|

These resources have been developed in partnership with The Royal Photographic Society (RPS) to support visits to the exhibition IN PROGRESS: Laia Abril – Hoda Afshar – Widline Cadet – Adama Jalloh – Alba Zari at the RPS Gallery (20 May - 24 October 2021) commissioned by the RPS as part of Bristol Photo Festival. They are designed with students in mind, particularly visitors aged 11 to 18. However, they can be enjoyed by all and easily adapted for a younger (or older) audience.

The Royal Photographic Society is an international educational charity committed to bringing photography to everyone. Founded when photography was in its infancy in 1853, today the RPS is a world-leading photographic community with a membership of 10,700 photographers worldwide. The RPS Gallery is situated in the photography hub at Paintworks, Bristol, UK. |

In progress; a process |

This exhibition is a celebration of contemporary photography at its most diverse, dynamic and progressive. Five distinct solo exhibitions are presented together. Aaron Schuman, the curator, has selected these photographers to collectively represent some of the varied and exciting approaches being taken towards photography now.

Contemporary photography often involves an "expanded" practice - ways of thinking, making and presenting that extend beyond established disciplines and photographic traditions to more fluid and responsive ways of working. Contemporary artists may have a critical or questioning attitude to photography and its histories - a less dogmatic, not-so-fixed understanding of what it means to be a photographer. Contemporary photographers can also be excited by new modes of production and distribution, and new ways to tell their stories. The images on show in this exhibition provide some clues about the direction in which photography is travelling. It makes for a fascinating show for young creatives to explore and respond to. For discussion:

|

The role of research

Every single piece of material present in the project was a tool to support my research, every image was useful in finding the truth [...] Photography can aid in creating a version of reality that helps others to understand. When we are thinking about challenging issues it's often a good idea to do a bit of research. We might have personal associations, prejudices, prior knowledge, theories etc. but research helps us test the usefulness of what we already know. These days, the Internet is invariably where we start. Quite quickly, we encounter this problem: how do we know that what we are reading is true or reliable? Rather than trusting the first results of a search, it's far better to reach wider to test any (competing) claims. In addition, we might turn to books, the knowledge of our friends or family, newspaper articles and pictures. We might even make our own pictures - mind maps, diagrams, drawings, photographs. There isn't just one way to do research.

|

|

Like authors beginning a new novel, contemporary photographers often engage in a process of research before embarking on a project. This might involve a lot of looking and reading. But, sometimes, making photographs is a kind of research in itself. Photographers investigate, explore, compile, map, question, connect, interpret, gather, organise, interrogate, construct etc. Making photographs is part of an extended process of discovery, one way to make sense of things considered, noticed and uncovered. Photography-based research might also involve exploring archival material - old photographs from family albums, news pictures or historical images (such as those held by institutions, for example). Sometimes, when information is elusive, photographers make images to fill the void, to help them imagine what does not already exist. Contemporary photographers can be questioning, critical and suspicious of photography; they are aware of the complex relationship between photography and reality. How research is presented can also be influential in its impact - in its capacity to inform, educate, influence and affect. A contemporary photographer might choose to embrace, or even deliberately disrupt established conventions and expectations for the presentation of research (within or beyond photographic disciplines). |

For discussion:

- What is (or isn't) research? What makes one form of research more effective, reliable or valuable than another? Consider these potential forms of research: reading, note-making, conversations, drawing, taking photographs, developing questionnaires, observing, collecting, trialling, comparing, experimenting. Which of these are you most (or least) comfortable with? What other forms of research might an artist do and why?

- Is copying or printing a picture a form of research? If you were alone in an empty room with no materials or additional stimuli, is it still possible to conduct research? If so how, and of what? Does research have to result in learning or (some form of) tangible evidence of action?

- What issues (personal or public) interest you? What would you like to understand better? Make a list and discuss with your classmates the potential ways you might research to find out more. Consider - invent, even - more playful, less predictable ways of researching, exploring and discovering.

- When was the last time you did some research? What were you trying to find out and why?

- Do you think photography can be a kind of research? Why/Why not?

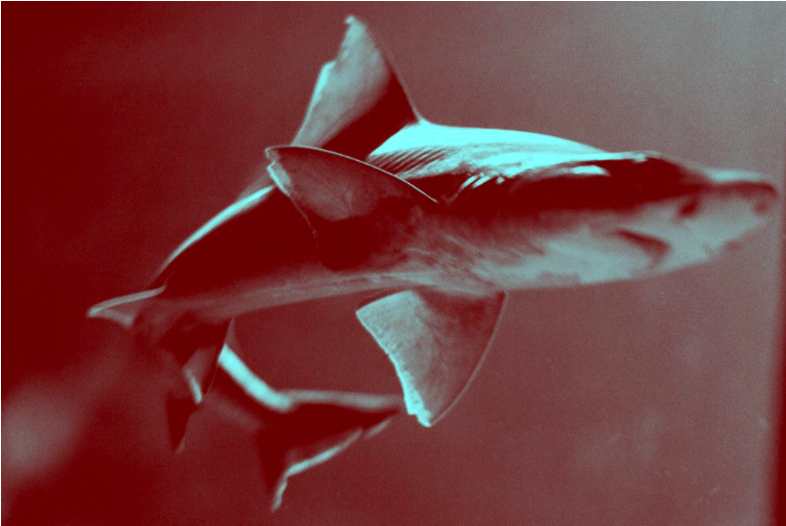

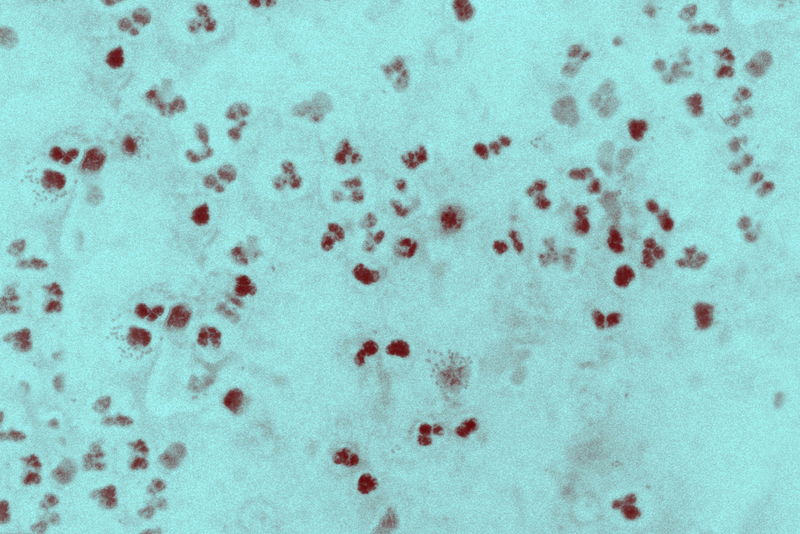

Laia Abril: On Menstruation Myths

Contact with the menstrual flow of women makes wine sour, causes crops to wither, kills scions, dries up seeds in vegetable gardens, knocks fruit from trees, clouds the surface of mirrors, dulls the edge of steel, and tarnishes the shine of ivory, kills bees [...] Abril's work 'On Menstruation Myths' is a chapter of a larger body of work entitled 'A History of Misogyny'. The artist explores the misunderstandings, silences, miseducation and physical pain associated with menstruation. Abril admits to having found the subject of menstruation personally embarrassing. She asks questions about what it means to be a woman, why menstruation is a source of shame, why some young women are denied their basic rights and why myths about menstruation have such deep cultural roots. Abril deliberately creates aesthetically appealing images in order to persuade viewers to spend time with them and read the accompanying text. It is important to her to have both men and women see the work since menstruation is a human rights issue. The combination of blue and red is a kind of visual game since, for many years, advertisers of sanitary products chose blue, rather than red, to indicate menstrual blood. Abril searches for appropriate visual metaphors that synthesise her ideas and arouse curiosity.

|

“Are you sick?” I remember being asked when I was a teenager. People were questioning whether or not I was on my period. Even though I wasn’t supposed to exercise or swim —or apparently make mayonnaise; I never actually perceived those myths as affecting my daily life. However, I remember learning that society had mandated that getting my period should remain a secret. The same ritual that was supposed to symbolize that I had “become a woman,” came with an unbearable pain that was normalised.

-- Laia Abril

For discussion:

- What kind of research has the artist done in order to explore this subject?

- Why is the subject of menstruation such a source of embarrassment and shame?

- What challenges might the artist have faced in choosing to make images about menstruation?

- How has the artist chosen to visually present a potentially alienating subject? Which of these do you find most intriguing, appealing, uncomfortable, effective or informative?

- What are the potential advantages or disadvantages of tackling (addressing, representing, depicting) a subject indirectly - using objects or associated images as visual metaphors or representations?

- Do you think photography has the power to educate and change both opinions and public policy? Can you think of alternative examples where this has happened? What issues or injustices might your own photography explore or address?

- Have your views or knowledge of menstruation been altered by seeing this work?

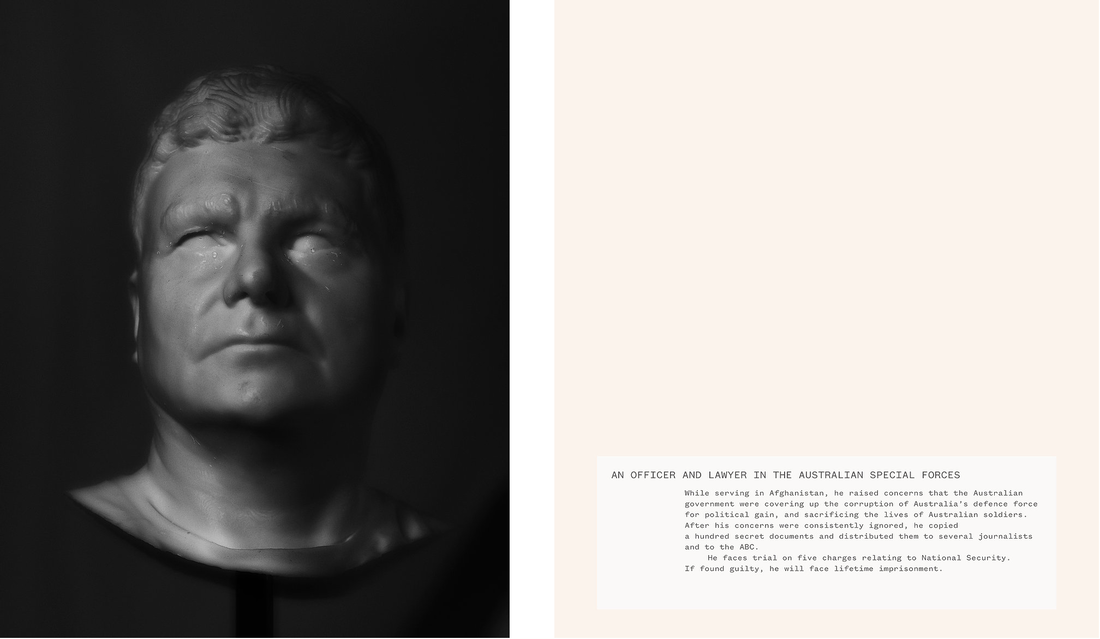

Hoda Afshar: Agonistes

The whistleblower is the modern tragic figure in our current society. For me it was about the character, not the individuals, it was about their actions, and at the heart of it, there was something that reminded me of the Greek tragedies. That’s why I chose the title Agonistes, because this is a Greek word that means personal injury and an inner struggle. The subjects of Afshar's portraits in her project 'Agonistes' are Australian whistleblowers, people who have raised an alarm about a perceived abuse of power, and who are suffering the consequences of their actions. Working with a lecturer in criminology, the artist identified some prominent whistleblowers and photographed them each 110 times in order to create a 360 degree portrait. This was used to generate a 3D-printed sculpture which Afshar then photographed. When exhibited, each portrait is accompanied by an explanatory text.

The process of making the 360 degree portraits, and subsequent sculptures, is not particularly effective in capturing the eyes of the sitters. They become curiously abstract and 'empty' looking. This reminded the artist of the sculpted portraits created by the ancient Greeks. Greece gave birth to democracy and tragedy, two themes at issue in 'Agonistes'. Tragic characters are those caught between opposing forces, often faced with a life-changing decision. This is true of all whistleblowers. Once they have crossed the line, there is no going back, often with tragic consequences. It's also worth noting that the biblical character, Samson, later the subject of a tragedy by Milton entitled 'Samson Agonistes', was blinded by his captors: "Blind among enemies, O worse than chains". |

The trailer for the 20 minute film 'Agonistes' - one-channel digital video, colour, sound.

For discussion:

- Why do you think Afshar chose not to photograph her subjects directly? What risks are involved for both photographer and subject in this project?

- What role does research play in Afshar's practice?

- Why might a contemporary photographer using new technologies choose to reference ancient ideas and methods of working?

- In what ways do Afshar's photographs (of 3D-printed portraits) compare or differ from ancient-classical Hellenistic sculptures?

- What do you notice about the way the sitters are filmed in the accompanying video?

- Why is the accompanying text (caption) for each picture so important?

- Why do you think the artist was so fascinated and troubled by the fate of these whistleblowers? What issues does she expose through the exhibition of these images?

- Have you ever spoken-out regarding an injustice to others; shared a wrong-doing with the hope of positive repair and action? If so, how did you feel? And how would you then feel about being photographed and presented in an exhibition? Why might someone choose to photograph you for this?

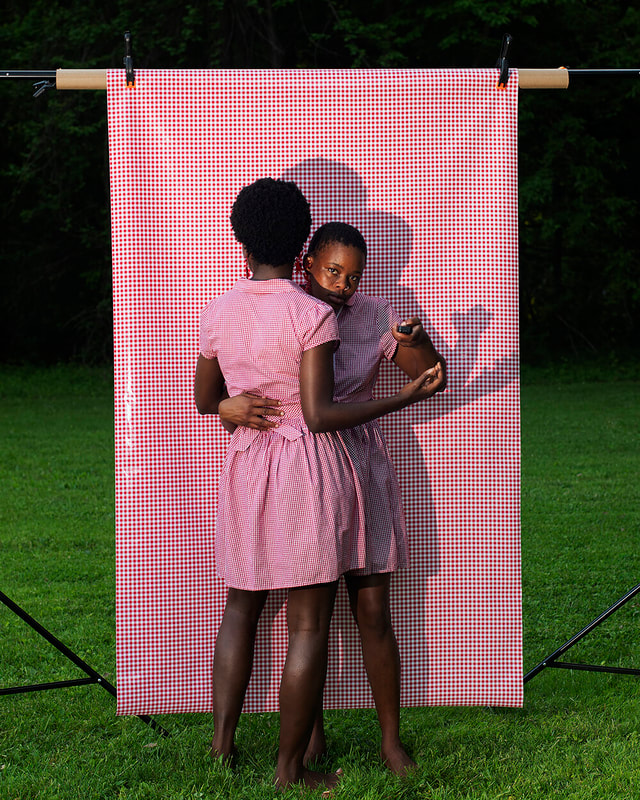

Widline Cadet: Seremoni Disparisyon (Ritual [Dis]Appearance)

Widline Cadet was born in Haiti and lives in the United States. Her work explores cultural identity, race, memory and immigration through photography, video and installation. 'Seremoni Disparisyon (Ritual [Dis]Appearance)' is a series of self-portraits, sometimes featuring Cadet but also using friends and family to stand in for her. Female figures are placed in natural settings. Repetitive gestures, shapes and props tie the images together. Backdrops, poses and an element of abstraction remind us of the constructed nature of photographic images. The pictures are suffused with a warm glow, an idyllic sense of calm and graceful positivity. Women support one another, literally and metaphorically.

Most of the photographs are of Black women and greenery and these abstract landscapes.

-- Widline Cadet

For discussion:

- "Serious hopefulness" is a phrase Cadet has used to describe the intention behind her photography. What does this phrase suggest to you? Can you see evidence of this combination of seriousness and hope in her images? Is it possible to identify specific aspects - subjects, gestures, interactions, relationships, expressions, colours, and so on - that might be considered more (or less) serious or hopeful? Are black and white photographs more serious and/or less hopeful than colour images?

- How would you describe the relationship between figures and landscapes in these photographs?

- The title of this series of photographs is quite complex. What does it suggest to you? What types of ritual are presented in the pictures? What or who is both appearing and disappearing?

- When a person's face is concealed (or part-concealed) within a photograph, what possibilities (or problems) can arise for the viewer? Does this concealment have the potential to provoke more (or less) intrigue, mystery, empathy or emotion?

- How and where would you choose to represent yourself through photography? If you had to choose someone else to stand-in as a representation of you, who would you choose and why?

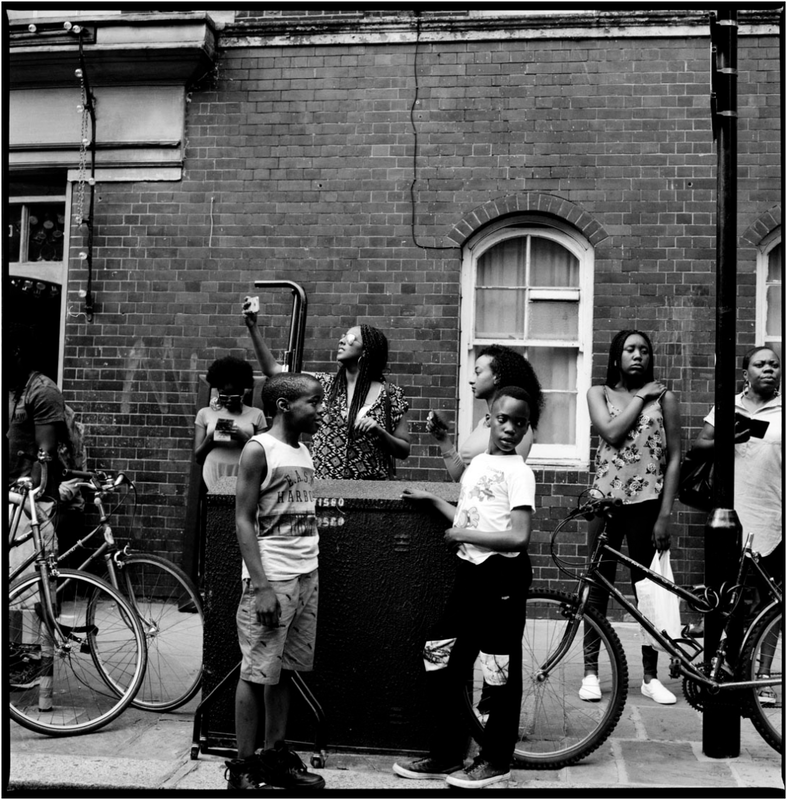

Adama Jalloh: Process

Jalloh describes her photographs as ways to keep memories alive. She grew up in south London and makes photographs on the street. She explores cultural traditions, religious beliefs, clothes and hair styles, sensitively drawing attention to intimate moments and relationships. Jalloh appreciates her local environment, documenting the lives of ordinary citizens, creating (over time) a rich archive of everyday interactions. These images are a way to create a collective memory bank of moments, a love story about belonging, charisma, survival and joy in the city. Jalloh's photographic memories belong to the whole community. It's important for her to bond with her subjects. Jalloh is an insider (to borrow Abigail Solomon-Godeau's term), a trusted witness rather than a cultural tourist. She collaborates with her subjects, allowing them to present version of themselves to her camera without judgement.

Street photography has trained my eyes and my ears [...] even if I haven't seen something, if I hear it that's when I'm preparing to take a shot [...] it's interesting how my body reacts to certain things, how alert I am

-- Adama Jalloh

For discussion:

- Jalloh uses the word "intimacy" a lot to describe the quality of her images. In what ways are her photographs intimate? What other qualities do they have?

- How reliable are photographs in conveying the experience of a photographer in a particular moment? Can photographs evoke particular - or new - sensations, sounds, smells, tastes, emotions or anxieties?

- How does photography help to develop our understanding and appreciation of places and people, known and unknown?

- What kind of person comes to mind when you think of a street photographer? How does Jalloh challenge/confirm this stereotype?

- What skills or personal qualities do you need to be a street photographer? How might these skills vary when in different cities, countries or cultures?

- What (if anything) distinguishes a 'street photograph' from other images taken in the street, such as a photograph of a building, or a person posing for camera?

- Why do you think the majority of Jalloh's images are black and white? What are the advantages or disadvantages of photographing in black and white?

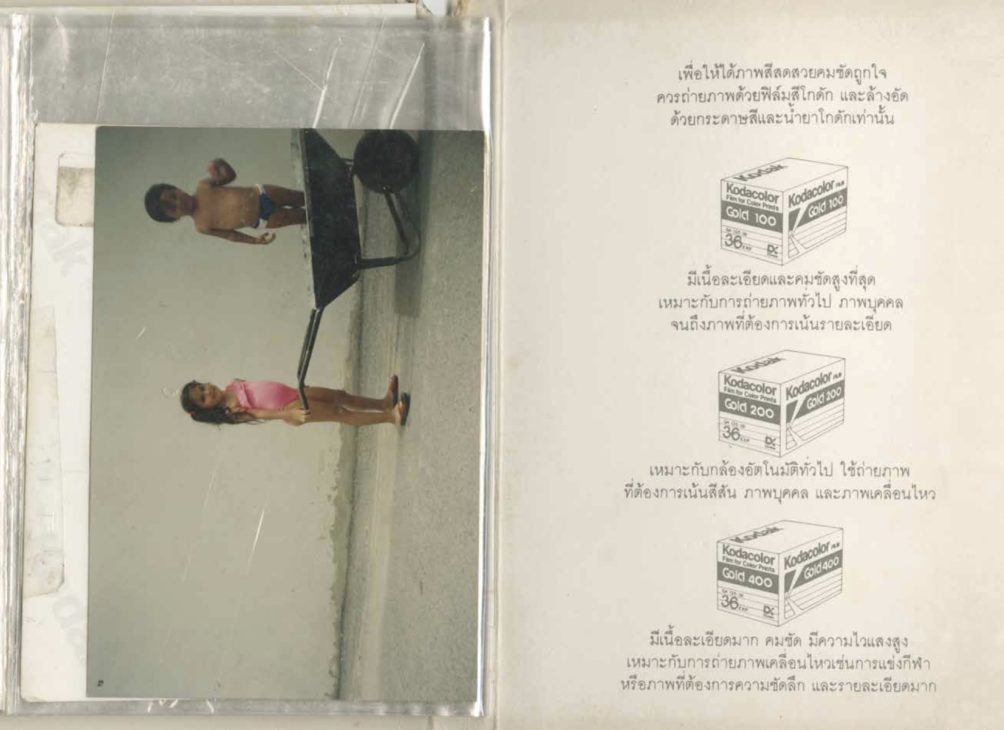

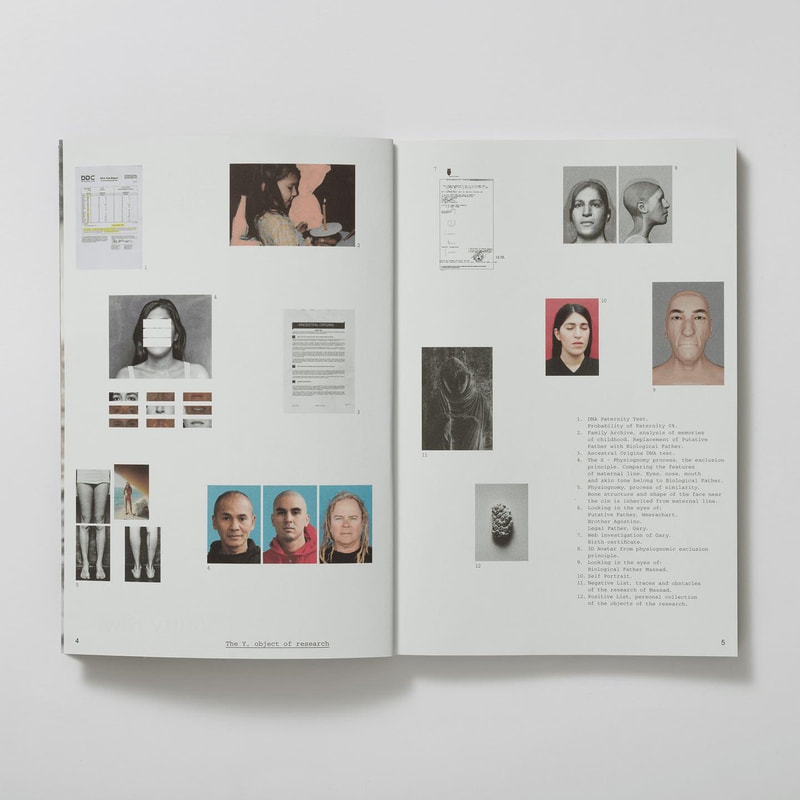

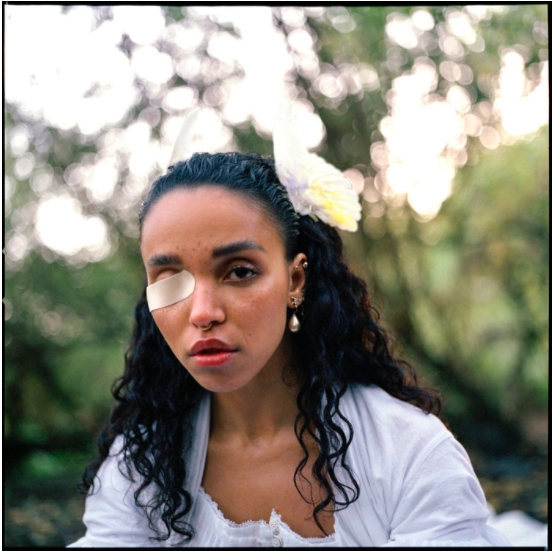

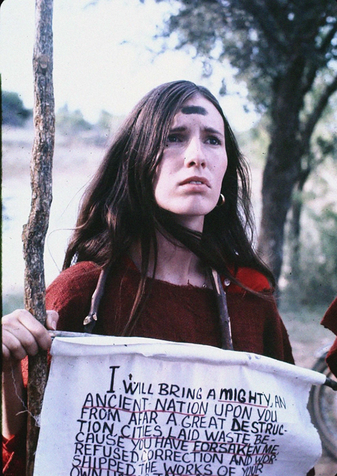

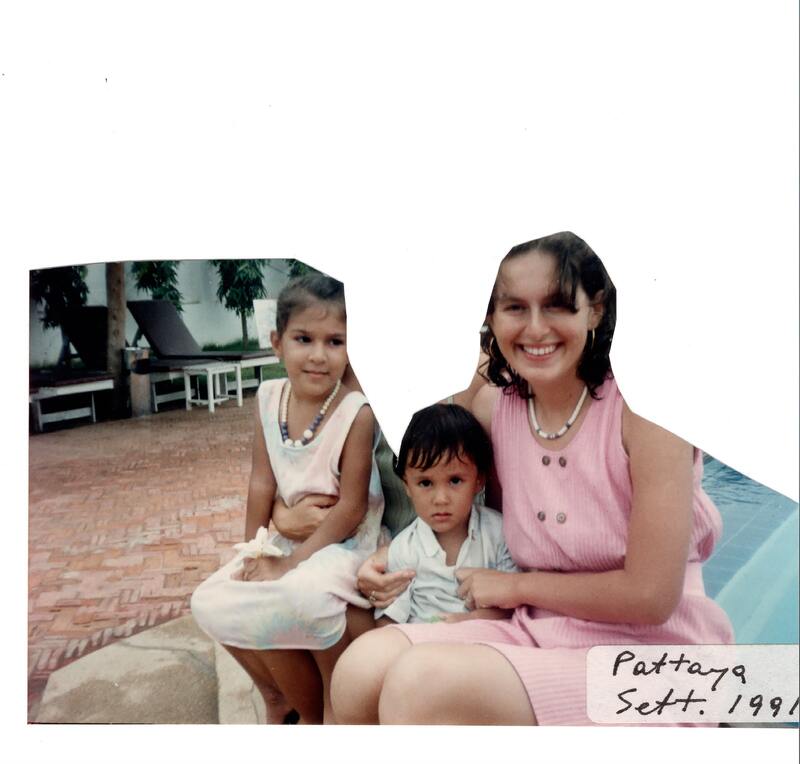

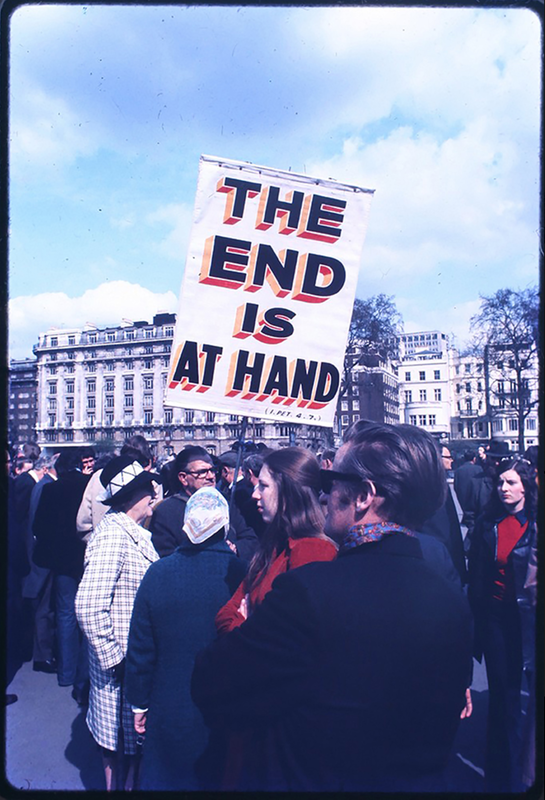

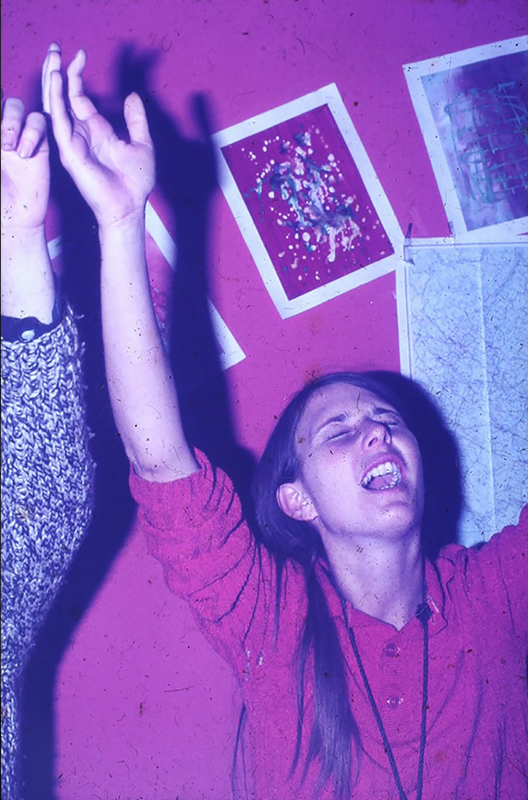

Alba Zari: OccultZari was born in Bangkok and has studied in Italy and the USA. Her current project 'Occult' tells the story of The Children of God, originally a hippy cult from the California of the late 1960s which has now spread across the world. The cult believes in 'free love' but this includes instances of the sexual abuse of children, incest and prostitution. Zari's grandmother and mother were both members and she was born into the cult. Her research has taken place in London but she intends to travel to shoot the images in Berlin, India and Thailand. The work draws on her family archive, propagandist comics, texts and videos, and archive images of other members of the sect taken from the internet. Zari assembles fragments of text and images, clues to a larger narrative. She investigates the cult's propaganda machine, contrasting the public image of belonging, joy and faith with the story of one family's troubling experiences. She also draws attention to the fate of other women and children outside her own family. Zari reveals the capacity of photographs to tell lies but how they can also be made to reveal the truth. The combination of text and image is central to the work.

I don’t think about photography as a “I have a camera; I will shoot some pictures because…”. Sometimes I see someone that looks interesting and think “I’d like to take some pictures of them” but I don’t bring my camera with me. I think photography is like a story, a concept, so if I find an interesting story I write and research before shooting it. |

For discussion:

- Zari's practice is rooted in both personal experience and research. What are the potential problems, advantages or disadvantages of this combination? How objective - not influenced by personal feelings or opinions - should (or can) research be?

- How does Zari combine archival material with images she shoots herself? What kinds of stories does she tell? Which of her images, above, might you consider the most reliable or truthful? What words help to explain some of the differences between these images and approaches?

- How would you describe Zari's attitude to the medium of photography?

- How accessible - easy to understand or connect with - are these selected images, above? How does encountering them as a collection influence your understanding or experience? Do they appear fragmented, like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle? How might the sequence, scale or context in which you encounter them alter your interpretation? (Note: the images above have been selected from available online resources and organised here by PhotoPedagogy rather than the artist).

Threshold Concepts

Threshold Concepts are the BIG IDEAS that will help students develop a deeper understanding of photography. They are not meant to be instantly understood. Once opened, they introduce students to troublesome knowledge; a new way of seeing the subject they are studying.

The work in these five exhibitions raises important questions about photography. The following Threshold Concepts - ideas that act as a gateway to exploring the subject - might be useful in helping you consider underlying themes and issues.

|

The meanings of photographs are never fixed, are not contained solely within the photographs themselves and rely on a combination of the viewer's sensitivity, knowledge and understanding, and the specific context in which the image is seen.

|

Photographs are not neutral; they are susceptible to the abuse of power. Photographs communicate powerful ideas about the world. They can be used to promote both good and bad attitudes. Therefore, students of photography must be very careful to think hard about what they see in other people's photographs and how they make their own.

|

Some suggested activities:

NOTE: The activities within this resource are designed to be accessible for all and therefore can (mostly) be completed with basic art materials and a digital camera.

- Gather, review and research a selection of photographs that are meaningful to you. They could be pictures you admire, pictures from a family album, photographs of friends, favourite images you have made and look at regularly. What stories do they tell about you, directly or indirectly? How might you make this collection more - or less - truthful or peculiar? How might you present these in a playful or profound way, for example, using various scales; concealing or revealing aspects; adding accompanying texts? How might you share these pictures with others - a slideshow, a film, an exhibition or a zine/book, for example?

- What would you like to understand better (and how might photography help you to do this)? Make a list of topics/issues that you find mysterious, troubling, urgent ... but which you know little about. Do some research and make a dossier of your discoveries. Once you have amassed some information in various forms (photocopies, notes, lists, links to videos, printed images etc.) try to make some photographs of your own. You may decide to stage these images, filling in the gaps and inventing scenarios that don't already exist. Alternatively (or additionally), you might attempt to document aspects of the story, capturing evidence of the issue you have researched in the real world.

- Experiment with making a series of self-portraits in which you don't always personally appear. Look again at the work of Widline Cadet. She sometimes uses friends and family members to stand in for her. You could try this too. But how else might you represent yourself? Consider using objects (props), settings (backdrops), lighting, costumes and other theatrical devices to present a (fictional) version of you. You might wish to experiment with old photographs of you as a child, manipulating, disrupting and/or re-presenting them in some way. How can you convey a sense of who you are without relying on a conventional self-portrait?

- How might you represent the best aspects of the community you belong to - or even set out to develop a stronger sense of community via photography? Imagine you were the official photographer of your street, neighbourhood, town or city. You have been commissioned to create a sequence of photographs celebrating the spirit of this place and its people. These images will be published in various forms - in a free newspaper, on posters in bus shelters, on postcards, on advertising hoardings etc. You are limited to 10 pictures in total. Make a larger body of images, then edit these down to just 10. Arrange in a sequence or collage. What story do they tell? What are the challenges of an activity such as this and how might you set out to overcome these?

- Re-tell in photographs a story or scene remembered from your childhood. Adama Jalloh sometimes finds scenes in her everyday life that remind her of her childhood. You may be able to do something similar, perhaps revisiting childhood locations that are meaningful to you. Alternatively, you could re-enact through staging (collaborating with relatives or friends) a childhood memory. You might even take part in this yourself, directing (rather than taking) the photograph. You could experiment with using different types of text as captions or accompanying information. You might choose to revisit a street, park or area of personal significance, or perhaps reconnect with an old friend or family member.

- Stage a collaborative pop-up exhibition. How might you team up with classmates, friends or even family members to present a group show? What shared or distinct ideas might you bring together? Where might be an appropriate - or unexpected - place to exhibit your collective efforts? Rather than worrying about expensive framing or gallery-like spaces, consider easily accessed environments and existing resources, such as displaying within classroom or corridor spaces or floors, or upon outside walls, fences, benches or washing lines. Beyond working as artists and photographers to prepare, what other skills and roles might you need to embrace? How might your exhibition be a force for good, or positive change or connections, within or beyond your group of friends, family, school or community?

Suggested Resources:

Additional Links:

Sugar Paper Theories

If you are interested in contemporary, research-led photography practice, this RPS exhibition and Photopedagogy resource is highly recommended. Jack Latham is a contemporary photographer who produces original imagery and utilises existing work to tell complex stories. Sugar Paper Theories was developed in response to a notorious unresolved double murder investigation in Iceland. The resulting photobook and exhibition is an innovative combination of original and archive images and text.

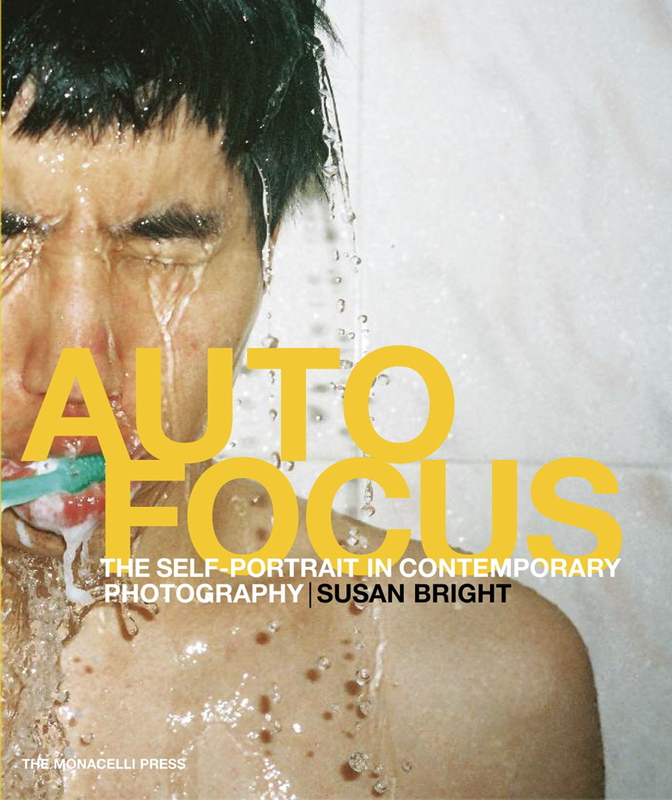

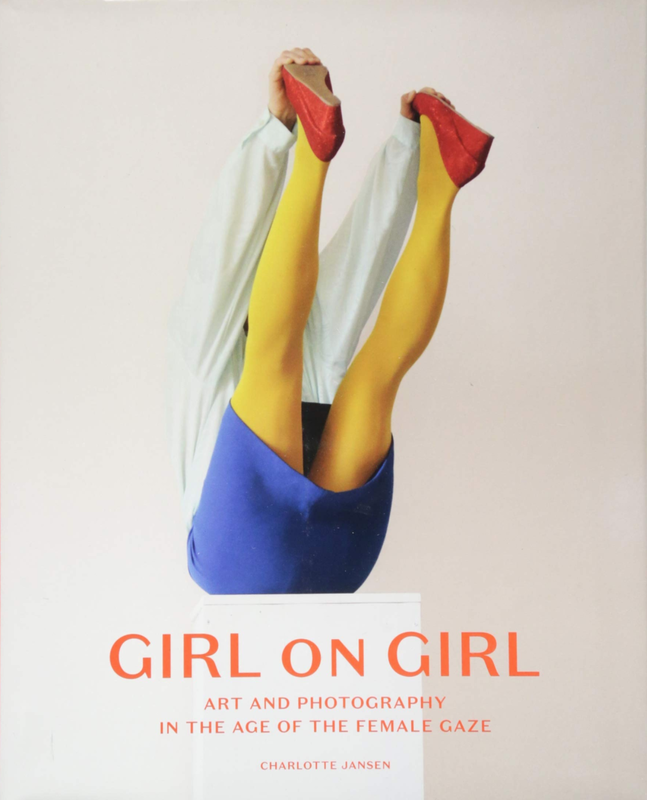

The Selfie

Widline Cadet's 'Seremoni Disparisyon (Ritual [Dis]Appearance)' is a series of self-portraits, sometimes featuring Cadet but also using friends and family. This Photopedagogy resource, 'The Selfie', takes an in-depth look at the history of self-portraiture in photography. It also includes a multitude of practical lesson ideas alongside diverse contemporary examples.

The Photograph as Evidence

How reliable are photographs as (re)sources of evidence, truth and experience? This Photopedagogy resource delves deeper. It's a fitting question to ask within an exhibition that celebrates diverse approaches united by themes of research and encounter.

If you are interested in contemporary, research-led photography practice, this RPS exhibition and Photopedagogy resource is highly recommended. Jack Latham is a contemporary photographer who produces original imagery and utilises existing work to tell complex stories. Sugar Paper Theories was developed in response to a notorious unresolved double murder investigation in Iceland. The resulting photobook and exhibition is an innovative combination of original and archive images and text.

The Selfie

Widline Cadet's 'Seremoni Disparisyon (Ritual [Dis]Appearance)' is a series of self-portraits, sometimes featuring Cadet but also using friends and family. This Photopedagogy resource, 'The Selfie', takes an in-depth look at the history of self-portraiture in photography. It also includes a multitude of practical lesson ideas alongside diverse contemporary examples.

The Photograph as Evidence

How reliable are photographs as (re)sources of evidence, truth and experience? This Photopedagogy resource delves deeper. It's a fitting question to ask within an exhibition that celebrates diverse approaches united by themes of research and encounter.