Post 16 lesson plan:

What is photopoetry? An exploration of the symbiotic relationship between poetry and photography.

By Jon Nicholls, Thomas Tallis School and Kate Ling, The John Roan School

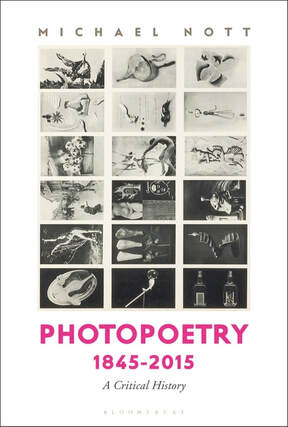

This resource is designed to explore the relationship between poems and photographs in the form of photopoetry publications and is an off-shoot from a related resource on the photobook. It is intended for teachers and students interested in the potential of an inter-disciplinary (possibly collaborative) project uniting words and pictures. Words are often used to anchor the meanings of photographs and we deal with issues related to the contexts in which photographs are viewed in Threshold Concepts #7. We are indebted to Michael Nott's ground-breaking critical history of photopoetry and many other researchers and experts. We have identified a selection of these in the Additional Resources at the end. We would also like to thank Steven J. Fowler and David Solo for their invaluable support and expertise.

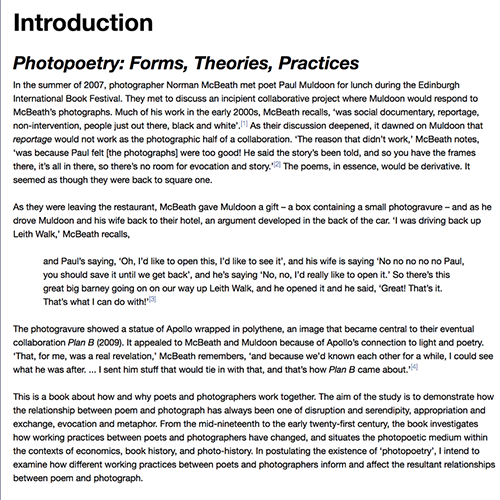

The term 'photopoetry' and its various alternatives - photopoème, photoetry, photoverse, photo-graffiti etc. - attempts to describe an art form in which the poetry and photography are equally important and, often, directly and symbiotically related. Michael Nott suggests that:

The term 'photopoetry' and its various alternatives - photopoème, photoetry, photoverse, photo-graffiti etc. - attempts to describe an art form in which the poetry and photography are equally important and, often, directly and symbiotically related. Michael Nott suggests that:

the relationship between poem and photograph has always been one of disruption and serendipity, appropriation and exchange, evocation and metaphor

|

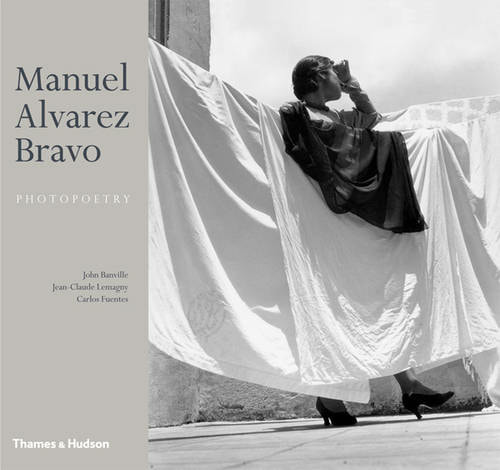

Photographs are often referred to as having 'poetic' qualities. A photograph and a poem may have similar qualities. In 1981, Italian photographer Luigi Ghirri produced a series of photographs of his hometown which he referred to as Smalltown Poetics. A recent (2008) retrospective anthology of Manual Alvarez Bravo's photographs is entitled Photopoetry. Neither includes poems. Jack Kerouac's famous introduction to Robert Frank's The Americans praises the photographer for having "sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film." An online interview with Canadian photographer Jeff Wall is titled Pictures Like Poems.

One might consider a particular attitude or way of perceiving the world as 'poetic': Poetry is a state of being, of attitude. It’s an exalted, ecstatic state of living, of seeing, of experiencing: [an] intense, intensified way of seeing, perceiving reality, both in art and living. There is poetry in literature, in cinema, in dance, in all of the arts. |

|

Or, as nineteenth century photographer P. H. Emerson thought:

The value of a picture is not proportionate to the trouble and expense it costs to obtain it, but to the poetry that it contains. These correspondences between photography and poetry are brought into sharp relief by photopoetry - specific examples of published collaborations between photographers and poets (sometimes the same person). Writer and artist S. J. Fowler describes the challenge of exploring photopoetry as follows:

To begin, we must ask ourselves what these mediums actually are, at heart, and then what they can be together? Finally, what is the purpose of their combination? What can they do together? And why is it relatively rare to see a cohesive combination of the two - with fidelity to poetry that isn’t just text, or discourse, or opinion, and photography that isn’t just pictorial? |

Sometimes, poets talk admiringly of photography, aspiring to its directness or regretting their ability to escape a 'snapshot' type of vision. Poets have also written beautifully about photographs, as in this example by Rilke:

|

What I want in poetry is a kind of abstract photography Of the nerves, but what I like in photography Is the poetry of literal pictures of the neighbourhood. -- John Koethe, from Pictures of Little Letters sometimes everything I write

with the threadbare art of my eye seems a snapshot, lurid, rapid, garish, grouped, heightened from life, yet paralysed by fact. -- Robert Lowell, from Epilogue |

In the eyes: dream. The brow as if it could feel

something far off. Around the lips, a great freshness — seductive, though there is no smile. Under the rows of ornamental braid on the slim Imperial officer’s uniform: the saber’s basket-hilt. Both hands stay folded upon it, going nowhere, calm and now almost invisible, as if they were the first to grasp the distance and dissolve. And all the rest so curtained with itself, so cloudy, that I cannot understand this figure as it fades into the background — . Oh quickly disappearing photograph in my more slowly disappearing hand. -- Rainer Maria Rilke, Portrait of My Father as a Young Man translated by Stephen Mitchell |

Poetry and photography are clearly distinct art forms. The history of poetry is much longer than that of photography. One makes pictures out of words, the other makes pictures out of light. Most photographs represent a fraction of the time contained in most poems. But how are poems and photographs similar? What unites poets and photographers?

The 'language' of one can be used as a metaphor for the 'language' of the other. Poems can be like 'snapshots'. Photographs can be 'lyrical'. Poems and photographs are both representations of something. Words and photographs are both special types of sign. If the written word is the 'image' of spoken language then the photograph is the 'image' of the visual subject. Poems and photographs could be said to have frames (this is especially true of shorter, single page poems which have a clear edge). They are both compressions, or abstractions, of reality. They both convey an experience of heightened perception, an intensity of looking/feeling. Poets and photographers perhaps share a common interest in transforming a lived experience into a memorable representation (a work of art?) They both enjoy collecting, organising, cataloguing, editing, arranging, sequencing, publishing, communicating. Works of photopoetry seek to connect poems and photographs whilst maintaining their distinctness.

Here is photographer Alec Soth discussing the relationship between photography, poetry and memory in his work:

The 'language' of one can be used as a metaphor for the 'language' of the other. Poems can be like 'snapshots'. Photographs can be 'lyrical'. Poems and photographs are both representations of something. Words and photographs are both special types of sign. If the written word is the 'image' of spoken language then the photograph is the 'image' of the visual subject. Poems and photographs could be said to have frames (this is especially true of shorter, single page poems which have a clear edge). They are both compressions, or abstractions, of reality. They both convey an experience of heightened perception, an intensity of looking/feeling. Poets and photographers perhaps share a common interest in transforming a lived experience into a memorable representation (a work of art?) They both enjoy collecting, organising, cataloguing, editing, arranging, sequencing, publishing, communicating. Works of photopoetry seek to connect poems and photographs whilst maintaining their distinctness.

Here is photographer Alec Soth discussing the relationship between photography, poetry and memory in his work:

|

Elsewhere, in reference to an album of photographs and poems by Rudolf Burckhardt and Edwin Denby, Soth has the following to say:

I've often said that photographs and poetry don't work together. It's a huge generalisation and not actually accurate but it sometimes makes me uncomfortable. And the reason is that they are like two positive forces that bounce off each other and for it to work, I think, it requires both the photography and the poetry to be simplified and more common. It often feels pretentious to have fancy photographs and fancy poetry together. What exactly is the source of this discomfort? Why are there relatively few examples of successful pairings of poems and photographs? What does Soth mean when he describes poems and photographs as "fancy" and why must they, for him, both be "simplified" in order not to "bounce off each other"? Is there a danger that particular kinds of photographs and poetry together might cancel one another out? Why put them together at all?

|

|

What does poetry bring to photography that prose, for example, does not? [...] Both are concerned with images: the visual immediacy of the photographic image against the unravelling, modifying, accumulating verbal images that emerge from the poem. In conjunction, such visual and verbal images blend, clash, contradict, embolden, evoke, and resist each other...

-- Michael Nott

Some initial questions:

- What are the similarities between photographs and poems? How do poets/photographers perceive and represent the world? What are the differences?

- In what sense could a photograph be described as 'poetic'? What might poets admire about the qualities of photographs?

- How might you begin to create one or more photopoems? Would you wish to collaborate with someone (a poet or photographer) or do you think you might tackle the poetry and photography yourself?

Threshold Concept #7The meanings of photographs are never fixed, are not contained solely within the photographs themselves and rely on a combination of the viewer's sensitivity, knowledge and understanding, and the specific context in which the image is seen.

Photographs are often accompanied by various kinds of text - titles, captions, articles etc. The text helps to anchor the image which, otherwise, would be multivalent - open to many possible meanings and interpretations. Photopoetry might be considered as a special example of this type of image/text composite. In photopoetry, the nature of the interplay between photographs and poems depends on various factors. For example:

|

A (very) brief history of photopoetry

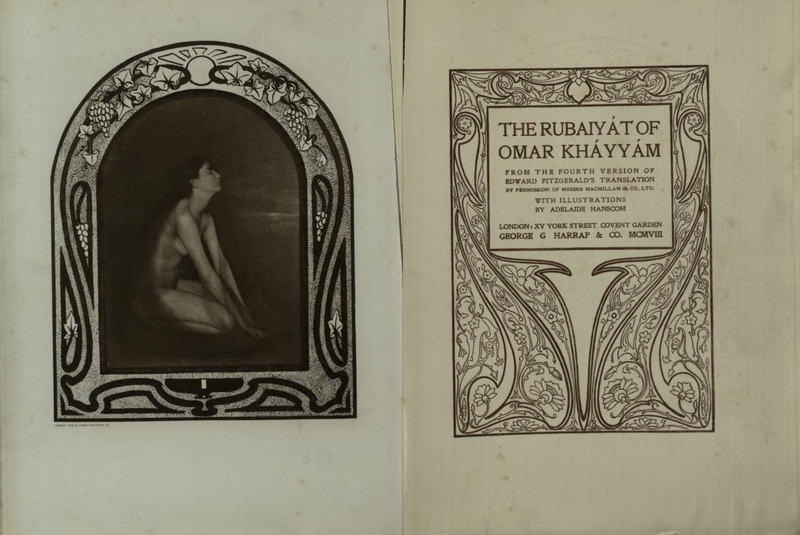

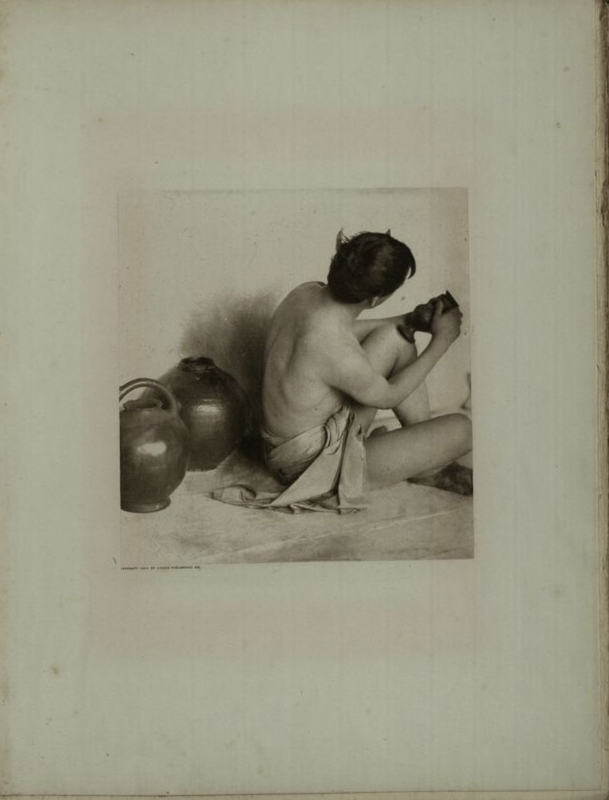

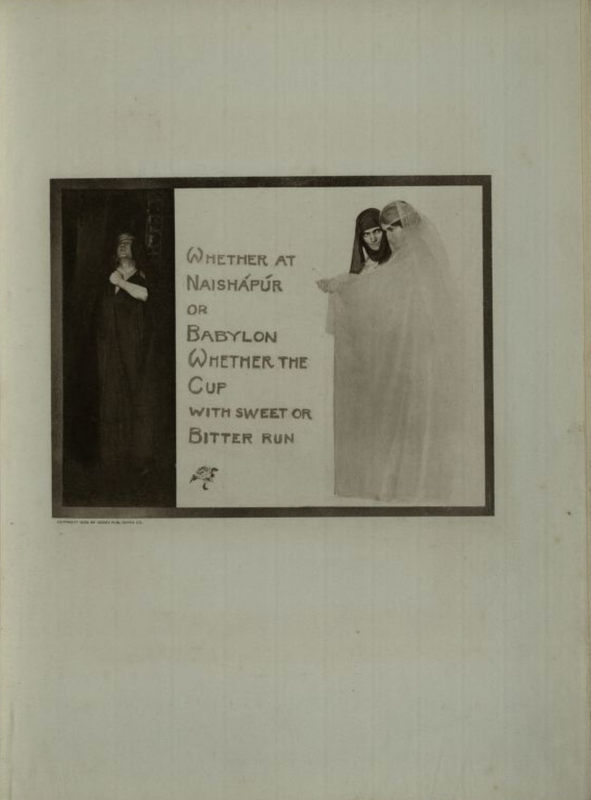

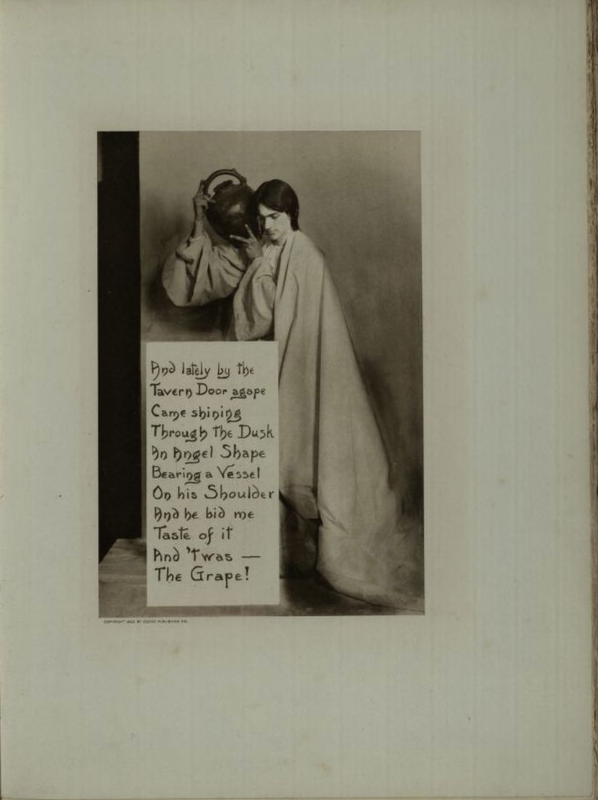

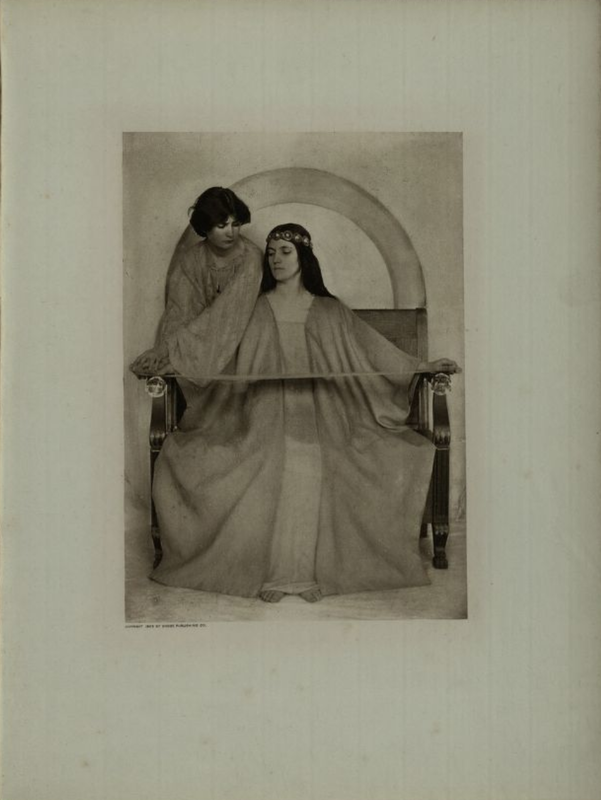

The first use of the term 'photopoem' can be found in Constance Phillips' Photopoems: A Group of Interpretations through Photographs (1936). The pairing of poems and photographs was not new but this is the first collection of such examples and helped to legitimise the phenomenon. Photopoetry publications were relatively popular throughout the Victorian period and became increasingly ambitious, moving from topographic and illustrative photographs to the more metaphorical use of the human figure. For example, Adelaide Hanscom Leeson’s Pictorialist photographs in the 1908 edition of FitzGerald’s Rubàiyàt of Omar Khayyàm.

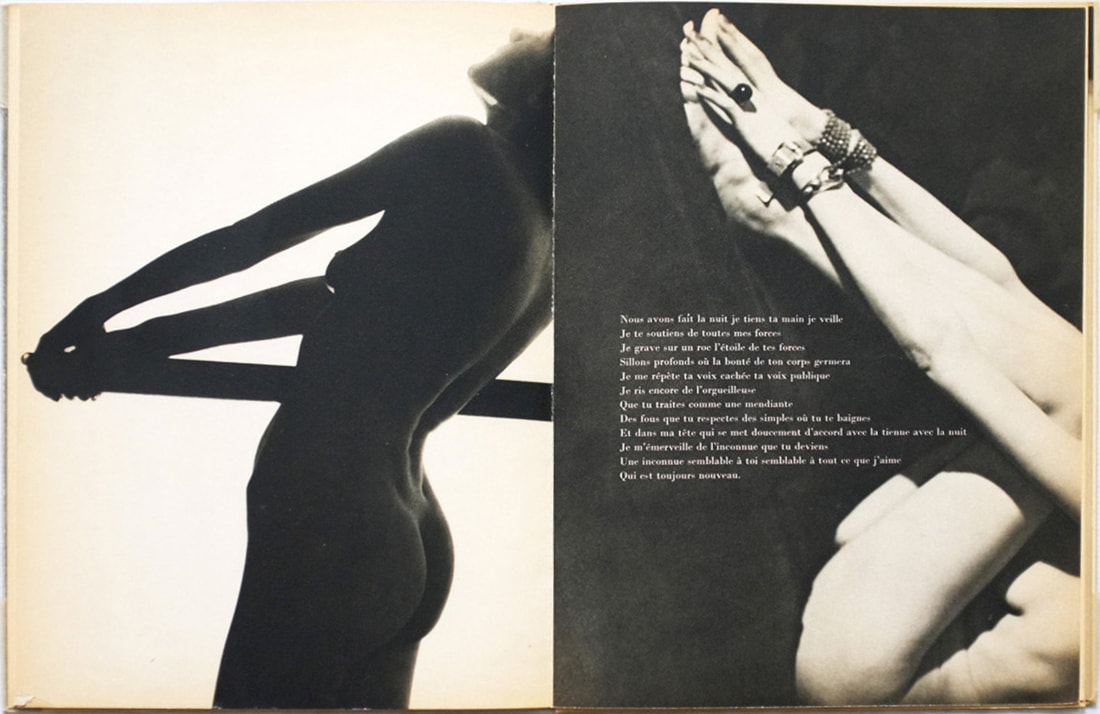

The relationship between poems and photographs was imaginatively explored by members of the avant-garde in the early 20th century. Perhaps the most famous example is a collaboration between Man Ray, Paul and Nusch Éluard entitled Facile (1935), a beautiful publication in which images and text create an integrated and unified design.

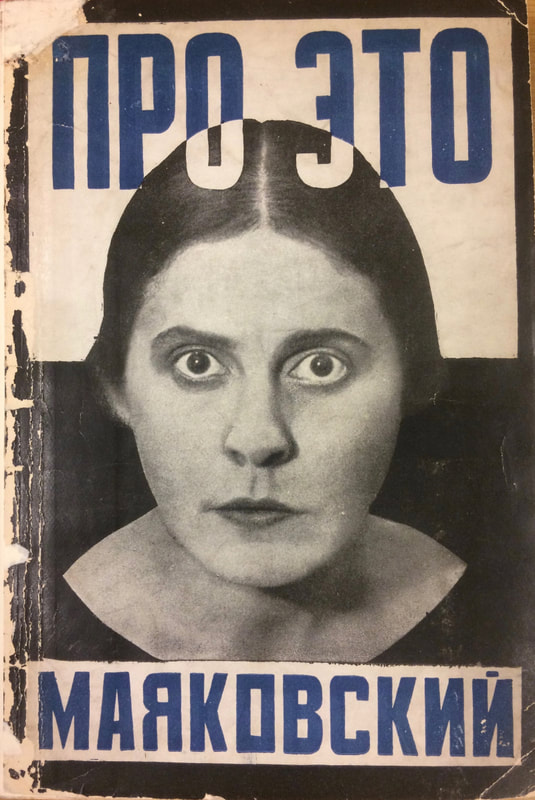

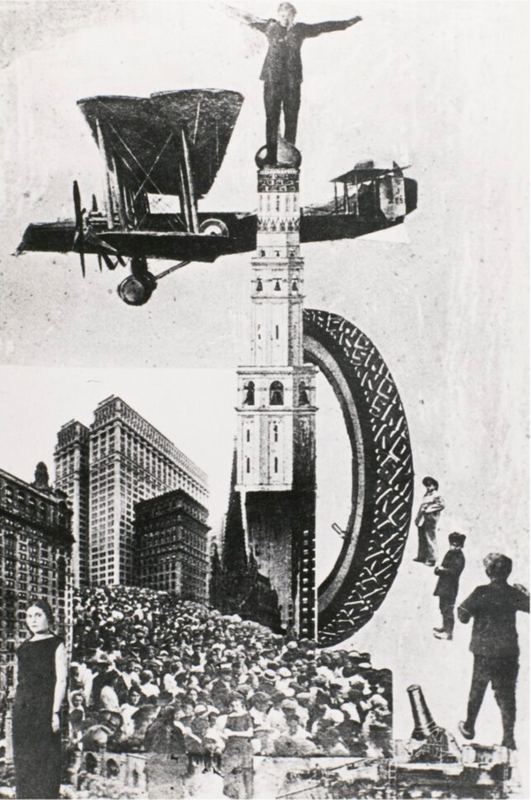

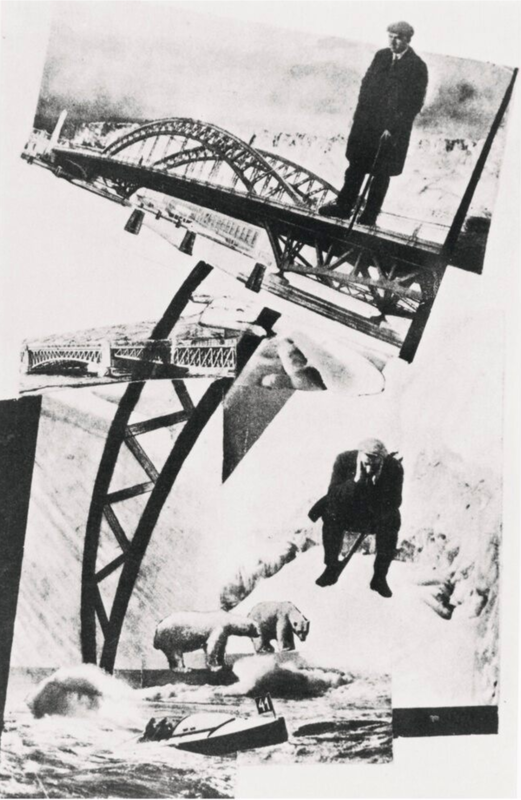

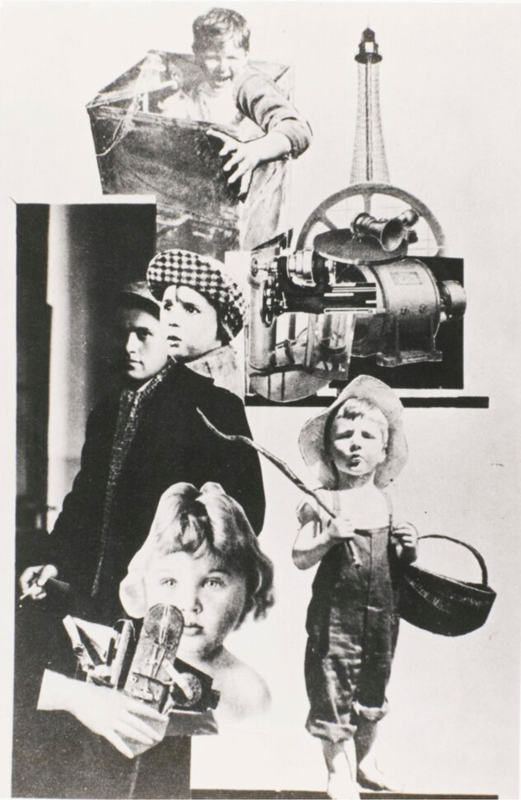

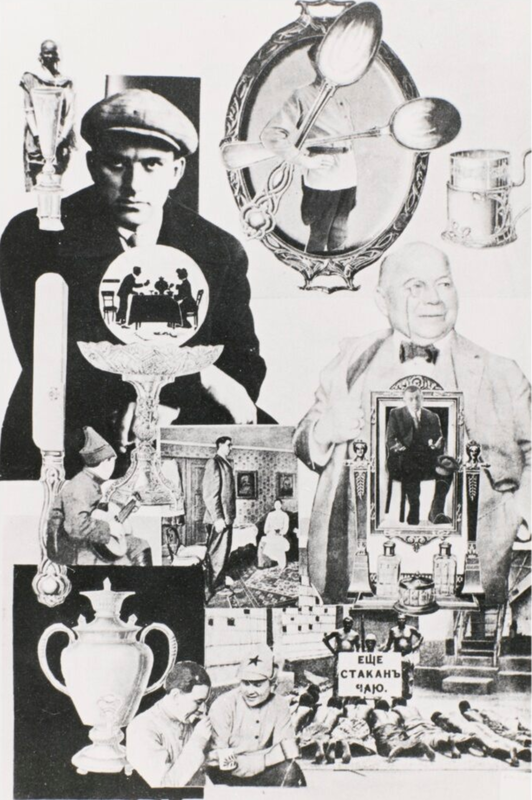

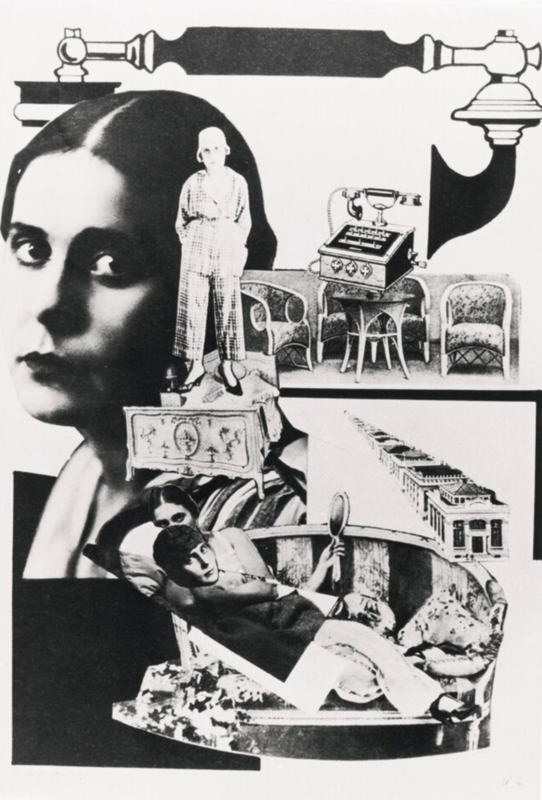

Another, and slightly earlier, example of this kind of modernist collaboration is Pro eto. Ei i mne (‘About This. To Her and to Me’) by poet Vladimir Mayakovsky and including a cover photograph and interior photomontages by Alexander Rodchenko.

|

The telephone, representing both separation and connection, is the central symbol of the first part of the poem. This clashing, technological imagery is reflected in the accompanying images:

Squeezing miraculously through the thin wire, stretching the rim of the mouthpiece funnel, a thunder of ringings bangs through the silence, then the telephone pours out its tinkling lava. A screaming, a ringing, shots slammed into the wall tried to blow it up. |

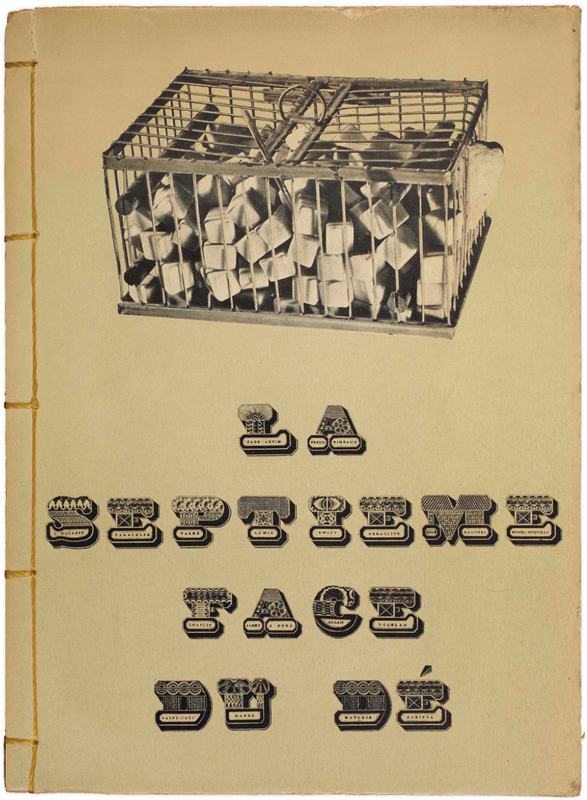

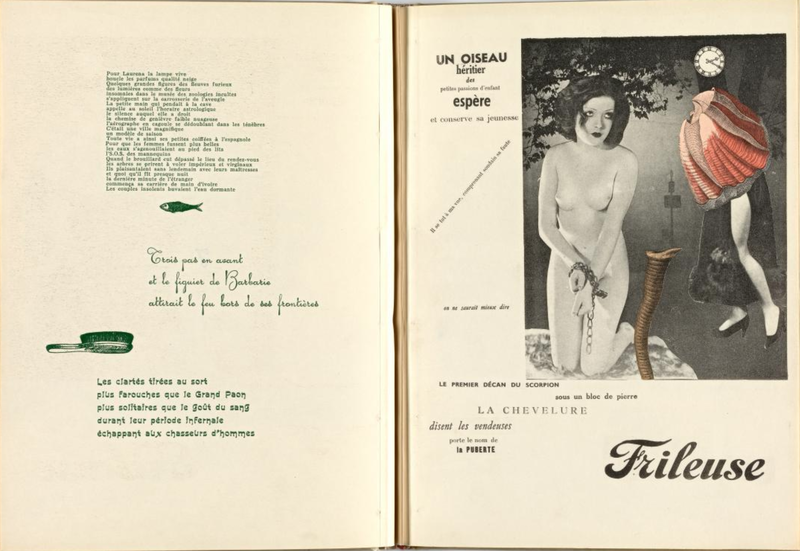

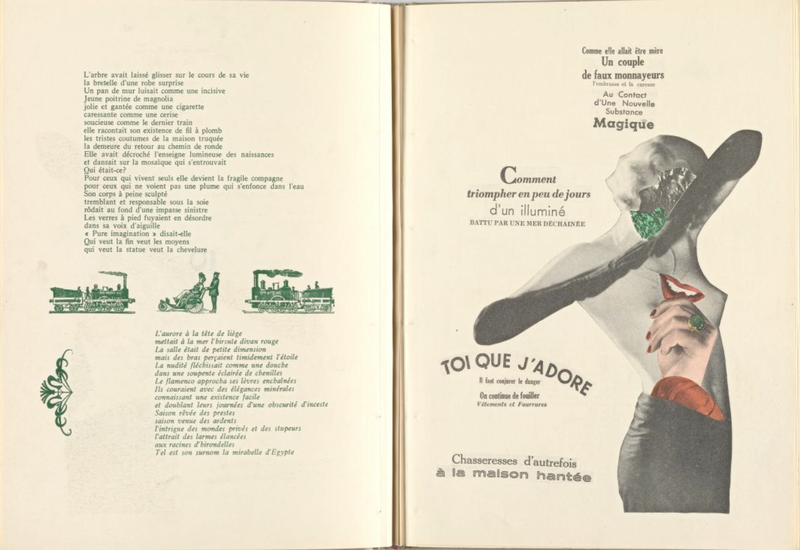

Adopting a similar interest in photomontage, George Hugnet's La septième face du dé (The seventh face of the die), published in 1936, combines the author's poems and photocollaged images in surreal juxtapositions.

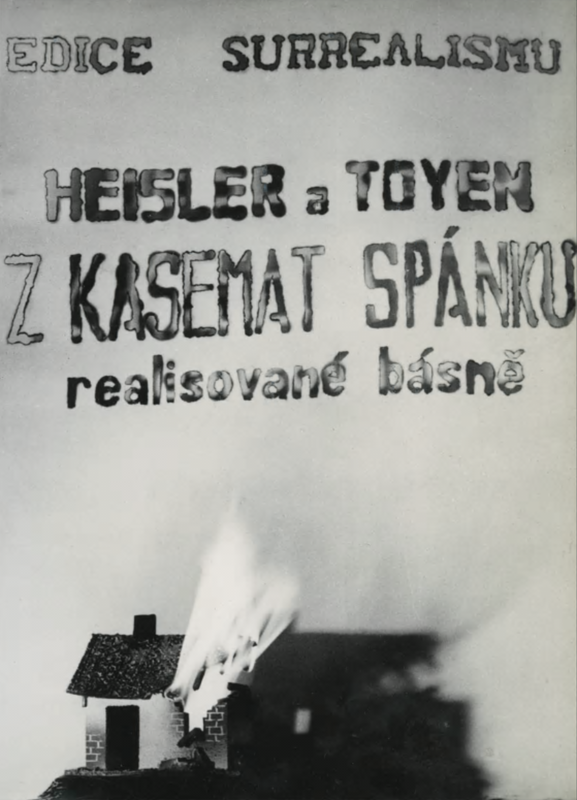

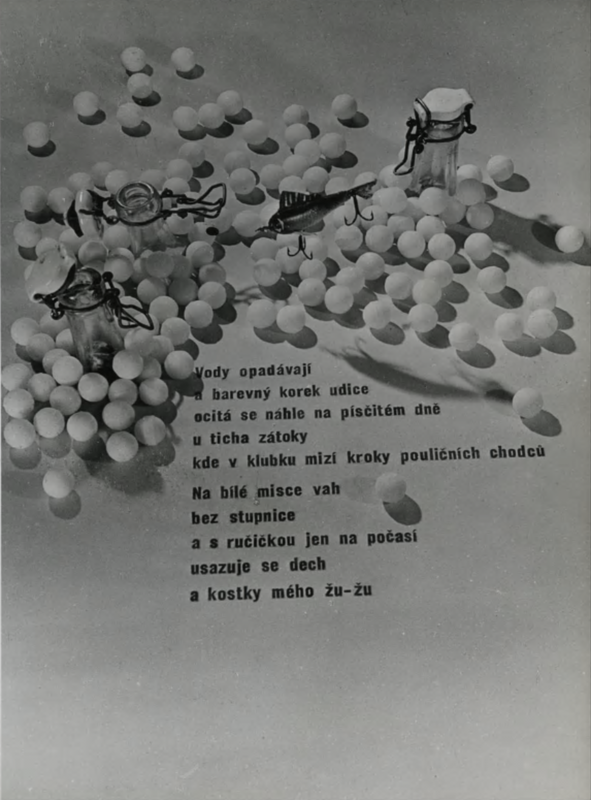

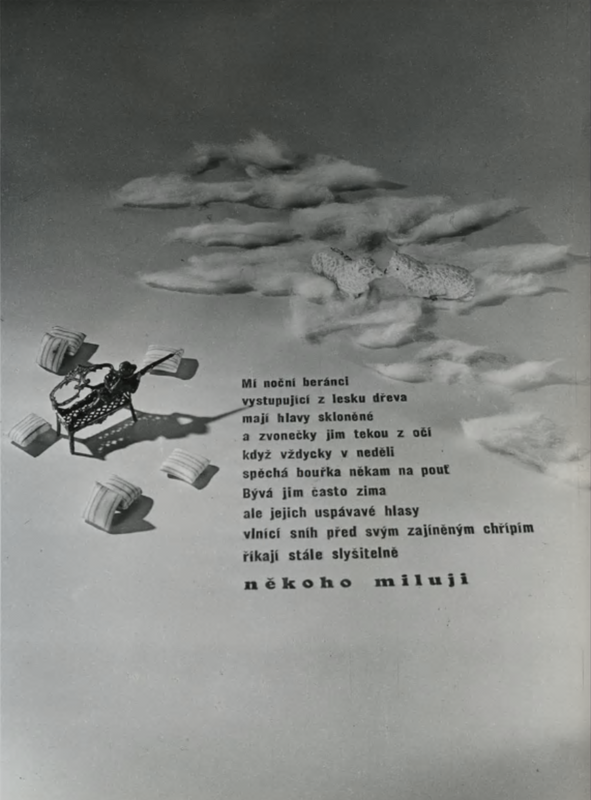

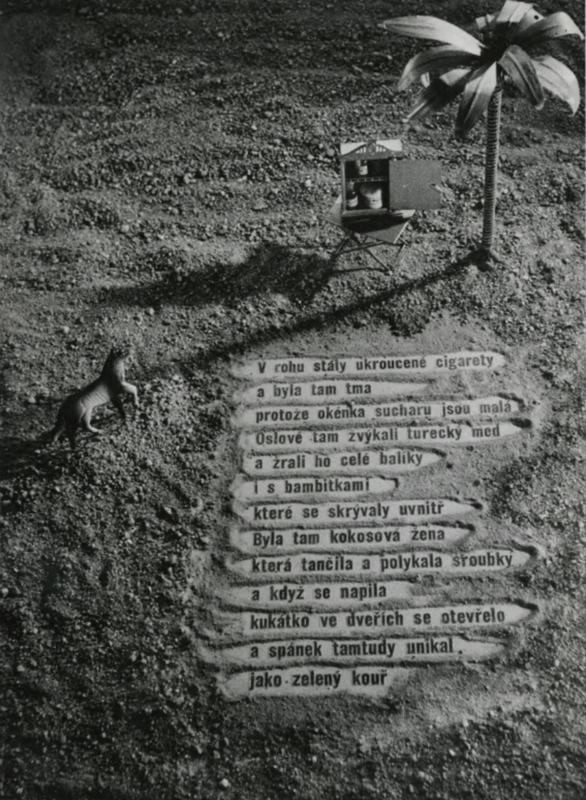

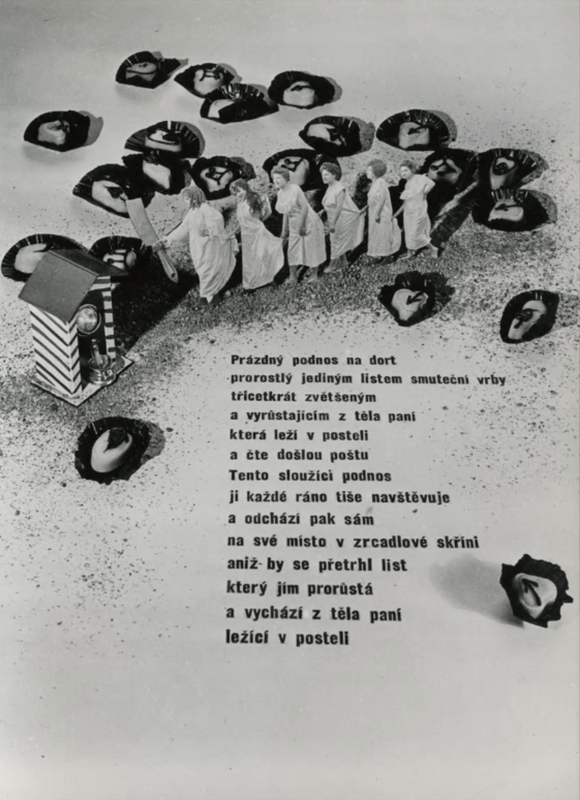

Another example of a Surrealist photopoetry publication is the remarkable From the Strongholds of Sleep: Materialised Poems (1940) by Czech artist Jindrich Heisler (in collaboration with fellow Surrealist, Toyen). Again, text and image are integrated visually so that they rely on one another for their meaning. It's no surprise that Surrealism, a movement founded by poets and dedicated to blurring the boundaries between different art forms, produced so many wonderful examples of photopoetry. It's also worth remembering that innovations in print technology, specifically the reproduction of photographs, helped to fuel an interest in combinations of text and image. Modernist photopoetry experiments demand greater imaginative work from the reader/viewer in piecing together disparate elements. These montages of text and image draw our attention to the act of reading/looking, what has been called 'montage thinking', and remind us that the reader/viewer is also a collaborator in the creation of meaning.

|

Photographs have often been made in response to poems written many years before. This was certainly the case for much of the early history of photopoetry.

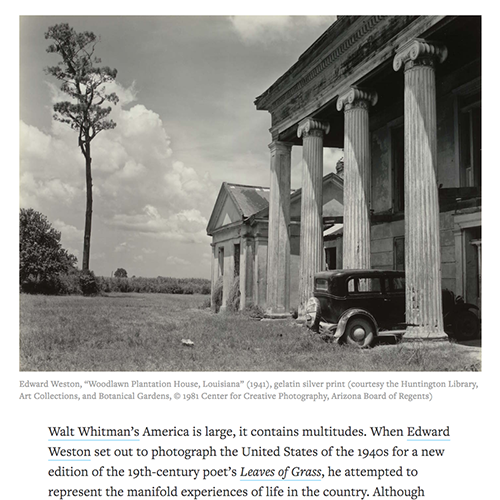

This film explores one example in which photographer Edward Weston created a set of images of America, at the beginning of WW2, to accompany a new edition of Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass. The relationship between poems and images in the final publication was deemed to be a failure but the project generated some beautiful photographs: |

|

Not all photopoetry experiments were intended to be seen by a large audience. For example, Rudolf Burckhardt and Edwin Danby's 'New York, N. Why?' originally constructed in 1938, was only published as a facsimile by Nazraeli Press in 2008. The combination of Burckhardt's urban photographs, carefully sequenced, and Denby's sonnets is sophisticated and witty. Arranged in three sections, we are presented with images of city surfaces, advertising signs and pedestrians in motion. Denby makes direct reference to his friend's photography:

This widening like a history mystery

Is what Rudi's camera takes in the city

and

Some place any one is someone anyday,

Which Rudi proves here clearly out of Euclid

The album is both playful and serious, ambitious and light-hearted. Clearly intended for the private amusement of a small coterie of friends and fellow artists, 'New York, N. Why?' explores some of the key issues associated with photopoetic texts; these concerns are played out in later examples of the genre but are arguably never quite resolved.

This widening like a history mystery

Is what Rudi's camera takes in the city

and

Some place any one is someone anyday,

Which Rudi proves here clearly out of Euclid

The album is both playful and serious, ambitious and light-hearted. Clearly intended for the private amusement of a small coterie of friends and fellow artists, 'New York, N. Why?' explores some of the key issues associated with photopoetic texts; these concerns are played out in later examples of the genre but are arguably never quite resolved.

|

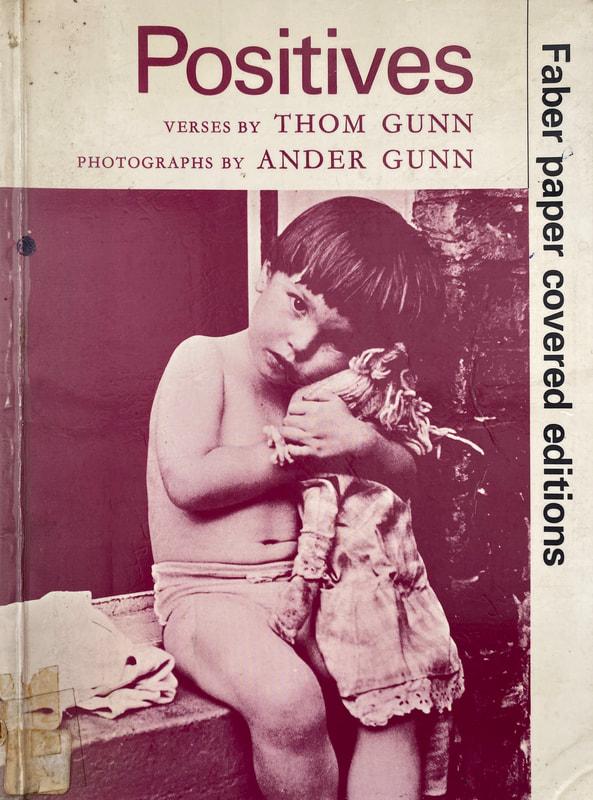

Photopoetry texts often involve collaborations between poets and photographers. Another example of this can be seen in Positives (1966), a collaboration by brothers poet, Thom and photographer, Ander Gunn. The publisher's introduction reads:

In Positives they have joined forces to produce a book in which poetry and visual imagery are used to counterpoint and reinforce each other; and to produce between them an effect more powerful and moving than either would on its own [...] the whole organic series of poems and pictures is a bold, exciting and successful creative experiment. Gunn later wrote that he was "never very sure whether what I was writing opposite the photographs were poems or captions." Each poem is untitled and is placed opposite a photograph. Both poems and photographs chart an un-named, archetypal, working class woman's life from birth to old age. The whole series can be viewed here. Number 8 in the sequence features a tightly framed photograph of a young woman, laughing and smoking in what looks like a social situation. She looks up and away from the camera, caught off-guard.

|

|

She rests on and in

the laugh with her whole body, like an expert swimmer who lies back in the water playing relaxed with her full uncrippled strength in a sort of hearty surprise or the laugh is like a prelude: the ripples go outward over cool water, losing force, but continue to be born at the centre, wrinkling the water around it |

Interest in the Japanese Haiku grew rapidly in the West throughout the 1970s. Ann Atwood's photopoetry books, often designed for a younger audience, explore the similarities in approach of the writer of haiku and the photographer of natural forms. Traditionally, a haiku accompanied by a painting is called a haiga. A photo-haiga is known in Japan as shahai, or 写俳, to differentiate it from traditional haiga.

|

|

Atwood identifies the three elements essential to haiku as time, place and object and compares the poetic processes of close focus and the magnification of a fragment to stand in for the whole as analogous to photography. This is reflected in the design of the book. The words "illustrate the photographs, the three lines being divided in such a way as to unite the two pictures into one haiku."

This book is asking: can art and photography, by applying some of the haiku principles, find an effective way of getting inside nature and seeing it from the heart out? |

|

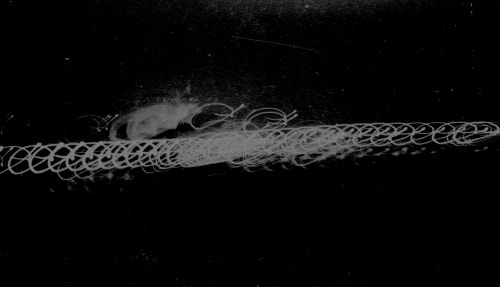

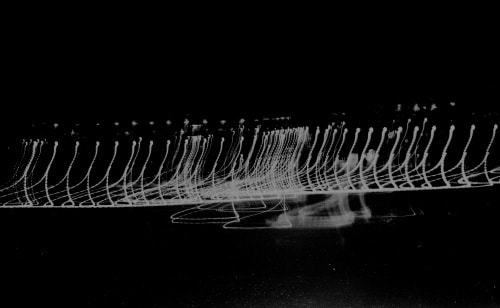

In 1978, the Polytechnic of Central London organised an exhibition entitled Photopoetry. It included works by 50 contributors from 12 countries and was the first exhibition of its kind. This exhibition included works which explored the conceptual relationship between photography and poetry (i.e. concrete poetry) where the distinctions between these separate art forms were blurred or complicated. An example is this pair of photographs by Paul and Clive Fencott in which the brothers attempted a form of light writing using long exposures to capture specific letter forms, in this case 'eeeeee' and 'iiiiiiii'. These images were accompanied by an impromptu performance at the exhibition private view.

|

Allen Riddell wrote about the exhibition: "In some cases the poets' use of photography has been a structural one involving such photographic processes as enlargement or reduction, the reversing of black on white to white on black, or the systematic altering of tonal values by taking exposures of successive time-lengths. Photomontage is another area in which poets have been particularly active recently."

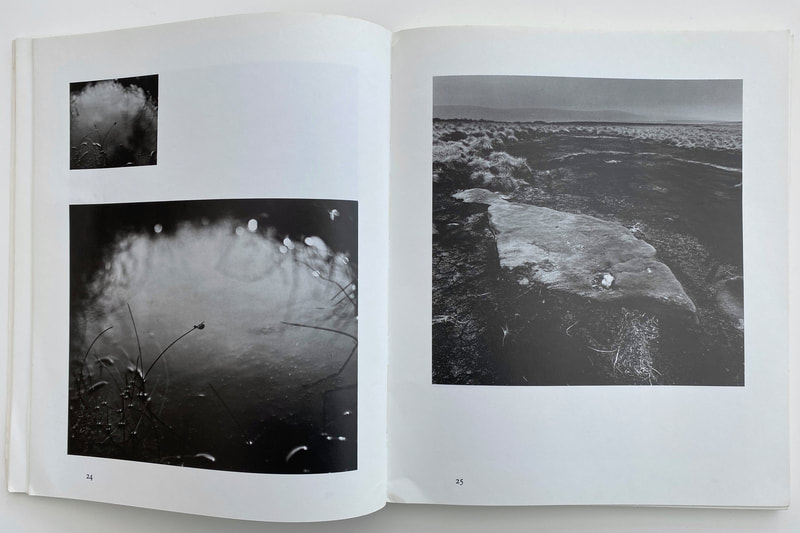

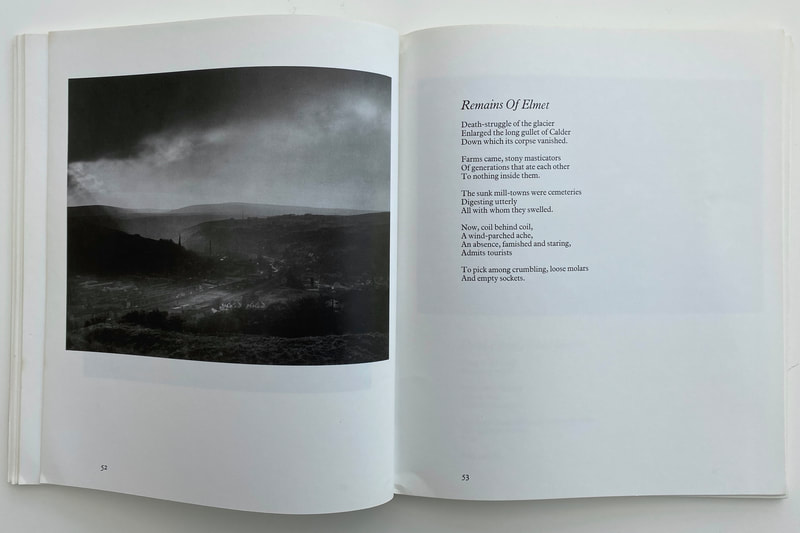

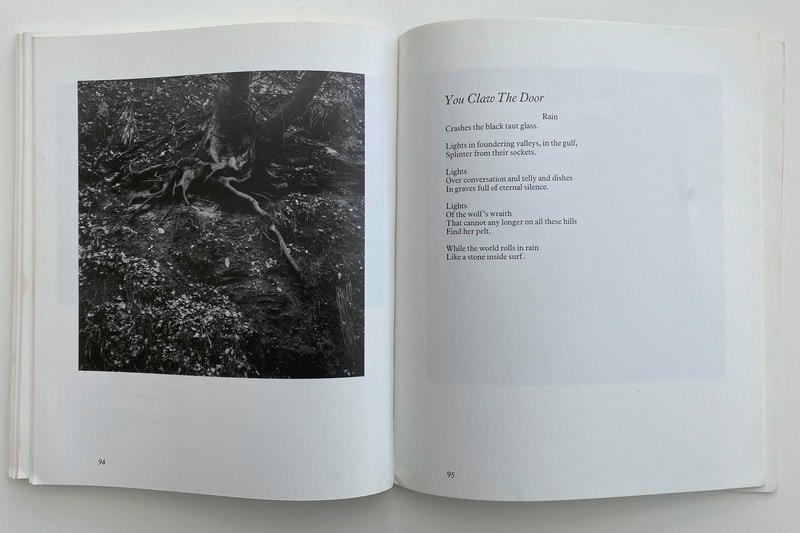

Published in 1979, Remains of Elmet is a poetic and photographic lament for the loss of a way of life in Yorkshire's Calder Valley by Ted Hughes and Fay Godwin. Elmet was the last British Celtic kingdom to fall to the Angles and Hughes reflects on the decline of a once vibrant social and industrial landscape. According to the British Library website, Hughes' "taut verse and Godwin’s evocative photography do not merely describe but also embody the rhythms, sounds and atmosphere of the area."

poetry and photography seem uniquely suited as analogues to each other. Both, independently, deal with the seen and the unseen. The tightness and concision of the lyric poem, for example, reminds the reader of the photographic frame: What is happening just out of shot? One might argue the lyric poem is ‘taken’ in a way similar to the photograph.

-- Michael Nott

Contemporary PhotoPoetry

The following selection of more recent photopoetry publications is intended to provide a variety of examples for study. They are arranged in chronological order and, for the sake of consistency, the name of poet (or translator) is given first, followed by the photographer. We have chosen publications which, hopefully, demonstrate the breadth and variety of photopoetic experiments. The selection is not intended to be exhaustive. We have only referred to publications in our small collection. A video flip through of each book is provided plus a short description of each book and three sample spreads.

In the introduction to Plan B, a collaboration with photographer Norman McBeath, poet Paul Muldoon remembers being "very conscious of the difficulties of poems and photographs responding to each other in kind, of one given 'in return' for the other." The risk is that either the poetry or the photography suffers by comparison or that both are too closely associated, leaving no room for serendipity or ambiguity. In his introduction to Why I'm Here by Lucy English and Sally Mundy, Tim Liardet asks, "Do the pictures provoke the poems, or vice versa?" He concludes that this doesn't really matter "since the reader is encouraged to experience the two together as one form [...] in the business of mutual illumination." In Chinese Makars, Robert Crawford and Norman McBeath's publish a 'Photopoetry Manifesto' which identifies aspects of their shared practice but also offers advice for other photopoetry collaborators:

In the introduction to Plan B, a collaboration with photographer Norman McBeath, poet Paul Muldoon remembers being "very conscious of the difficulties of poems and photographs responding to each other in kind, of one given 'in return' for the other." The risk is that either the poetry or the photography suffers by comparison or that both are too closely associated, leaving no room for serendipity or ambiguity. In his introduction to Why I'm Here by Lucy English and Sally Mundy, Tim Liardet asks, "Do the pictures provoke the poems, or vice versa?" He concludes that this doesn't really matter "since the reader is encouraged to experience the two together as one form [...] in the business of mutual illumination." In Chinese Makars, Robert Crawford and Norman McBeath's publish a 'Photopoetry Manifesto' which identifies aspects of their shared practice but also offers advice for other photopoetry collaborators:

- Poems and photographs encourage each other’s obliquity.

- Photopoetry is more interesting and engaging when the photograph is not a literal illustration of the poem; likewise, if the poem is not a literal description of the photograph.

- Both poem and photograph should be able to stand alone in their own right.

- The pairing of poem and photograph should bring more depth, so each gains something from the collocation.

- Unless the poet has taken the photographs or the photographer has written the poem, the pairing of photograph and poem will involve a collaboration. Collaborations which work are like close human relationships: in a successful pairing of poem and photograph each will be independent yet interdependent.

- The pairing should be about revealing rather than explaining. This is the key to engaging the reader’s imagination.

- The pairing should allow for serendipity. This is partly to do with the process of choosing which pairings to make, and partly due to the power of the pairing to excite.

- Within a set of pairings there should be a range of connective strands: again like a relationship, where there are lots of different facets of attraction and at the same time a deep consistency.

- Photographs should stand free from any title other than the language of the poem.

- The dynamic between a long poem and a photograph is very different from that between a short poem and a photograph; the latter pairing works best in exhibitions.

- People always want to know where a photograph was taken, but in photo-poetry a level of imaginative engagement is lost as soon as they find out.

- A haiku comes closest to the shutter’s click.

|

|

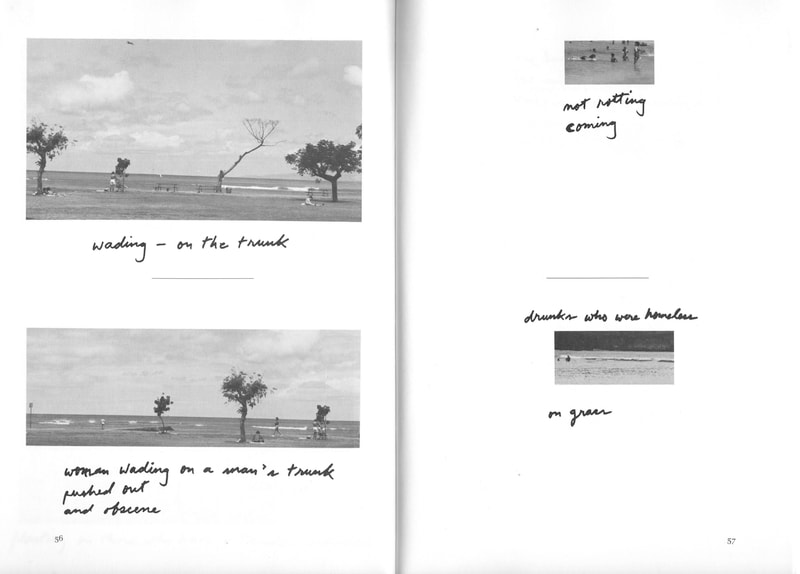

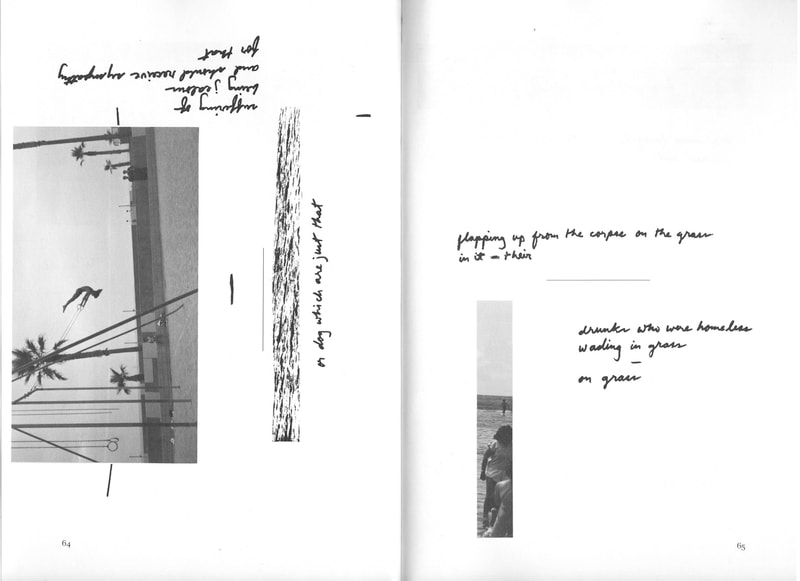

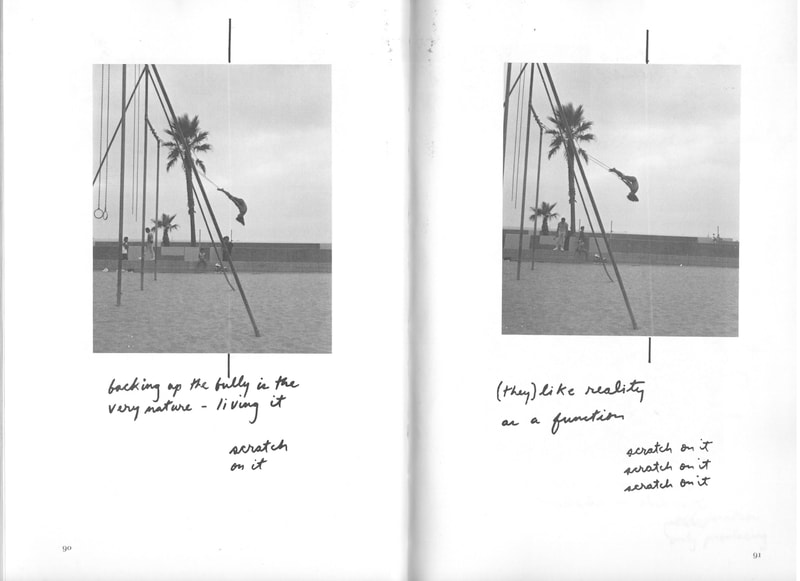

Leslie Scalapino: Crowd and not evening or light (1992)The titular poem has the feel of a handmade photo album. The photographs are placed irregularly on the page, sometimes rotated and dramatically cropped, with hand written captions which promise a relationship between word and image but which subvert this expectation. Eileen Myles considered Crowd and not evening or light to be “panoramic. The constant shuttling from context to context, her refusal to build tension beyond a certain point. Instead, the weave of her writing keeps flattening out and zipping along, always getting wider and wider.” Scalapino herself commented, “I simply put into writing whatever I was thinking as well as seeing—sometimes responding to events at home and issues of writing.”

|

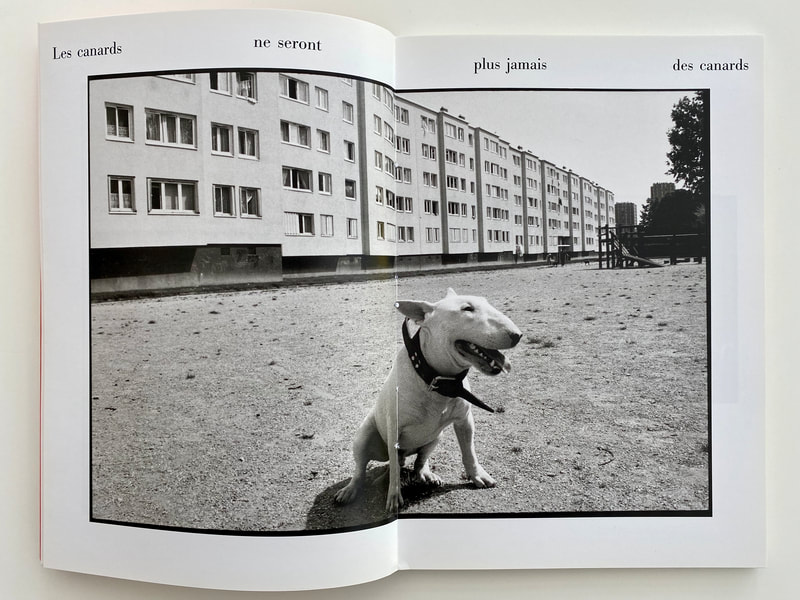

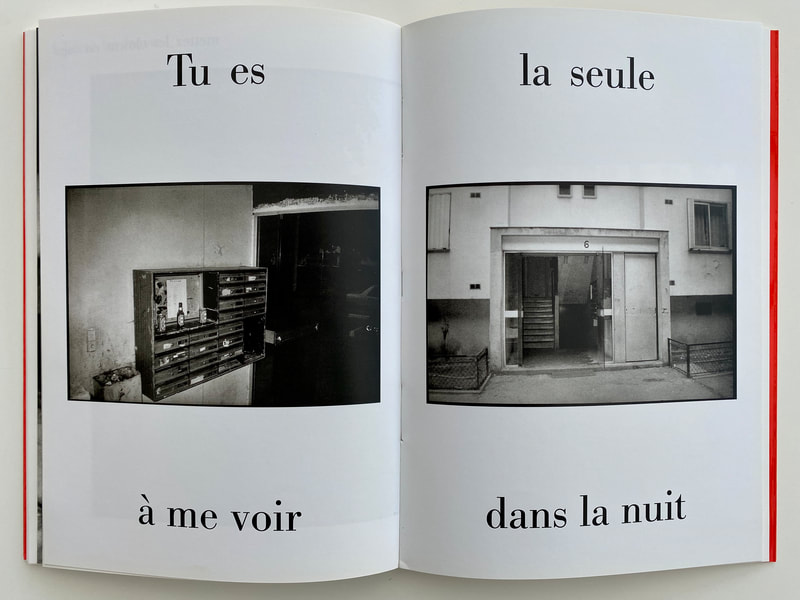

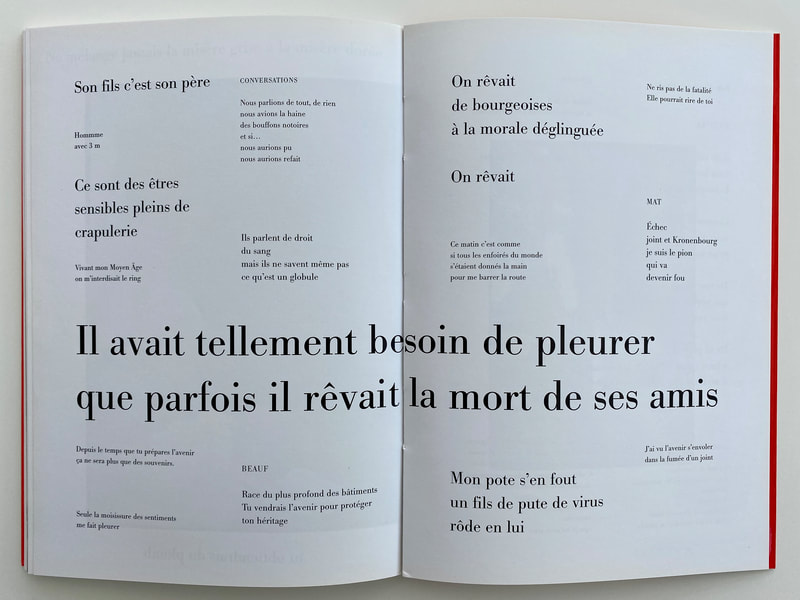

Philippe Tagli: Paradis Sans Espoir (1998)"Paradis sans espoir is a set of poems accompanying photographs of the Parisian banlieue [...] (it) displays a highly original agit-prop account of life in the dreary suburbs around Paris, using personal photographs and corrosive poetic musings that dart and duck the subject matter of the photographic images [...] The vast majority of Paradis sans espoir combines image and text in a tight and tense operation, only allowing the odd page for photograph alone, or for large-print text on its own [...] Tagli would seem to be rejoining the spirit of Constructivist and Bauhaus ‘photomontage’ practice, in which the adding to images of succinct and defiantly contrapuntal language acts so as to make barbed socio-political comments."

-- Andy Stafford |

|

|

|

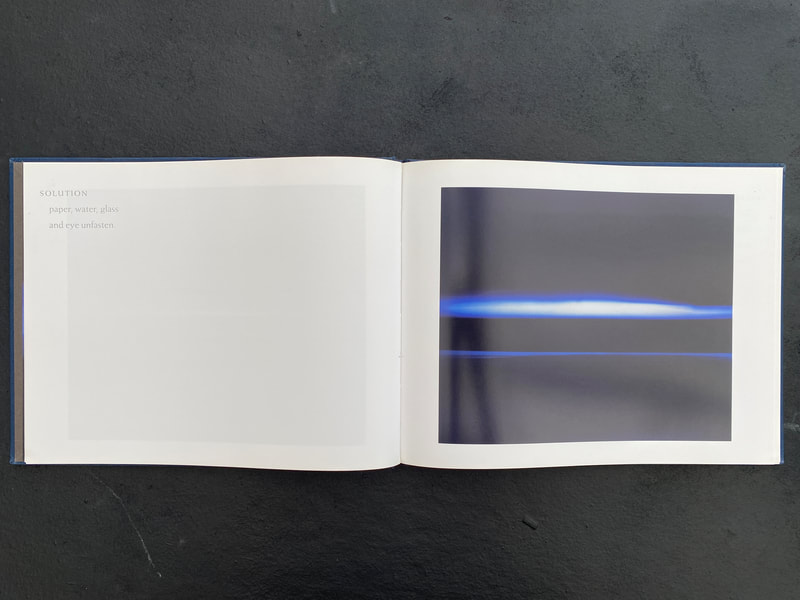

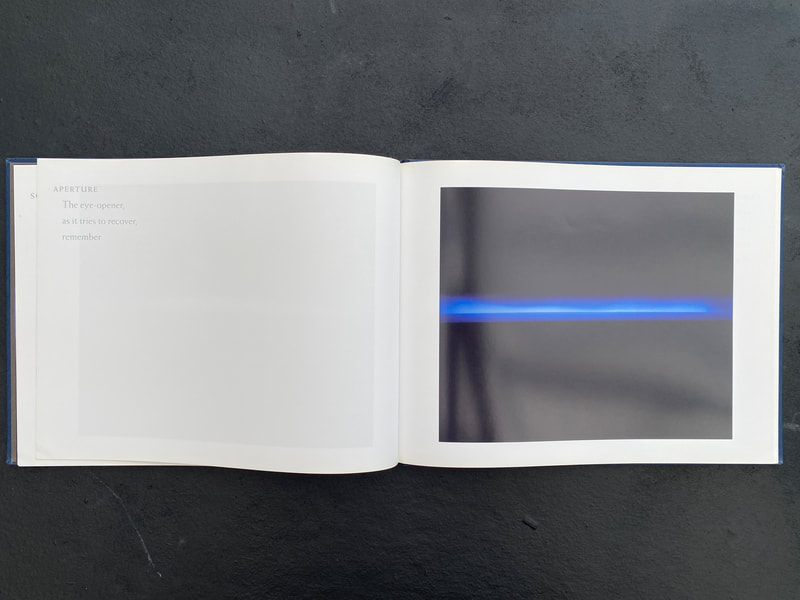

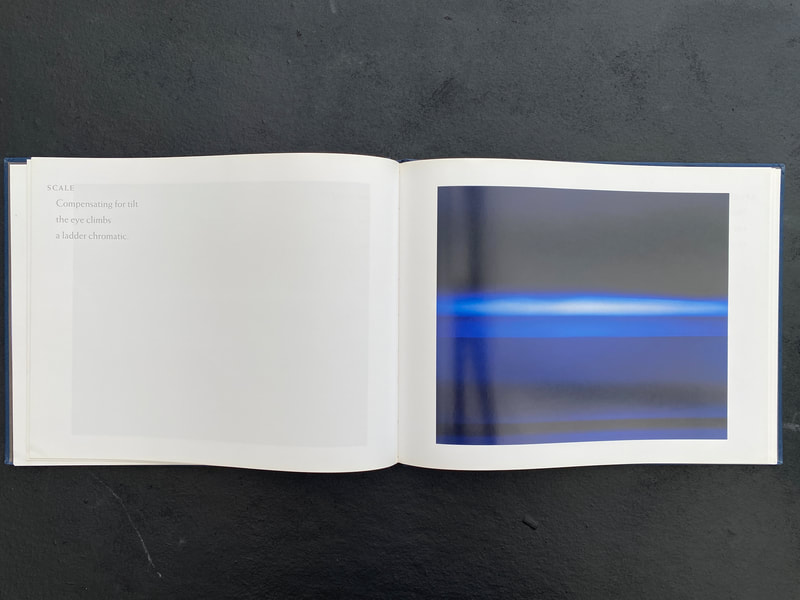

Lavinia Greenlaw & Garry Fabian Miller: Thoughts of a Night Sea (2002)Miller's highly formal, abstract, cameraless photographs are accompanied by a sequence of Greenlaw's meditative poems, reflecting on the images.

"Deeply formal, yet profoundly spiritual, Fabian Miller’s imagery straddles the Modernism of international figures such as Donald Judd, Elsworth Kelly and James Turrell with a sense of essential Englishness, and an appreciation of the sublime." -- History of our World blog |

Paul Muldoon & Norman McBeath: Plan B (2009)Poems and photographs are paired and respond to each other, though one is neither descriptive of nor illustrative of the other. This collaboration reveals the shared perception of poets and photographs, what both set out to 'see' and how their vision is achieved. Poems and photographs seem to converse with one another. Without seeming to strive to do so, this book tests the boundaries between both disciplines and achieves what most photopoetry books aspire to: a symbiosis, a whole which is greater than the sum of its parts. As Muldoon notes, "It would not be too much of a stretch, then, to say that this combination of poems and photographs was curated neither by Norman McBeath nor me but by the poems and photographs themselves."

|

|

|

|

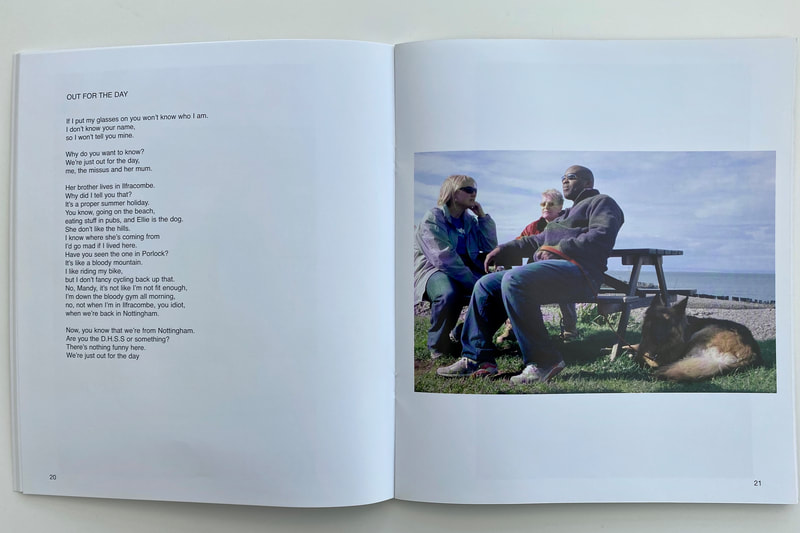

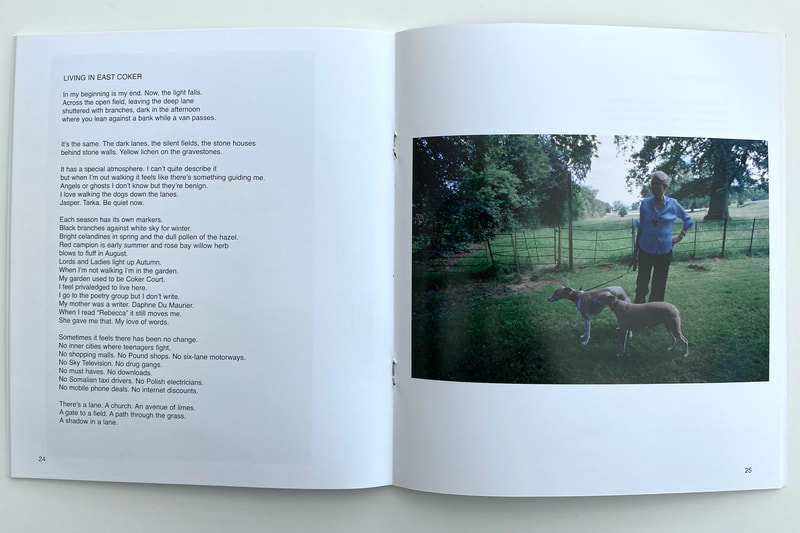

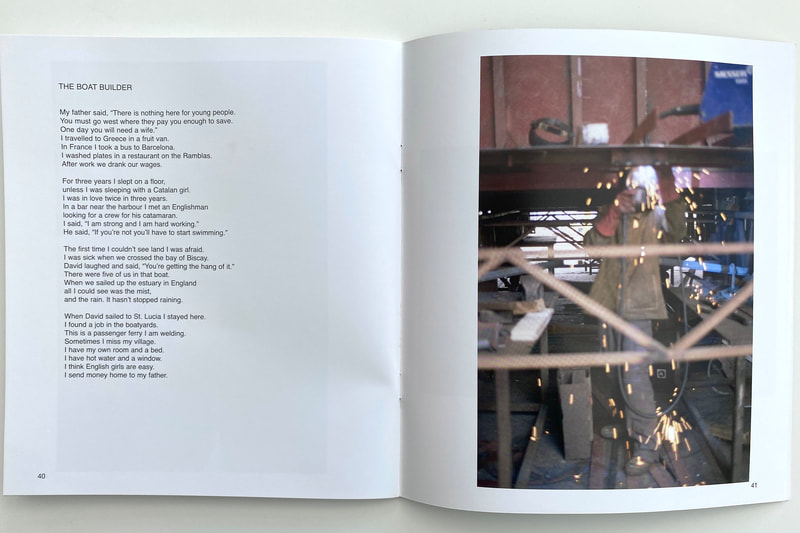

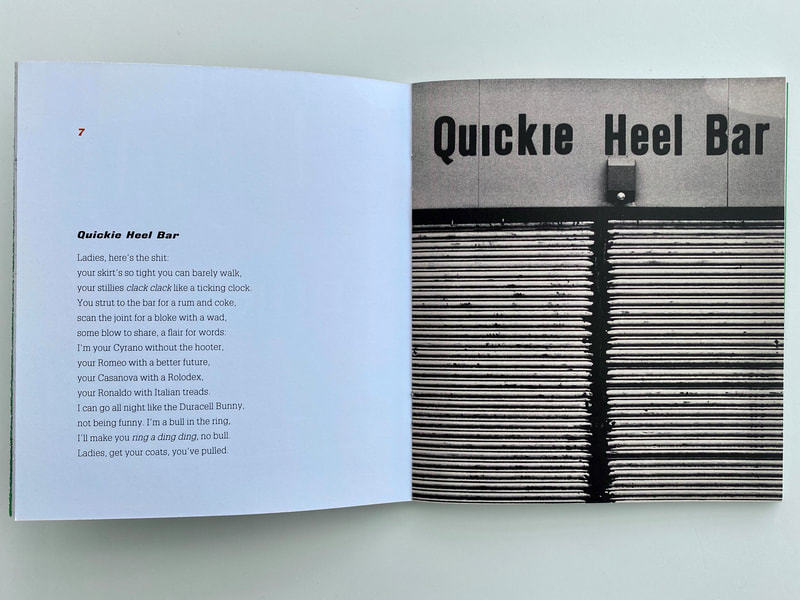

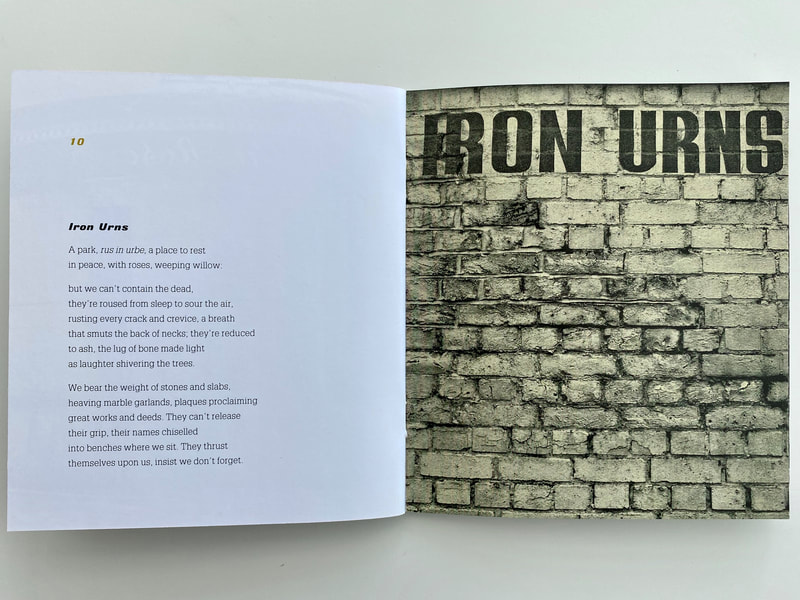

Lucy English & Sally Mundy: Why I'm Here (2009)English and Mundy made a 3 day visit to locations in Somerset during the summer of 2007, recording conversations with people they met in response to the question “Why are you here?” Poems and photographs are paired, the poems in the voices of the subjects of the photographs. Both poems and photographs are the result of conversations with members of the public. Their answers to the question posed by poet and photographer reveal a quiet resilience that feed into the languages used by both artists. Builders, new parents, newspaper sellers, a man in a suit all receive equal attention, clarity and respect.

|

Tamar Yoseloff & Vici MacDonald: Formerly (2012)Yoseloff and MacDonald share an interest in “forgotten corners of a London now fast disappearing”. The poems respond to the photographs of London locations in irregular sonnet form. The poems and corresponding photographs are paired. A pull-out map identifies each location and the poet and the photographer comment on the background to or the context of each of their works.

|

|

|

|

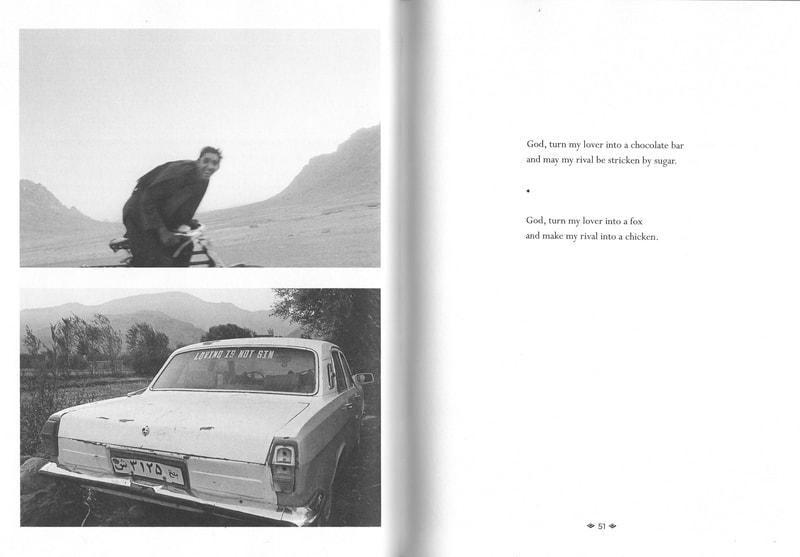

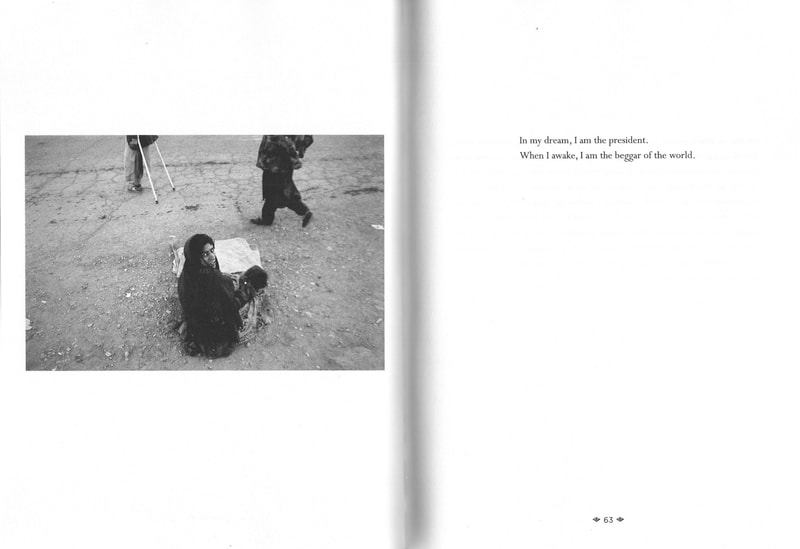

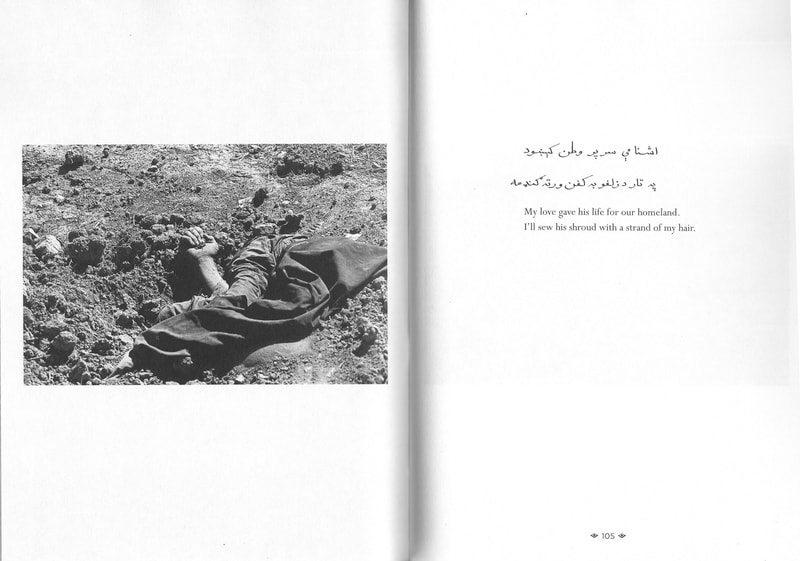

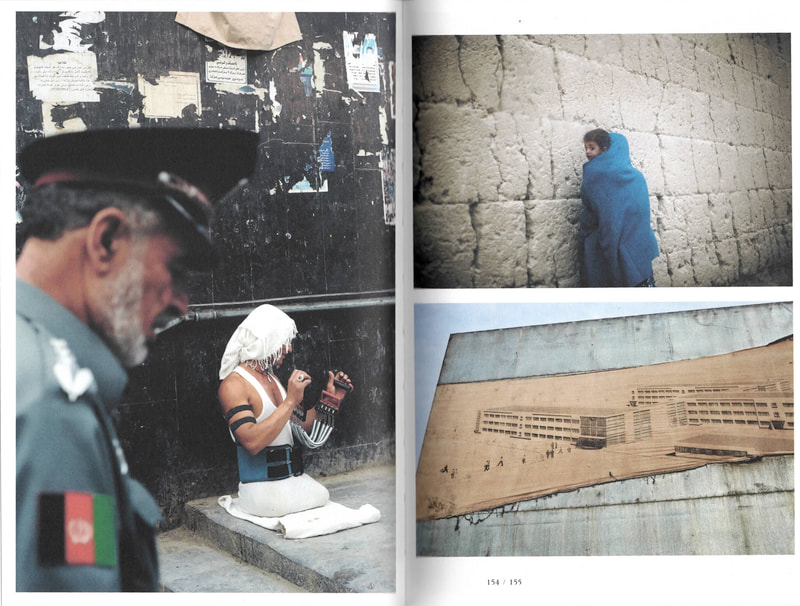

Eliza Griswold & Seamus Murphy: I am the beggar of the world (2014)Poet and journalist Eliza Griswold and photographer Seamus Murphy travelled to Afghanistan is response to a story they heard about a teenage girl who was prevented from writing poetry and burned herself in protest. They returned with a collection of images and examples of landays, an ancient, oral and anonymous from created by and for mostly illiterate Pashtun women. The collection organises the landays into themes of war, grief, separation, homeland and love. The poems and images share some similarities - direct, honest, raw, graphic and poignant.

|

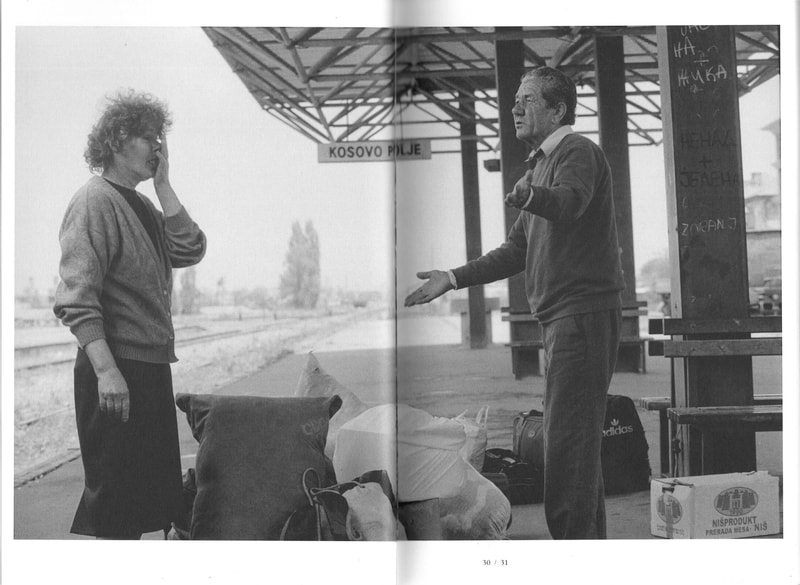

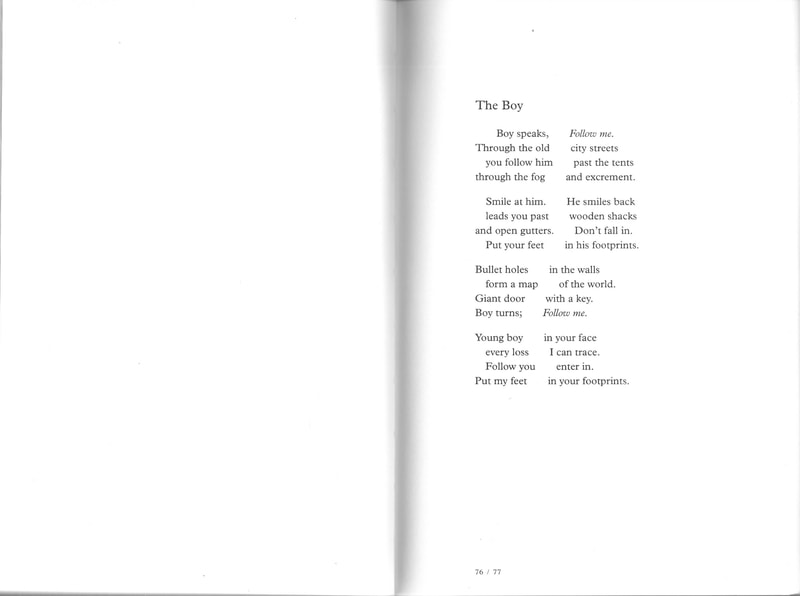

PJ Harvey & Seamus Murphy: The Hollow of the Hand (2015)Harvey and Murphy made journeys to Kosovo, Afghanistan and Washington DC between 2011 and 2014. This book brings together work created on these journeys as well as Murphy’s photographs from the previous two decades. Three sections present work from each of the three locations. In each section a block of poems is followed by a block of documentary photographs. Harvey comments, "I wanted to smell the air, feel the soil and meet the people of the countries I was fascinated with". Murphy adds: "Polly is a writer who loves images and I am a photographer who loves words."

|

|

|

|

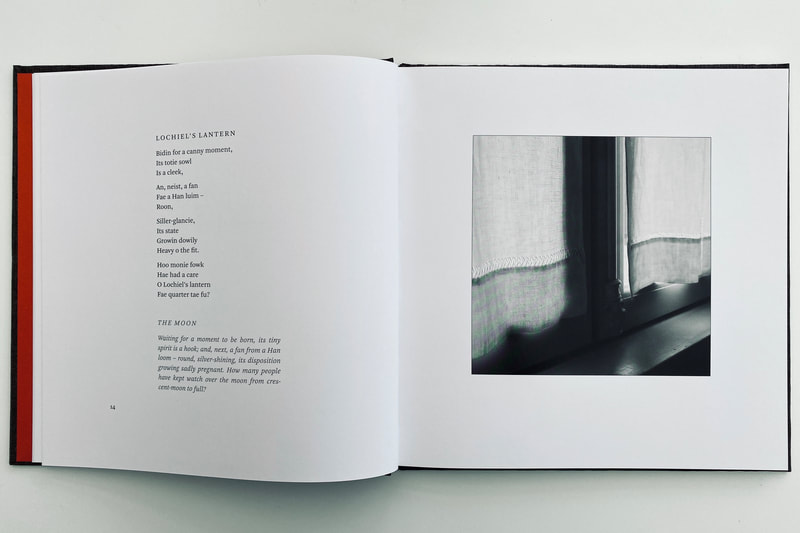

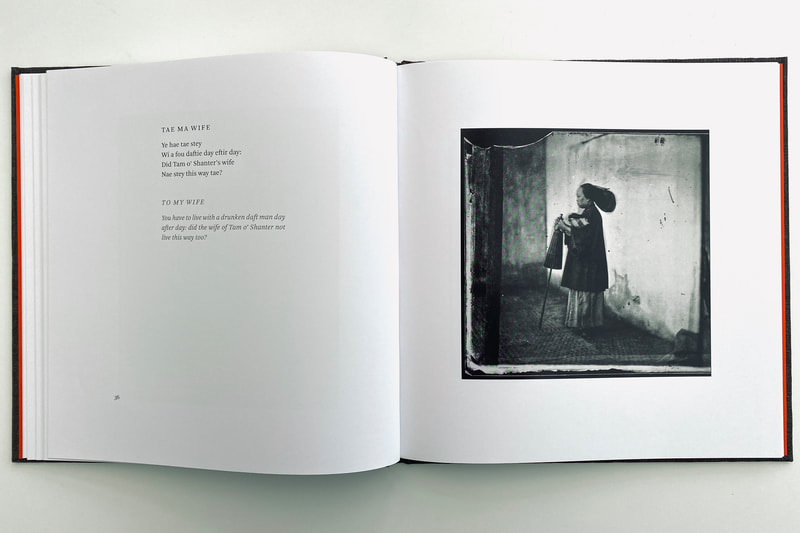

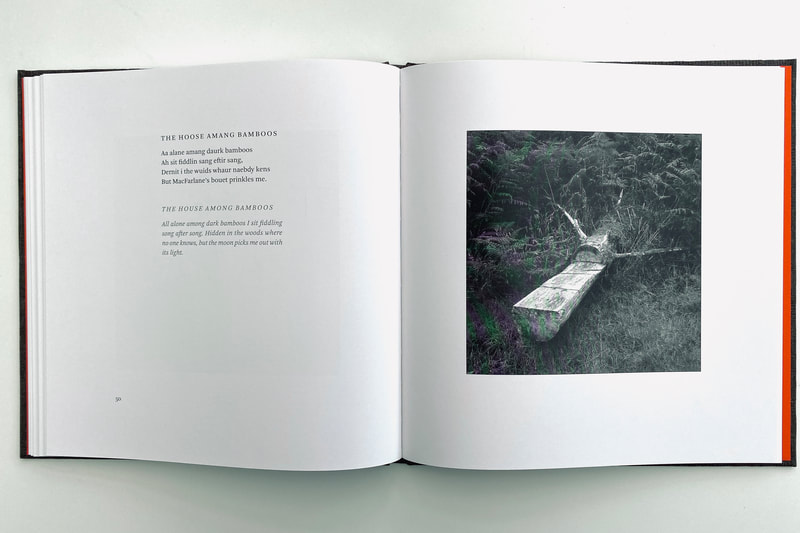

Robert Crawford & Norman McBeath: Chinese Makars (2016)This is a multi-faceted collaboration between poets and photographers from the present and the past. Crawford's translations of work from four Tang Dynasty poets into Scots dialect and then into English prose are placed alongside photographs by the pioneering 19th century photographer John Thomas and the contemporary photographer Norman McBeath. The book is divided into four sections, one for each of the four Chinese poets and, within each section, poems and photographs are interleaved.

|

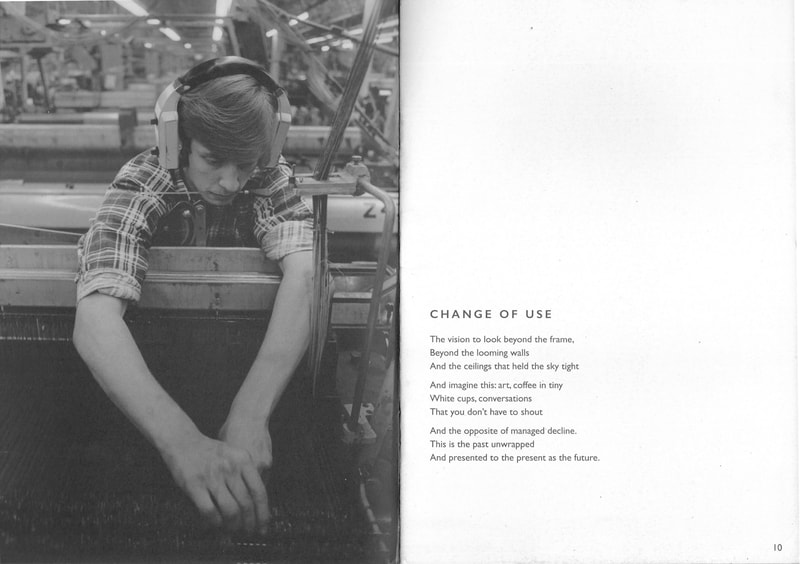

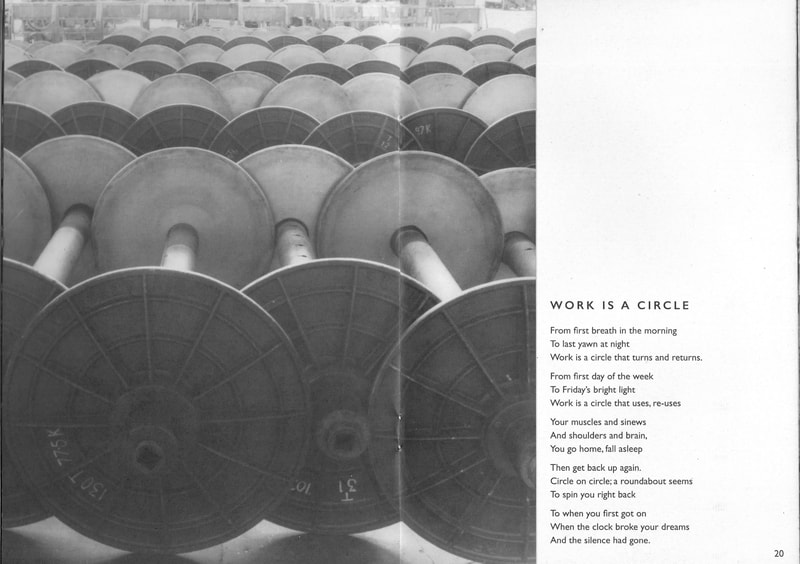

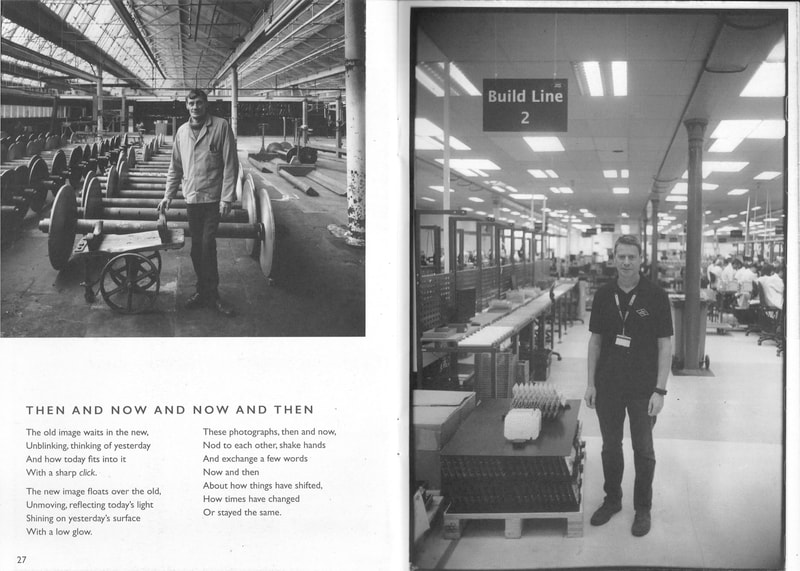

Ian McMillan & Ian Beesley: From Salt to Silver (2017)McMillan writes short poems in response to the archive of photographs by Ian Beesley which document the life of Salts Mills in the 1980s. Photographs are interspersed with poems. The poems appear to describe aspects of the photographs, sometimes commenting directly on them, sometimes writing admiringly about the qualities of photography and sometimes comparing the similarities and differences between the art forms.

|

|

|

|

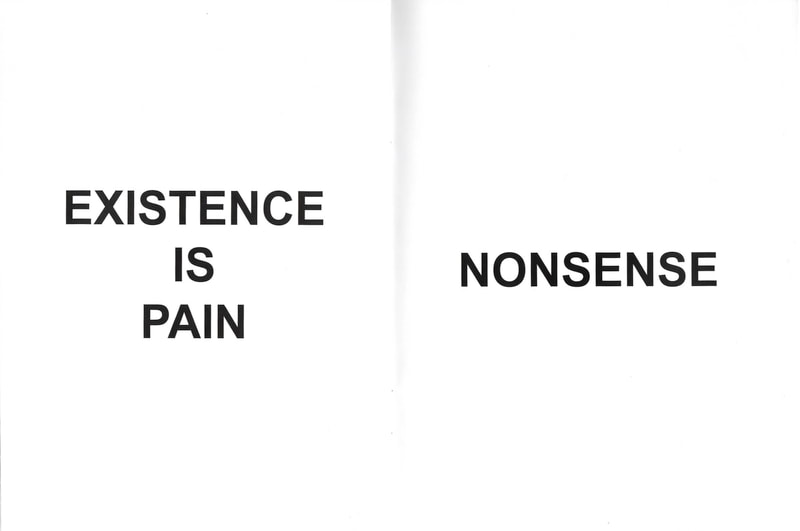

Hans Eijkelboom: New City Poetry (2018)This photopoetry zine presents photographs of people in urban spaces wearing T-shirts with slogans. The slogans are printed separately as if they were pithy, poetic phrases, and these are then followed by sequences of street photographs showing the slogans in the context of fashion decisions. The aphorisms state 'truths', offer advice or make social commentary. When seen photographed on the T-shirt of the wearer, the slogans reveal something of the identity of the wearer, often with elements of disjunction, paradox or irony. For example, a girl appears to snarl whilst wearing the slogan:

GIRLS BITE BACK |

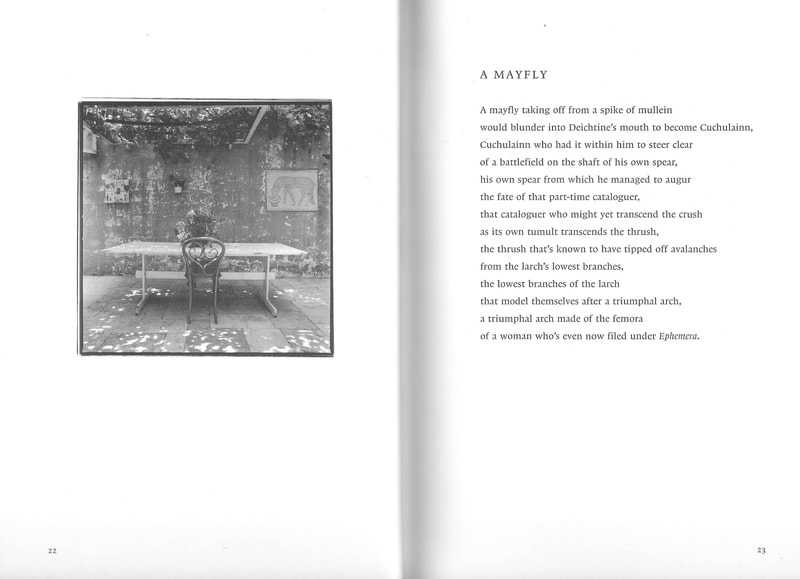

Brendan Cleary & Eadweard Muybridge: Do Horses Fly? (2019)Cleary writes a sequence of poems in response to an archive of pioneering early photographs by Eadweard Muybridge. Poets and photographs are interleaved. At the back there is a detailed section of notes to the poems and to the photographs. Cleary imagines the world of the photographs, projects himself back to the days when Muybridge's inventions began to change the way we see the world. The photographs are provocations for imaginative enquiry and they are reproduced as parallel visual statements rather than illustrations.

|

|

|

|

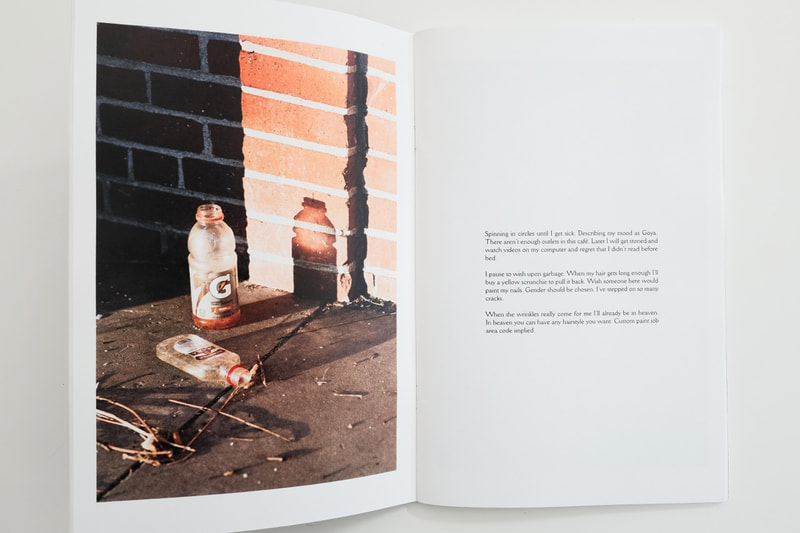

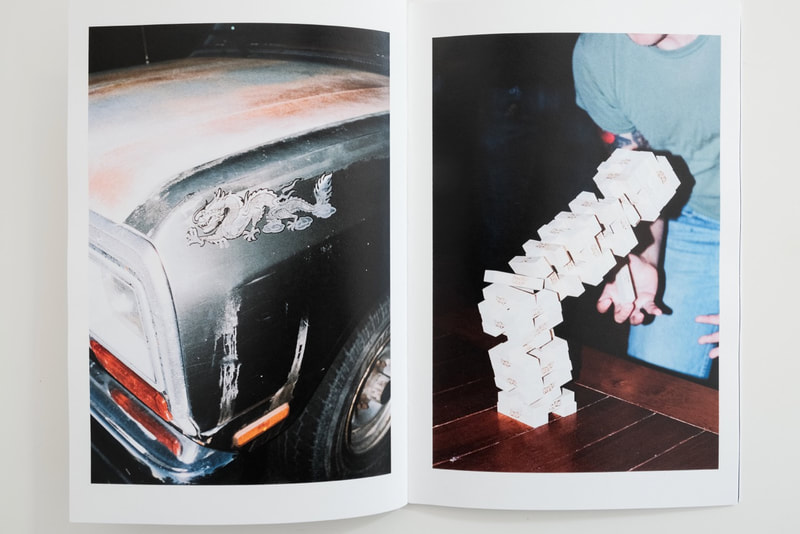

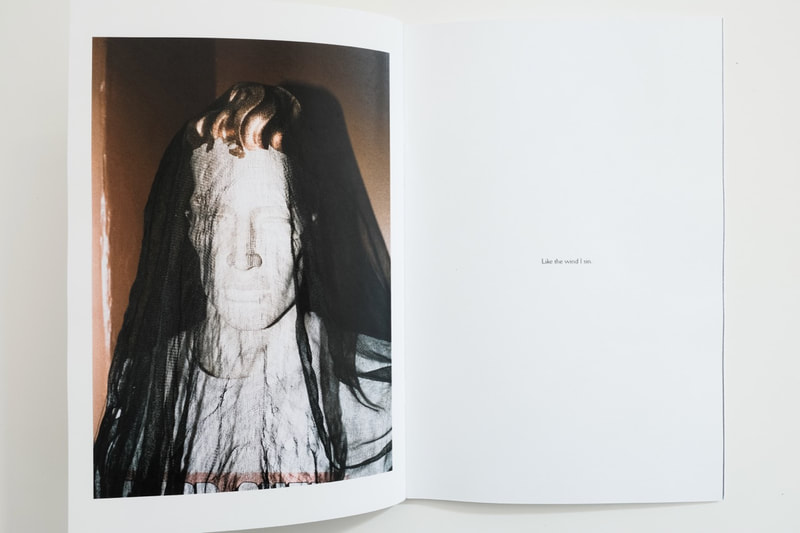

Christian Michael Filardo: Gerontion (2019)"What struck me first about the photographs was the banality of the subject matter, and I approached the texts narratively, as if they could somehow “decode” the images. But soon one realises the texts reinforce the ephemerality and evanescence of the images. References to dreams and death, shifts in appearance and gender abound. Instead of placing the reader/viewer, the texts dislocate and destabilise. They are truly “dreamlike” in that each is a small, internally contained narrative, the significance of which remains ambiguous."

-- PhotoBook Journal blog |

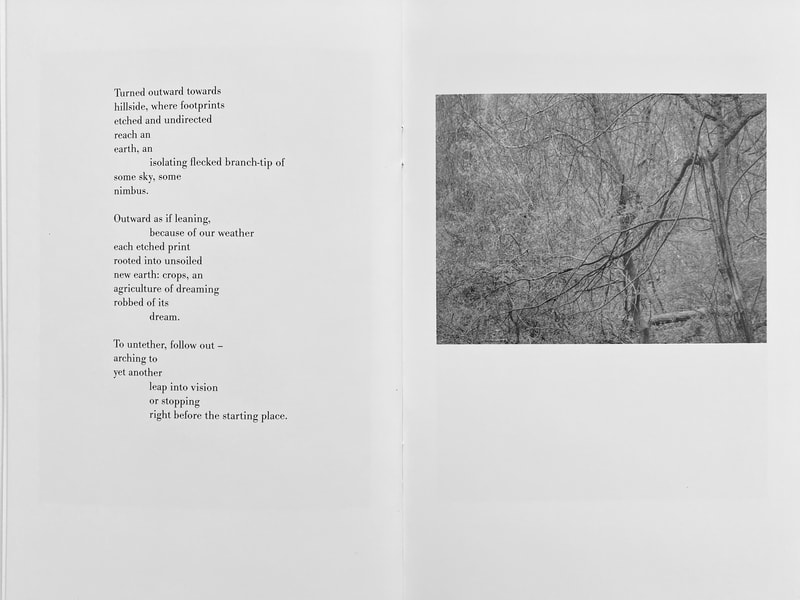

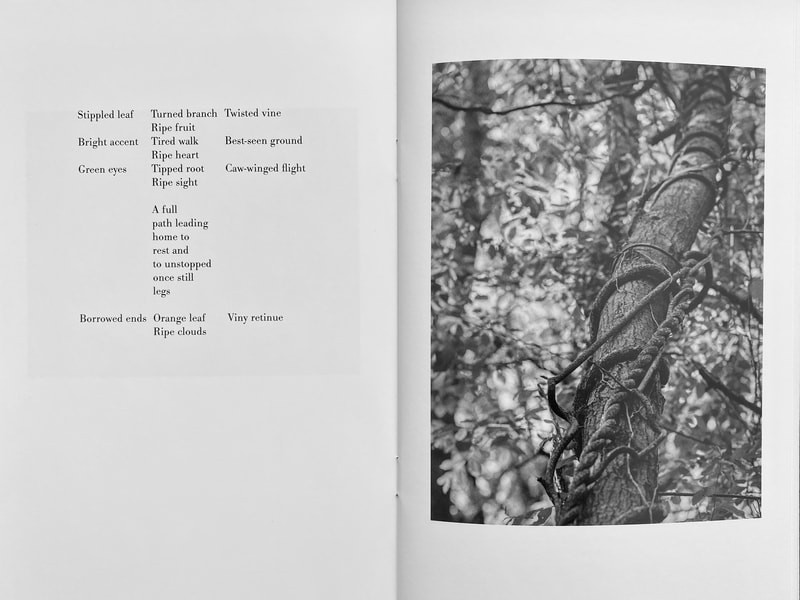

Peter Ward (Ed.): Hillside: Further Selections from The Archive of Bernard Taylor (2020)"Bernard Taylor lived near the elementary school, his front door facing one of the entrances to Hillside Woods. Further information about other former residents of this area is found in my larger survey of Taylor's work, The Archive of Bernard Taylor [...] These photographs and poems were not included in that far more expansive selection of Bernard Taylor's archive [...] Though a modest volume, it is not an afterthought [...] I am grateful to Tom Lecky of Understory Books for his encouragement." -- Peter Ward, Autumn 2020.

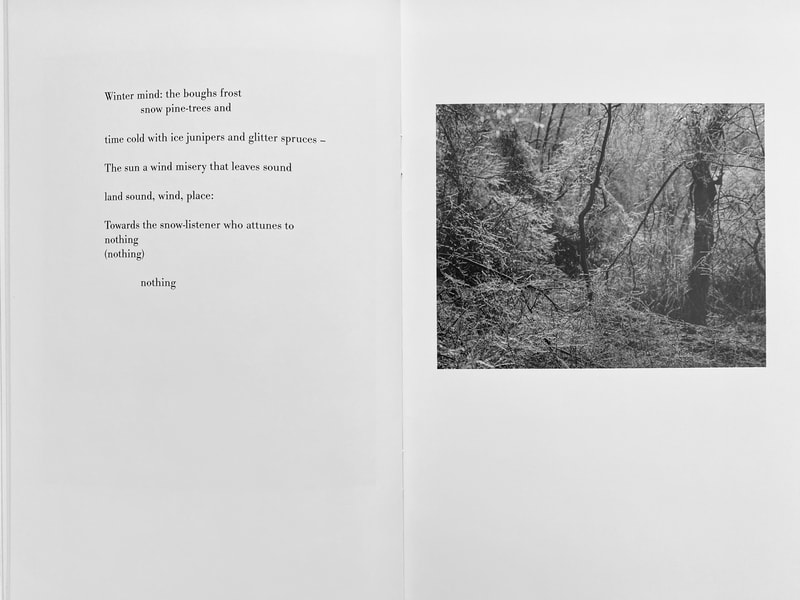

The mysterious collaboration between Taylor, Ward and Lecky is further developed in this chapbook which contains landscape photographs and poems which seem strangely familiar. |

|

Compare, for example, the poem that appears towards the end of the book beginning "Winter mind" with Wallace Stevens' 'The Snow Man':

|

Winter mind: the boughs frost

snow pine-trees and time cold with ice junipers and glitter spruces - The sun a wind misery that leaves sound land sound, wind, place: Towards the snow-listener who attunes to nothing (nothing) nothing |

The Snow Man

One must have a mind of winter To regard the frost and the boughs Of the pine-trees crusted with snow; And have been cold a long time To behold the junipers shagged with ice, The spruces rough in the distant glitter Of the January sun; and not to think Of any misery in the sound of the wind, In the sound of a few leaves, Which is the sound of the land Full of the same wind That is blowing in the same bare place For the listener, who listens in the snow, And, nothing himself, beholds Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is. |

Some suggested activities:

- Create a series of photographs in response to an existing collection of poems. For example, you could attempt to re-present older, well-known poems, imagining you have commissioned to create new images to accompany a publication aimed at a younger audience. Alternatively, you could select more contemporary poems (either by the same author or by a range of poets but on a similar theme) and attempt to provide a parallel photographic expression of the main ideas, moods, characters and situations etc.

- Write a collection of poems in response to existing photographs. Will you choose a particular poetic form - haiku, sonnet, villanelle, sestina etc. - or will you wrote in free verse? Will you choose famous, historic photographs or more contemporary examples? Will your poems be about the photographs (an attempt to describe aspects of the images) or be separate, parallel works of art? Will you experiment with innovative typographic design (perhaps inspired by some of the Surrealist photopoetry examples above) or do you prefer more conventional approach to the presentation of your poems i.e. poem and photograph on facing pages?

- Collaborate on the creation of a new, original photopoetry publication with a writer/photographer. Will you both contribute poems/photographs or separate your roles? Is there someone you know who is studying or interested in photography and/or creative writing with whom you could collaborate? Are you able to use social media to connect virtually (and safely) with a collaborator? Could a teacher help facilitate a collaboration with another student/class in school? Will you choose to publish your work as a book, zine or pamphlet or could the collaboration be shared on the Internet in some form - a blog, a website, a video etc?

- Create a series of photographs based on 'found' poems. Found poetry (like the slogans on the shirts photographed by Hand Eijkelboom in New City Poetry) is usually hiding in plain sight. For example, you could 'find' these poems in newspapers, magazines or on the Internet by using Brion Gysin's Cut-Up method). You might make notes of text you 'find' on the street - signs, posters, advertising hoardings etc. - combining them later into poetic shapes.

- Write you own poems and take your own photographs. If you feel confident in both art forms, why not have a go at doing the whole thing yourself? What will come first - the words or the pictures? Perhaps they will evolve in parallel.

Additional Resources:

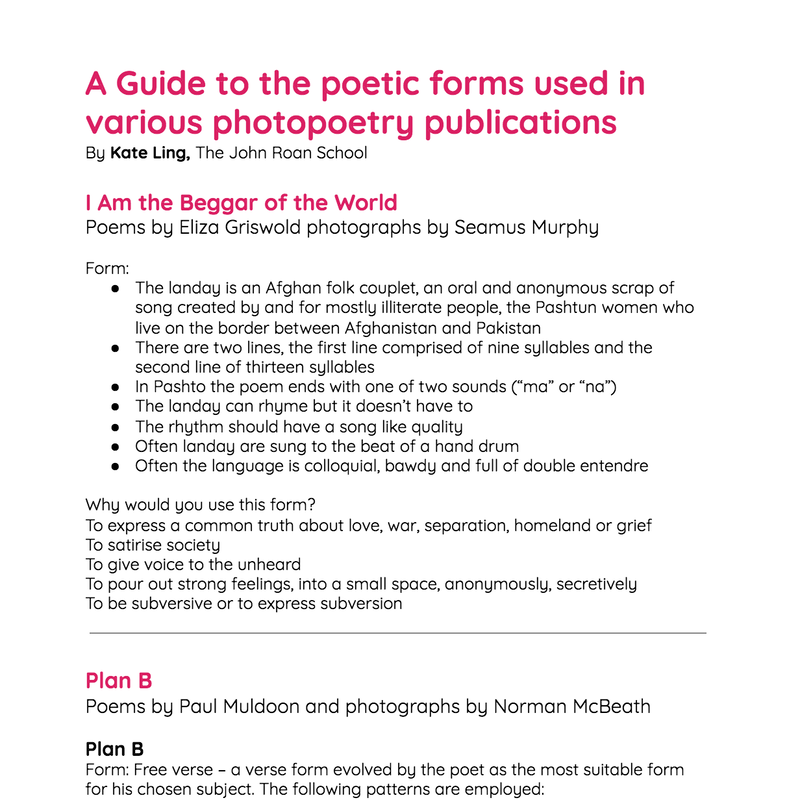

A Guide to the poetic forms used in various photopoetry publicationsPoet and teacher Kate Ling (@katelingpoet) has written this accessible guide to the poetic forms employed in various photopoetry publications. This will be particularly useful to any students attempting to write their own poems but also to the students of photography who may be less confident in evaluating the literary component of photopoetry publications.

|