Posing Problems for Photographic Portraiture

By Graham Hooper

Part One: Traditional Challenges

For teachers of photography, portraiture can be a minefield. Young people subjected to (and enamoured by) pouting girls on Instagram or high-glamour fashion shoots in Vogue come to the genre with high expectations. Those aspirations can so easily and so often lead to disappointing outcomes; aesthetically certainly, which can sadly translate into low attainment too. The damage then done to the students’ self-esteem can be sudden, deep and long-lasting. Whilst our role is to encourage and support students in their desire to make imagery that they find meaningful and relevant, we must also achieve academic success. There is always that balance to be had.

Attempting to record with a camera more than meets the eye is a creative pursuit that connects the earliest photographers with the most contemporary. The problem of portraiture specifically, from the ethical through to the most practical, would discourage many a self-reflective camera-user. That said, the rewards for success can far outweigh the inherent obstacles, and can make for deeply moving and profound images. The flurry of recent high profile and popular exhibitions in the Capital attests to that, and reflects a continued interest in the subject for photographers and their audiences alike. The Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize (at The National Portrait Gallery) annually selects from and celebrates the form in contemporary practice, with images that operate at the very edges of the field.

I take a lot of photographs, but very few of the pictures I take are of people. Even as a father of three I have only a handful of photographs of my own family, which is quite unusual I think. My wife does the job of documenting our family life in pictures and proceeds to post to Facebook on occasions. I’d bet that most photographs taken by most camera-owners are of people though, and especially of faces. Most of those, I’d imagine, are the faces of family and friends. It’s natural to want to look at other people. Photographers are people after all; we are people surrounded by other people. People change over time, certainly physically and it’s a natural response then to feel compelled to use our cameras to make records, for posterity, of the people we live with and care about. We take photographs of people to help us remember why special events are special - the weddings, the birthdays and holidays - these are shared celebrations, and rites of passage. In our family there’s the annual formality of the framed school pose, for others selfies have become a key function of the smart phone, and one utilised more than daily.

According to the photographer Inge Monath, a successful portrait "catches a moment of stillness within the daily flows of things, when the inside of a person has a chance to come through" and furthermore that, "Character revelation is the essence of good portraiture”. She is quoted in the opening paragraphs of Graham Clarke’s seminal text on The Photograph. In the chapter on The Portrait in Photography he goes on to discuss the tensions between showing a person and revealing them; is either ever fully possible, or indeed are both actually inevitable? What is known about a person might differ from what is expressed. All this, and more, forms part of the ‘problem’ of portraiture, and identity in photography more generally. That is not to say a ‘solution’ shouldn’t be sought. I’d go as far as to say the best photographs are often the most difficult to realise, and this can be the case with pictures of people.

The lineage of the portrait begins with the portrait painting, surviving best perhaps as commissions of the rich and powerful, often depicting as well as a visual ‘likeness’, admiration or affection, or an attempt to achieve a kind of immortality. The role and purpose of the portrait in history actually is diverse and complex. The photographic portrait builds on and extends much of these traditions and functions, but also explores the values and conventions that come with the territory itself. Now the world is awash with portraits. The paparazzi give us a stream of celebrity ‘pics’, our lives are flooded with images of ‘beautiful’ people. But most people aren’t famous and we don’t necessarily think of our family snapshots as portraits. But there is something about people and their faces that can make us attend and respond in ways that images of objects and landscapes might fail to achieve, in quite the same way or to the same extent.

The difficulty of making pictures of people, ones that we might consider to have acquired the status of portraiture, might not be evident in the images that hang in a gallery, as the process is hidden in the preparation. Looking at portraits as I have a lot recently, it seems as though good portraits are often successful because they manage to somehow achieve that elusive balance of describing and explaining, simultaneously and effortlessly. They reveal enough to satisfactorily reveal, but leave enough hidden to intrigue us. They can become great portraits when and if they also manage to reflect something both of the sitter and the photographer themselves, and the relationship between them. That is easier said than done. The best manage to be both specific and universal, giving the viewer the sensation of being observer and observed. But these attributes are aspirational for most of us, when just describing fully, accurately and sensitively, can in itself be enough of a task.

People and faces will fill my Instagram feed this year. As a challenge to myself, I have committed to using my camera to observe and record them exclusively. My images will not be of famous people in far-flung locations selling life-styles, or of young women pouting, and I want to avoid the ‘shortcuts’ of using camera blur or dark, partially-obscured bodies to ‘avoid’ the problems that are as much practical as ethical. I want to try and photograph faces fully, pure and simple. Is that possible though? Photographing people, I am forever telling my students, is probably one of the hardest things to succeed at doing. But that does nothing to dampen their desire to point their cameras at faces, and (I am fully aware) might even encourage them. Those students that persist in their attempts, despite my perseverance in distracting them, are determined and focussed – two attributes that are essential to all photographers, but especially for the portrait photographer I think.

The first obstacle we often encounter when approaching the challenge of pointing our camera at a face is as simple as it is significant: in my experience most people just don’t want to be photographed. They become self-conscious, overly aware of themselves and how they look, and they don’t want that captured for eternity, let alone have their visual identity shared on social-media. Either that, or they become unexpectedly theatrical, suddenly uninhibited, and begin perform to camera. Both responses are behaviours we perhaps didn’t want and were hoping to avoid when we imagined our poignant and candid close-up shot. The exhibition at Tate Modern, Performing for the Camera (18 February – 12 June 2016), centres on this very idea – it’s not necessarily a bad thing!

But who should photographers photograph? That is the next question, and one that I put to them when they tell me that photographing people is what they really, really, really want to do, more than anything in the whole world. Self-portraiture certainly side-steps one of the basic dilemmas, of who to photograph. When photographing myself, for instance, I can refrain from pouting (hopefully) and decide on just the right level of self-awareness I want to suggest in the image. Selfies have a long and fine tradition. Lee Friedlander, the American photographer, who re-defined the genre in his 1970 book simply called Self-portraits, alludes to his visual presence whilst rarely fully depicting it. Instead there are shadows and reflections. Cindy Sherman, another significant American self-portraitist, at that time and since, took a different tack, and created images of herself as anyone else; film stars, housewives, models. I’d argue that these two different approaches are solutions of a sort, but they’re also a kind of bypassing of the issue.

If you’re not going to photograph yourself, then who? Students rarely actually want to make themselves the subject of their images anyway. It’s too public, it feels arrogant, or just whimsical in their eyes, and they want to make serious art.

Family then maybe? They’re accessible and let you consider relationships, gender, domesticity, all big issues to contend with. But no, they don’t want to photograph their annoying brother, or their mum and dad, annoyed or annoying. Then maybe a friend, or a neighbour? Someone they know quite well. But that too is dismissed out-of-hand. It would be embarrassing they say. Their friends wouldn’t take it seriously and, well, all those other people aren’t really interesting enough. Again they’d feel self-conscious and awkward.

I try to explain that photographing people is always a bit more challenging as a subject because you’re dealing with humans. They can turn up late and don’t always put their head at the angle you want them too. So there’s sometimes more to negotiate and contend with; you have to actually engage with the subject! You have to talk to them, and they might talk to you. There might even be a conversation, I say.

They’re not keen. It’s strangers that they’re thinking of. They think it’ll be easier. I explain that it’s not New York or the 1960’s anymore, and they’re not Garry Winogrand anyway. Street photographers like him could wander around New York, happily invading the personal body space of ‘interesting-looking’ strangers without any real concern for privacy or manners it seems. People are rightly much more sensitive to that now. Far from being flattered they’re much more likely to feel concerned about how their images might be used, and you, the photographer, suddenly become the object of suspicion, and even aggression. Either that or you have no impact on your subject and they in turn create or rather offer little visual interest. The pictures look banal, though that might just be the contemporary eye, making comparisons with street photographers of the past. Was Paris in the 1940’s equally inane to the street photographers of the day? They seem to have dressed better, looking back, with all those elegant hats! This could just be the effect of a modern mind projected on the past, or not imagining the past from the perspective of the future.

I ask them if they think some people are more interesting, or at least more interesting to look at, than other people. They like the work of Diane Arbus, who established a reputation for seeking out and documenting the outsider and the outcast; transvestites and nudists, in the travelling circus or the mental asylum. These people can look or feel different and strange. I imagine that part of the draw to this kind of subject matter is innocent curiosity, though for Arbus she identified at a deeper level with their place in the world. Whether or not they do much more than let us gawp is debateable. I wonder alongside the students, might there be more value in showing how people that could seem so very unusual in person could have the same needs, fears, desires as the rest of us. I then invite these young photographers to consider the possibility that we might all have personalities and idiosyncrasies that could be better understood if it were only for a good photographer to approach the situation with openness, honesty and commitment.

We look at some more portraits in a lesson, this time of people that aren’t so different from them; pictures of ‘ordinary’ people that they might find extra-ordinary when pictured. We look at Rineke Dijkstra’s portraits. She’s interested in observing moments of heightened psychology, during the course of which she has documented matadors fresh from the ring, and brand-new mothers holding brand-new babies. The project that involved her recording teenage swimmers on beaches is a poignant series, but the teenagers in my classroom consider them too staged. Similarly Nicholas Nixon’s “Brown Sisters”, his wife and her three sisters, who he has been photographing on the same day each year for over 4 decades. It is an impressive study of familial relations, extraordinary for its subtlety and duration. In these examples the subject is well aware of the camera. There is a contract, in some instances legal, if not at least a tacit agreement, to being scrutinised by the lens. It is a responsibility on the part of the person behind the lens that demands respect and dignity. For the subject too there might be an equal requirement and demand for a degree of patience and compliance. But there is inevitably an encounter and interaction that needs a degree of mutual understanding.

This kind of work sits halfway between the candid and the staged. I don’t think there is anything inherently dishonest or artificial about a model in a studio. It can feel as contrived or natural as any other situation and depends on those present. The photographs of Cindy Sherman, which are planned and prepared, are too conceptual for many, the focus being the underlying political content rather than the simple visual presentation. Whilst Gregory Crewdson’s intricate, grand and wholly designed photographs of people in environments, each carefully constructed and lit, are seductive and captivating, they are obviously also incredibly complex to organise logistically. It is beyond the scope of most photographers, let alone young photography students, at least on his scale.

I ask the students whether they think Tierney Gearon’s work is dramatised in anyway. She caused a furore when she photographed her children, in beautiful colour and under exquisite light, but often naked, wearing animal masks at times, and even on occasions urinating in snow. Do they think these images are genuine or controlled? They certainly blur the boundaries between fantasy and reality in my mind. The questions come thick and fast: are they real? Are they accurate? What do they actually tell us? What do they explain that is important? What do they describe that is useful? When Helen Levitt photographed kids playing in Harlem in the 40’s it all appears so easy. They are innocent – the photographer and the children. Creating that body of work would be impossible now, and Gearon’s output is almost a contemporary attempt at repeating the exercise, as well as an appreciation of the fact that the world has changed, and that the best of intentions might be doomed to fail.

I compare Gearon’s family to those photographed by Bill Owens in his ‘suburban families’ project. We can then talk about our own families. The pictures give us an opportunity and a permission to do that. They might show us a husband and wife in a kitchen, but are about marriage, happiness, kitchens, parenthood and all those other fascinating things, and all at the same time. That is when portraits are more than pictures of what people look like. But that perceptual processing is done as much by us as by the photographer. Owens has sought out these people, has created these situations, has made these pictures, but we then must do our own looking and thinking.

It leads me onto the studies by Richard Billingham, a Turner Prize winner with his book, Ray’s A Laugh, which revealed his family life, warts and all. His parents are seen doing jigsaws in their council flat, arguing, stroking a kitten, being sick. Hopefully not all activities that we recognise as typical home life but I am still keen to encourage students to observe known individuals rather than strangers, for all sorts of reasons. This time I juxtapose the Billingham images with pictures of family life by Martin Parr. It is fascinating to hear the conversation move from discussion about love and companionship to interior décor and mealtime etiquette. How many families still eat together regularly? How many still go home to a place with a mother and father? Do you do jigsaws? Do you have painted or wallpapered walls for that matter?

Eventually, looking at various examples of differing approaches to portraiture we come, inevitably perhaps, to the work of Ralph Eugene Meatyard. Humorously a photographer born in a town called Normal, he recorded his small and conservative community in very unconventional ways. The images are raw but crafted. There is still some theatricality involved but they are relaxed too. He takes the locality into account – the children and adults we come across are protagonists in a strange abandoned film set of old wooden farm outhouses. Shot at weekends, on his days off as an optician (imagine, all those lenses!), they are a fun but serious series of explorations. The folk we see are not so much posing as behaving, acting out, and not necessarily for the camera as much as for themselves or each other. There is the interaction too, the relationships, friends and neighbours, photographer and family. There are faces and bodies. The pictures, and the people in them, feel self-aware but innocent all at the same time. The black and white of the pictures feels full and deep, like the people in them. There’s all that wood grain as a backdrop, the geometry of the doorways and windows and then the strange masks and camera blur. His work gets closest to what is achievable and aspirational in student portrait photography. In photographing the local, the immediate, as viewers we are actually able to connect with what is universal and timeless.

Attempting to record with a camera more than meets the eye is a creative pursuit that connects the earliest photographers with the most contemporary. The problem of portraiture specifically, from the ethical through to the most practical, would discourage many a self-reflective camera-user. That said, the rewards for success can far outweigh the inherent obstacles, and can make for deeply moving and profound images. The flurry of recent high profile and popular exhibitions in the Capital attests to that, and reflects a continued interest in the subject for photographers and their audiences alike. The Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize (at The National Portrait Gallery) annually selects from and celebrates the form in contemporary practice, with images that operate at the very edges of the field.

I take a lot of photographs, but very few of the pictures I take are of people. Even as a father of three I have only a handful of photographs of my own family, which is quite unusual I think. My wife does the job of documenting our family life in pictures and proceeds to post to Facebook on occasions. I’d bet that most photographs taken by most camera-owners are of people though, and especially of faces. Most of those, I’d imagine, are the faces of family and friends. It’s natural to want to look at other people. Photographers are people after all; we are people surrounded by other people. People change over time, certainly physically and it’s a natural response then to feel compelled to use our cameras to make records, for posterity, of the people we live with and care about. We take photographs of people to help us remember why special events are special - the weddings, the birthdays and holidays - these are shared celebrations, and rites of passage. In our family there’s the annual formality of the framed school pose, for others selfies have become a key function of the smart phone, and one utilised more than daily.

According to the photographer Inge Monath, a successful portrait "catches a moment of stillness within the daily flows of things, when the inside of a person has a chance to come through" and furthermore that, "Character revelation is the essence of good portraiture”. She is quoted in the opening paragraphs of Graham Clarke’s seminal text on The Photograph. In the chapter on The Portrait in Photography he goes on to discuss the tensions between showing a person and revealing them; is either ever fully possible, or indeed are both actually inevitable? What is known about a person might differ from what is expressed. All this, and more, forms part of the ‘problem’ of portraiture, and identity in photography more generally. That is not to say a ‘solution’ shouldn’t be sought. I’d go as far as to say the best photographs are often the most difficult to realise, and this can be the case with pictures of people.

The lineage of the portrait begins with the portrait painting, surviving best perhaps as commissions of the rich and powerful, often depicting as well as a visual ‘likeness’, admiration or affection, or an attempt to achieve a kind of immortality. The role and purpose of the portrait in history actually is diverse and complex. The photographic portrait builds on and extends much of these traditions and functions, but also explores the values and conventions that come with the territory itself. Now the world is awash with portraits. The paparazzi give us a stream of celebrity ‘pics’, our lives are flooded with images of ‘beautiful’ people. But most people aren’t famous and we don’t necessarily think of our family snapshots as portraits. But there is something about people and their faces that can make us attend and respond in ways that images of objects and landscapes might fail to achieve, in quite the same way or to the same extent.

The difficulty of making pictures of people, ones that we might consider to have acquired the status of portraiture, might not be evident in the images that hang in a gallery, as the process is hidden in the preparation. Looking at portraits as I have a lot recently, it seems as though good portraits are often successful because they manage to somehow achieve that elusive balance of describing and explaining, simultaneously and effortlessly. They reveal enough to satisfactorily reveal, but leave enough hidden to intrigue us. They can become great portraits when and if they also manage to reflect something both of the sitter and the photographer themselves, and the relationship between them. That is easier said than done. The best manage to be both specific and universal, giving the viewer the sensation of being observer and observed. But these attributes are aspirational for most of us, when just describing fully, accurately and sensitively, can in itself be enough of a task.

People and faces will fill my Instagram feed this year. As a challenge to myself, I have committed to using my camera to observe and record them exclusively. My images will not be of famous people in far-flung locations selling life-styles, or of young women pouting, and I want to avoid the ‘shortcuts’ of using camera blur or dark, partially-obscured bodies to ‘avoid’ the problems that are as much practical as ethical. I want to try and photograph faces fully, pure and simple. Is that possible though? Photographing people, I am forever telling my students, is probably one of the hardest things to succeed at doing. But that does nothing to dampen their desire to point their cameras at faces, and (I am fully aware) might even encourage them. Those students that persist in their attempts, despite my perseverance in distracting them, are determined and focussed – two attributes that are essential to all photographers, but especially for the portrait photographer I think.

The first obstacle we often encounter when approaching the challenge of pointing our camera at a face is as simple as it is significant: in my experience most people just don’t want to be photographed. They become self-conscious, overly aware of themselves and how they look, and they don’t want that captured for eternity, let alone have their visual identity shared on social-media. Either that, or they become unexpectedly theatrical, suddenly uninhibited, and begin perform to camera. Both responses are behaviours we perhaps didn’t want and were hoping to avoid when we imagined our poignant and candid close-up shot. The exhibition at Tate Modern, Performing for the Camera (18 February – 12 June 2016), centres on this very idea – it’s not necessarily a bad thing!

But who should photographers photograph? That is the next question, and one that I put to them when they tell me that photographing people is what they really, really, really want to do, more than anything in the whole world. Self-portraiture certainly side-steps one of the basic dilemmas, of who to photograph. When photographing myself, for instance, I can refrain from pouting (hopefully) and decide on just the right level of self-awareness I want to suggest in the image. Selfies have a long and fine tradition. Lee Friedlander, the American photographer, who re-defined the genre in his 1970 book simply called Self-portraits, alludes to his visual presence whilst rarely fully depicting it. Instead there are shadows and reflections. Cindy Sherman, another significant American self-portraitist, at that time and since, took a different tack, and created images of herself as anyone else; film stars, housewives, models. I’d argue that these two different approaches are solutions of a sort, but they’re also a kind of bypassing of the issue.

If you’re not going to photograph yourself, then who? Students rarely actually want to make themselves the subject of their images anyway. It’s too public, it feels arrogant, or just whimsical in their eyes, and they want to make serious art.

Family then maybe? They’re accessible and let you consider relationships, gender, domesticity, all big issues to contend with. But no, they don’t want to photograph their annoying brother, or their mum and dad, annoyed or annoying. Then maybe a friend, or a neighbour? Someone they know quite well. But that too is dismissed out-of-hand. It would be embarrassing they say. Their friends wouldn’t take it seriously and, well, all those other people aren’t really interesting enough. Again they’d feel self-conscious and awkward.

I try to explain that photographing people is always a bit more challenging as a subject because you’re dealing with humans. They can turn up late and don’t always put their head at the angle you want them too. So there’s sometimes more to negotiate and contend with; you have to actually engage with the subject! You have to talk to them, and they might talk to you. There might even be a conversation, I say.

They’re not keen. It’s strangers that they’re thinking of. They think it’ll be easier. I explain that it’s not New York or the 1960’s anymore, and they’re not Garry Winogrand anyway. Street photographers like him could wander around New York, happily invading the personal body space of ‘interesting-looking’ strangers without any real concern for privacy or manners it seems. People are rightly much more sensitive to that now. Far from being flattered they’re much more likely to feel concerned about how their images might be used, and you, the photographer, suddenly become the object of suspicion, and even aggression. Either that or you have no impact on your subject and they in turn create or rather offer little visual interest. The pictures look banal, though that might just be the contemporary eye, making comparisons with street photographers of the past. Was Paris in the 1940’s equally inane to the street photographers of the day? They seem to have dressed better, looking back, with all those elegant hats! This could just be the effect of a modern mind projected on the past, or not imagining the past from the perspective of the future.

I ask them if they think some people are more interesting, or at least more interesting to look at, than other people. They like the work of Diane Arbus, who established a reputation for seeking out and documenting the outsider and the outcast; transvestites and nudists, in the travelling circus or the mental asylum. These people can look or feel different and strange. I imagine that part of the draw to this kind of subject matter is innocent curiosity, though for Arbus she identified at a deeper level with their place in the world. Whether or not they do much more than let us gawp is debateable. I wonder alongside the students, might there be more value in showing how people that could seem so very unusual in person could have the same needs, fears, desires as the rest of us. I then invite these young photographers to consider the possibility that we might all have personalities and idiosyncrasies that could be better understood if it were only for a good photographer to approach the situation with openness, honesty and commitment.

We look at some more portraits in a lesson, this time of people that aren’t so different from them; pictures of ‘ordinary’ people that they might find extra-ordinary when pictured. We look at Rineke Dijkstra’s portraits. She’s interested in observing moments of heightened psychology, during the course of which she has documented matadors fresh from the ring, and brand-new mothers holding brand-new babies. The project that involved her recording teenage swimmers on beaches is a poignant series, but the teenagers in my classroom consider them too staged. Similarly Nicholas Nixon’s “Brown Sisters”, his wife and her three sisters, who he has been photographing on the same day each year for over 4 decades. It is an impressive study of familial relations, extraordinary for its subtlety and duration. In these examples the subject is well aware of the camera. There is a contract, in some instances legal, if not at least a tacit agreement, to being scrutinised by the lens. It is a responsibility on the part of the person behind the lens that demands respect and dignity. For the subject too there might be an equal requirement and demand for a degree of patience and compliance. But there is inevitably an encounter and interaction that needs a degree of mutual understanding.

This kind of work sits halfway between the candid and the staged. I don’t think there is anything inherently dishonest or artificial about a model in a studio. It can feel as contrived or natural as any other situation and depends on those present. The photographs of Cindy Sherman, which are planned and prepared, are too conceptual for many, the focus being the underlying political content rather than the simple visual presentation. Whilst Gregory Crewdson’s intricate, grand and wholly designed photographs of people in environments, each carefully constructed and lit, are seductive and captivating, they are obviously also incredibly complex to organise logistically. It is beyond the scope of most photographers, let alone young photography students, at least on his scale.

I ask the students whether they think Tierney Gearon’s work is dramatised in anyway. She caused a furore when she photographed her children, in beautiful colour and under exquisite light, but often naked, wearing animal masks at times, and even on occasions urinating in snow. Do they think these images are genuine or controlled? They certainly blur the boundaries between fantasy and reality in my mind. The questions come thick and fast: are they real? Are they accurate? What do they actually tell us? What do they explain that is important? What do they describe that is useful? When Helen Levitt photographed kids playing in Harlem in the 40’s it all appears so easy. They are innocent – the photographer and the children. Creating that body of work would be impossible now, and Gearon’s output is almost a contemporary attempt at repeating the exercise, as well as an appreciation of the fact that the world has changed, and that the best of intentions might be doomed to fail.

I compare Gearon’s family to those photographed by Bill Owens in his ‘suburban families’ project. We can then talk about our own families. The pictures give us an opportunity and a permission to do that. They might show us a husband and wife in a kitchen, but are about marriage, happiness, kitchens, parenthood and all those other fascinating things, and all at the same time. That is when portraits are more than pictures of what people look like. But that perceptual processing is done as much by us as by the photographer. Owens has sought out these people, has created these situations, has made these pictures, but we then must do our own looking and thinking.

It leads me onto the studies by Richard Billingham, a Turner Prize winner with his book, Ray’s A Laugh, which revealed his family life, warts and all. His parents are seen doing jigsaws in their council flat, arguing, stroking a kitten, being sick. Hopefully not all activities that we recognise as typical home life but I am still keen to encourage students to observe known individuals rather than strangers, for all sorts of reasons. This time I juxtapose the Billingham images with pictures of family life by Martin Parr. It is fascinating to hear the conversation move from discussion about love and companionship to interior décor and mealtime etiquette. How many families still eat together regularly? How many still go home to a place with a mother and father? Do you do jigsaws? Do you have painted or wallpapered walls for that matter?

Eventually, looking at various examples of differing approaches to portraiture we come, inevitably perhaps, to the work of Ralph Eugene Meatyard. Humorously a photographer born in a town called Normal, he recorded his small and conservative community in very unconventional ways. The images are raw but crafted. There is still some theatricality involved but they are relaxed too. He takes the locality into account – the children and adults we come across are protagonists in a strange abandoned film set of old wooden farm outhouses. Shot at weekends, on his days off as an optician (imagine, all those lenses!), they are a fun but serious series of explorations. The folk we see are not so much posing as behaving, acting out, and not necessarily for the camera as much as for themselves or each other. There is the interaction too, the relationships, friends and neighbours, photographer and family. There are faces and bodies. The pictures, and the people in them, feel self-aware but innocent all at the same time. The black and white of the pictures feels full and deep, like the people in them. There’s all that wood grain as a backdrop, the geometry of the doorways and windows and then the strange masks and camera blur. His work gets closest to what is achievable and aspirational in student portrait photography. In photographing the local, the immediate, as viewers we are actually able to connect with what is universal and timeless.

Part Two: Challenging Traditions

Despite all the reasons for not approaching portraiture, and as we have seen there are numerous, there are simple ways to engage meaningfully with the genre. I have found this out through making my own attempts, by studying the work of other photographers (I name just a few in part one) but especially by working alongside students. They often surprise me with their audacity and ingenuity. Certainly, it is by actually trying to work through problems that solutions are best arrived at, rather than just writing them off, in the mind or in theory.

The images discussed in this part represent a variety of approaches, categorised for convenience, that might help others to recognise the strategy being employed by a student and so support their work, or offer other routes in. I am sure there are others but these seem to be the most popular and effective with the time, money and resources most often available to the average 16 to 19 year old.

Cropping (and juxtaposition)

The most effective of all the techniques in the photographer’s tool kit is central to how this image works. The top and the bottom of the field of view have been sliced away. The result is abstracted, so we are able to recognise the person in the picture, but it is their presence of a human, clothed and colourful, that carries the meaning rather than the image of any one, single person in particular. The anonymity here is not for privacies sake but rather to de-personalise so as to generalise.

Lois has always been excited by colour. Her photographs of fellow students juxtapose parts of people, their midriff usually, with sections of buildings. She attracted by the combinations of colour and texture, but her pictures are also about the role of people and their relationship to buildings. Is the person next to the shop a customer or the shopkeeper? The edges are unclear, visually and conceptually. We enjoy the contrasts and similarities she has noticed in the fabric next to the architecture, of hue, geometry and surface. They are delicious elements; the red is rich, the door is solid and regular, the strangeness of close and far is compelling visually.

The images discussed in this part represent a variety of approaches, categorised for convenience, that might help others to recognise the strategy being employed by a student and so support their work, or offer other routes in. I am sure there are others but these seem to be the most popular and effective with the time, money and resources most often available to the average 16 to 19 year old.

Cropping (and juxtaposition)

The most effective of all the techniques in the photographer’s tool kit is central to how this image works. The top and the bottom of the field of view have been sliced away. The result is abstracted, so we are able to recognise the person in the picture, but it is their presence of a human, clothed and colourful, that carries the meaning rather than the image of any one, single person in particular. The anonymity here is not for privacies sake but rather to de-personalise so as to generalise.

Lois has always been excited by colour. Her photographs of fellow students juxtapose parts of people, their midriff usually, with sections of buildings. She attracted by the combinations of colour and texture, but her pictures are also about the role of people and their relationship to buildings. Is the person next to the shop a customer or the shopkeeper? The edges are unclear, visually and conceptually. We enjoy the contrasts and similarities she has noticed in the fabric next to the architecture, of hue, geometry and surface. They are delicious elements; the red is rich, the door is solid and regular, the strangeness of close and far is compelling visually.

Silhouetting

Another simple way of photographing people without having to deal with many of the obstacles is to obscure identity by darkening or silhouetting the scene. The figure here is still visible enough to be there, but as the focus is on mood and posture and physicality much of the detail (including the face) is unnecessary, and so has been removed.

Jasmine’s image is only just portraiture in that the figure is hardly visible, hardly present even. Are they leaving or entering through the door that we can just about make out? The frame is divided into bands horizontally and the muted tones are reminiscent of Film Noir. It also reminds me of the king reflected in the mirror at the ‘back’ of Velasquez’s famous Las Meninas. Are they intruding, or are we? The movement is a pause, we notice them as they notice us, and we are waiting to see who will make the next move. The suspense is tangible and delightful.

Another simple way of photographing people without having to deal with many of the obstacles is to obscure identity by darkening or silhouetting the scene. The figure here is still visible enough to be there, but as the focus is on mood and posture and physicality much of the detail (including the face) is unnecessary, and so has been removed.

Jasmine’s image is only just portraiture in that the figure is hardly visible, hardly present even. Are they leaving or entering through the door that we can just about make out? The frame is divided into bands horizontally and the muted tones are reminiscent of Film Noir. It also reminds me of the king reflected in the mirror at the ‘back’ of Velasquez’s famous Las Meninas. Are they intruding, or are we? The movement is a pause, we notice them as they notice us, and we are waiting to see who will make the next move. The suspense is tangible and delightful.

Focus

Shooting a photograph with soft focus was always a mainstay of 1930’s glamour – the stretched stockings over the lens, or breathing on it and using the clearing condensation. It is difficult nowadays, with modern cameras, to actually shoot out of focus (as opposed to with soft focus). They’re just not designed for that, let alone over or under-exposure, or blurring. We have to work against the technology to get the images we want or need. But switching to manual focus does the job, and then it’s a case of judging the level of out of focus-ness, or Bokeh (the technical term). Depending on the degree it can be irritating to the eye or perplexing to the mind. Used sparingly and suitably it can give the impression of a dazed view, the hazy impressionistic scene or the mirage.

Alice has made a picture that is of and about photographic portraiture. We are being photographed at the same time as we appear to be photographing our subject. It is a duel, and we might be losing if we can’t focus our camera quick enough. Unless of course the subject is our own reflection, in which case it is a battle against ourselves, intriguingly. Is victory or failure possible in that situation? The fact that the image remains out of focus means that the duel continues indefinitely; a stand off, a stale-mate.

Shooting a photograph with soft focus was always a mainstay of 1930’s glamour – the stretched stockings over the lens, or breathing on it and using the clearing condensation. It is difficult nowadays, with modern cameras, to actually shoot out of focus (as opposed to with soft focus). They’re just not designed for that, let alone over or under-exposure, or blurring. We have to work against the technology to get the images we want or need. But switching to manual focus does the job, and then it’s a case of judging the level of out of focus-ness, or Bokeh (the technical term). Depending on the degree it can be irritating to the eye or perplexing to the mind. Used sparingly and suitably it can give the impression of a dazed view, the hazy impressionistic scene or the mirage.

Alice has made a picture that is of and about photographic portraiture. We are being photographed at the same time as we appear to be photographing our subject. It is a duel, and we might be losing if we can’t focus our camera quick enough. Unless of course the subject is our own reflection, in which case it is a battle against ourselves, intriguingly. Is victory or failure possible in that situation? The fact that the image remains out of focus means that the duel continues indefinitely; a stand off, a stale-mate.

Alternatives

It is possible to explore the idea of people and the figure without having to photograph either actually. Using statues and dolls, both examples of society representing itself physically, are inventive examples. By taking these kinds of subjects students can look at body image and representations of power quickly and easily. Dolls, both male and female, are cheap and easily accessible, and come with their own associations and qualities that can be manipulated or consolidated.

Joe has given long, hard consideration to the problems of portraiture – not a familiar subject for him particularly. He prefers the spectacle of night photography, the technical challenges of shooting with available light. Dealing with models is messy. He has overcome these issues with ingenuity by photographing statues, in the evening, introducing his own light sources. The results appear ancient and modern. They are moody and, well, statuesque.

It is possible to explore the idea of people and the figure without having to photograph either actually. Using statues and dolls, both examples of society representing itself physically, are inventive examples. By taking these kinds of subjects students can look at body image and representations of power quickly and easily. Dolls, both male and female, are cheap and easily accessible, and come with their own associations and qualities that can be manipulated or consolidated.

Joe has given long, hard consideration to the problems of portraiture – not a familiar subject for him particularly. He prefers the spectacle of night photography, the technical challenges of shooting with available light. Dealing with models is messy. He has overcome these issues with ingenuity by photographing statues, in the evening, introducing his own light sources. The results appear ancient and modern. They are moody and, well, statuesque.

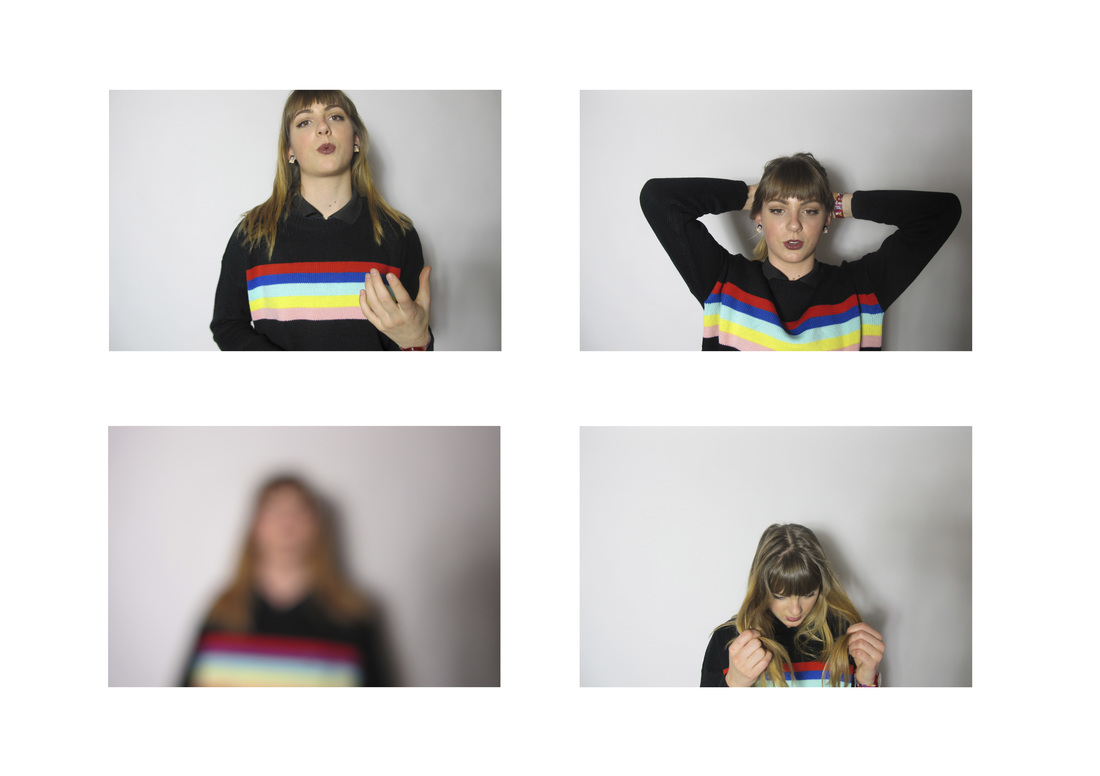

The Studio (and sequences/series)

All photographs are landscape photographs before they are anything else in that we are in the world with the camera, and the ‘empty’ scene is, by default, the landscape. The studio is a veryb particular type of location, chosen for the intensity, intimacy and ultimate control it can offer. Dry, clean, warm – a blank canvas of sorts, though like any other place and space, carries with it all kinds of connotations (fashion, for instance), that need to be acknowledged rather than fudged. Standing a few feet from the subject, with a camera on a tripod, and cable release perhaps, photographers can interact with their models, converse and engage, and record in a unique way. A 90mm – 120mm focal length in ‘old money’ (using 35 mm films cameras, or full-frame DSLRs) gives a head and shoulders composition, without any unflattering distortion and without the need to get ‘up close and personal’ – unless that’s what you’re after!

Alex, attracted by the studio as a controlled environment in which to work, has shown a flare for dealing with the model. The group of four images is inventive photographically; the sequence, the focus, compositions, the action. They allude to glamour and fashion, whilst not feeling overtly commercial. The young woman pictured seems to be explaining or demonstrating something for us. Without subtitles or audio narration we are not sure what though exactly. The pictures depict her attempts and perhaps the failure, at each stage, whilst we look on in sympathetic bemusement. The grid of images tracks the moments in the story when the mood or action changes. It then gets shown as a window, with frames within frames, a story-board of sorts.

All photographs are landscape photographs before they are anything else in that we are in the world with the camera, and the ‘empty’ scene is, by default, the landscape. The studio is a veryb particular type of location, chosen for the intensity, intimacy and ultimate control it can offer. Dry, clean, warm – a blank canvas of sorts, though like any other place and space, carries with it all kinds of connotations (fashion, for instance), that need to be acknowledged rather than fudged. Standing a few feet from the subject, with a camera on a tripod, and cable release perhaps, photographers can interact with their models, converse and engage, and record in a unique way. A 90mm – 120mm focal length in ‘old money’ (using 35 mm films cameras, or full-frame DSLRs) gives a head and shoulders composition, without any unflattering distortion and without the need to get ‘up close and personal’ – unless that’s what you’re after!

Alex, attracted by the studio as a controlled environment in which to work, has shown a flare for dealing with the model. The group of four images is inventive photographically; the sequence, the focus, compositions, the action. They allude to glamour and fashion, whilst not feeling overtly commercial. The young woman pictured seems to be explaining or demonstrating something for us. Without subtitles or audio narration we are not sure what though exactly. The pictures depict her attempts and perhaps the failure, at each stage, whilst we look on in sympathetic bemusement. The grid of images tracks the moments in the story when the mood or action changes. It then gets shown as a window, with frames within frames, a story-board of sorts.

On Location

Whilst the studio can effectively isolate and abstract the subject-model from their environment (although it places them in another) the location allows the locality to be part of the view. It is important I think to differentiate between spaces (generalised, like kitchens or parks) and places (specific, like my kitchen, or Piccadilly Circus). They provide the background, in every sense, carrying information, values and qualities that can then be taken advantage of. The ambient light and the availability of objects as ‘props’ are two obvious examples of how the image can be enhanced and embellished. If nothing else it can be used to put the person, or people at ease (or otherwise!?). It can present them in their ‘natural environment’ (the teacher in their classroom, the goalie in her goal) or a different one to consolidate the view or jar the viewer.

Sophie photographed her friend, for lack of convenient alternatives. She is in an old stock cupboard – it seemed as good a place as any, quiet and secluded. The girl is holding a sculpture she’d made out of drinking straws, and why not?! The space is confined and dimly lit, the student is in contemplative mood, staring at the black triangle in front of her, wearing a think sheepskin coat, with white lapels that match the geometry elsewhere in the frame. It is such an odd photograph, and that is its appeal. We are thinking about what she is thinking about, and we are both asking ourselves why. The question is never answered and so we keep looking.

Whilst the studio can effectively isolate and abstract the subject-model from their environment (although it places them in another) the location allows the locality to be part of the view. It is important I think to differentiate between spaces (generalised, like kitchens or parks) and places (specific, like my kitchen, or Piccadilly Circus). They provide the background, in every sense, carrying information, values and qualities that can then be taken advantage of. The ambient light and the availability of objects as ‘props’ are two obvious examples of how the image can be enhanced and embellished. If nothing else it can be used to put the person, or people at ease (or otherwise!?). It can present them in their ‘natural environment’ (the teacher in their classroom, the goalie in her goal) or a different one to consolidate the view or jar the viewer.

Sophie photographed her friend, for lack of convenient alternatives. She is in an old stock cupboard – it seemed as good a place as any, quiet and secluded. The girl is holding a sculpture she’d made out of drinking straws, and why not?! The space is confined and dimly lit, the student is in contemplative mood, staring at the black triangle in front of her, wearing a think sheepskin coat, with white lapels that match the geometry elsewhere in the frame. It is such an odd photograph, and that is its appeal. We are thinking about what she is thinking about, and we are both asking ourselves why. The question is never answered and so we keep looking.

So photographs of people, those that show us more than outward appearance, are possible and useful. Cameras can only ever really depict a momentary illuminated surface, but the photographer can suggest or refer to other qualities that deepen and widen our knowledge of the subject. What we look like, at that precise moment, from one singular and particular vantage point, might be a failure to record other human characteristics or qualities that make us who we are. They might even further obscure or distort appearances. I’d argue that what we look like could even be the least important or valuable piece of personal information we can glean from a photograph. Emotions, the sound of our voice, our attitudes can be alluded to, but it is only ever that, an allusion. The process of photographing others holds the power to place us in a position of better understanding our fellow beings, even if it just the licence it gives us to ask certain questions, or the permission if offers the subject, strangely, to ‘be themselves’. I am coming around to the idea that what people look like, in the flesh as it were, might be their least interesting asset, and that my camera needs to be aimed at showing people without the need to see them. That’s an interesting problem; it does away with much of the ethical and the logistical barriers too, but in their place introduces visual problems no less complex. But is it just a refusal on my part to face the problems that portraiture poses?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

There are many books on portraiture in photography, and self-portraiture as a sub-category. What follows here is by no means exhaustive (indeed it is very short) but does offer an introduction, for teachers and students, to some of the well-written and useful literature on the subject. It should also provide the opportunity to begin exploring some of the theory involved (ethics, the gaze etc.) Some are more practical with illustrations to explain whilst others are more essay-based, but hopefully no less accessible.

I have not included references to texts on specific photographers here. Many are mentioned in part one, some if not all readers will be familiar with. There wasn’t the space or opportunity to mention others that I believe are operating at the very edges of the form, producing really fresh and adventurous work, photographers such as Betina Von Zwehl, Gillian Wearing, Thomas Struth and Paul Graham. I very much hope that this essay encourages readers to explore deeper the work of others, but also as a means of developing their own practical responses in photographic portraiture.

Read This If You Want To Take Great Pictures Of People, Henry Carroll (2015)

Auto focus: The Self-Portrait In Contemporary Photography, Susan Bright (2010)

Face: The New Photographic Portrait, William A. Ewing (2006)

Photography: Key Concepts, David Bate (2009) – Chapter 4 (Looking at Portraits)

The Photograph: A Visual and Cultural History (1997) Graham Clarke – Chapter 6 (The Portrait in Photography)

I have not included references to texts on specific photographers here. Many are mentioned in part one, some if not all readers will be familiar with. There wasn’t the space or opportunity to mention others that I believe are operating at the very edges of the form, producing really fresh and adventurous work, photographers such as Betina Von Zwehl, Gillian Wearing, Thomas Struth and Paul Graham. I very much hope that this essay encourages readers to explore deeper the work of others, but also as a means of developing their own practical responses in photographic portraiture.

Read This If You Want To Take Great Pictures Of People, Henry Carroll (2015)

Auto focus: The Self-Portrait In Contemporary Photography, Susan Bright (2010)

Face: The New Photographic Portrait, William A. Ewing (2006)

Photography: Key Concepts, David Bate (2009) – Chapter 4 (Looking at Portraits)

The Photograph: A Visual and Cultural History (1997) Graham Clarke – Chapter 6 (The Portrait in Photography)