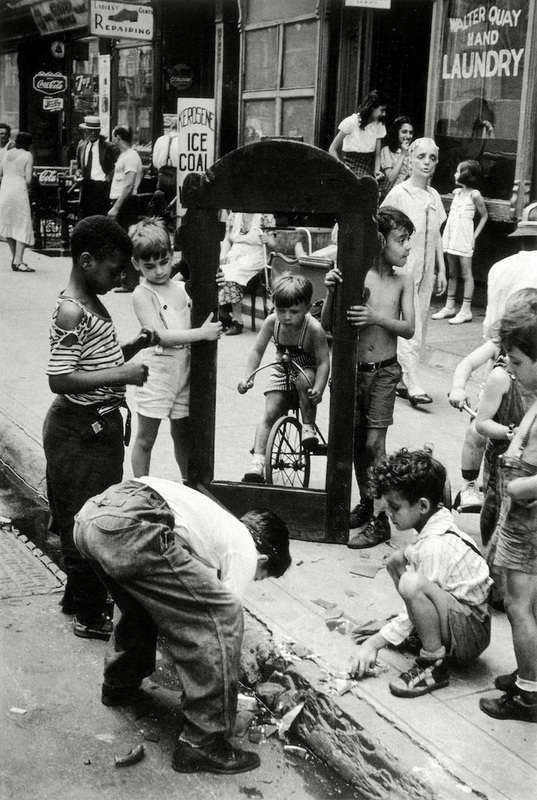

Helen Levitt 'New York' c.1945

DISCUSSION PROMPTS:

|

Among the urban themes explored by artists of widely varying sensibilities were these: the physical city, an artefact shaped by the impress of innumerable lives; the symbolic city, in which issues of community and identity are reflected in solitary figures and masses of anonymous faces; and the poetic city, in which the larger meaning of modern existence is revealed in the disjunctions, flux, and contingencies of urban life. The work of many of these photographers reveals a basic sympathy with the much earlier observations of the poet Charles Baudelaire on the relationship of the modern artist to the spectacle of urban life:

For the perfect flaneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and infinite. To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world ... the lover of universal life enters into the crowd as though it were an immense reservoir of electrical energy...

For Baudelaire, the key words were: Multitude, solitude: equal and convertible terms for the active and fecund poet. He who does not know how to people his solitude will not know either how to be alone in a bustling crowd. The poet enjoys the incomparable privilege of being able as he likes to be himself and others. Like those wandering souls which search for a body, he can enter every person whenever he wants .... The solitary and pensive walker draws from this universal communion a singular sense of intoxication."

No photographer is more typical of this approach than Helen Levitt, whose lyrical work was a direct result of her love of walking and her desire to immerse herself in the "fugitive and infinite" vitality of the street. A deeply private person, Levitt photographed strictly for her own pleasure and belonged to no organised groups. She was influenced by her close friendships with Walker Evans and Ben Shahn, and later, by certain visual techniques she developed in her work in film. "' In 1935, she was strongly impressed by the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, the great exponent of the 35mm Leica camera. Levitt's own photographs were also made with a Leica, which she often equipped with a right-angle viewfinder. This practice allowed her to work unobtrusively, almost invisibly -in the poor or working-class communities of New York City. In these neighbourhoods, the rhythms of daily life were played out in full view on public sidewalks. Levitt responded to this protean theatre of the street by creating photographs that are lyrical, uncontrived, and mysterious. Fascinated by the simplest marks and the most fleeting gestures, Levitt made images of children's graffiti that suggest the timeless human need for self-expression, as well as the surprising insights of un-selfconscious artists. Other works, like New York, Ca. 1942, subtly explore the complex network of connections between individuals and their surroundings. In this case, Levitt creates a gentle mystery from the evidence of touch, expression, and glance, while using internal framing devices to hint at the constraints of these lives. Levitt received high critical praise in the 1940s: her pictures were published in and elsewhere and exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art. Unfortunately, however, the first book of her photographs did not appear for many years: A Way of Seeing, a selection of forty-four uncaptioned images with an eloquent essay by James Agee, was assembled in 1946 but not published until 1965.

from Keith F. Davis, An American Century of Photography: From Dry-Plate to Digital: The Hallmark Photographic Collection