Words & Pictures

By Katherine Leedale

I’m a photographer, visual artist, and workshop facilitator who cannot stay away from words. I’d like to share a project I helped run with young people earlier in the year, as well as some general reflections on the interaction between writing and photography.

From a sprawling clan of teachers, books and words were the highly valued items in my family in the same way as records and music might be in another. I read voraciously growing up, vanishing for long hours into other worlds conjured by the stark and apparently simple shapes of letters on a page. It felt natural to study English Literature at university, after which I developed a photography practice, returned to study, and begin working in the field (primarily documenting for theatres and arts organisations). Only in more recent years have I pursued an artistic practice and so had this inability to separate the linguistic and visual interests highlighted again and again.

When I look at a photograph, I am narrating it to myself, almost in full sentences, as a way of identifying content, contemplating form, technique, impulse, meaning. When I read (novels and short stories mostly, with some poetry) I want writing that is rich in sensual detail that allows me to build a strongly defined mental image and then inhabit it. Reading and photographing, for me, complement - or confuse - illuminate - or complicate - one another. A recent residency in Iceland resulted in a book where I manfully resisted the insertion of any text save a title and a colophon and it felt like a major effort. It was therefore necessary to also create a quick, ‘zine-type edition of assembled poems and to pull together a letter-writing project I plan to turn into a self-published magazine, where I will try my hardest not to include any photographs. For the most part though I’ve accepted the need to engage with both expressions and now regularly digitally inscribe on my images, turn them into books that do contain text, and collaborate with writers.

It stems in part from the philosophy of photography I’ve had to develop since I’ve begun facilitating workshops - had to in order to understand what I want the participants (students in schools, families in museums, service users of charities) to take away from my sessions. Many of these overlap with the threshold concepts outlined on this site - though I didn’t know that when I wrote them down ahead of a teacher’s CPD session!

The storytelling is the key issue for me - the imposition of a narrative on the part of the viewer feels to me like an inescapable part of any art form and one that the artist cannot help but engage with, whether that’s to deliberately twist or play with it, or to utilise their making to point the viewer towards a particular understanding. The fact is that neither images nor writing can ever tell the whole story of anything - but that sometimes one can help the other along. Using both in a project becomes a testing ground for the strengths and weaknesses of either form and can result in some thought-provoking activities for students that enable them to really chew on the big questions about photography.

When the Museum of London contacted me to ask if I could run some sessions with young people at an Arabic supplementary school in Neasden, tied to the museum’s Suffragette exhibition, I had the chance to design a set of sessions around my interest in making a palimpsest of writing/s (particularly handwriting) and image-creation. Students varied in age and are from different cultural and religious backgrounds but all brought together to study spoken and written Arabic each weekend.

The Museum, as always, was really open to hearing ideas from me about how to connect the students with the content of their exhibition, and issued me with the germ of the idea by asking if we could look at protest imagery. Therefore I began by tracing a thread from archival photography of the Suffragettes protesting. We looked at these in conjunction with screenshots of Google Image searches I’d performed for modern-day marches from all corners of the globe (I wanted to emphasise the universal nature of the need to march). Once gathered together en masse, the students duly noted the presence in every single image of placards or banners covered in slogans; sashes worn by women in the 1910s being echoed in the pun-tastic, be-glittered efforts of the anti-Trump crowds in 2017. We talked about why the protestors felt the need to express themselves in language and about the blunt, punchy nature of the statements they chose to make.

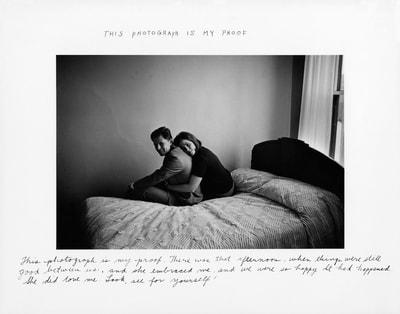

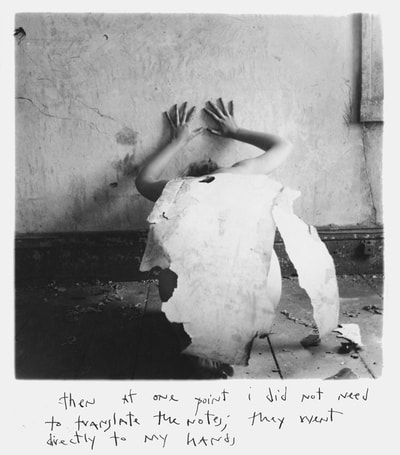

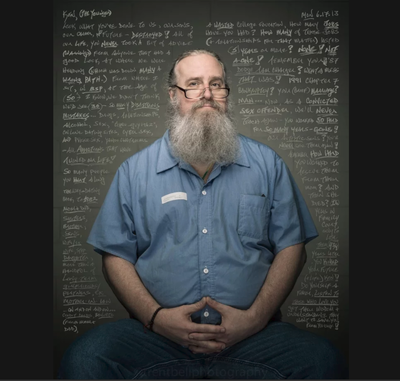

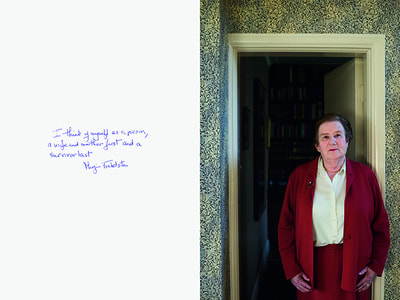

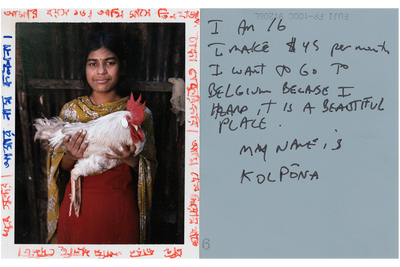

From here we moved to examining the work of artists working with both text, specifically handwritten, and photographs - Jim Goldberg’s Sharpie-d Polaroids, Trent Bell’s portraits of prison inmates with handwritten letters to their younger selves, Harry Borden’s meditative series of Holocaust survivors, and Ben Pease’s reappropriated archival images of First Nations Americans. The students responded sensitively and drew astute connections between this more artistic, considered work, and the photojournalistic snaps I’d shown them earlier - reaching the conclusion, as I hoped they would, that the handwritten statement carries a personal weight and a testimonial heft that isn’t matched by typed text.

From a sprawling clan of teachers, books and words were the highly valued items in my family in the same way as records and music might be in another. I read voraciously growing up, vanishing for long hours into other worlds conjured by the stark and apparently simple shapes of letters on a page. It felt natural to study English Literature at university, after which I developed a photography practice, returned to study, and begin working in the field (primarily documenting for theatres and arts organisations). Only in more recent years have I pursued an artistic practice and so had this inability to separate the linguistic and visual interests highlighted again and again.

When I look at a photograph, I am narrating it to myself, almost in full sentences, as a way of identifying content, contemplating form, technique, impulse, meaning. When I read (novels and short stories mostly, with some poetry) I want writing that is rich in sensual detail that allows me to build a strongly defined mental image and then inhabit it. Reading and photographing, for me, complement - or confuse - illuminate - or complicate - one another. A recent residency in Iceland resulted in a book where I manfully resisted the insertion of any text save a title and a colophon and it felt like a major effort. It was therefore necessary to also create a quick, ‘zine-type edition of assembled poems and to pull together a letter-writing project I plan to turn into a self-published magazine, where I will try my hardest not to include any photographs. For the most part though I’ve accepted the need to engage with both expressions and now regularly digitally inscribe on my images, turn them into books that do contain text, and collaborate with writers.

It stems in part from the philosophy of photography I’ve had to develop since I’ve begun facilitating workshops - had to in order to understand what I want the participants (students in schools, families in museums, service users of charities) to take away from my sessions. Many of these overlap with the threshold concepts outlined on this site - though I didn’t know that when I wrote them down ahead of a teacher’s CPD session!

- The photograph is a memory.

- Photographing is a form of mindfulness.

- Looking becomes seeing through the act of focusing.

- Photography is not ‘pure’.

- Photographers are storytellers.

- Tools matter less than process and outcome.

The storytelling is the key issue for me - the imposition of a narrative on the part of the viewer feels to me like an inescapable part of any art form and one that the artist cannot help but engage with, whether that’s to deliberately twist or play with it, or to utilise their making to point the viewer towards a particular understanding. The fact is that neither images nor writing can ever tell the whole story of anything - but that sometimes one can help the other along. Using both in a project becomes a testing ground for the strengths and weaknesses of either form and can result in some thought-provoking activities for students that enable them to really chew on the big questions about photography.

When the Museum of London contacted me to ask if I could run some sessions with young people at an Arabic supplementary school in Neasden, tied to the museum’s Suffragette exhibition, I had the chance to design a set of sessions around my interest in making a palimpsest of writing/s (particularly handwriting) and image-creation. Students varied in age and are from different cultural and religious backgrounds but all brought together to study spoken and written Arabic each weekend.

The Museum, as always, was really open to hearing ideas from me about how to connect the students with the content of their exhibition, and issued me with the germ of the idea by asking if we could look at protest imagery. Therefore I began by tracing a thread from archival photography of the Suffragettes protesting. We looked at these in conjunction with screenshots of Google Image searches I’d performed for modern-day marches from all corners of the globe (I wanted to emphasise the universal nature of the need to march). Once gathered together en masse, the students duly noted the presence in every single image of placards or banners covered in slogans; sashes worn by women in the 1910s being echoed in the pun-tastic, be-glittered efforts of the anti-Trump crowds in 2017. We talked about why the protestors felt the need to express themselves in language and about the blunt, punchy nature of the statements they chose to make.

From here we moved to examining the work of artists working with both text, specifically handwritten, and photographs - Jim Goldberg’s Sharpie-d Polaroids, Trent Bell’s portraits of prison inmates with handwritten letters to their younger selves, Harry Borden’s meditative series of Holocaust survivors, and Ben Pease’s reappropriated archival images of First Nations Americans. The students responded sensitively and drew astute connections between this more artistic, considered work, and the photojournalistic snaps I’d shown them earlier - reaching the conclusion, as I hoped they would, that the handwritten statement carries a personal weight and a testimonial heft that isn’t matched by typed text.

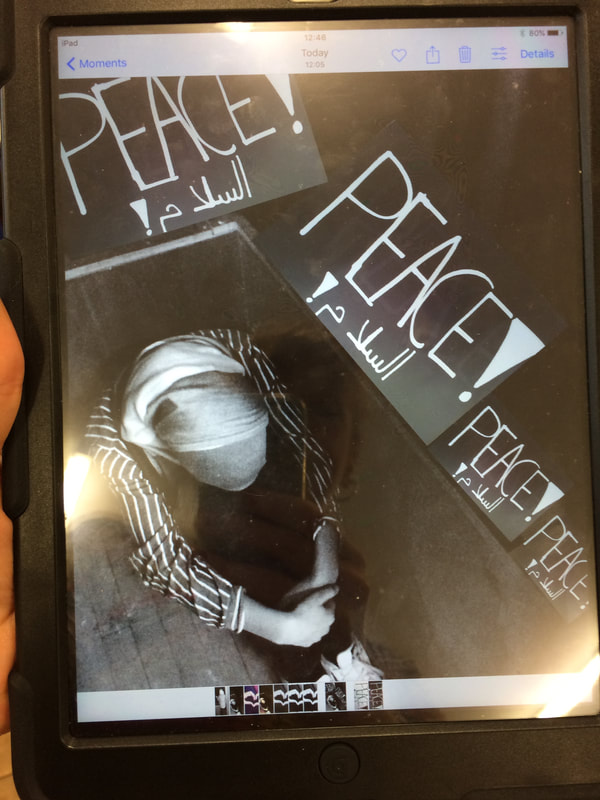

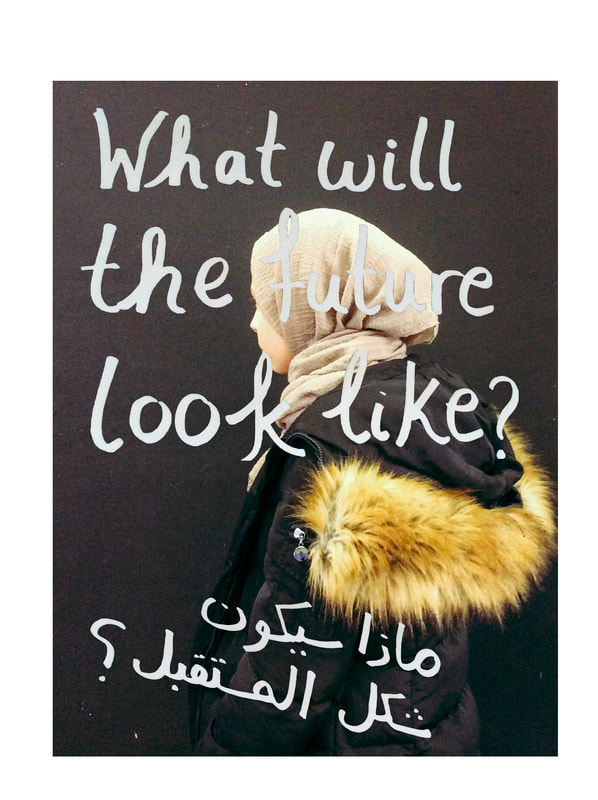

At this point I revealed that we’d be making our own versions of these layered images - but ones from the very personal perspective of the students. I wanted them to think about what they would put into the world as their protest statement - what opinion, concern, hope would they own with their writing, and image of themselves? Some students were more camera-shy than others, so we also had the opportunity to discuss how ‘portraiture’ doesn’t have to mean ‘an image of someone’s face’. After a quick session on photographing with iPads (the photographic tools available from the Museum, and one of my preferred options for workshop sessions), the young people helped to photograph one another before selecting an image apiece to represent themselves.

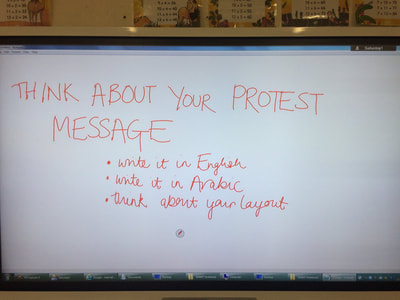

A long, strong first session! I sent them away with the task to think about their written statements and to write them out in both English and Arabic (to connect the work we were doing more closely to the remit of the school).

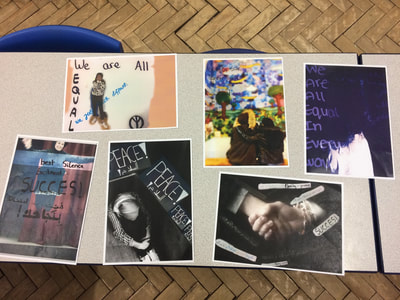

In the second session I introduced Photoshop Mix - a great app for iPad and other tablets that enables users to relatively easily create multi-layered images, collages and other digital cut-outs. It’s one I use in my own work and I like it for its simplicity and easy layout. I will say that covering the basics of it in one session with time for making too was an ambitious task - one that the students rose to admirably but not one I’m sure I’d recommend! They photographed their written statements and then they were off, experimenting with blend modes, filters, and ‘cutting out’ sections to create their final image. The digital nature of this collaging felt less risky, less fixed than asking students to write on print-outs and also allowed some participants to create a more visually harmonious image by filtering both the image of their statement and the photograph of themselves. Another useful app is ‘Color Camera’ - which easily flips digital snaps into negative - so when layering against a dark background the text can be white (not something achievable within Mix). We also used my personal favourite editing app - Pixlr - with its myriad of effects, filters and adjustment tools (some more pleasing than others but with plenty of choice for individuals to stamp a look on their work).

A tip with using Mix - you don’t have to sign up for a (free) Creative Cloud account to use it, but I would recommend you do. This will allow students’ creations to be stored in the cloud as they go - as sometimes (particularly on older models) the app has a tendency to crash and this minimises the potential for progress to be lost.

At the end of this second session each student had completed one layered and / or collaged image that they were happy with. Post-session I then prepared the images for print by resizing them (the file can be downloaded from the cloud straight into Photoshop as a layered file). The Museum had them printed handsomely at about A2 size and mounted on foamboard. The students were participating in the Arts Award programme and this enabled them to display and present their work at the Museum itself during a Festival weekend. Rightly so, they were proud of what they’d created, and the physical quality of the final outcomes was very high. The students were bright, creative, hardworking and inquisitive and the project generated conversations about everything from the value of aesthetics in my personal artistic practice to the place of women in global societies now compared to a century ago. Completing their Arts Award proof sketchbooks in the weeks afterwards enabled us to reflect on what they’d gained from the experience, and a couple of the students told me they’d downloaded the apps we’d used so they could carry on working with them at home.

A long, strong first session! I sent them away with the task to think about their written statements and to write them out in both English and Arabic (to connect the work we were doing more closely to the remit of the school).

In the second session I introduced Photoshop Mix - a great app for iPad and other tablets that enables users to relatively easily create multi-layered images, collages and other digital cut-outs. It’s one I use in my own work and I like it for its simplicity and easy layout. I will say that covering the basics of it in one session with time for making too was an ambitious task - one that the students rose to admirably but not one I’m sure I’d recommend! They photographed their written statements and then they were off, experimenting with blend modes, filters, and ‘cutting out’ sections to create their final image. The digital nature of this collaging felt less risky, less fixed than asking students to write on print-outs and also allowed some participants to create a more visually harmonious image by filtering both the image of their statement and the photograph of themselves. Another useful app is ‘Color Camera’ - which easily flips digital snaps into negative - so when layering against a dark background the text can be white (not something achievable within Mix). We also used my personal favourite editing app - Pixlr - with its myriad of effects, filters and adjustment tools (some more pleasing than others but with plenty of choice for individuals to stamp a look on their work).

A tip with using Mix - you don’t have to sign up for a (free) Creative Cloud account to use it, but I would recommend you do. This will allow students’ creations to be stored in the cloud as they go - as sometimes (particularly on older models) the app has a tendency to crash and this minimises the potential for progress to be lost.

At the end of this second session each student had completed one layered and / or collaged image that they were happy with. Post-session I then prepared the images for print by resizing them (the file can be downloaded from the cloud straight into Photoshop as a layered file). The Museum had them printed handsomely at about A2 size and mounted on foamboard. The students were participating in the Arts Award programme and this enabled them to display and present their work at the Museum itself during a Festival weekend. Rightly so, they were proud of what they’d created, and the physical quality of the final outcomes was very high. The students were bright, creative, hardworking and inquisitive and the project generated conversations about everything from the value of aesthetics in my personal artistic practice to the place of women in global societies now compared to a century ago. Completing their Arts Award proof sketchbooks in the weeks afterwards enabled us to reflect on what they’d gained from the experience, and a couple of the students told me they’d downloaded the apps we’d used so they could carry on working with them at home.

Having run these sessions with this group, I was keen to find other ways of introducing the endless interactions of words and pictures and drew myself up a wishlist of activities:

Places to look for inspiration might include:

I haven’t had a chance to trial these yet, but if you do I’d love to hear how they work for you. There’s remarkably little creative writing about photography - almost no poems and I can’t think of many characters in novels who tackle the form - so again, if you know of others please let me know.

The ‘London Nights’ photography exhibition is running at the Museum until 11 November 2018.

www.museumoflondon.org.uk/schools

www.katherineleedale.com

instagram.com/kleedale

- Investigating the concrete properties of photograph and poem as stimulus to make new work. Write a haiku about a casual snapshot or a 400 line epic about a handcrafted Ansel Adams print. Or vice versa.

- Filling a 6x4 piece of paper with a textual description of a 6x4 photograph (other sizes are available…)

- Finding the creative writing club or class in your school or learning environment and set up a consequences-style exchange of forms. Or a ping-pong back and forth.

- Make a piece of writing utilising photographs of words found in the street. An extra challenge would be to only use them in the order of capture.

Places to look for inspiration might include:

- Reading Howard Nemerov and seeing whether there is any connection with his sister Diane Arbus’ work…

- Taking a closer look at Lee Miller through the poet Jacqueline Saphra’s collection A Bargain with the Light (caution: contains examination of some of the more troubling images of Miller captured by her father).

- Signing up for or submitting to the Visual Verse online anthology.

- Talking about ekphrasis and whether you can reverse engineer an ekphrastic photograph from a piece of writing. What are the hooks that can be translated from page to print (or screen)?

I haven’t had a chance to trial these yet, but if you do I’d love to hear how they work for you. There’s remarkably little creative writing about photography - almost no poems and I can’t think of many characters in novels who tackle the form - so again, if you know of others please let me know.

The ‘London Nights’ photography exhibition is running at the Museum until 11 November 2018.

www.museumoflondon.org.uk/schools

www.katherineleedale.com

instagram.com/kleedale