Post 16 Lesson Idea:

By Chris Francis, St Peter's School

Rather than focusing on one distinct theme, this lesson uses four key starting points and invites students to make sensitive connections between them. The starting points are as follows:

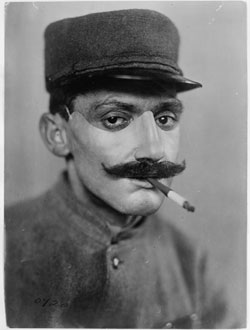

- Remembrance Day - in particular, the portraits of WWI soldiers taken prior to heading off to war. Often gifted to loved ones, these are poignant images, romantic and palatable.

- The Tin Noses Shop - the nickname given to a post-WWI hospital ward initiated by artists, dedicated to creating facial masks to conceal horrific facial injuries sustained in war.

- The portraits of JR, artist/photographer - specifically his embracing of portrait photography as a means of improving the world and our relationships within it.

- A mirror - used to reflect upon and consider our facial features (and those of others), and what is considered presentable or not.

Below are further insights and links related to each of these starting points. A range of questions and practical suggestions are also provided. A suitable challenge for students is to research these aspects further and to then develop a collaborative response.

Remembrance Day

Remembrance Day is a memorial day for all those who have died in the line of duty since World War I. It is observed on 11 November, the date that marked the end of hostilities in 1918 - "at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month", in accordance with the armistice.

Below are a couple of prominent Remembrance artworks with specific reference to World War I. These were created as part of the Centenary commemorations of 2018. Click on the images for further information:

Below are a couple of prominent Remembrance artworks with specific reference to World War I. These were created as part of the Centenary commemorations of 2018. Click on the images for further information:

|

For reflection:

|

Art to remember

Over the past 100 years, tracing back to ancient civilisations, art has always emerged from conflict. From urgent frontline recordings to deliberate acts of protest; from commissioned propaganda to personal outpourings of grief, anger, bewilderment or otherwise. War is comprehensive with emotions, and art enables us to prepare, document, express, manage and remember. War and art - and photography too, at least since the mid 1800s - share entwined and bloodied histories. Consider the historical images, above, and the more contemporary responses, below, and follow the links for further information.

|

|

14-18 NOW is a five-year arts programme designed to connect people with the First World War. To date, 14-18 NOW has commissioned over 325 artworks from leading contemporary artists, musicians, designers and performers. This video gives an insight into the range, scale and ambition of some of the projects.

|

Photographs, to remember

Photography in the First World War was made possible by earlier developments in chemistry and in the manufacture of glass lenses, established as a practical process from the 1850s onwards. Photography was a growing popular hobby by 1914, chiefly among the middle classes. Some mass-circulation newspapers printed photographs as part of their news coverage, for which they employed professional photographers. Many soldiers going off to the war had a photograph taken of themselves in uniform, often a studio portrait taken by a professional; many also carried a photograph of a loved one with them. But most people were still rather formal and camera-conscious, and smiling for the camera was not usual. Source: Stephen Badsey, The British Library

Many photographs were taken over the period of WWI and the camera was utilised - and restricted - for numerous reasons. Arguably, if photographs of the horrors of war were more readily available at the time of subscription uptake and anticipations would have been significantly altered. As it was 'The Great War' marks the emergence of photographs as influential artefacts - weapons, even - to document, survey, persuade, haunt...and remember. The photographs above are studio portraits of soldiers taken prior to heading off to battle. These include British, German, Australian, Indian and African American soldiers (lest we forget that this was a global, multi-cultural war). These photographs were most likely taken as keepsakes for loved ones. Tragically, many soldiers who were photographed did not return home while those that did were often unrecognisable in comparison, in mind and appearance.

The Tin Noses Shop

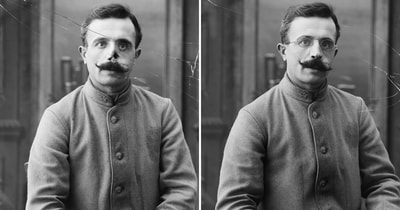

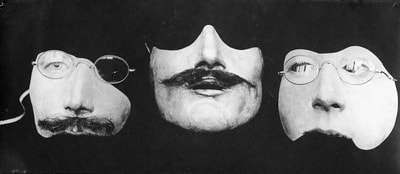

An estimated 60,500 British soldiers suffered head or eye injuries during WWI, often a result of gun shot directly in the face. Sir Harold Gillies was a pioneer in the art of facial reconstruction who worked within a specialist hospital for facial injuries in south-east London. Recalling his war service he stated: "Unlike the student of today, who is weaned on small scar excisions and graduates to harelips, we were suddenly asked to produce half a face."

But even with the remarkable work of Gillies and his team, many soldiers remained disfigured beyond recognition. This unimaginable torment often resulted in a severe sense of isolation from the world. The Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department or the Tin Noses Shop, as it became known among servicemen, offered some hope.

But even with the remarkable work of Gillies and his team, many soldiers remained disfigured beyond recognition. This unimaginable torment often resulted in a severe sense of isolation from the world. The Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department or the Tin Noses Shop, as it became known among servicemen, offered some hope.

Founded by artist and sculptor Francis Derwent Wood, the Tin Noses Shop provided the opportunity for life-like masks to be constructed, albeit through a complex and time-consuming process. Toward the end of 1917, Wood's work was brought to the attention of an American sculptor, Anna Coleman Ladd who went on to open the Studio for Portrait Masks in Paris, administered by the American Red Cross.

"The patient acquires his old self-respect, self assurance, self-reliance,...takes once more to a pride in his personal appearance. His presence is no longer a source of melancholy to himself nor of sadness to his relatives and friends." The film footage, right, shows Anna Coleman Ladd at work in her studio, developing a mask for an injured soldier.

|

|

For reflection

- What might it feel like to look in the mirror and find yourself unrecognisable - and then, less accepted by society for your new appearance?

- At times of remembrance, is it appropriate to reveal, via portrait photography, the devastating effects of war? As time passes is there a danger that photos of pre-injured WWI soldiers become overly-romanticised?

- As objects made by artists, can these masks be described as art? As isolated objects - retaining respect to context - do these fragmented face-parts have an appealing visual or surreal quality?

|

Practical Activity

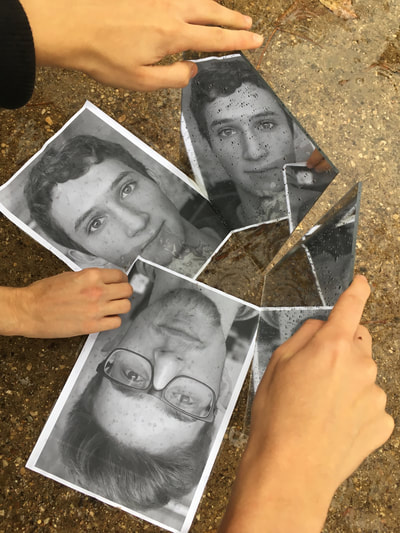

In response to - and utilising - researched photographs of WWI soldiers, create a series of collaged or digitally manipulated experiments that explore these powerful themes. You might consider:

How might your collage experiments embrace a variety of techniques or media to add physical and conceptual value and depth? What words, objects or additional imagery might you add to reveal your own thoughts - to show a more subtle understanding of these complex themes? Does your collage have to be permanently fixed? Could the components be interactive so that you (or others) could explore various layouts and possibilities, photographing different arrangements and paying attention to how potential meanings might shift? Where might you be able to present or share your work to encourage others to think about themes of remembrance? |

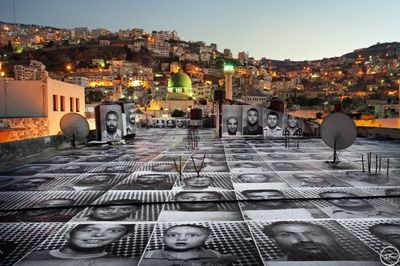

The portraits of JR

JR is a French artist, photographer and film maker who has produced an awe-inspiring body of work that combines photography, street art and installation with a commitment to positive action. His highly ambitious and collaborative projects tackle challenges with scale, location and political and social concerns, and deal with issues such as commitment, freedom, identity and limits. Click on the images below for further information.

|

|

JR's work came to wider prominence following his TED talk in 2011 in which he shared his wish to 'Use Art to turn the world inside out'. Since, he has produced a remarkable body of work in response to a wide range of social concerns including immigration, equal rights and the conflict in the Middle East. More recently (and perhaps most relevant to these resources) JR was commissioned by TIME magazine to create a special report, 'Guns in America'. This has included a complex (animated) cover design, a touring mural, and an explanatory film, below.

|

For reflection:

- Is it possible for art - or artists - "to change the world"? Which works of art/photographs come to mind as being particularly influential?

- How might you set about changing the world for good - or at least to begin with, something within your immediate environment? How might you create work that is of benefit to others?

Mirror, mirror

The resources above provide rich starting points for reflection: the significance of Remembrance Day; the relationships between art and remembrance; the potential of art - and the actions of artists - as a force for good in the world. But the word 'reflection' has a dual meaning, most commonly associated with mirrors and the throwing back of light.

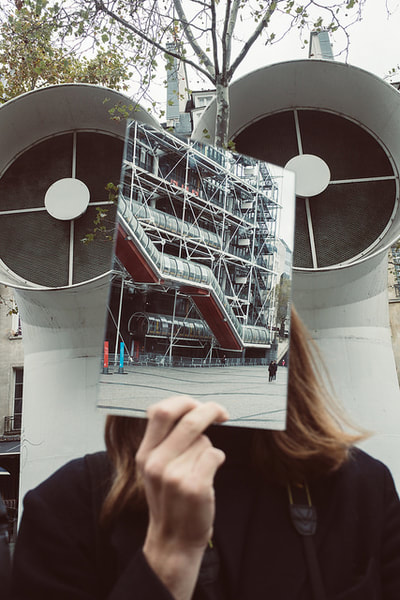

From a practical perspective, mirrors allow us to see ourselves and how we might appear to others, to look in alternative directions; to playfully fragment and distort reality. Mirrors have played a central part in many artworks, as compositional devices - such as within Édouard Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (or Jeff Wall's Picture for Women) and Diego Velázquez's Las Meninas (or Joel-Peter Witkin's alternative take) - but also utilised for collage, sculpture, installation and performance - such as Anish Kapoor's Sky Mirror and Joan Jonas's Mirror Check. In addition, many cameras - typically single-lens reflex cameras - use a mirror system to enable us to see what will be recorded.

Practical provocations

- How might a mirror, a set of mirrors, or a reflective surface be utilised to experiment with themes of Remembrance and portrayal?

- How might you use a mirror to create an alternative 'reflection' - a way of bringing together alternative viewpoints, perspectives, periods of time, or identities?

- Within small groups consider how you might use mirrors and additional materials to create a collaborative Remembrance artwork or performance. Suitable resources might include printed portraits of yourselves; pre-war portraits of WWI soldiers; scissors, string, tape etc. You might want to use phones to record audio for replaying or layering, or consider imaginative ways of documenting and recording from multiple viewpoints.