Post 16 lesson plan:

What happens when we respond to and make photographs with all of our senses?

From Jon Nicholls, Thomas Tallis School

I am very much in my body when I am creating these installations. I can feel there is a certain tension that needs to be there, a rhythm that I’m looking for.

-- Nico Krijno

This project is speculative. It touches on issues that are not yet fully formed in my own mind and is a way for me to work through some challenging (and sometimes uncomfortable) ideas and processes. I've often asserted that photography literacy involves more than just a critical or intellectual capacity - thinking in words. I believe strongly in a kind of visual literacy that does not necessarily involve using words. I'm sure we've all encountered a photograph that we respond to immediately (either positively or negatively) without being able to explain why in words until later, sometimes much later or never. All images can have this effect (affect) on us but photography's apparent relationship to visible reality means that it has a special, seductive power. It draws us in, through our eyes initially. Some photographers have been interested in appealing to the viewer's other senses - touch, smell, taste, hearing. What happens when we respond to and make photographs with all of our senses?

Take a look at this photograph by Torbjørn Rødland:

Take a look at this photograph by Torbjørn Rødland:

Spend some time with this image. As well as looking at it, try to be aware of how you respond to it with your other senses.

Some questions:

- Other than sight, which of your other senses was activated most powerfully by this image?

- What is it about the photograph that affected you?

- If you were to make a new photograph in response to this image, what would you do?

Photographs have an impact on us that is not solely based on seeing. And I argue that we need another approach to understanding photographs, other than simply looking at them. Listening to Images challenges us to move from vision to sound by way of touch. There is no question that images move us. But the question is, how does that happen? Photographs touch us emotionally, but also in a tactile sense through our physical encounters with them. That moment of contact is about a particular level of frequency, or resonance. But to make contact, you have to attune yourself to certain frequencies of encounter that aren’t always available to us in our normal register.

-- Tina M. Campt

More than simply looking

In her book 'Listening to Images', Tina M. Campt argues that photographs, specifically those made for identification purposes, can speak to us. She begins with a memory about her father's grief-stricken quiet hum before developing a counter-intuitive method for listening to the sounds of quiet images. "Sound," she claims, "need not be heard to be perceived. Sound can be listened to, and, in equally powerful ways, sound can be felt; it both touches and moves people." At very low frequencies sound is felt rather than heard. By listening carefully to images of apparent subjugation she becomes aware of their quiet resistance.

Listening requires an attunement to sonic frequencies of affect and impact. It is an ensemble of seeing, feeling, being affected, contacted, and moved beyond the distance of sight and observer. She refers to the need for a "haptic" sensibility - the desire to grasp something - that connects us with the "event" of the photograph. She refers to four archives of images of black diaspora: passport photos of black British men in postwar Birmingham; late nineteenth-century ethnographic photos of rural Africans in the Eastern Cape and early twentieth-century studio portraits of African Christians in South African urban centres; and convict photographs taken between 1893 and 1904 of inmates at Breakwater Prison in Cape Town. Through careful listening, Campt hears the "softly buzzing tension of colonialism, the low hum of resistance and subversion, and the anticipation and performance of a future that has yet to happen." (Duke University Press)

|

|

The book cover uses a set of images from the Gulu Real Art Studio. The complex chain of events leading to the exhibition of these portraits with faces missing provides a fascinating example of the ways in which the meanings of photographs change over time.

Some questions:

- What might draw us to (or repel us from) a particular photograph?

- How do photographs affect us emotionally? How does it feel to be moved by an image?

- How might we listen to photographs? What can we hope to hear?

- How do we engage sensitively with photographs made by agencies of the state (e.g. identification pictures) from the point of view of the sitter?

- How might we differentiate a quiet from a noisy image?

- How can we engage our non-visual senses in responding to photographic images?

- What might it mean to watch, rather than see, a photographic image? How do we continually negotiate the meaning of a photograph?

Scratch and Sniff

Some contemporary light and lens based artists have become fascinated by the materials and processes of photography. This may be a reaction to the relative immateraility of digital images. Nevertheless, these artists have explored the various combinations of photographic materials and chemistry in an attempt to reconnect with the origins of the medium and the magic of photographic imagery. Alongside this there has been a renewed desire to reconnect with the landscape and particular processes that connect photography to nature: light, exposure, growth, decay etc. Here are several artists whose work explores some of these issues. I have chosen them because they make work which also appeals to one or more of the non-visual senses.

Odette England - Scratch

Odette England's series Thrice Upon a Time explores notions of loss, time and home through a kind of photo performance. having been forced to abandon the farm land in which she grew up, England asked her parents to tie photographic negatives to the soles of their shoes as they re-visited her childhood farm and the locations where they had made snapshots of her as a child. The damaged negatives, containing traces of the land which they depict, were then pieced back together and re-printed to reveal these abrasions. The prints contain many kinds of traces both physical and emotional. They evoke the rough texture of the farmland, record the friction between boots and land and suggest the troubled nature of childhood memories since we can never really recover the exact texture of these places and stories, even with the aid of photography.

Jane Fulton Alt - Sniff

|

The Burn, by photographer Jane Fulton Alt, is a sequence of photographs of smouldering controlled forests fires. The video footage reveals a strange combination of calm prairie management techniques and rapacious fire sweeping across the landscape.

Fulton Alt's photographs tend to concentrate on the billowing smoke that appears after the fire has subsided. The images are uncanny, showing us a barely recognisable landscape, and my response when I first encountered them was the imaginary smell of suffocating wood smoke. This was partly caused by the compressed space in the pictures conveying a sense of enclosure in which we can only make out the objects nearest to us, the distant landscape shrouded in smoke. But the pictures also prompted memories of childhood bonfires when the wind suddenly changes direction and lungs are momentarily filled with acrid, smoke-filled air. |

|

Keith Arnatt's Pictures from a Rubbish Tip are also worth exploring in the context of smelly photographs.

Taste Tests

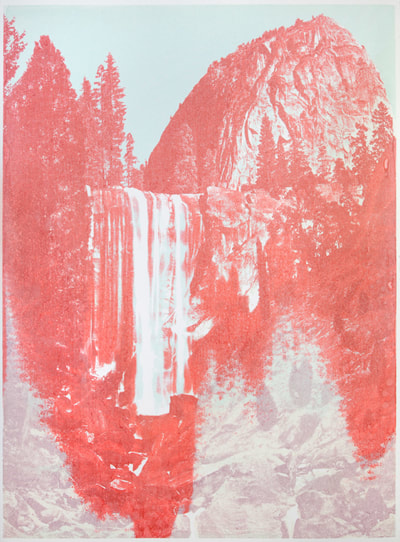

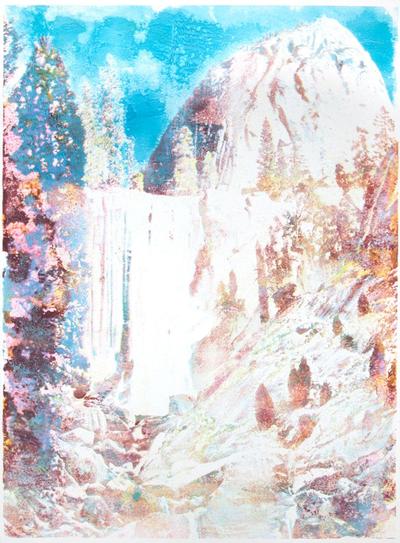

There are plenty of photographs of food. Some of them are effective in communicating a sense of taste but, in my view, none are as powerful as Matthew Brandt's Taste Tests. Brandt has made a name for himself by pushing at the limits of photographic legibility through the use of unusual materials and processes. He has used everything from bees to lake water to create his images. In this series, however, he employs a wide range of food items, from Cheez Wizz to Kool Aid, to create the 'ink' with which to screen print photographs of iconic American landscapes. The resulting pictures often have the look of a sweet shop with a bright, glossy, non-naturalistic, even garish, colour palette. Their sweetness is partly attractive in a childlike way but we are also slightly repulsed by the artificial, sugary surfaces of these confections. Brandt He uses both the RGB and CMYK colour models to make the prints and reminds us that the digital images we consume are as artificial as sweets.

Some suggested activities:

- Take a careful look at the work of Torbjørn Rødland. Print out one or more of his photographs. Re-photograph them to further emphasise their relationship to the sense of touch. For example, you may want to include a part of your body obscuring part of Rødland's image or you may want to work with an additional texture by pasting the image onto a rough surface, submersing it in water or cracking an egg onto it.

- Select a small sample of photographic portraits from an image archive like that on the Autograph ABP website or these photographs from late 19th century Japan. Following Tina M. Campt's advice, listen carefully to the pictures. Remember, this isn't about the pictures making an audible noise, but rather you being super sensitive to the vibrations and frequencies you may be able to detect. It's about becoming aware of the energies in the photograph that might exist beneath the surface we see with our eyes. Pay very close attention. Lean in. What can you 'hear'?

- Select either the sense of touch, hearing, smell or taste. Create a sequence of photographic images exploring your chosen sense. Think carefully about how both the subjects of your pictures and the ways in which they are presented to the viewer can contribute to stimulating the appropriate sensory response.