Teachers of arts subjects, like photography, can consequently feel embattled, belittled and marginalised. What place does a subject like photography have in this brave new world of what works? What role does knowledge and cognitive ability have in photography? What are the particular affordances of photography? How might it develop a student's character? What do photography teachers teach? Is photography 'hard' or 'soft'?

One of the ways we might want to theorise about teaching and learning in photography is by referring to various educational taxonomies. Our most recent addition to this website is a page devoted to Photo Literacy. It is a parallel development to our Threshold Concepts and related resources. Rather than viewing this as narrowly focused on language, we prefer to define Photo Literacy as follows:

a specific type of understanding that combines visual, linguistic, emotional and physical acuity.

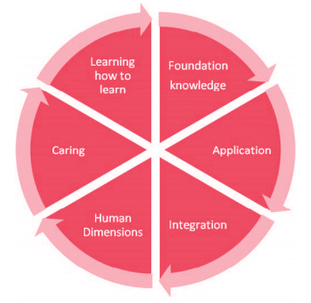

By exploring the various taxonomies of learning we outline ways in which photography teachers can remind themselves (and others) of what and how students are being taught in their lessons. By deliberate questioning in lessons we can draw attention to this vast range of skills and abilities, making the implicit explicit.

There are certainly limitations to these taxonomies. They tend to suggest that learning is hierarchical - that students can't be creative, for example, until they have 'mastered' knowledge and understanding. It's important to be too literal in the interpretation of them. We are all aware that learning is complex, interwoven, iterative and cyclical in nature. We should not expect photography students to progress through the stages of Bloom's Cognitive Domain in any kind of logical sequence. We should not delay opportunities for students to be creative until we have instructed them in the whole history of photography. Likewise, an over-emphasis on writing or memorisation of facts, will not lead to greater Photo Literacy. We must resist attempts to limit photography.

We must defend and celebrate the particular affordances of the visual, emphasise the importance of intuition, of feeling, of not knowing and unlearning. Students' breakthrough moments will be unpredictable. They may struggle with some aspects of the course (taking what seems like an inordinate amount of time to emerge from a particular threshold) but may take like ducks to water in other aspects of their programme of study. However, we hope that by outlining some of the ways in which educationalists have theorised about learning, by shining a light on taxonomies other than the cognitive, and by providing some ways in which teachers can use questioning and dialogue to draw out their students' learning, we can all better argue for our rightful place in the curriculum - right at the very heart!

-- Jon Nicholls, Thomas Tallis School

RSS Feed

RSS Feed