominated by digital technologies and ways of seeing? |

The new Pictorialists...?

Some contemporary artists/photographers are drawn to the ideas and working practices of the Pictorialists. Whilst they might not accept the label New Pictorialist they represent a renewed interest in alternative processes that subvert the dominance and ubiquity of digital technologies. Sometimes, artists combine digital and analogue technologies in their work. Contemporary artists select from a broad canvas of processes and techniques in order to better express their ideas. Just because a process is officially antique does not mean that it has no relevance to modern experience. Older photographic processes generate images with particular qualities. The process of making these images can be time-consuming, expensive and require specialist knowledge and equipment. The resulting images often have a distinct physical presence. They are objects as well as images and they prompt particular ways of looking and feeling in those who view them. We sometimes think of nostalgia as having negative connotations. It suggests looking back in time with a sense of loss. These artists are looking back in order to look forward. They reject the conventions of modernism, a belief in inevitable 'progress' and technological innovation for its own sake, in order to explore a rich legacy of photographic practices and expand the potential meanings of photographic images. They are forging a link between the past and the present and enriching the language of photography in the process.

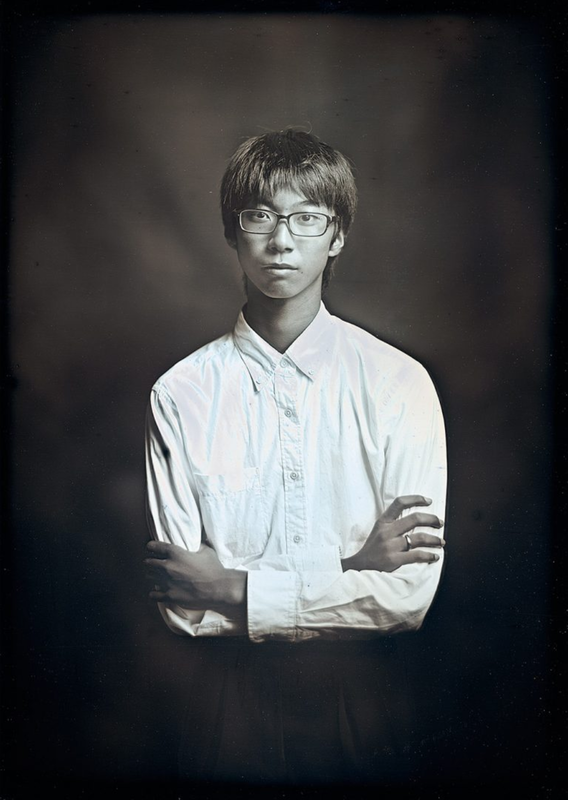

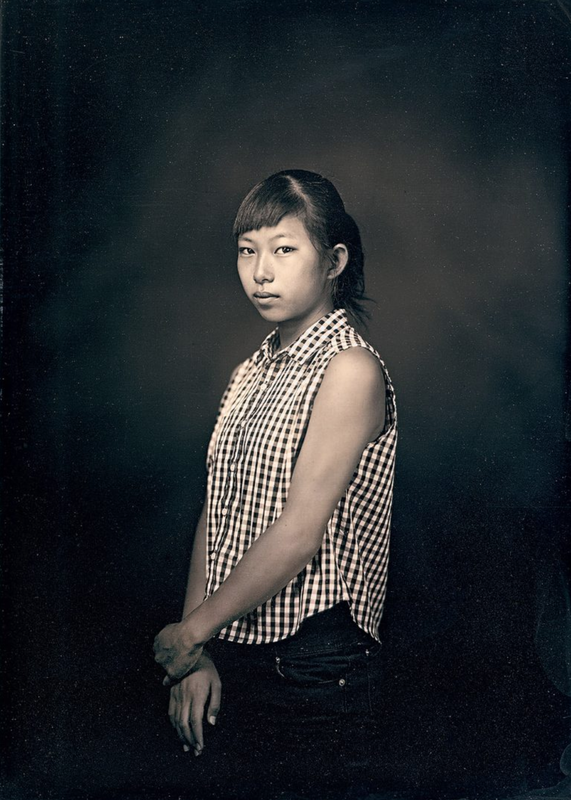

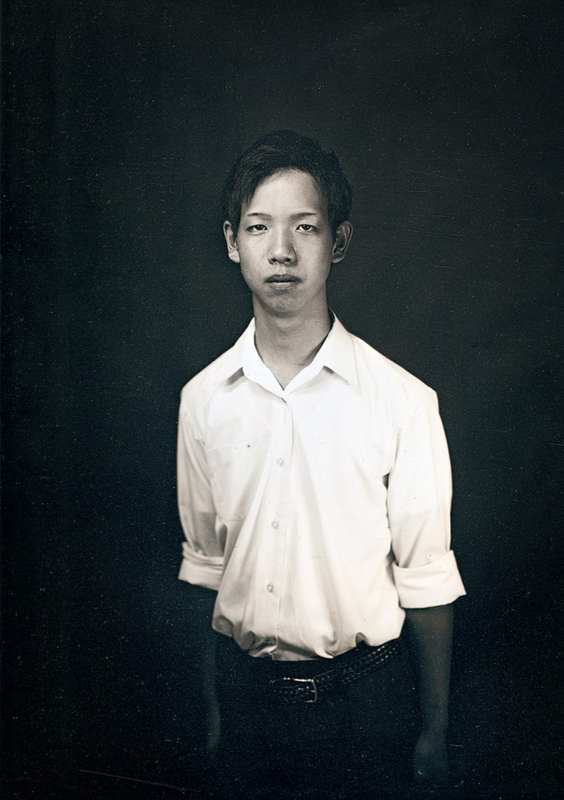

Takashi Arai

|

Inspired by a painting by Kurt Gunther, Takashi Arai has created Daguerrotype portraits of Japanese teenagers.

Tomorrow’s History began with a simple question: “Can we predict the future?” [...] After the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, I was shaken by the helplessly parochial standpoint of this country, which made me want to meet and directly hear what fourteen to seventeen year olds, for instance, were feeling and thinking at the present moment. The Daguerrotype was the first commercially available photographic process launched in 1839. It requires relatively long exposure times and the image has been described as being "mirror with a memory" due to its highly polished, reflective surface in which the image appears to be both positive and negative simultaneously.

|

|

For discussion:

- The title 'Tomorrow's History' seems like a contradiction in terms. What does it suggest to you?

- How much time is contained in each of these photographs? You may want to reflect on all the time invested by the photographer in preparing, exposing and developing each image.

- Why do you think Takashi Arai is so dedicated to such an old, difficult and expensive process?

Suggested activity:

Takashi Arai embraces the Daguerrotype process aware of the presence of layers of time - the history of the process; the time involved in production; the time afforded with his subject as a consequence of the technology. It is this time to gather thoughts and insights from his subjects that Ari seems to particularly value.

- Take a series of portraits of an individual. This might be a family member, friend or perhaps someone you know less well. How can you deliberately slow down the process of taking a portrait to collaborate or connect with someone at a deeper level? For example, you might ask them how or where they would like to be portrayed or informally document them while you have a conversation and a cup of tea together. Alternatively, produce a sequence of images that are taken over a period of days, weeks or longer. Pay close attention to how a person - and your recordings of them - can change with familiarity and understanding.

Susan DergesSusan Derges studied painting before turning to camera-less photographic techniques in order to explore her relationship to nature.

The sun sets, the moon rises, the sea swells and engulfs or withdraws, sustaining these miniature worlds of the intertidal zone. Transient, fragile, colourfully populated dwelling places; sites of memory, continual visiting and contemplating, thought suspended as awareness merges with the water and integrates is own reflection. |

|

Susan Derges, Tide Pool series

For discussion:

- The artist often uses the natural landscape at night as her darkroom. In what ways does the making of camera-less photographs mirror natural processes?

- Derges works with nature to make her images. Chance, therefore, plays an important role in the creation of her images. To what extent do all photographs rely on chance, more or less?

- Noticing the passing of time and deliberately slowing down are important features of Derges' practice. What is your relationship to time when you are photographing?

David George

Like Susan Derges, David George often photographs in fading light. George is concerned with the human-altered post-industrial landscape of the North East of England. His photographs celebrate the personal, subjective encounter with the landscape, what some historians of landscape art refer to as the Romantic 'sublime'. They are reminiscent of certain 19th century landscape paintings. His way of responding to the landscape is therefore quite different to the approach of those associated with the New Topographics.

David George’s night landscapes blur the line between photography and painting; not only because they are conceived as a contemporary reworking of Arnold Bocklin’s “Isle of the Dead”, but because of the plastic qualities that the long exposure grants them. Here, time makes light become movement, and the resulting imprint resembles more a brushstroke than a photochemical outcome.

-- Isaac Marrero-Guillamón discussing the 'Backwater Series' 2012

For discussion:

- The camera is a fantastic tool for describing the world in fine detail. Maximum clarity can be achieved in good, even lighting conditions. Why might an artist be drawn to photographing the landscape in relative darkness?

- Can a motorway bridge be considered beautiful?

- What atmospheres or moods are suggested by David George's photographs?

Suggested activity:

Susan Derges and David George both create evocative work that demonstrates sensitivity to their environment. Their distinctive results inspired by beauty and shaped by technology might be considered as ongoing conversations between photography, time and place.

- Which (safely accessible) locations - natural, urban or less obviously defined - do you have a particular affinity with? Which places hold specific memories or provoke certain emotions? Where have you noticed a particular fall of light or shadow, or a combination of form, colour or texture that might make for an evocative photographic response? Choose a location for a 'sublime' photographic exploration - somewhere that has the potential to evoke a sense of awe and wonder in both you and others via your photographic response. Carefully consider the best times of day, weather and light conditions alongside the most suitable styles, techniques and equipment. Do remember that photography has the capacity to elevate the mundane and seemingly uninteresting. This can be achieved through careful use of light or framing, or even in post-production through digital or tactile manipulation (such as using Adobe Photoshop software or basic editing Apps, or painting or collaging upon printed images).

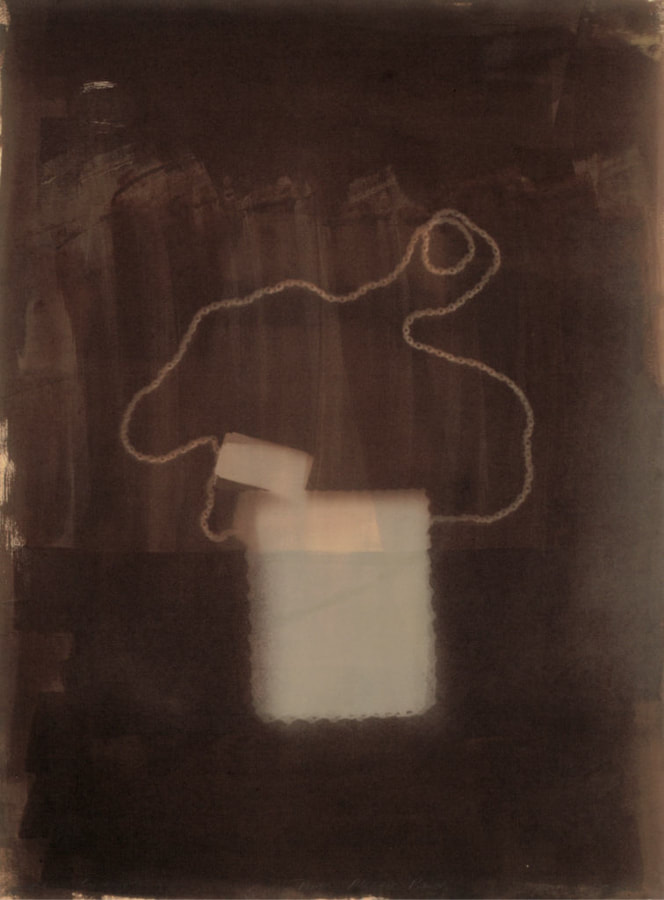

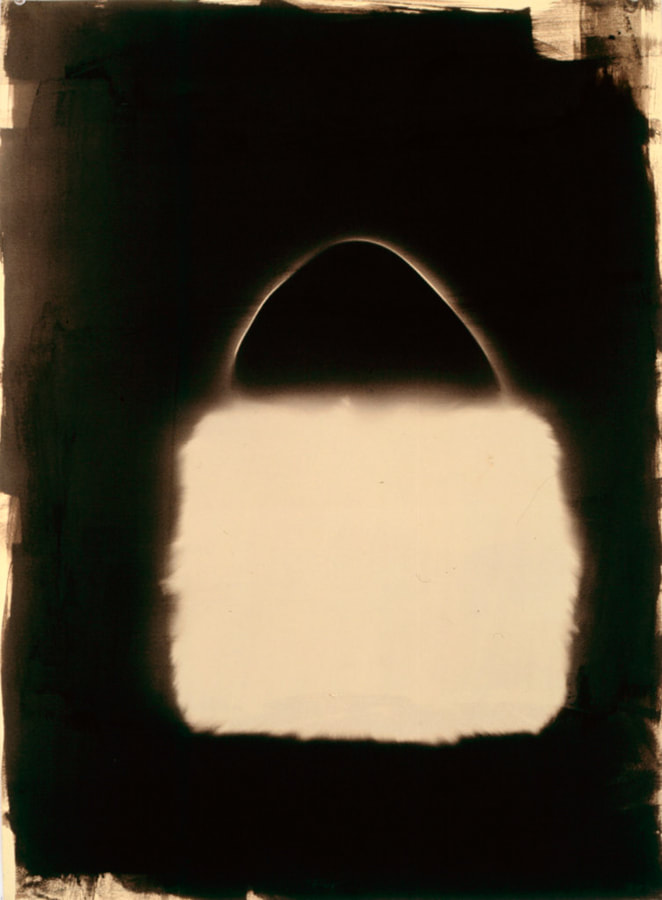

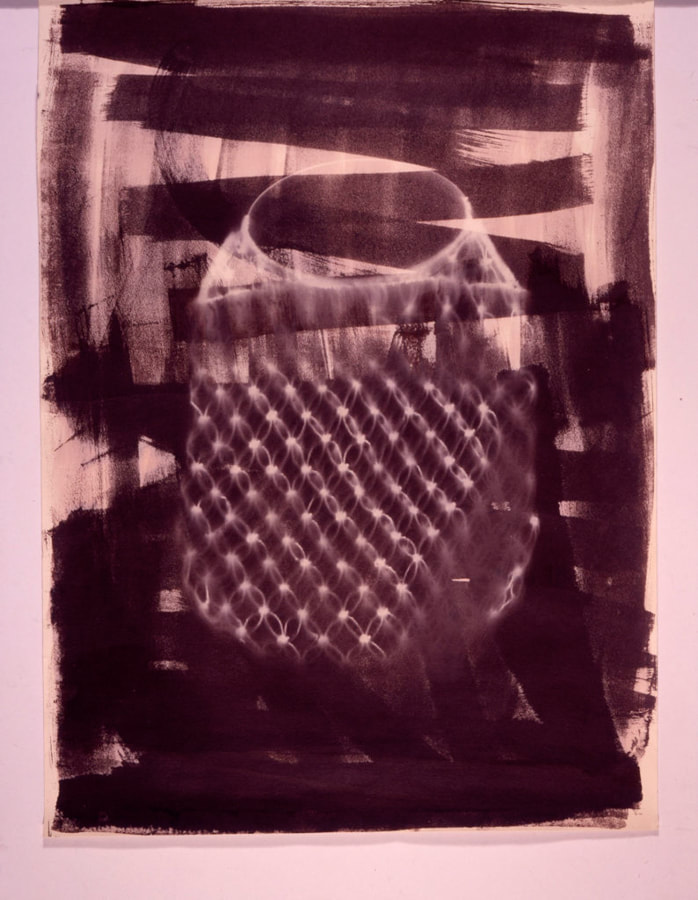

Joy Gregory

Joy Gregory uses a wide range of photographic processes including cyanotype, gum bichromate and salt printing, to articulate ideas about gender and race. These processes were used in the late 19th century by photographers who lived in a world where racial and gender inequality were 'normal'. In 'Lost Histories' and the 'Handbags' series, Gregory responds to a South African context, exploring issues related to colonialism, privilege and the female experience. 'Lost Histories' combines small scale gum bichromate prints and text. The 'Handbags' are salt prints, created outdoors with 10-30 minute exposures, that record the unpredictable interplay of chemistry and sunlight. Handbags are luxury objects, symbols of the advantages of being a white woman in apartheid South Africa and yet still the subject of objectification.

For discussion:

- Joy Gregory uses a wide range of contemporary and antiquarian photographic technologies, processes and materials. To what extent are her choices integral to the meaning of the work?

- Gregory's work deals with complex and difficult subjects - racial and gender inequality, colonialism, personal identity and loss. And yet her images are invariably poetic and beautiful. Why do you think the artist presents challenging images in an aesthetically appealing way?

Tom Hunter

Tom Hunter's practice embraces the links between photography and painting. 'Prayer Places' is a series of pinhole photographs of places of worship in East London. A pinhole photograph requires a relatively long exposure and is a more unpredictable process than using a modern digital camera. The tiny aperture creates an unusually wide angled view in which foreground, middle ground and background are all in focus.

Tom Hunter’s choice to make these photographs with a pinhole camera is critical. It has implications on various levels not only for the construction of the image but also the construction of meaning or interpretation around the image. The pinhole camera is an arcane technology, the most rudimentary of interventions with allusions to the pre and early history of photography and also the artistic ambitions of the Pictorialists. Its use by Hunter might be thought of as subversive in a contemporary era where photography no longer needs to prove itself an an art, an era dominated by digital technologies. |

For discussion:

- Why do you think Tom Hunter chose to photograph these interiors with a pinhole camera?

- What do you notice about the similarities and differences in the various places of worship photographed in this series?

- How would you describe the quality of light in these photographs?

Suggested activities:

Inspired by the work of both Joy Gregory and Tom Hunter, the following activities aim to provide some initial starting points for exploring how photographs capture light (and why a camera is optional).

- Have a go at making a Camera Obscura. A camera obscura is a 'dark room' - a device or construction that can help to demonstrate how light behaves in a camera. You can make a hand-held version or - even better - convert a suitable room in your house or school into a camera obscura. This can be done by taping large sheets of black plastic across the windows and cutting a small hole in the centre. With suitable light outside of the window (and a lack of light inside) you are able to observe the exterior scene projected and inverted upon the opposite wall. Find out more here.

- Have a go at making a pinhole camera. A pinhole camera is a simple camera without a lens - a light-tight box with a tiny aperture (pinhole) at one end and a sheet of tracing paper (or something similar) at the other to enable real-time viewing of projected light and shadows (a pinhole camera such as this might be used for safe observation of solar eclipses). Better still, and with additional photographic resources (a dark room/space, photographic paper, developer, stop-bath and fixer) a pinhole camera (one without a translucent screen) can be used to create an actual photograph. Find out more here.

- Have a go at making a Cyanotype (sometimes also called a sun print or shadow print). A cyanotype is a photographic process that produces a cyan-blue print. This is commonly achieved through placing objects upon a pre-prepared surface and exposing this to bright (sun)light. The process uses two chemicals: ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide. For an easy introduction it is possible to purchase pre-prepared solutions or ready-made paper. Find out more here.

- Have a go at making an Anthotype. An anthotype is an image created using photosensitive material from plants. An emulsion is made from crushed flower petals or a light-sensitive plant, fruit or vegetable. This is then applied to a sheet of paper and allowed to dry. Light obscuring objects, images or materials are then placed upon the paper on the paper and it is exposed to direct sunlight. The parts not covered by materials become bleached out by the sun rays creating a 'shadow print'. Find out more here.

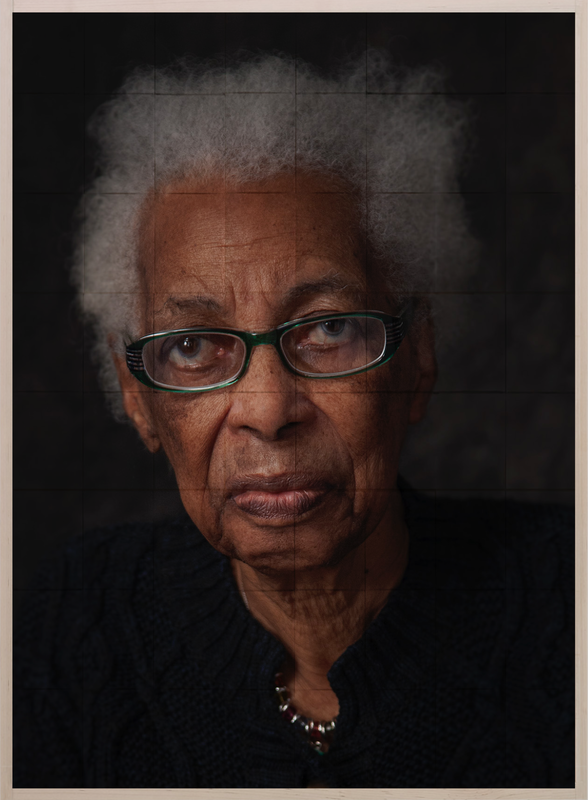

Ian Phillips-McLarenIan Phillips-McLaren is a successful photographer known for his portrait and fashion work. Inspired by Pictorialist photographers like Edward Steichen, he adopted the gum bichromate process. It is a difficult, time-consuming and potentially hazardous, requiring long, dedicated hours in the darkroom and inducing a quiet, meditative attitude to picture making, at odds with the fast-paced, hectic life of a commercial photographer.

His portraits of his mother-in-law Gwen attempt to capture a once strong woman experiencing the onset of dementia. They are constructed from multiple pieces of paper so that the borders and disruptions between each sheet remain visible in the final portrait. “Did I Want To Be Here?” were the last coherent words that Gwen uttered to Ian as he helped her from the car to his house. “Where am I?” asked Gwen. “You’re at Gail and Ian’s for lunch Gwen” he replied. “Did I want to be here” asked Gwen. For discussion:

|

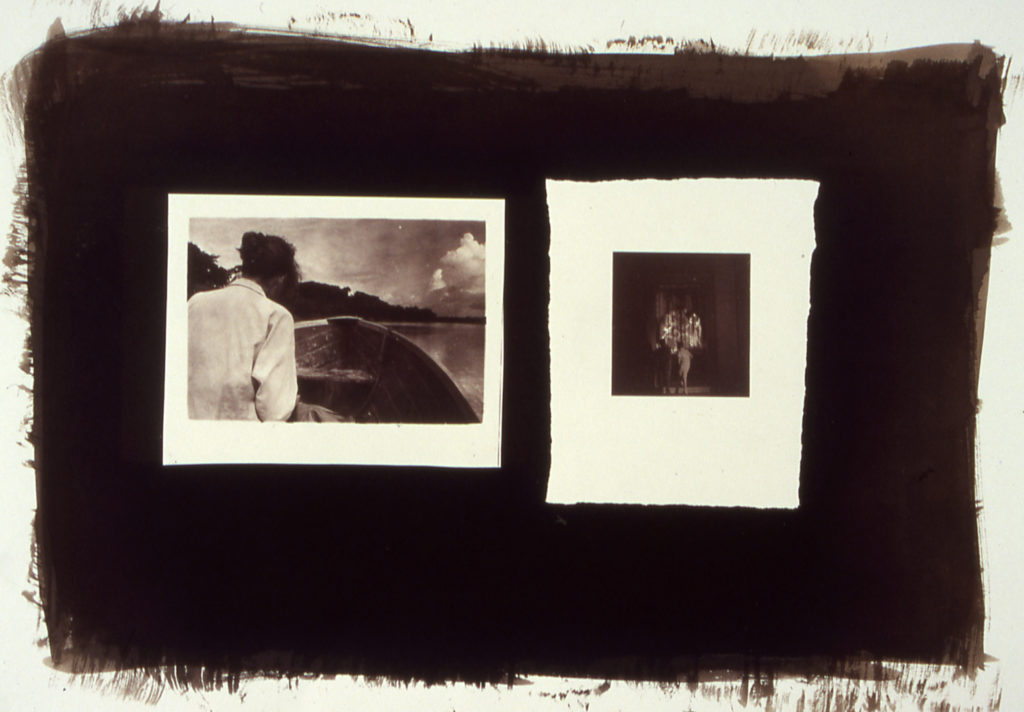

Céline Bodin

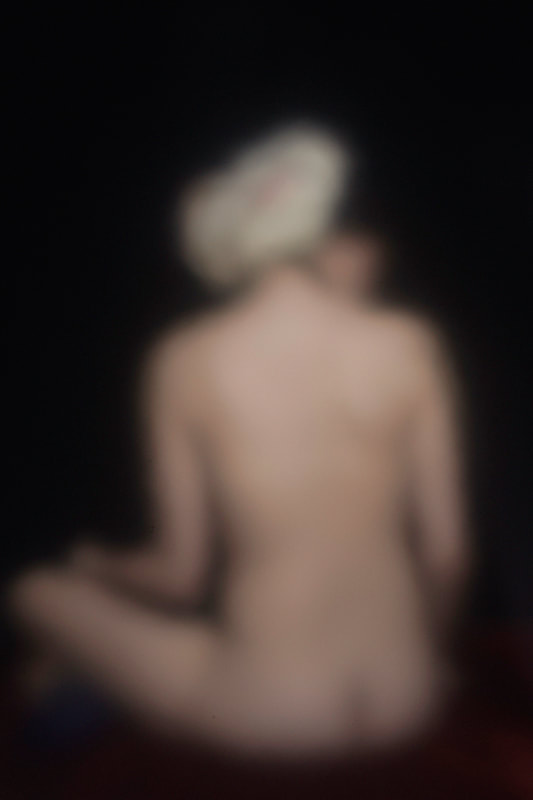

|

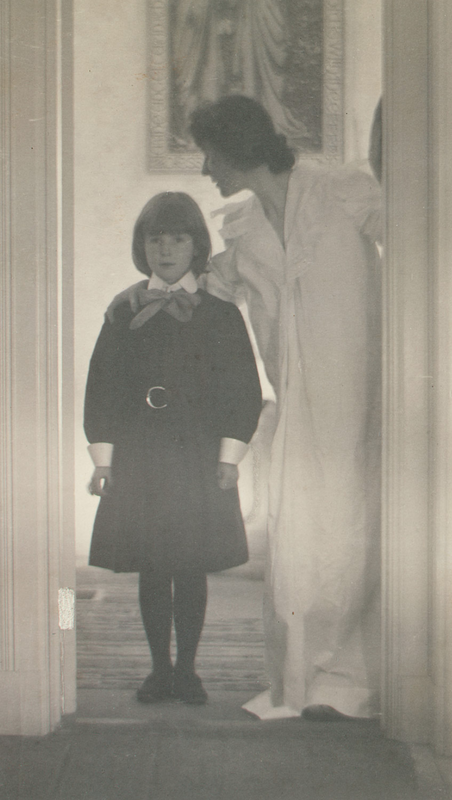

Bodin's images borrow their compositions from 'Old Master' (sic) painting. She uses deliberate obfuscation - heads turned away from the viewer or de-focussing the lens - to enhance a sense of the mysterious or ineffable. She is concerned with presenting the issue of gender stereotypes but in a way which forces us to look carefully and think hard. We are reminded of pictures we have already seen. We grasp for clarity and definition but we are frustrated. The subjects are veiled. Bodin's pictures are in dialogue with the past, with pictorial traditions and notions of beauty, whilst simultaneously offering a contemporary critique.

For discussion:

|

Spencer Rowell

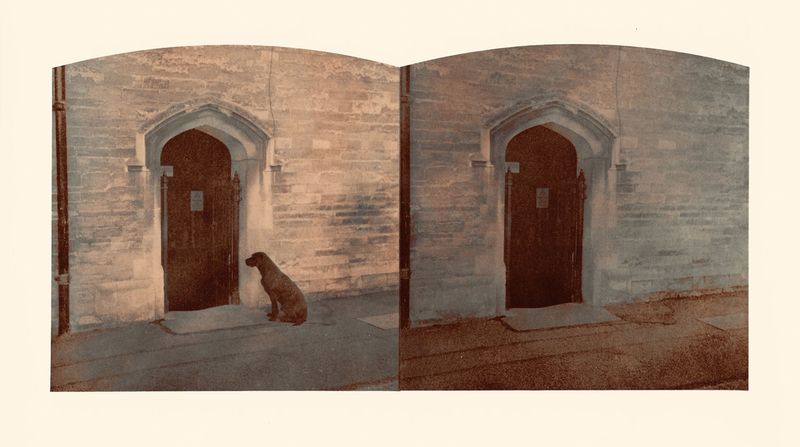

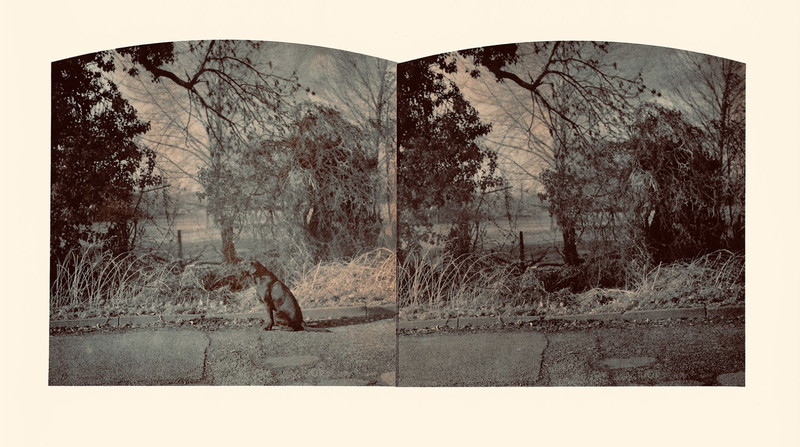

Rowell practices Pathography, an attempt to unite the making of visual art works with psychoanalytic, psychotherapeutic analysis. In the series The Black Shuck of East Anglia, Rowell presents us with stereographs featuring a black dog. Only one of the paired images contains a dog. Presence and absence, life and death, memory and forgetting, alongside the symbolic associations of the black dog of depression and a demonic hound from Norfolk folklore, are all invoked by this image sequence.

From The Black Shuck of East Anglia series, 2019

For discussion:

- Why might the artist have chosen to present the images of the black dog as stereographs?

- The pictures in this series could have been made in the 19th century. Why do you think Spencer Rowell has borrowed the aesthetic qualities of older photographs in the presentation of his work?

Suggested activities:

The diverse examples above by Ian Phillips-Maclaren, Céline Bodin and Spencer Rowell demonstrate the potential of (Pictorialist-inspired) photography to suggest or connect with something more profound. Memories and time, presence and absence, our sense of place and being (or not) are all themes that weave easily through the very nature of photography. Every photograph, whether intentional or not, provides traces of time, presence, absence and place - and as a result has the capacity to influence memory and meaning within all viewers. When photographs are blurred or out of focus, worn, torn, faded or fragmented their capacity to evoke can be heightened further. The vulnerable, mystical and transient nature of photographs is perhaps a reminder to us all of our own fragilities.

How, through photography, might you explore highly personal themes such as memories, inspirations, hopes, fears or your own sense of place - and how might your photographs be developed, manipulated and/or exhibited to emphasise your intentions? For example:

How, through photography, might you explore highly personal themes such as memories, inspirations, hopes, fears or your own sense of place - and how might your photographs be developed, manipulated and/or exhibited to emphasise your intentions? For example:

- If possible, spend some time looking through old family photo albums. Perhaps there is an older family member (such as a grandparent) who can help to explain some of the images. If so, take the opportunity to question them on their own recollections of the circumstances of particular images. How might you re-photograph these images in an interesting way? For example: adjust the focus to emphasise distance (of time); photograph close-up sections to draw attention to easily-overlooked details; photograph older (or younger) hands holding the image, or objects that might connect or contrast with the era or subject matter.

- Take a series of images of a significant place OR a significant person in your life. Rather than a conventional image consider how you might obscure your view to create something more mysterious, dream-like or emotive. For example: create a hole (aperture) in an existing relevant photograph and shoot through this experimenting with focal points; photograph through a clear sheet of plastic or acetate - experiment with creasing, crumpling or smearing vaseline or dripping water upon the surface and holding this in front of your lens.

- Display your experiments in an unconventional location - one that may complement or contrast with your key theme. This could be a low-cost pop-up exhibition, something as simple as a few small prints pinned to a gate post. Alternatively, you might secretly insert your images into an old family album for future discovery.

Suggested Resources:

How does a round camera lens produce a rectangular picture? - Student-friendly online resource from Wonderopolis