Post 16 Lesson Plan:

By Chris Francis, St Peter's School

This lesson (Part 1 of 2) delves deeper into some of the more popular themes for portraiture that can arise in the classroom. Aimed at Year 12 and 13 students, it sets out to provoke deeper questioning and reflection on these approaches, and also the definitions and possibilities of the portrait genre. Part 2 will consider formal and informal approaches - from objective recordings to a snapshot aesthetic - unpicking the benefits of portrait-related projects as a means of building student confidence.

Portraits. Where to start with such a rich and complex theme? Give a chimp a camera and they’ll likely point it at a fellow anthropoid, or themselves, eventually. But whether monkeys maketh a portrait or not I'll leave you to decide. In fact, establishing the boundaries for what constitutes a portrait or not is as good a place to start as any.

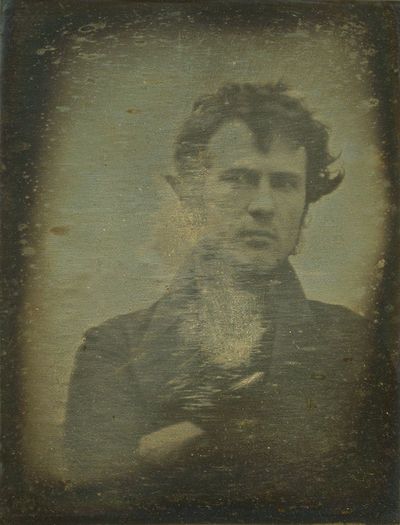

Robert Cornelius was certainly no chimp. As taker of the earliest surviving self-portrait he provides the obvious starting point for our popular resource, The Selfie. No doubt that such indulgences are a form of portraiture - potentially, fellow 21st century narcissists, the most common of all - but as they've been dealt with in that lesson, let's eliminate ‘Selfies’ from this one. Some narrowing down can only help.

|

So what does constitute a portrait? Threshold Concept 1 reminds us that Photography has many genres, some old, some borrowed, some new. And while for ease of introduction 'Portraits' might be considered one of the big three inherited from art - alongside 'Landscape' and 'Still Life' (other genres available) - the boundaries between these aren't always obvious.

Introductory Questions

|

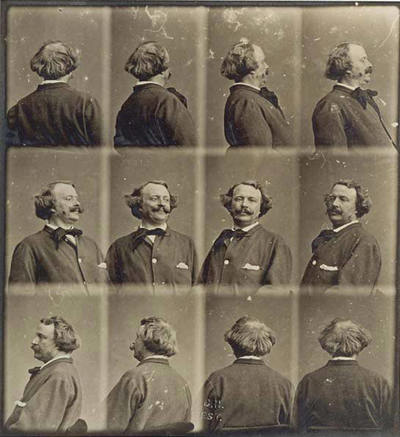

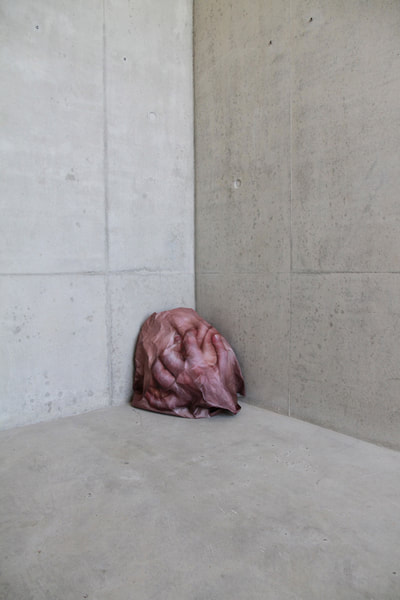

Consider the images below and discuss their suitability for being described as portraits. What qualifies or discounts these as portraits? How might the reasons and contexts for these images vary? Which are you most drawn to, and why?

Photographs of people surround us. Faces stare out of our newspapers, news feeds, social media accounts, billboards, packaging, and so on. We - our faces, bodies, actions, interactions, belongings - are photographed daily, be it by ourselves, our friends, family, or via security cameras or facial recognition software. Photographs of faces serve practical purposes too: passports, identity cards, driving licenses and so on. All this exposure adds up. From these seemingly sterile mugshots to the flirtatious in-our-face faces of advertising; the portraits we encounter all play a part in shaping our own sense of place and belonging.

With reference to some of the images above, here are a few prompts to provoke further research and discussion:

With reference to some of the images above, here are a few prompts to provoke further research and discussion:

- Maija Tammi’s portrait of the android, Erica, above, bottom right, was a contentious entry into The Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize 2017. Some considered this a breach of a clear rule: all entries must contain a person. Should Tammi's image have been included?

- Which of the images above have been taken without the subjects' co-operation or agreement to participate? How do you know this? Is this a significant factor in deciding if the photograph is a genuine portrait (or not)?

- Should a portrait photographer always collaborate honestly with their subject? Should there be an agreement on how they will be represented? Who should own the rights to a portrait - the photographer or the person that has been photographed?

Portraits, of a fashion

Fashion Photography is a common inspiration for portraiture in the photography classroom. But this genre can also provoke student antics worthy of discouraging. Skin-deep approaches - when students want to simply doll up and pose away (or choose others predisposed to do so) - should be met with relative incision. An autopsy on fashion photography's dark heart usually does the trick. Open up the rich and complex history of this genre - relevant to broader themes of portraiture too: propaganda, prejudices, misogyny, manipulations and so on - and, consequently, students can be challenged to create portraits in response to more complex themes rather than naively mimic (often inappropriate or embarrassing) catalogue poses.

Above are a few contemporary examples of works that hint at how experimental this field has become; below are a few prompts that might lead towards wider research and reflection.

Above are a few contemporary examples of works that hint at how experimental this field has become; below are a few prompts that might lead towards wider research and reflection.

Questions, of a fashion

In 1975 feminist film critic Laura Mulvey coined the term, the 'male gaze'. This was in reference to the act of depicting women as objects of male pleasure. The history (his-story, even) of fashion photography certainly elevates male photographers over female and - notoriously - has often been accused of promoting overly-sexualised imagery, alongside evoking feelings of negative self-image.

An introductory lesson resource relating to Fashion photography is available here.

- Does the objectification of women remain an issue within the portraits that surround us today? Is fashion photography (and wider advertising) preoccupied with certain stereotypes or narrow perceptions of beauty? (Does this apply to all genders?).

- What approaches/styles/techniques/devices do the contemporary fashion photographers (above) adopt which may give these portraits a more contemporary feel? Useful words to consider (research if required) might include: Post-modern, absurd, ironic, evocative, layered, multifaceted. You might also consider terms relating to genres and styles, for example: snapshot aesthetic, (faux) documentary, staged, objective, digital montage, manipulated.

- What is it like to take a portrait of a stranger? How might your behaviours and feelings change depending on the familiarity, gender, age, or status of the model?

An introductory lesson resource relating to Fashion photography is available here.

Beware: Portraits, manipulated

Now, don't scrunch your face up. Teachers (and keen-bean students who've got this far), we need to talk about something. It's this: the Pinterest-inspired quick-fix portrait lesson. And don't pretend you don't know what I mean.

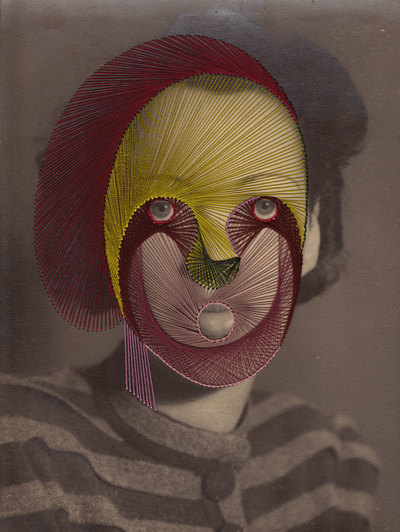

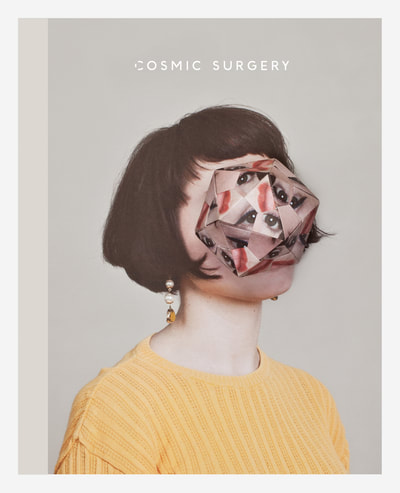

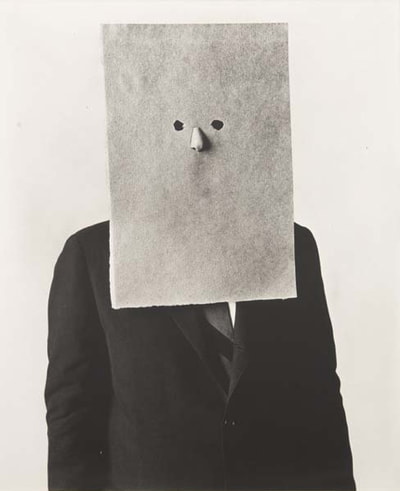

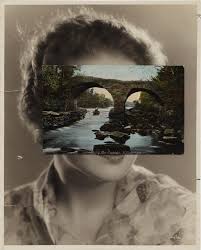

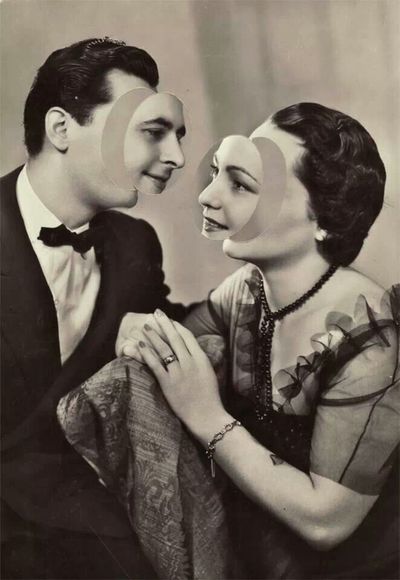

The artworks of Maurizio Anzeri, Alma Haser and Stephen J Shanabrook (above, for example, others are below) are popular inspirations in art rooms across the land. It's easy to see their appeal. For teachers and students alike, these works are striking and playful, and not without craft either. But how to tread that fine thread between inspiration and unimaginative copying?

Appropriate, manipulate, collage, embellish, tear, layer, join, puncture, shred, weave... I could go on, I - we - love these words. Here lie endless possibilities for portrait experiments, with the potential to connect to rich histories too - from indigenous crafts to Cubism; Dada to Décollage; Pevora to Pop Art, and beyond.

So what's not to like? Perhaps just a little more caution is now required to ensure that students (and ourselves, teachers) are not just half-heartedly recycling the ideas of others.

Here's some suggestions on how a richer balance might be met:

And if that sounds a bit daunting to begin with, some example questions are included below...

The artworks of Maurizio Anzeri, Alma Haser and Stephen J Shanabrook (above, for example, others are below) are popular inspirations in art rooms across the land. It's easy to see their appeal. For teachers and students alike, these works are striking and playful, and not without craft either. But how to tread that fine thread between inspiration and unimaginative copying?

Appropriate, manipulate, collage, embellish, tear, layer, join, puncture, shred, weave... I could go on, I - we - love these words. Here lie endless possibilities for portrait experiments, with the potential to connect to rich histories too - from indigenous crafts to Cubism; Dada to Décollage; Pevora to Pop Art, and beyond.

So what's not to like? Perhaps just a little more caution is now required to ensure that students (and ourselves, teachers) are not just half-heartedly recycling the ideas of others.

Here's some suggestions on how a richer balance might be met:

- By digging deeper into the histories of various techniques, acts of creative manipulation, intervention and disruption;

- through questions and experiments that test and expose the physicality and material nature of photographs (alongside the surface and illusionary qualities);

- by honestly reflecting upon our conscious and sub-conscious responses to photographs, particularly when the subject matter is another person.

And if that sounds a bit daunting to begin with, some example questions are included below...

Going deeper, beyond the manipulated surface

Questions to provoke deeper reflections on manipulated portraits, with reference to the popular images and techniques above:

- If you had two photographs - one of a freshly-faced smiling baby, the other of a tyrant (Hitler, for example) - would it be easier to stick a pin in the eye of one over the other? It's a brutal question, but one that can reveal how portraits have a hold upon us.

- What makes a particular portrait best-suited for manipulating - and how might the technique chosen have an affinity with - or contrast with - the original image?

- Consider this: what would it mean to watch a stranger (or an enemy, or a friend) deface the portrait of a loved one? We tend to dismiss ideas of voodoo as hocus-pocus, but can photographs evoke primitive fears and deep or irrational connections?

- What is so appealing about distorting, disrupting and manipulating images? Which of the approaches above would you consider: the most planned; most creative; most skilled; most contemporary; most traditional? And which would you most like to physically touch or move around to view?

- How would you describe each portrait above? Consider how fitting the following words might be: funny, playful, mystical, methodical, crafted, abstracted, surreal. What other words might you use?

- We tend to accept - ignore, even - that printed photographic portraits are flat surfaces. But when these flat surfaces are manipulated, folded, raised (as above) this illusion is broken. Do these photographs then become something more sculptural, more 'art-like'?

- Do the portraits above tell us more about the artist than the subject, and if so, what information is gained (or lost)?

- Why is the appropriation of 'vintage' imagery so popular? (And what is it with that word?).

For further lesson resources based on manipulated portraits see the following contributions: The Art of Destruction, Portrait Distortions, Cut & Paste.

Suggested Activity:

|

This task is to encourage students to carefully think about the images they chose to manipulate, and the act - performance -of manipulating itself. The work (and instagram feed) of Kensuke Koike can be a useful starting point.

Ask students to:

|

Above is a playlist of responses by Year 12 students from St Peter's School, Bournemouth.

|

Further resources: Playful, practical ideas

The examples below have been selected from a slideshow originally created for our Class Photo, Tate Exchange CPD event. These share further lesson ideas and student outcomes relating to the portrait themes above.

Part 2 of this portrait-themed resource will focus on:

If you have found this lesson or further resources on this site of benefit, please do consider making a donation . All funds raised contribute directly to our work for young people and teachers.

If you'd like to share your own thoughts, lesson insights, experiences, or student work, you can do so here.

- Engaging with others through portraiture

- Practical considerations when taking portraits

- Formal and informal approaches to portraiture

If you have found this lesson or further resources on this site of benefit, please do consider making a donation . All funds raised contribute directly to our work for young people and teachers.

If you'd like to share your own thoughts, lesson insights, experiences, or student work, you can do so here.