Prior to working in China, I had completed a MFA specialising in photography and moving image at Massey University, Wellington in 2016. It was during this study that I had participated in a 2-week artist residency in Singapore and, while there, discovered the work of Shanghai photography duo, ‘Birdhead’ in a local art gallery exhibition. Birdhead’s casual attitude and use of traditional Chinese craft techniques seemed refreshing to me. Until this point I had largely been influenced by European innovators such as Juergen Teller, the more subtle Anders Edström, and well-known Japanese photographer, Araki. My MFA research focused on the atmospheric street photography of Japanese Provoke era photographers such as Takuma Nakahira and Daido Moriyama along with younger digital photographers who were producing work in dialogue with emergent internet technologies and aesthetics. So even before I set foot within The Middle Kingdom, my interest in aspects of Asian aesthetics was piqued, and I appreciated the degree of sensitivity towards practices of observation that are perhaps not as developed within Western photography traditions.

I began my first teaching contract in China in 2017 and had built a lifestyle around spending half the year in China teaching and working on personal photography projects, and the other half freelancing as a photographer in Wellington, New Zealand. Prior to my first contract in China I had taught at several NZ based institutions, where I had developed a somewhat free and open student-driven pedagogy, while being nimbly receptive to student need and desire. But my immersion into the Chinese university system was an abrupt culture shock, which offered both personal learnings, and opportunities for innovation within my teaching practice.

At this point I should note that my Chinese language ability was poor (albeit I’m now attending Mandarin night classes in New Zealand), and the English language abilities of individual students was diverse. Additional challenges to teaching in China were around technology and access to research material related to the topics we covered. The students each had a portable computer or tablet and a mobile phone, and local internet access, and most but not all of my teaching rooms had a projector for delivery of teaching materials. I was supported by a translator (human), and while this slowed the flow of dialogue between myself and students, it did enable a workable starting point to explore ideas specific to Western art history and contemporary photography practices, within a Chinese context. I’m grateful for the students' patience as I adapted to the new environment in those early weeks of teaching.

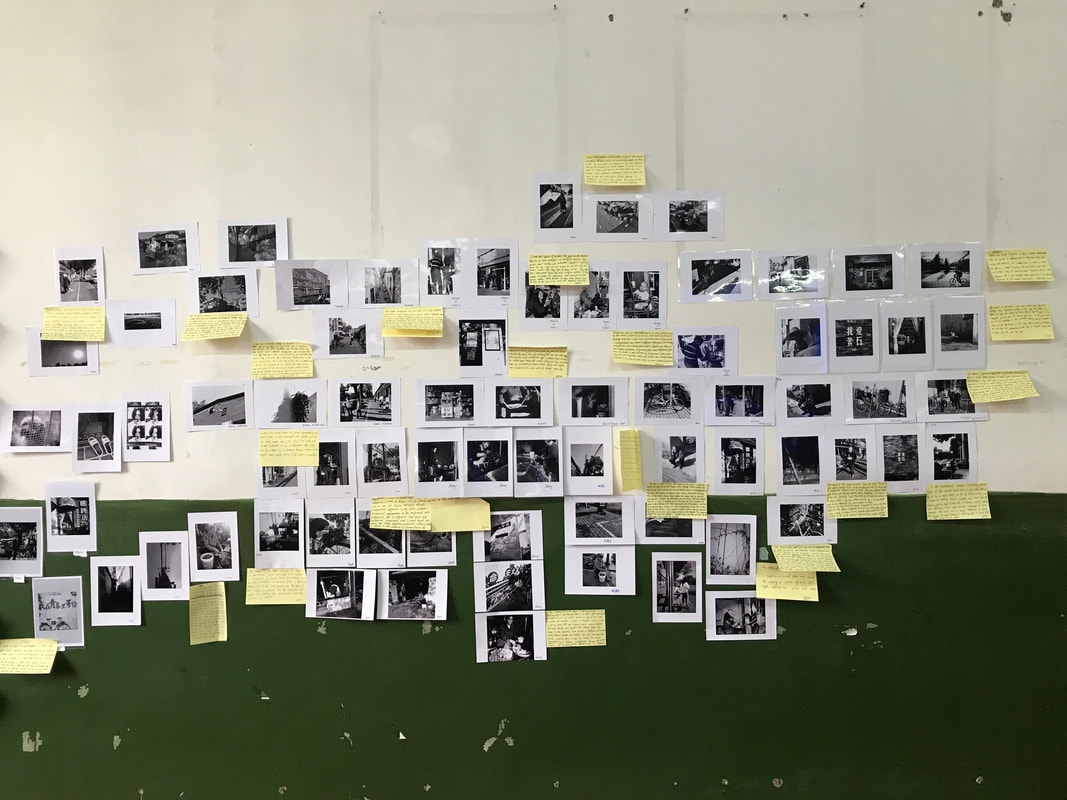

I have made use of a few of the teaching plans found on photopedgaogy.com as shorter warm-up projects before the students embark on their main assignments. A lesson plan I found particularly useful was ‘Wrong’. Based on John Baldessari’s artwork of the same name, the project introduced students to postmodernism in a way that directly activated their willingness to explore unconventional composition in photography and consider by what/whose standards an image is judged. I found this to be an excellent point of departure to explore post-modernism in more depth and allow students to express their own culture and aesthetic sensibility within the post modern paradigm. Using post-it notes was a useful way to engage the students to share their thinking with the group, though as teaching has now shifted to online classes, I have replaced physical post-it notes with Padlet.

By studying the well-crafted and thoroughly researched content found on photopedagogy.com, I have learnt to take an idea found in art history and consider how it could lead to a contemporary photographic response. Ideas found in art history must be useful for the students' studio practice. Otherwise, my experience is that engagement levels are drastically reduced. After quite a bit of experimentation I found that a modular approach to the structure of the course content helped students apply the same pattern to the following modules and therefore focus more on the content. I found this avoided confusion regarding assessment.

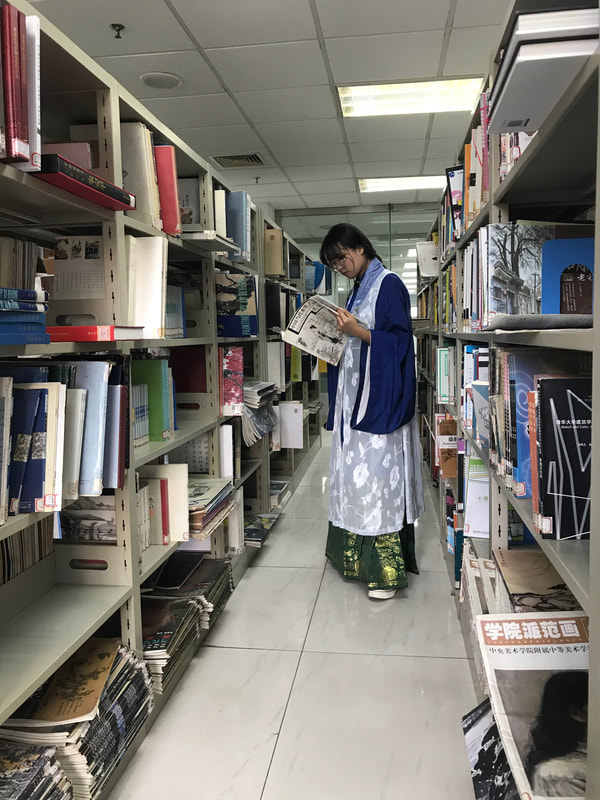

The students produce photography and video work using their smartphones. The convergence of computational photography and internet connectivity is an exciting development for photographers and teachers. I found my students to be ultra-fast adopters. If a particular technology worked and achieved a successful outcome, they were keen to work with it, especially if it saved time! Using the camera as a tool to explore visuality, combined with emergent internet aesthetics, is an exciting opportunity to expand photographic practice. Fragmented information, fake information, instant communication and sharing, etc. has challenged the 'truth claims' of photography. The instability of the image has resulted in a new aesthetic consciousness where the photographic image is no longer “fixed” and authorship is malleable. But these are issues now taken for granted by a younger generation of image makers.

Ultimately I believe photography pedagogy has shifted dramatically by recent technological developments and world events. The mobile phone incorporates the hybridised technologies of camera hardware, software, and internet connectivity. This enables elements of traditional approaches to photography to converge with video, editing, and curating imagery for communication via social media platforms. Almost everyone has access to this technology now, so I believe the new phase of photo-thinking is shifting towards how the device can be used for innovation. Practices making use of machine learning and Internet tools are still being established. I’m now wondering how can this globally fragmented imagery be reconfigured using the accessible technology across time, space, and culture?

I don’t know what the future of professional photography will look like, but I can see the value in students developing a visual literacy that will be of use in a myriad of socio-cultural and commercial contexts. Developing a trans-cultural pedagogy seems to me to be a very relevant pursuit in the 21st century.

In my own country, much has been said about teaching students how to think rather than what to think, but my experience of education across cultures is that even teaching students how to think is fraught. I am continually having my own thought structures and visual perceptions challenged in very healthy ways. I therefore feel the path forward for my personal pedagogy is to explore strategies that encourage students to research relevant ideas found in a trans-cultural art history, which can then be used to support innovative uses of smart phone technologies to visualise their own experience of contemporary life.

www.danielrose.nz / photobasic.co

RSS Feed

RSS Feed