Post 16 lesson plan:

Inside/Out: Thinking about the ethics of photography with Abigail Solomon-Godeau, Diane Arbus, Nan Goldin, Martha Rosler, Jeff Wall and others.

From Jon Nicholls, Thomas Tallis School

Some initial questions:

- When is it not OK to take a photograph?

- Should you always seek the permission of your subjects before taking their photograph?

- Does it make a difference whether or not you have a personal relationship with the subject of a photograph?

- Can photographs hurt people?

- Is all photography a form of voyeurism?

- How responsible is the photographer for the way in which a subject is represented?

- How much control can the photographer exercise over the ways in which their images are understood by viewers?

- Can photographs tell the truth?

In her famous essay 'Inside/Out' (published in 1994 in an exhibition catalogue entitled' Public Information Desire, Disaster, Document by SFMOMA), the writer Abigail Solomon-Godeau discusses what she refers to as the inside/outside positions of photographers in relation to their subjects. She refers to Susan Sontag's book 'On Photography', in particular the writer's criticism of the photographs of Diane Arbus who typifies, for her, an outsider perspective which leads to an unsympathetic, objectifying, voyeuristic attitude to those photographed. Sontag sees this as evidence of photography's colonisation of the world, the photographer as "supertourist", fascinated by the weird and wonderful.

|

Take this image by Diane Arbus, for example. Ask yourself the following questions:

Susan Sontag argued that certain forms of photographic depiction were especially complicit with processes of objectification that precluded either empathy or identification [...] Arbus was indicted as a voyeuristic and deeply morbid connoisseur of the horrible. If Arbus' position is outside and the outside position is bad then, by implication, the inside position is good, suggesting an attitude of "engagement, participation and privileged knowledge." This opposition of outside/inside is at the heart of Solomon-Godeau's discussion.

We might want to present this binary relationship as follows: |

Outsidevoyeuristic

|

Insideprivileged

|

However, Solomon-Godeau goes on to question this binaristic view which she sees as underpinning much of the debate about the ethics or politics of photography. In order to show how the situation might be more complicated she wonders about the relationship between photography and truth.

On the one hand, we frequently assume authenticity and truth to be located on the inside (the truth of the subject), and, at the same time, we routinely - culturally - locate and define objectivity (as in repertorial, journalistic or juridical objectivity) in conditions of exteriority, of noncomplication.

-- Abigail Solomon-Godeau

Furthermore, if photographs are the capturing of surface appearances, how does one judge whether or not a particular photograph represents an insider's or outsider's viewpoint? Where does the difference between inside and outside lie? Is it possible to see a photographer's stance (in relation to his or her subject) evidenced in the photographs s/he makes? In order to further debate the issue she explores the work of several photographers/artists represented in the SFMOMA exhibition. Here are some examples for you to consider:

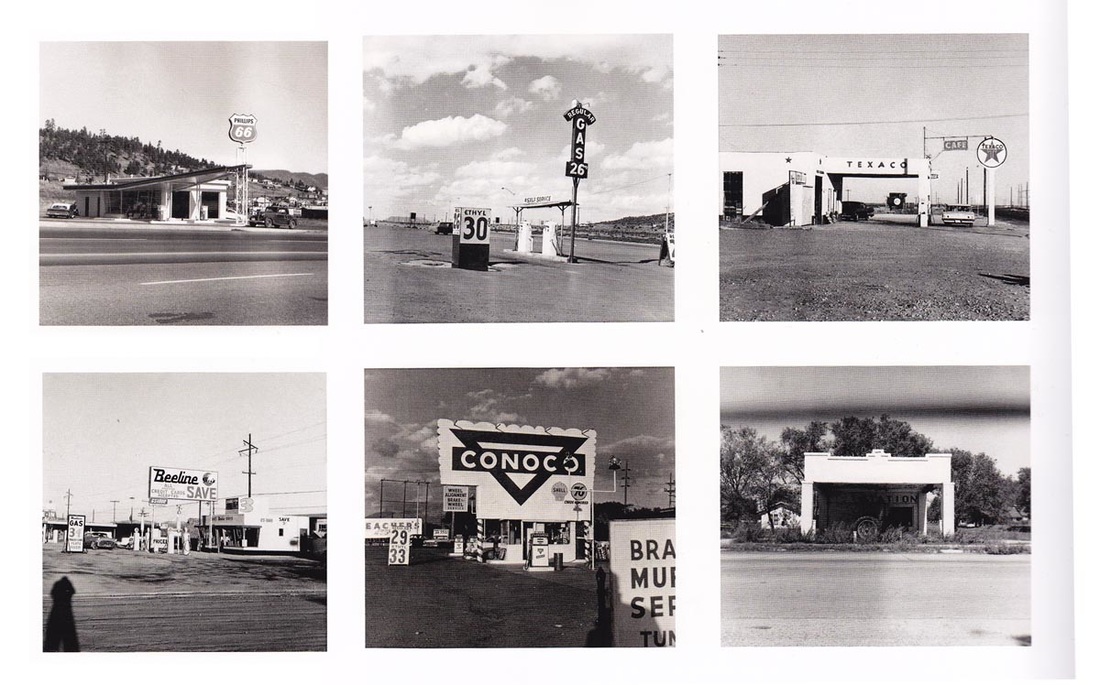

Ed RuschaEd Ruscha's photographic book works [...] or Dan Graham's Homes for America might be considered the degree zero of photographic exteriority. Ruscha's photobooks celebrate the banality of the American landscape, presenting typologies of everyday locations such as gas stations, every building on the Sunset Strip, swimming pools or parking lots. They might be seen to represent "impersonality, anonymity and banality" and thus the outsider's view.

|

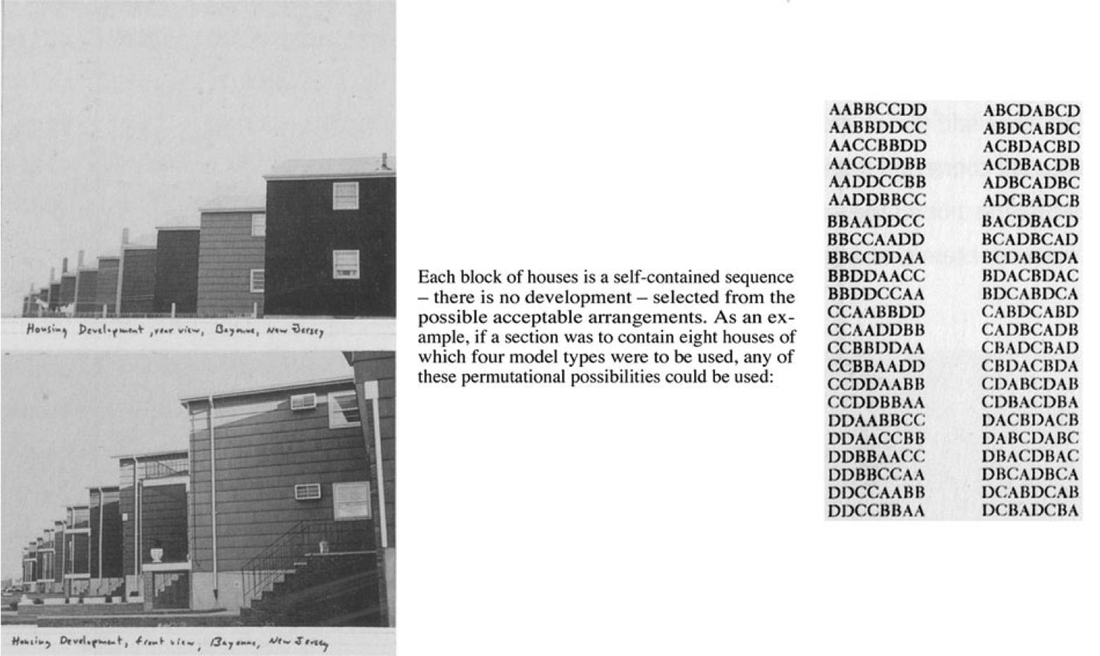

Dan GrahamLike Ruscha, Graham adopted the camera as a tool precisely to embrace the mechanical reproducibility of images. Solomon-Godeau describes this as the "evacuation of subjectivity".

|

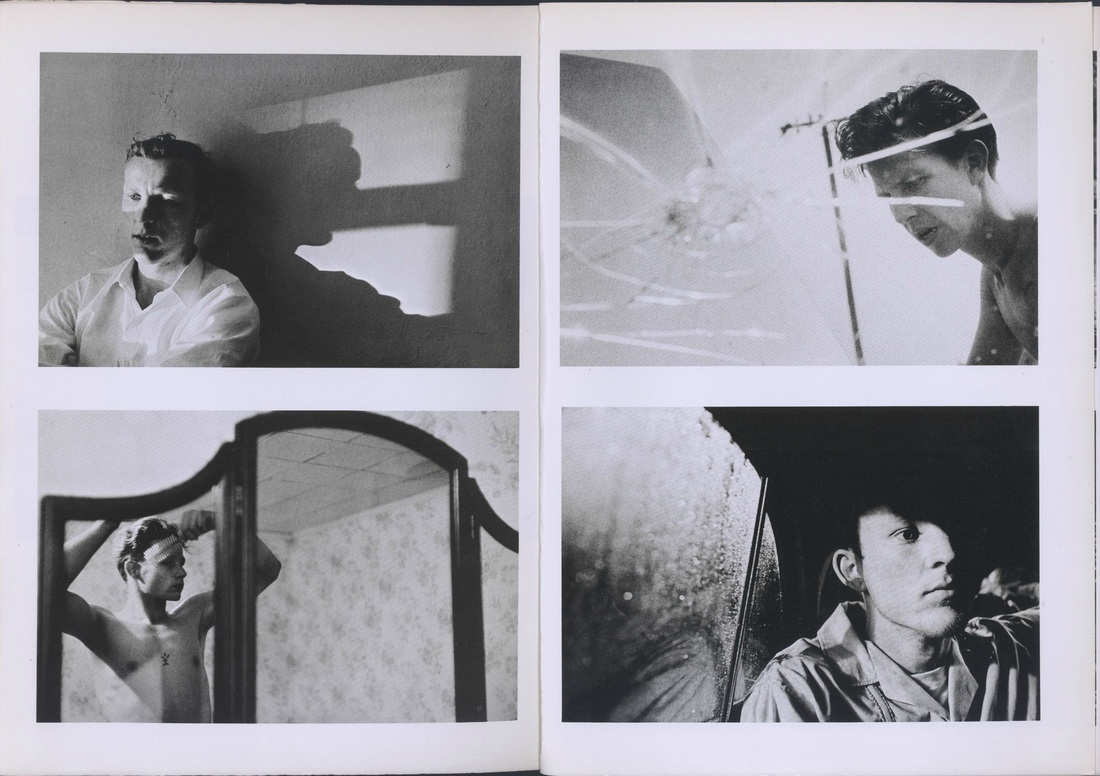

Nan GoldinNan Goldin and Larry Clark represent for Solomon-Godeau the "confessional mode" of lived experience and privileged knowledge in which the photographer has a personal stake in the representation of their subjects, sometimes even appearing in the images themselves.

Their work is compared to that of Diane Arbus in the sense that its subjects are drawn from the margins of society. Consequently, some of the same issues are at stake. To what extent are the subjects a spectacle for the viewer. She quotes Goldin on the subject of voyeursim who claims that, rather than the photographer being the last one invited to the party, "I'm not crashing; this is my party. This is my family, my history." However, regardless of the intimate relationship between photographer and subject, how can the photographer control the reception of these images by the viewer? |

Larry ClarkLarry Clark's photobook 'Tusla' raises some similar issues. Much has been made of Clark's privileged insider position. His photographs of juvenile delinquents document his own gang, the young people he hung out with. The photographer is one of them, so to speak. However:

The desire for transparency, immediacy, the wish that the viewer might see the other with the photographer's own eyes, is inevitably frustrated by the very mechanisms of the camera, which, despite the best intentions of the photographer, cannot penetrate beyond that which is simply, stupidly there. |

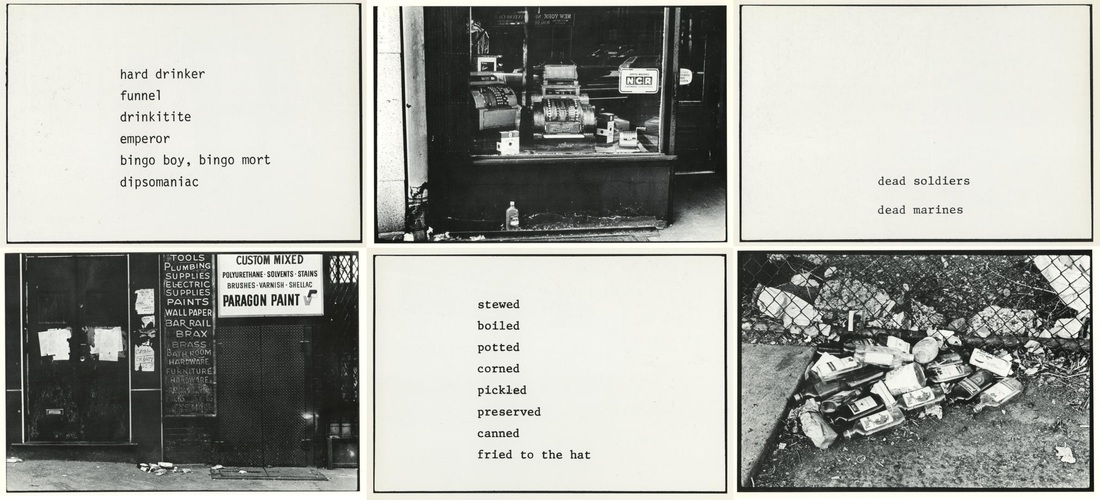

Martha RoslerRosler's approach is presented as an alternative to the binarism of inside/out. Rather than representing the 'other', in this case drunks on the Bowery in New York, the artist juxtaposes photographs of the doorways (in which the men spend much of their time) and panels of text featuring lists of popular slang for drunks and drunkenness. In this way, "by refusing to specacularise the winos" Solomon-Godeau argues that the artist is attempting to unpick the inherently voyeuristic tendencies of all photographs.

|

Jeff WallJeff Wall's practice of re-creating or staging scenes with actors is seen in similar terms.

For all their deceptive realism, Wall's tableaux are entirely theatrical; calculated mise-en-scènes that use actors, locations, and directorial strategies. Solomon-Godeau goes on to question the "truth claims" of photography and the validity of the binarism of inside/outside. In what sense is it possible to represent the truth and how could photography ever claim to be able to achieve a truthful image? Whilst photography remains a source of evidence in police procedure and the courtroom, for example, postmodern artists, in particular, seem to have rejected the idea that photography has any claim to representing the truth.

|

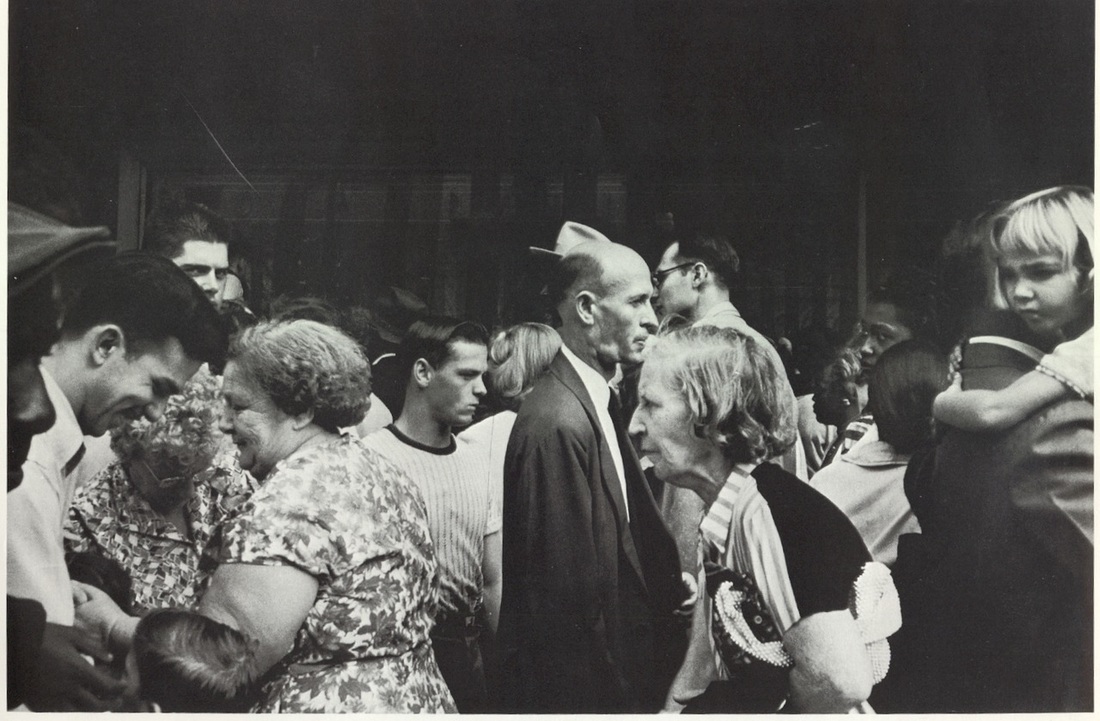

Robert FrankThe essay concludes with the example of Robert Frank. Solomon-Godeau explores the idea that outsiderness, rather than the supposedly privileged inside view, can yield powerful insights. Frank was a Swiss émigré and it could be argued that his outsider status enabled him to perceive the estrangement and alienation of 1950s American culture. Frank's book 'The Americans' captures a truth (if not the truth):

certainly there is truth in its evocation of the lonely crowd, the anomie and nightmare that lay behind the official representations of America purveyed by the media or by corporate advertising. |

Is there a way for photographs to escape the binary of inside/outside? Is it possible for photographs to represent "a truth of appearance"? Is the "truth" always to be found behind surface appearances? What are the limits to photographic seeing? Solomon-Godeau's final sentence offers a mysterious suggestion:

It may well be that the nature that speaks to our eyes can be plotted neither on the side of inside or outside but in some liminal and as yet unplotted space between perception and cognition, projection and identification.

Suggested activities:

- Look through a selection of your own images. Try to decide whether they tend to be views from the inside or the outside. How can you tell? What does seeing them in these terms do to the photographs and your understanding of your own practice?

- Attempt to take a series of photographs of a particular subject having decided before you start whether you intend to adopt an insider or outsider perspective. Look carefully at the resulting images. Were you successful? What strategies did you use in either case? Show your pictures to another viewer. Are they able to tell?

- Attempt to take a portrait of someone you know well. Try to make the portrait communicate some truth about this person. Describe carefully your photographic decisions and the outcome, making sure you incorporate the views of the sitter.

- Take a series of photographs about an aspect of your culture (your local community, your friends, the place where you live etc.) without including any people. Carefully consider the use of accompanying text - titles, captions etc.

- Create an entirely staged photograph about something you have noticed in reality - something you have seen and remembered, an issue you care about, a feeling you have etc. It is important that you have complete control over the resulting photograph, the people, their poses, the backdrop/set, the props etc.

Further study:

|

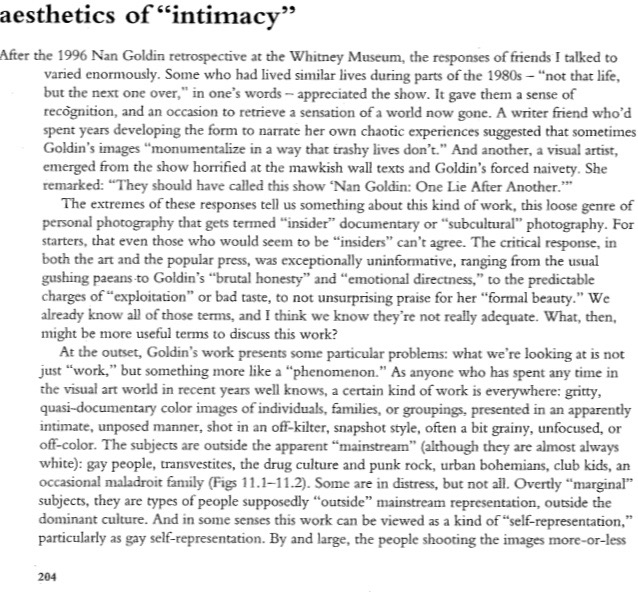

Liz Kotz deals with similar issues in her essay "Aesthetics of Intimacy", with particular reference to Nan Goldin and the 'Boston School'. |

|

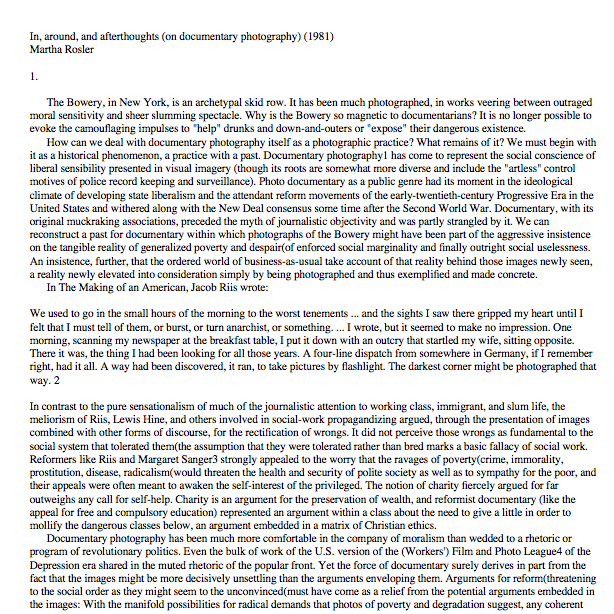

Martha Rosler's essay 'In, around, and afterthoughts' (1981) is concerned with the politics of documentary photography. |

|

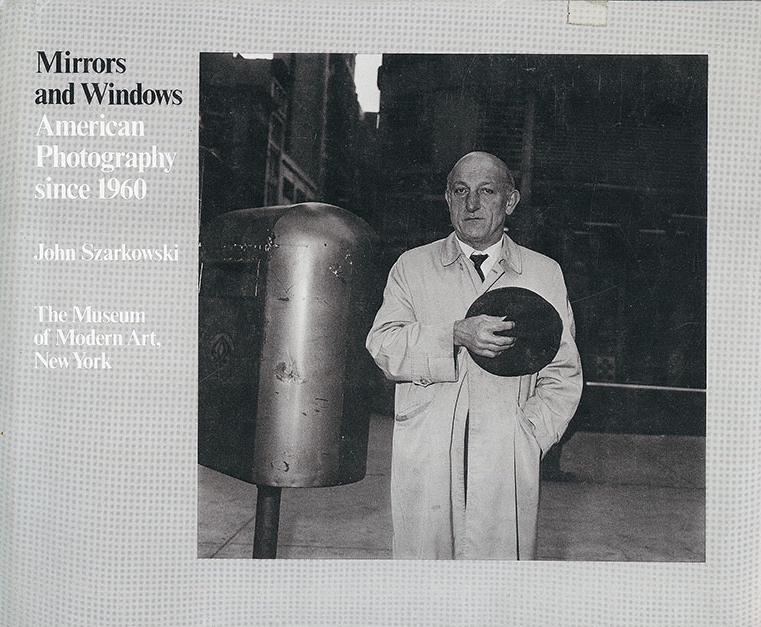

You may also be interested in John Szarkowski's notion of Mirrors and Windows as a way of thinking about the relationship between photographer, subject and viewer.

|