"While photographs may not lie, liars may photograph."

-- Lewis Hine (1909)

As any linguist will confirm, all well formed sentences contain a subject and a predicate. Language is thus a system of procedures by which we ascribe attributes to things through the use of arbitrary symbols. Only the most intelligent creatures can do this because only the most intelligent creatures are capable of following the rules necessary to engage in practices of predication: of the socially negotiated attribution of abstract linguistic tokens to objects and states of affairs.

It should be clear to everyone that images are not linguistic entities, yet quite evidently it is not in the least clear. Almost all theories of representation refer to images as "signs" or "signifiers", as "readable" objects or "messages" that require "decoding", "deciphering" or "interpreting." In everyday use, we talk of how images "convey meaning", "have content" and are "about" the things to which they "refer." We also talk of what images "tell" us, what they "describe", "articulate", "suggest", "explain" and "imply." And it is not impossible to find reference to images as oracles and chronicles or soothsayers or that they predict the future, commentate on the present and narrate the past. It might help to exemplify the absurdity of such thinking by noting that we can say the exactly same of tea leaves or the lines on one's hand. That we can do so, reveals far more about our infatuation with language than it does about the nature of images or the susceptibilities and skills that enable their use.

Any student wishing to understand the question of how images actually work (this was the title of my presentation at the conference by the way) will be met by an impenetrable thicket of confused and over complex theorisation about these profoundly simple but powerful tools. They will have to assimilate and understand numerous technical terms like "denotation", "connotation", "punctum", "studium", "icon", "index", "symbol", "sign", "referent", "veridicality", "verisimilitude" etc. And with each step along this path they will be no closer to the answer they seek. In fact, with each step, they will descend deeper into a convoluted labyrinth from which there is little hope of return.

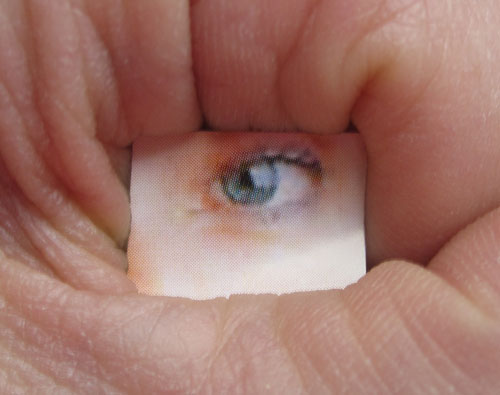

Depictive images work because they can be mistaken for the things they represent in certain ways and in certain respects. It is as simple as that. There are ways to make images resemble the things they depict because there are ways and respects in which they can be made more or less indiscriminable from them, ways that fully exploit the potential for illusion. You simply cannot do this with words — words do not look anything like the things they stand in for.

So when we say that images "tell" "truths" or "lies" we ignore their essential nature and instead treat them as linguistic items. In ordinary usage this is fine, but strictly speaking (which is what we should require of all serious theories) lying and telling truths are the exclusive preserve of language users. Of course, images can depict things that never did, could or will ever happen. But nonverbal misrepresentation does not reduce to verbal misrepresentation: to lying. Images are not texts and the skills necessary to use them for communicative purposes are by no means reliant upon (although they are massively assisted by) our skills as language users.

There are two fundamental questions we can ask of any image: "What is it of?" and "What is it about?" The first is always more basic than the second because the second relies to a very significant degree on the first. If it were not a matter of some importance what images are actually of, then we could indeed replace them with abstractions, with symbolic tokens, with words. We can do this of course, but not without significant loss.

Recognising what an image is of, is usually effortless, whereas the answer to the question of what an image is about — what it means — is almost never so. In fact the answer to the question of meaning is about as straightforward as the answer to the question of the function of a length of string. If you do not know how to use a length of string, then it has no function. The same is true of meaning.

Images can neither lie nor tell the truth. They can be used in acts of lying and they can be used to corroborate truths, but just as a nonverbal human witness can point to the perpetrator of a crime with no recourse to language, so too do images gain their fundamental efficacy from factors that are entirely independent of linguistic competence. Images can be deceptive but they cannot deceive. They can mislead and misguide but they cannot cheat. They can be clear but they cannot be honest. They can distort but they cannot feign. They can simulate but they cannot pretend.

Images are powerful because they trigger many of the same embodied responses as the things they represent — just as words do in fact. But, unlike language, they do not require elaborate skills in symbolic substitution and rule following to do this. So it is simply mistaken to suggest or conclude that images are bearers of truth, tellers of tales or descriptions of the world. If someone shows you a view through a window, they are not showing you a lie and nor are they showing you the truth. Likewise, a view of the moon through the distorting lens of a telescope is neither factive nor fictive. When we present evidence of the truth, the evidence does not constitute the truth. Truth is not something that can be perceived. When we say "I see the truth" we do not mean to suggest that the truth is something that can be seen. We mean that the truth is something that can be understood.

During the conference, another of the presenters mentioned something that struck me as relevant to this analysis. Apparently the root of the word "epiphany" is to be found in the Ancient Greek term: phanein, meaning "to show." Images show us things. It is what we do with images, and more specifically, the communicative practices within which images are integrated, that transforms them into such extraordinary and useful tools. Language enables us to use images in extraordinarily sophisticated ways, but language also significantly obscures our understanding of these essentially mute witnesses.

Jim Hamlyn

RSS Feed

RSS Feed