Introduction

These resources are designed to support two exhibitions about homelessness, to be held at The People's Republic of Stokes Croft in Bristol, from 25 November to 12 December 2019 and at The Gallery at Foyles in Foyles Bookshop, Charing Cross Road, London, from 13 January to 15 February 2020. Both shows are by Anthony Luvera, an Australian artist, writer and educator based in London.

|

Teacher Resources

A selection of key discussion points and practical activities from this web resource is available to download here. | ||||||

From left: Frequently Asked Questions, Wall installation, Tate Liverpool, 2018; Gerald Mclaverty presenting Frequently Asked Questions at State of the Nation, Museum of Homelessness, Tate Modern, April 2017; Anthony Luvera and Gerald Mclaverty presenting Frequently Asked Questions, Houses of Parliament, June 2019.

First, some questions...

Both exhibitions feature an ongoing project, Frequently Asked Questions, created by Luvera in collaboration with Gerald Mclaverty, a

man who has experienced homelessness. The project was initially intended to provide useful information for homeless people but, when responses from councils failed to materialise, the project became about a worrying gap in the system of social care, further highlighting the challenges facing people experiencing homelessness.

Imagine you are approached by a homeless person in your own neighbourhood. You are politely asked the following questions:

man who has experienced homelessness. The project was initially intended to provide useful information for homeless people but, when responses from councils failed to materialise, the project became about a worrying gap in the system of social care, further highlighting the challenges facing people experiencing homelessness.

Imagine you are approached by a homeless person in your own neighbourhood. You are politely asked the following questions:

FAQsWhere can I go for something to eat or drink?

Where can I find shelter when it is raining or snowing? Where can I go to the toilet during the day? Where can I go to the toilet during the night? Where can I get a bath or shower? Where can I get clothes, footwear, and a blanket? Where can I wash my clothes? Where can I sleep during the night that is safe? Where can I go to use a computer? Where can I go to use a telephone? Where can I go to see a doctor? Where can I go to see a dentist? Where can I access facilities for my pet dog (food, bags for waste, vetcare)? |

For discussion:

- Which questions would you feel fully confident in answering correctly? Which answers would you consider a priority for a homeless person?

- If a homeless person was to put these questions to your local authority, what answers or quality of support should they expect?

- Have you ever considered what it might be like to be homeless in your local area? Where might you sleep during the night that is safe?

Frequently Asked Questions was first presented in 2014 as part of a photography project created with over 50 homeless people in Brighton called Assembly. This multifaceted community-centred project included photographs taken by homeless participants, Assisted Self-Portraits, documentation of Anthony Luvera working with participants, and installation and performance work. The exhibition in The Gallery at Foyles, London includes Assisted Self-Portraits and photographs from Assembly as well as Frequently Asked Questions.

The premise was simple - an email written from the point of view of a homeless person asking questions about access to shelter, medical care, communication facilities, etc. sent to local authorities around the UK. It was initially devised as a way to provide information in the gallery space about homeless support services provided by local authorities around the country. At that time we, perhaps rather naively, thought we'd compile lots of useful information about the services, but were shocked to find that a simple enquiry by a homeless person to the listed points of contacts on the council websites, would be handled in the way it was.

-- Anthony Luvera

Activity:

Frequently Asked Questions demonstrates that even the most seemingly straightforward questions can remain unanswered by those in authority. Why is it that some local authorities (or more broadly, those in positions of power) might fail to respond sufficiently? In what ways might being homeless or poor hinder opportunities for satisfactory answers?

Below are some suggested activities to respond to these issues:

Below are some suggested activities to respond to these issues:

- Which societal concerns - local, national or global - do you feel need addressing? Construct a list of questions and address them to an organisation or individual who you imagine should be able to answer. For example, you might wish to ask questions about your school to the headteacher, questions about climate change policy to the prime minister, or questions about lack of facilities for young people where you live to the leader of the council. How might your questions be represented visually, for example as a set of photographs, a photomontage, or a short film?

- Imagine you are the recipient of your own questions. Research possible answers and create a written or visual response.

- Explore your local area with your camera. Consider how you might take photographs that represent the frustrations of not being listened or responded to. What might you photograph that represents a: dead-end; an endless wait; a sense of vulnerability; a lost cause; a sense of time passing; a lack of control?

- How might you use or share your photography to provoke others into thinking about these issues?

Photographing Homelessness

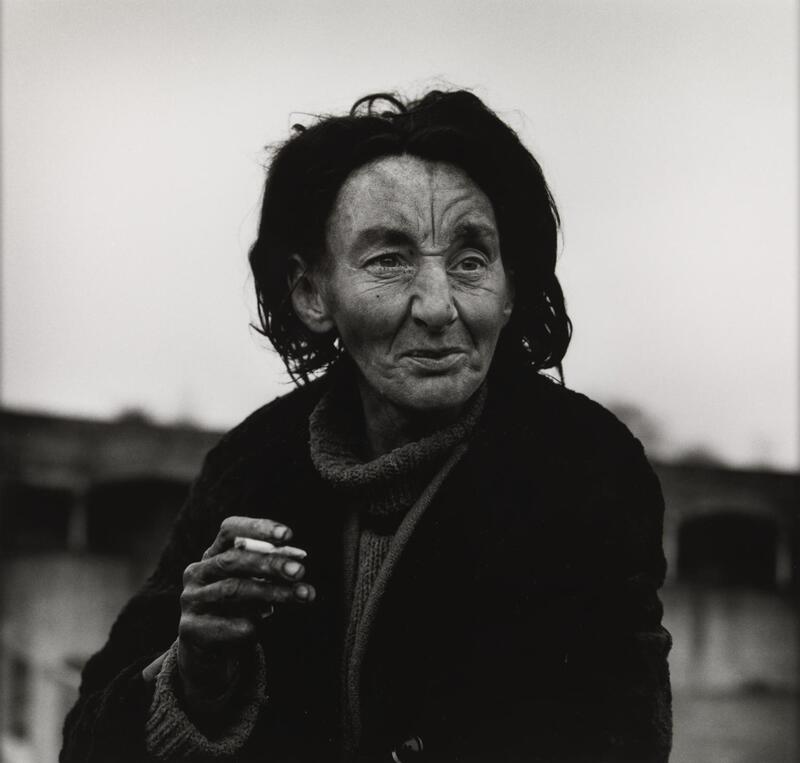

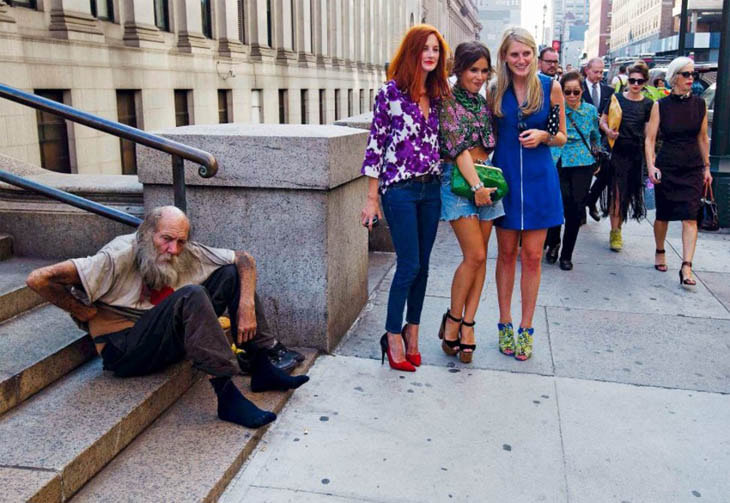

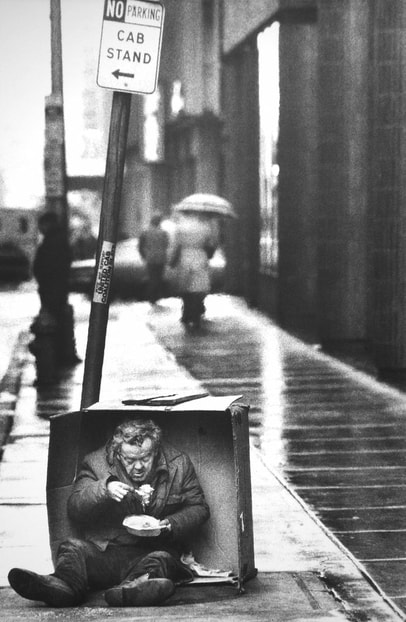

Homelessness is an emotive issue. People experiencing homelessness live on the margins of society and are the subject of public concern. Unfortunately, homelessness is a feature of urban life, an issue all too familiar to those who spend any time in a city. Consequently, those experiencing homelessness have featured throughout the history of photography. The subject has been approached in various ways with varied intentions. So what might motivate a photographer to document those challenged with homelessness, and what issues can complicate this subject matter? Consider the following examples:

For discussion:

- Which of the following words might you connect with specific images: GRITTY, SCULPTURAL, ABSURD, HUMOROUS, POIGNANT, STYLISH, DISTRESSING, TRUTHFUL, CRAFTED, TRADITIONAL, CONTEMPORARY, STAGED. What other words come to mind?

- Which image evokes the most empathy within you, and why? Which do you consider the most thought-provoking?

- Is it okay to profit from a photograph of a person experiencing homelessness? In what ways might a photographer benefit?

Activity

Have you ever photographed a person experiencing homelessness? If so, why, and did you seek permission? From security cameras to encounters with wannabe street photographers, in what ways do you think a homeless person might be photographed or recorded each day? Is it likely that a person experiencing homelessness will have photographs of their own childhood? What might it feel like to have lost (or have never had) photographic evidence of your existence as a child or young person?

- Create a fictional timeline - a fictional day-in-the-life of a person experiencing homelessness. Tell a story via images only found on the internet, or alternatively, take to the streets and try to document life as you might imagine it, through the eyes of someone challenged with homelessness. If appropriating images, don't worry about consistent appearances or likenesses, instead consider how objects, viewpoints, various types of photograph might represent particular experiences or challenges encountered by your fictional character.

- Once you have created your timeline, identify a public space (perhaps a wall, a park fence, a closed-down shop window or a gutter) where you might be able to temporarily set-out, exhibit and re-photograph your images. Do this with respect for the environment, for the benefit of the local community.

Socially Engaged Practice

Photographs do not just record the world around us, they influence our behaviours, actions and understanding. Since its invention - for good and bad affect - photography has played a significant part in shaping culture and societies. So today, how might photographs help us to understand an issue or problem in society so that we can change it for the better? How might photography be used as a way to connect with others - to empower those less fortunate, to instigate action, to bring about positive change?

Socially Engaged Practice describes a deliberate attempt by artists and photographers to empower people to represent themselves, to participate as equals in the process of making images and to have a say in the ways these images are shared with a wider audience.

Socially Engaged Practice describes a deliberate attempt by artists and photographers to empower people to represent themselves, to participate as equals in the process of making images and to have a say in the ways these images are shared with a wider audience.

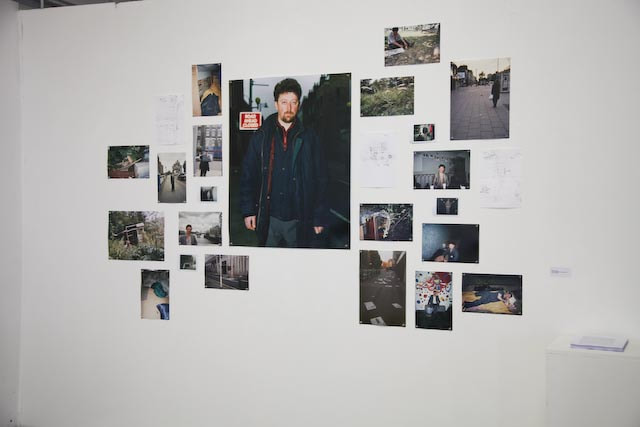

Anthony Luvera's photographic work has been exhibited widely in galleries, public spaces and festivals. He describes his practice as socially engaged. Luvera collaborates with marginalised members of the community, providing cameras so that they may photograph themselves, rather than being documented solely by him. He often acts as a technician, providing support for how to use the cameras he provides. The process of making these collaborative images is also captured, often with single use, disposable cameras, and the resulting photographs are distributed and displayed in unconventional ways. Luvera exposes the ethical issues at the heart of the documentary tradition of photography, the imbalance of power between photographer and subject and the tendency to objectify the 'other'. Socially Engaged Practice describes a deliberate attempt by artists and photographers to empower people to represent themselves, to participate as equals in the process of making images and to have a say in the ways these images are shared with a wider audience.

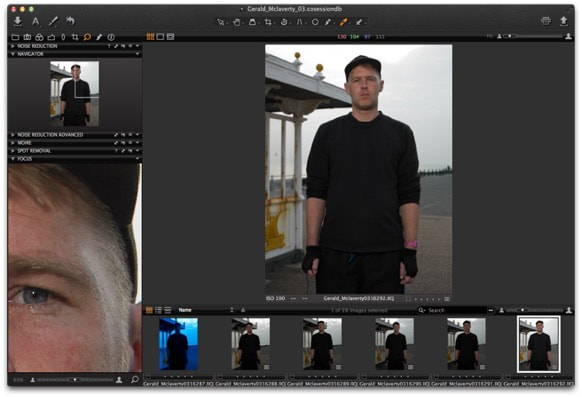

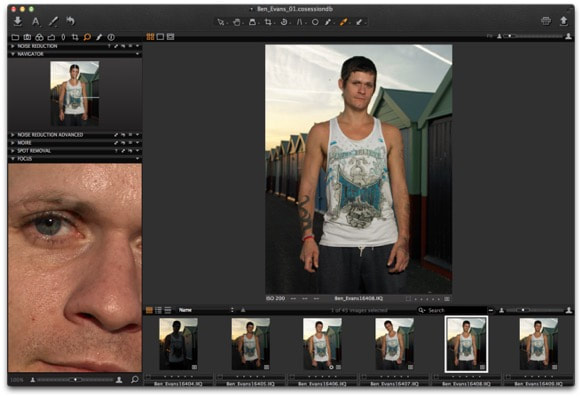

Assisted Self-Portraits

The above images are Assisted Self-Portraits from Assembly. Luvera began creating Assisted Self-Portraits with people experiencing homelessness in 2002. He coined this title to reveal the collaborative nature of the work. The project has enabled Luvera to form positive relationships over time, empowering others by providing a voice through photography - alongside technical instruction and wider support. The term 'Assisted Self-Portraits' has become increasingly applied to this form of social-based practice.

Take a careful look at the range of portraits, above. Now remind yourself of the earlier pictures of homeless people. What do you notice about these images by comparison?

Take a careful look at the range of portraits, above. Now remind yourself of the earlier pictures of homeless people. What do you notice about these images by comparison?

The first time I was a bit apprehensive about it. Thinking like I haven’t took photos of myself before. I don’t really like getting photographed. But then having to do it myself, to me, was … I don’t know. I was just thinking what am I taking a photograph of me for? It’s a bit big headed but I enjoyed it. After the first time it was pretty good. It started getting easier. I felt part of it, so I did.

-- Sean McAuley (from the 'Residency' project 2006-2011)

For discussion:

Consider the two examples below:

- Tom Gralish's photograph won a Pullitzer prize (and $1000) in 1986 for his feature on Philadelphia's homeless. This particular photograph is of a man called Walter. How does Gralish represent Walter in the photograph? Think about the location, the moment captured, the composition, the use of space, the viewpoint etc.

- Now read this commentary by Tom Gralish (below). Does it alter the way you think about Walter and his situation? Are you left with any questions about Gralish's approach to photographing this homeless man?

I didn't know much about these guys. So I decided to show what their day is like. I wanted it to be straightforward 'doc photography.’ Go out and see what you can find. I hooked up with one little group. It was like a community — enough vendors to be nice to them, enough steam grates, a liquor store nearby, a hospital, lots of commuters to panhandle — everything they needed. Walter is one of the guys who is hard to reach because he talks to himself and rants to people on the street. Everyone knows him; people who live and work in the neighbourhood give him change. He was one of those guys who was hot and cold to me. People like it when you pay attention to them. These guys had disdain for society and the rules: that's why they objected to the shelters. They saw themselves as the last free men.

-- Tom Gralish

- Now look at Luvera's 'Assisted Self-Portrait of Ady Baldwin'. How does this image compare with Gralish's?

- What effect is generated by Ady's gaze back at the camera? Who, do you think, selected the location? Who is the photographer?

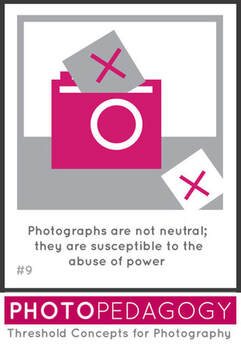

Threshold Concept #9: Photographs are not neutralPhotographs are not neutral; they are susceptible to the abuse of power. Photographs communicate powerful ideas about the world. They can be used to promote both good and bad attitudes. Therefore, students of photography must be very careful to think hard about what they see in other people's photographs and how they make their own. Threshold Concept #9 reminds us of this.

Socially Engaged Practice is a deliberate attempt to tackle the inherent inequality that exists between photographer and subject, especially with regard to portraiture. The potentially negative effects of photography have been highlighted by a number of writers and artists including Martha Rosler, Abigail Solomon-Godeau and Susan Sontag. …there is something predatory in the act of taking a picture. To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them that they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed. |

Activities

- Experiment with the creation of a set of Assisted Self-Portraits. Identify potential collaborators - they could be neighbours, friends, shopkeepers, teachers etc. Explain to them that you are attempting to work more ethically, challenging the inherent power of the photographer and handing over some of this privilege and responsibility to them for making the photographs. Before your subject matter decides how they would like to be recorded, try to forecast some of their decisions. It is very important not to share this or influence their choices, but it might be interesting to compare presumptions and expectations with reality.

- Set up a camera on a tripod and use either a cable release or show the subject how to set the timer in order to make a self-portrait, and/or

- Ask your subject to create a self-portrait with their phone using the front facing camera, selecting the location themselves, and send you the resulting image, and/or

- Ask your subjects to direct you to take their self-portrait, selecting the location, pose, clothes, props, lighting etc., thus limiting your role to that of a technician who follows instructions and releases the shutter.

- Devise an alternative strategy. In what ways might you collaborate and share creative influence? You may want to look at the following projects for further inspiration: Shizuka Yokomizo 'Talking to Strangers', Sophie Calle 'The Bronx', Gillian Wearing 'Signs That Say What You Want Them To Say and Not Signs that Say What Someone Else Wants You To Say'.

- Keep a record of your thoughts to document the process of making these Assisted Self-Portraits. This might be in diary form, illustration or video format. Reflect on how it feels to willingly surrender control to your sitters.

An Expanded Exhibition

|

Anthony Luvera presents complex stories about homeless people and homelessness. Rather than attempt to reduce this complexity to an easily digestible narrative, he carefully considers the format of exhibitions, including images taken at different stages and in different ways, also incorporating audio recordings and other documents.

For discussion:

|

Speaking nearby

Along with a variety of other documents, Luvera often employs sound recordings to help capture a more nuanced record of the process of collaborating with

participants. He has also collaborated with the Choir with No Name who provide opportunities for homeless people to sing together to improve their wellbeing.

participants. He has also collaborated with the Choir with No Name who provide opportunities for homeless people to sing together to improve their wellbeing.

So much of what I do involves getting to know people, spending time together, talking, and listening. I’ve always been interested in the problems of documentary representation and in exploring the potential of finding ways for participants to express aspects about themselves in the work I make. A statement once made by Trinh T. Minh-ha about not intending to speak about her subjects but rather to speak nearby has always stuck in my mind. |

|

For discussion:

Within the quote above, Luvera makes reference to a statement by Trinh T. Minh-ha, a Vietnamese filmmaker and writer. What might she have meant by not intending to 'speaking about' her subjects but rather 'speaking nearby'?

Threshold Concept #7: Context is everythingThe meanings of photographs are never fixed, are not contained solely within the photographs themselves and rely on a combination of the viewer's sensitivity, knowledge and understanding, and the specific context in which the image is seen. Photographs, are polyvalent - their meanings are hard to pin down and one photograph can mean many different things to different people. Threshold Concept #7 reminds us of this.

When photographs are placed next to other photographs and texts, or alongside moving images and sounds, their meanings are multiplied. Printed photographs look different to those projected on a wall or backlit on a screen or lightbox. It is important to consider the decisions taken about how to exhibit or install photographs. These decisions can have a big influence on their potential meanings. I consider all of the material that I have gathered, including sound recordings, as part of the archive [...] I think taking the use of sound recordings further might enable other dimensions of the work to come forward—not only in terms of recording the participant’s intentions, descriptions, and ambitions for the photographs they make but also to represent the dialogues we engage in and to depict other dimensions of who they are and our process of working together. |

The presentation below shares insights into Luvera's collaborative process. Consider the various ways in which images and sound combine to tell complex stories:

Everything inherently has a politics that resides within it … One of the things I strongly believe in is that everyone already has a voice. Some people are in a position to be able to articulate their views in ways in which it will be heard.

-- Anthony Luvera

Activities

- Make a list of issues that concern you. This could be a personal issue that affects you directly, or a more politically charged issue like homelessness or climate change. Consider how you might document your feelings about these issues using a variety of images, films, texts and sounds.

- Once you have compiled your 'archive', think about how you might present a range of different material as an exhibition or collect it together in multimedia form (a bit like Luvera's 'Assembly' film above).

- Where would be the best place to share your work? You could host a pop up exhibition in a public space. Alternatively, you could create a space online (via social media, a blog or website) exploring ways to attract an audience.

Further information

Follow the links below for support and further information regarding issues of homelessness.

How to teach ... homelessness - designed for teachers by The Guardian newspaper and containing a wide range of great resources.

Centrepoint - Centrepoint provides housing and support for young people in London, Manchester, Yorkshire and the North East and through partnerships all over the UK.

Shelter - Shelter campaigns for, and supports those struggling with bad housing or homelessness through advice, support and legal services.

Crisis - support the homeless through education, training and support with housing, employment and health. They offer one to one support, advice and courses for homeless people in 12 areas across England, Scotland and Wales.

The Big Issue - an award-winning magazine offering employment opportunities to people in poverty, to a multi-million pound social investment business supporting enterprise to drive social change. For over 25 years The Big Issue Group has strived to dismantle poverty through creating opportunity, in the process becoming one of the most recognised and trusted brands in the UK.

The Museum of Homelessness - Museum of Homelessness (MoH) is a community driven social justice museum, created and run by people with direct experience of homelessness. MoH tackles homelessness and housing inequality by amplifying the voices of its community through research, events, workshops, campaigns and exhibitions. MoH also provides direct support to its community members.

How to teach ... homelessness - designed for teachers by The Guardian newspaper and containing a wide range of great resources.

Centrepoint - Centrepoint provides housing and support for young people in London, Manchester, Yorkshire and the North East and through partnerships all over the UK.

Shelter - Shelter campaigns for, and supports those struggling with bad housing or homelessness through advice, support and legal services.

Crisis - support the homeless through education, training and support with housing, employment and health. They offer one to one support, advice and courses for homeless people in 12 areas across England, Scotland and Wales.

The Big Issue - an award-winning magazine offering employment opportunities to people in poverty, to a multi-million pound social investment business supporting enterprise to drive social change. For over 25 years The Big Issue Group has strived to dismantle poverty through creating opportunity, in the process becoming one of the most recognised and trusted brands in the UK.

The Museum of Homelessness - Museum of Homelessness (MoH) is a community driven social justice museum, created and run by people with direct experience of homelessness. MoH tackles homelessness and housing inequality by amplifying the voices of its community through research, events, workshops, campaigns and exhibitions. MoH also provides direct support to its community members.