Hi! My name is Tjasa and I am a preschool teacher in Slovenia . I work with three-year-old children, who are very curious about anything new. Our preschool is very open to new ideas, including supporting the creative development of children in all areas. Therefore, with the support of the preschool management, we have decided to include the teaching of photography.

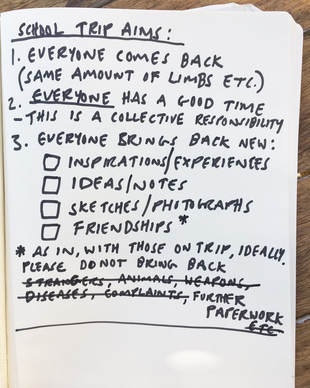

The Slovenian kindergarten curriculum includes several aims which may relate to photography:

- Stimulating curiosity and enjoyment of art;

- Encouraging the experience, expression, and enjoyment of beauty;

- Experiencing and learning about artistic works;

- Nurturing and developing individual creative potential in the phases of experiencing, imagining, expressing, communicating, and asserting oneself in artistic activities.

Despite having a children's camera available, I still prefer to use my personal camera, a Fuji x10. My three-year-olds use it under my supervision. I believe that children can also learn a lot by using semi-professional equipment, while ensuring their safety and using the camera with my support.

The teacher plays an important role in teaching photography to preschool children. As an expert, they must understand the importance of play and exploring the world, so they must use pedagogical methods that are suitable for this age group. In addition, they must encourage children's creativity and imagination to motivate them to create their own photographs and express their ideas and emotions.

The teacher also plays an important role in selecting and evaluating the photographs that children create. They need to choose those that are appropriate for showing to other children and encourage self-criticism so that they can improve and progress in their work. This process should be carried out according to the child's age and individual abilities. The teacher can support children to express their ideas and develop their motor and cognitive skills.

Children who are barely three years old still have small fingers so holding and operating a camera can be a challenge. In addition, children at this age are still in the process of developing their cognitive abilities, which means that their understanding of the world is limited. Here are some ways you can teach a three-year-old the basics of photography:

- Use a simple camera. To teach photography at the age of three, use a simple and safe camera that children can operate themselves. You can also use a smartphone camera.

- Use simple commands to help the child understand what to do. For example, you can say, "Press the button to take a picture" or "Hold the camera with both hands."

- Choose simple objects to photograph. Start with simple objects that the child can photograph. This can include toys or objects found in nature.

- Encourage their creativity. When teaching photography, it is important to encourage the child's creativity and allow them to photograph things that interest them. Let them experiment and explore, as they will experience both the best and worst results.

- Praise the child. Praise the child for every picture they take, as this will make them feel more confident and enthusiastic about photography.

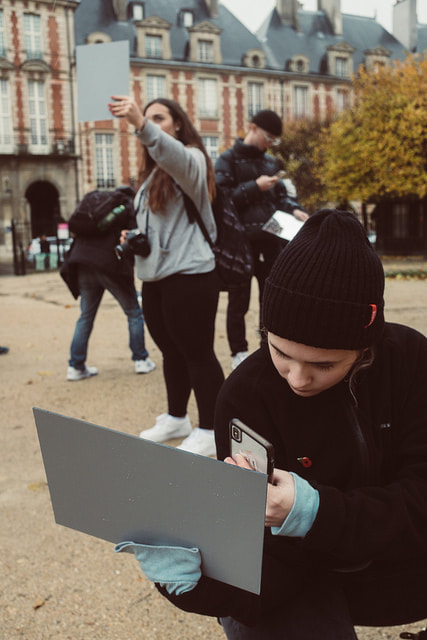

Preschool children are very curious and eager to explore the world around them. Children who take photos will learn to observe the details in their environment, developing their observation and perception skills. Photography can also help develop their motor skills as they learn to hold the camera and press the shutter button correctly. Learning photography can also encourage confidence and independence in children, as they learn new skills and feel proud of their accomplishments. Additionally, photography can help children learn about new technologies and tackle the challenges brought about by the technological world. With help, children can create exhibitions of their photographs. These can be a great opportunity for them to learn about other cultures. This builds confidence and empathy.

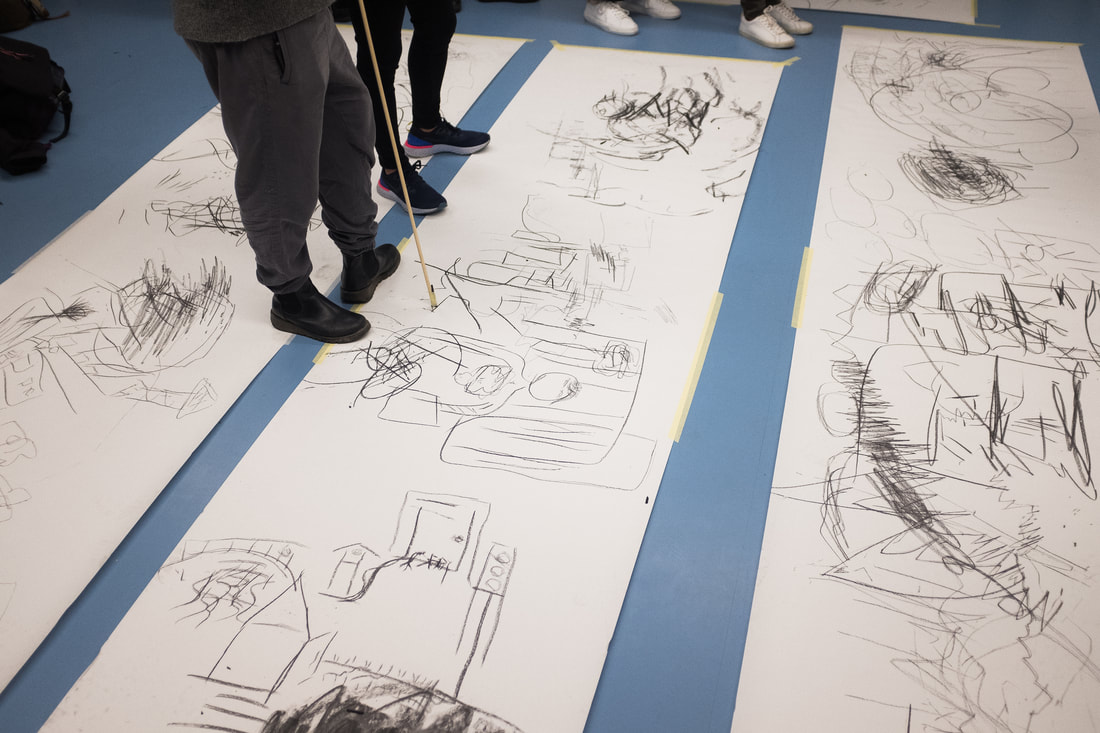

The children were all very different from each other in their understanding, perception, and coordination so I adjusted my approach to each individual. Some quickly grasped the basic instructions and soon started looking for their own shots, taking pictures of their friends playing, their teachers, toys, decorations, and more. Others needed more guidance, more precise instructions, and, above all, a lot of repetition. Some children lost interest in taking pictures after their initial curiosity.

When reviewing the photographs with the children, I was careful to comment on what I saw, saying things like, "Ah, I see you took a picture of a dinosaur." I refrained from evaluating the shots or the photographs themselves. At this age, I think it's most important for the child to fall in love with this kind of activity. The process is currently more important than the final product. However, when they have mastered the basics, I will take a more critical approach to the process of photography - from framing to commenting - and guide them towards self-reflection.

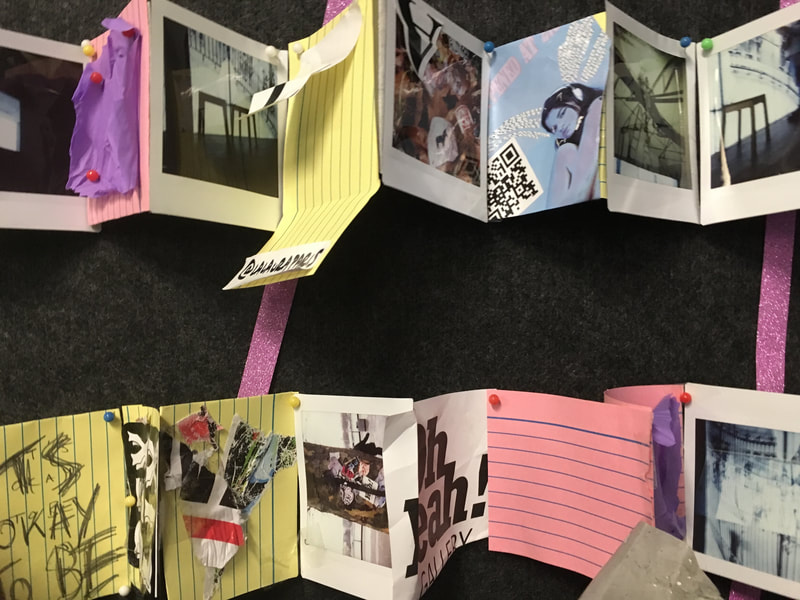

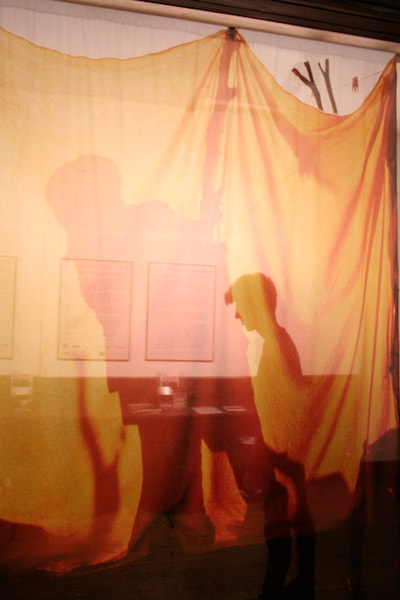

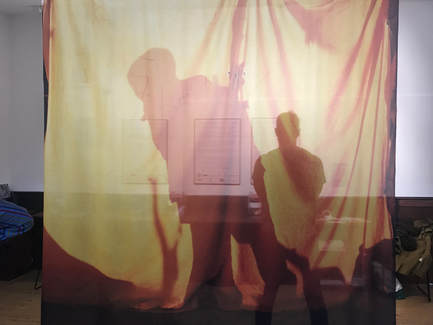

I also wanted to introduce the children to the entire process of photography, from pressing the shutter button to printing the photograph. So, I took them to the computer room, where we transferred and reviewed the photographs on the computer. Some children recognised their own photographs. Together, we chose the best ones, and the children even saw the printing process. Later, we created an exhibition of their photographs in the playroom, which they still enjoy looking at today.

Incorporating photography into kindergarten and home activities has many benefits for children. Children will learn new skills, have fun, and develop while doing so. Therefore, I would like to encourage parents and educators to take advantage of the opportunity and encourage children's creativity through learning photography in preschool.

https://www.tjasakovac.com

RSS Feed

RSS Feed