Post 16 lesson plan:

Exploring the relationship of the parts to the whole in photography.

From Jon Nicholls, Thomas Tallis School

|

At the risk of seeming wilfully obscure, the idea for this mini project comes from one of my favourite words, "synecdoche", a linguistic term, and wondering whether it was possible to think of a photographic equivalent of it. Synecdoche is defined as follows:

A synecdoche (si-nek-də-kee) is a figure of speech in which a term for a part of something refers to the whole of something or vice versa. A synecdoche is a class of metonymy, often by means of either mentioning a part for the whole or conversely the whole for one of its parts. Examples from common English expressions include "bread and butter" (for "livelihood"), "suits" (for "businesspeople"), and "boots" (for "soldiers"). Threshold Concept #4 suggests that photography is an art of selection rather than invention. Photography is unlike other visual arts in that it begins with a world full of things rather than with a blank slate.

|

These fragments I have shored against my ruins

In what sense, therefore, are all photographs parts or fragments, of a much larger whole? If the photographer starts with the whole world, framing small sections, aren't all photographs kinds of synecdoche? What kinds of relationships do individual photographs (or sequences of photographs) have to much larger subjects? Are some photographs more successful synecdoches than others?

|

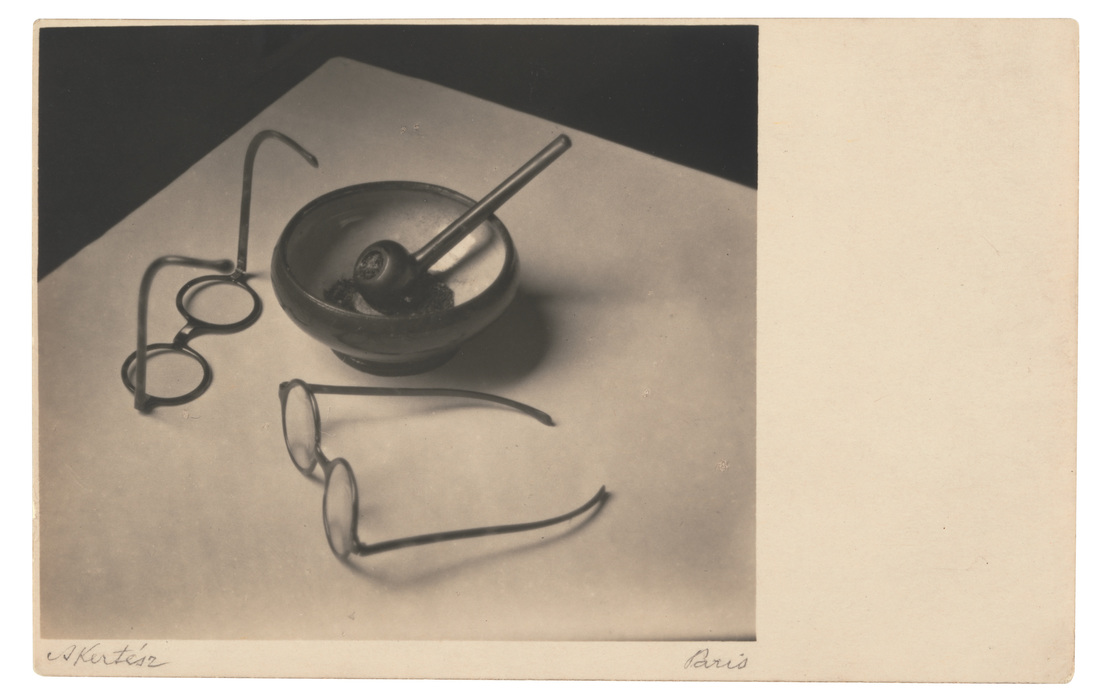

Take this photograph by André Kertész of the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian's pipe and glasses, for example. In what sense are the objects in this image parts of the identity of Mondrian and, therefore, representative of the painter?Mondrian was rarely seen without his trademark glasses and pipe. They suggest a studious, serious personality. The stark simplicity of the photograph's composition, the repetition of shapes (glasses, pipe, bowl) contained by the edge of the white table top might, if we were familiar with Mondrian's abstract paintings, also contribute to our understanding of the man who is physically absent from the picture.

Think of someone you know well. Would it be possible for you to construct a photographic portrait of this person without them being present? What objects might you choose to represent them? How few would you need to make identification almost certain? How would you choose to photograph them? |

Needing a hand

|

(i do not know what it is about you that closes

and opens; only something in me understands the voice of your eyes is deeper than all roses) nobody, not even the rain, has such small hands -- e.e.cummings |

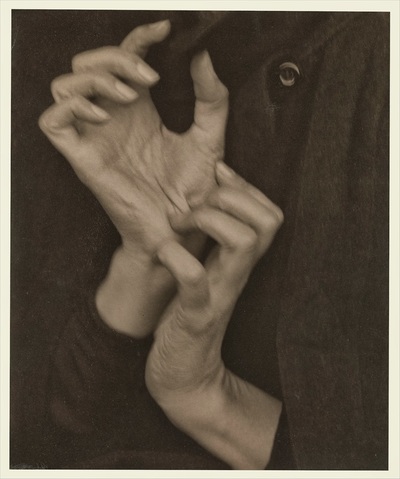

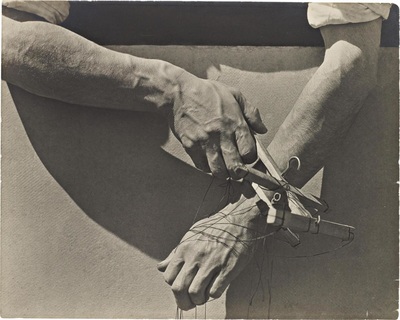

Renaissance painters were probably the first artists to realise the importance of hands as a source of emotional power. As artists became more famous, employing a team of assistants to complete their many commissions, the master would always be responsible for the finishing touches, giving particular attention to the hands. Hands are extraordinarily expressive, indicating everything from a state of grace to inner torment. Poets, especially writers of sonnets, use synecdoche to describe their lovers in terms of isolated body parts. Some photographers have been particularly interested in photographing the hands. Take a look at these examples.

What do these pairs of hands represent? How have they been framed? Experiment with creating your own photographs of hands. Think about your proximity to the subject, the angle of the camera, the edge of the frame, the idea or emotion you wish to communicate.

A sad poem

Of course, it's not just people who might be represented by parts of a whole. I came across the word "synecdoche" again recently in Susan Sontag's 'On Photography' where the writer describes the problem faced by American photographers attempting to deal with the vastness of their country. Whereas Europeans, she argues, are at home in their countries (she cites August Sander's ability to categorise German society in his famous portrait sequence), Americans, by contrast, are overawed by theirs. They are foreigners in their own land. America is simply too big to categorise. Consequently, the only way they can begin to describe it is by using parts to represent the whole (i.e. using synecdoche):

Americans feel the reality of their country to be so stupendous, and mutable, that it would be the rankest presumption to approach it in a classifying, scientific way. One could get at it indirectly, by subterfuge - breaking it off into strange fragments that could somehow, by synecdoche, be taken for the whole.

-- Susan Sontag

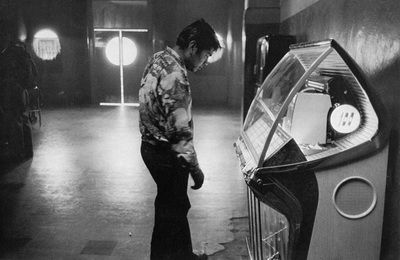

Robert Frank, in The Americans, uses a range of objects to represent the America he witnessed in the 1950s, jukeboxes being, perhaps, the best example:

We might describe this approach as poetic. The jukebox is a synecdoche, a kind of metaphor, each one reminding us of previous jukeboxes and the web of accumulated emotions we associate with them. The jukebox is quintessentially American - shiny chrome and glass, artificial lights, Rock 'n' Roll, loud and brash. It's simultaneously a symbol of glamour and youthful rebellion. But it's also a sign for loneliness and thwarted dreams, providing a Blues soundtrack for drowning your sorrows. As Jack Kerouac writes in the introduction to 'The Americans':

That crazy feeling in America when the sun is hot on the streets and music comes out of the jukebox or from a nearby funeral [...] After seeing these pictures you end up finally not knowing any more whether a jukebox is sadder than a coffin [...] Anybody doesnt like these pitchers dont like potry, see [...] Robert Frank, Swiss, unobtrusive, nice, with that little camera that he raises and snaps with one hand he sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film...

-- Jack Kerouac, from the introduction to 'The Americans'

Microscosm/macrocosm

Another example of visual synecdoche can be found in the work of British photographer, Peter Fraser. His approach is reflected in Jean Cocteau's description of a poet:

The job of a poet, a job that cannot be taught, involves placing objects from the visible world, rendered invisible by the eraser of habit, in an untoward position that strikes the soul and imbues it with tragedy. One therefore needs to compromise reality, to catch it out, to flood it unexpectedly with light and to make it reveal what it is hiding.

-- Jean Cocteau

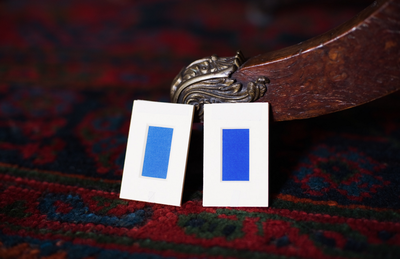

Here are some images from his series 'Lost for Words' from 2010:

But how do we escape the "eraser of habit"? Fraser is interested in the way our subconscious mind can play a part in the process of selecting subjects suitable for photography. We may be drawn to something visually without fully understanding why. We may be "lost for words" but able to recognise the mysterious visual lure of an object or scene. Some detail, a patch of colour, an object out of place, an object from a dream, can mysteriously arrest our attention. As long as we are paying attention of course. Making a photograph, almost by instinct, is a way to mark and honour this moment of recognition. Later on, when we review, select and sequence our images, we can begin to wonder about what we saw and photographed, trying to make some sense of the ways in which these small parts make a more coherent whole. Fraser looks at the world at very close range. His eye is microcosmic.

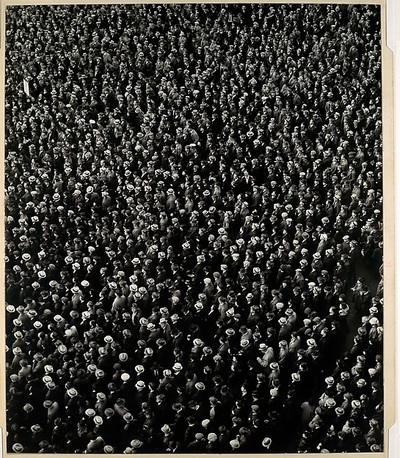

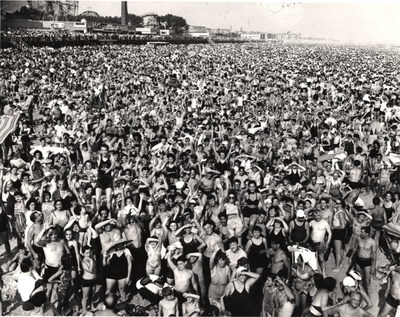

So what about that other meaning of synecdoche, the macrocosmic rather than the microcosmic, whereby the whole is used to represent one of its parts? Might there be a photographic equivalent of that? Take these two famous images of crowds, for example:

Compare these photographs with the massive, digital composites of Andreas Gursky:

Sometimes, photographers take a step back in order to get the big picture. What happens when we attempt to gain a wider view of life? What's it like to look at photographs like those above? For me, it's a strange, slightly vertiginous experience. I'm seduced by the abstract beauty of the entire image - the patterns, the repetitive rhythm, the all-overness. But it's not long before I'm scouring the surface of the photograph for details, looking for anomalies, searching for the unusual amongst the typical, attempting to find an invisible Wally, something or someone I recognise, a visual foothold.

Take the striking crowd of workers, for example. What appears to be a faceless mass is made up of individuals with livelihoods, worries, political allegiances. The crowd at the beach, packed together like sardines, are really a diverse gaggle of New Yorkers, as different as chalk and cheese. When photographers capture the massive or monumental are they also attempting to say something very specific, depicting the whole in order to represent a little part? Every big picture is filled, after all, with tiny details.

Take the striking crowd of workers, for example. What appears to be a faceless mass is made up of individuals with livelihoods, worries, political allegiances. The crowd at the beach, packed together like sardines, are really a diverse gaggle of New Yorkers, as different as chalk and cheese. When photographers capture the massive or monumental are they also attempting to say something very specific, depicting the whole in order to represent a little part? Every big picture is filled, after all, with tiny details.

Knowing that you don't know is the first and most essential step to knowing, you know?

|

Synecdoche, New York is a film by Charlie Kaufman. The title is a pun on Schenectady, a small suburb of the city. It's a complex film, a rumination on life and death, in which a struggling theatre director creates a monumental play in a rented aircraft hangar. It's a film about the dangers of not noticing the little things and obsessing about the big things. Time moves unconventionally. We begin to wonder what's real and what's illusory, what's symbolic and what's plain whimsical.

If you're still struggling with the concept of synechdoche, this film won't help much. But, like Peter Fraser's enigmatic photographs, we are constantly reminded of the poet's ability to "compromise reality" by noticing the parts that make up the whole, building a complex web of meaning from tiny details. |

|

Some suggested activities:

- Collaborate with someone you know well. Try to create a portrait of them without photographing them directly. You might choose to photograph objects they own, places they have been, the trace of their presence, parts of their body...etc.

- Think about the place where you live (a district, village, town or city). Attempt to create a photograph or series of photographs that represents the essence of the place. Aim to get below its surface, to suggest the spirit of the place. Notice surprising or characteristic details. Walk the streets with your camera - what strikes you? Allow your subconscious to select subjects for you. Photograph instinctively. Remember, this is not meant to be a set of pictures that might appear in a tourist brochure or promotional advertisement.

- Recall a powerful memory - a childhood holiday, time spent with a companion, a new school etc. Try to remember your feelings and any sensory information - colours, temperature, textures, scents, tastes etc. Now, try to create a photograph or series of photographs that recreate the feelings associated with that memory. Avoid literal photographs and aim for a poetic equivalent.

- Create a series of photographs of a particular day in your life. Which moments/subjects will you memorialise with an image? How many pictures will you take in total? How many pictures will you select as representative of the day?