What is photography?

By Jon Nicholls

One of the many exciting challenges in teaching photography at whatever level is getting students to think hard about the nature of the subject. Why is this important? I think there are several possible answers to this question:

|

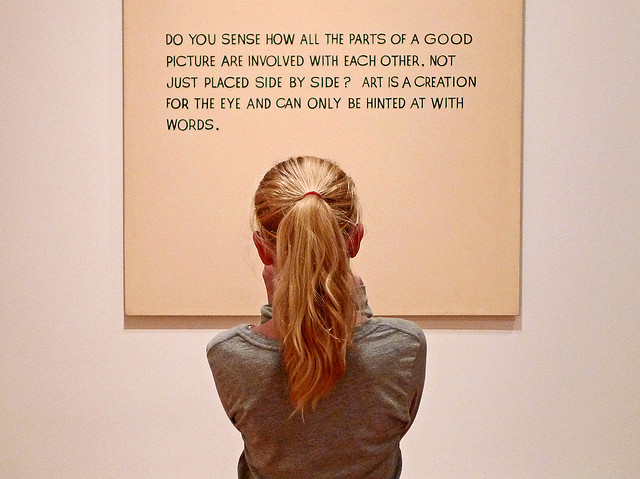

Image by an untrained eye

|

There are, of course, many other pressing arguments for the importance of photography literacy. I have been teaching photography for over 10 years. I was trained as an English teacher and came to photography with a background in art history and an amateur passion for taking photographs. I have taught photography in the context of a BTEC media course and as a GCSE and A level. Each context has affected the emphasis in my pedagogy so that I have taught photography as a vocational discipline (with a focus on documentary and commercial practice) and as a form of visual art (with a focus on creative expression). In recent months I have been thinking hard about my pedagogy and the affordances provided by the GCSE and A level photography courses for students at my school.

I have asked myself the following questions:

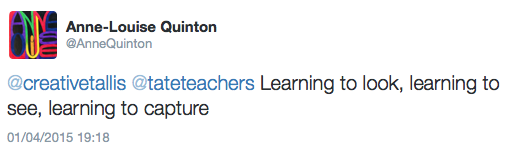

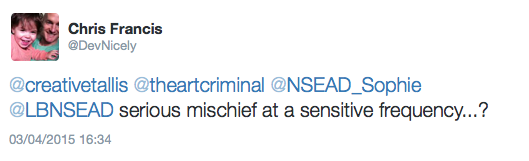

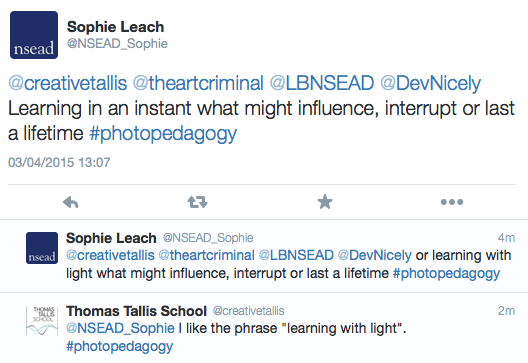

I have taken advantage of various social networks to consult colleagues about their #photopedagogy. Here are some of the responses I received:

I have asked myself the following questions:

- What are the threshold concepts that might enable students to develop a secure understanding of photography?

- What is the right balance between knowing that and knowing how to in photography?

- How much knowledge of photography history is desirable so that students are able to contextualise their own creative products?

- How much knowledge of technical processes and understanding of photographic technology is important, especially processes that are rapidly becoming expensive and obsolete?

I have taken advantage of various social networks to consult colleagues about their #photopedagogy. Here are some of the responses I received:

I think I teach photography as therapy as a way to explore identity. As you know I work in a behaviour unit. Exploring an image as personal to the taker is important to me, you have to have a personal connection with your photographs otherwise it's just an image. My students had so much fun with the toy project I did with them and it really gave me an insight into their imaginations. Somehow it helped them get back to their childhood or how it should have been, even if some of the work they produced was quite disturbing! They would have been happy to carry on with that project all year! Jo Spence, Richard Billingham, Sonia Boyce & Ingrid Pollard are really important photographers to me in relation to phototherapy and why people make images. I would love to retrain as a photo-therapist one day..... Frances Akinde

You cannot teach photography without reference to its history and an experience of traditional film-based practice. It's the advent of digital which has led to a lack of understanding, even interest in, the basic photographic techniques. "I just hope for the best and delete the shots I don't like." John McCann

Each of these perspectives raises really vital issues about the nature of photography pedagogy. Frances describes the therapeutic qualities of the medium and its ability to give shape to the personal imagination. Anne-Louise identifies the capacity of photography to explore the crucial difference between looking and seeing. John reminds us of the ground work that should be done with photography students, the explicit teaching of traditional processes so that they are able to understand the historical context for their (mostly) digital practice. Sophie's tweets identify two key concepts for photography: time and light and she reminds us of photography's disruptive power. I particularly like her phrase "learning with light" as a summary for all photography pedagogy. Chris draws attention to the creative potential for photography and its ability to challenge conventions in his notion of "serious mischief", not to mention the fun that comes with experimentation and divergent thinking. Susan's tweet emphasises the responsibility to create and analyse the power of photographic images so that their meanings can be understood by artists and viewers alike.

This diversity of views about photography pedagogy is, in my view, a real strength of the subject. What concerns me is that photography teachers may find themselves fairly marginalised in schools and colleges and unable to debate these issues with colleagues. I am not surprised that new photography courses seem to be springing up across the country. After all, young people have an unprecedented access to photographic technology particularly with the advent of high resolution camera phones and a growing marketplace of mobile apps. Organisations like the NSEAD and wonderful teachers like Susan Coles are busy nurturing the development of colleagues new to photography teaching. Those of us who have our courses available for perusal online receive regular emails from teachers asking for support. There is a tremendous demand for ideas and information about photography teaching. I very much hope that colleagues across the country can collaborate more effectively so that we may all benefit from the wealth of experience and expertise in the photography teacher community.

Of course, a key resource in the development of a successful photography pedagogy is our students. This year I have been conducting an action research project with the help of my Year 12 photography group. The aim of the project has been to explore whether the explicit teaching of key Threshold Concepts in photography can support them in developing their critical understanding. I have written about the development of these concepts in a separate article and I am very grateful to the colleagues who helped me refine and develop them. They are very much a first draft and I am keen to keep revisiting them to make them as useful as possible. Part of my research alongside the students has involved conducting a series of interviews with them about the course, what they feel they have learned, what they have found challenging and what they hope to learn in the near future. Their responses have helped me reflect on the curriculum in Year 12 specifically and have provided a useful corrective for my assumptions and prejudices about the affordances of the course.

For example, they had some interesting views about the relationship between knowing that (declarative knowledge) and knowing how to (procedural knowledge). They valued the emphasis placed on personal problem solving and individualised outcomes but they expressed a strong desire to know more about how their cameras worked. They were unsure about needing to know more about photography history, especially if this came in the form of whole class lectures, but they were keen to know more about a wider range of historical and contemporary artists. They felt most challenged by the quality of their own ideas and wanted to know how to develop more and have confidence in them. Based on this feedback I intend to make some changes to the A level course this year, ready for next year's cohort.

This diversity of views about photography pedagogy is, in my view, a real strength of the subject. What concerns me is that photography teachers may find themselves fairly marginalised in schools and colleges and unable to debate these issues with colleagues. I am not surprised that new photography courses seem to be springing up across the country. After all, young people have an unprecedented access to photographic technology particularly with the advent of high resolution camera phones and a growing marketplace of mobile apps. Organisations like the NSEAD and wonderful teachers like Susan Coles are busy nurturing the development of colleagues new to photography teaching. Those of us who have our courses available for perusal online receive regular emails from teachers asking for support. There is a tremendous demand for ideas and information about photography teaching. I very much hope that colleagues across the country can collaborate more effectively so that we may all benefit from the wealth of experience and expertise in the photography teacher community.

Of course, a key resource in the development of a successful photography pedagogy is our students. This year I have been conducting an action research project with the help of my Year 12 photography group. The aim of the project has been to explore whether the explicit teaching of key Threshold Concepts in photography can support them in developing their critical understanding. I have written about the development of these concepts in a separate article and I am very grateful to the colleagues who helped me refine and develop them. They are very much a first draft and I am keen to keep revisiting them to make them as useful as possible. Part of my research alongside the students has involved conducting a series of interviews with them about the course, what they feel they have learned, what they have found challenging and what they hope to learn in the near future. Their responses have helped me reflect on the curriculum in Year 12 specifically and have provided a useful corrective for my assumptions and prejudices about the affordances of the course.

For example, they had some interesting views about the relationship between knowing that (declarative knowledge) and knowing how to (procedural knowledge). They valued the emphasis placed on personal problem solving and individualised outcomes but they expressed a strong desire to know more about how their cameras worked. They were unsure about needing to know more about photography history, especially if this came in the form of whole class lectures, but they were keen to know more about a wider range of historical and contemporary artists. They felt most challenged by the quality of their own ideas and wanted to know how to develop more and have confidence in them. Based on this feedback I intend to make some changes to the A level course this year, ready for next year's cohort.

|

For the teacher new to the subject, there are wide range of great texts that can help you get to grips with the theoretical, historical and practical aspects of the subject. One of my favourites is 30 Second Photography edited by Brian Dilg. The introduction quotes Philip-Lorca DiCorcia's comment that:

Photography is a foreign language everyone thinks he speaks. Dilg reminds us that trillions of photographs are now taken annually. Billions of people might be considered to be amateur photographers and yet the discipline of photography is arguably as little understood today as it has ever been. Rather than make photography more intelligible, the digital revolution may have further confused it. Developing a pedagogy that aims to demystify photography so that students develop a clear understanding of its Threshold Concepts is, for me now, an important project.

JN April 2015 |