Note: Unless otherwise stated, all the quotations are from Gert Biesta's World Centred Education, Routledge 2022

Biesta offers a stark reminder about what's at stake here. In the race to the top of the league tables and ever greater competition between schools, students are at risk of being made the objects of various interventions:

We are too quickly drawn into monitoring and measuring the learning itself, looking for the interventions that will produce the desired learning outcomes, trying to control the whole machinery, and thus easily lose sight of the fact that children and young people are human beings who face the challenge of living their own life, and of trying to live it well.

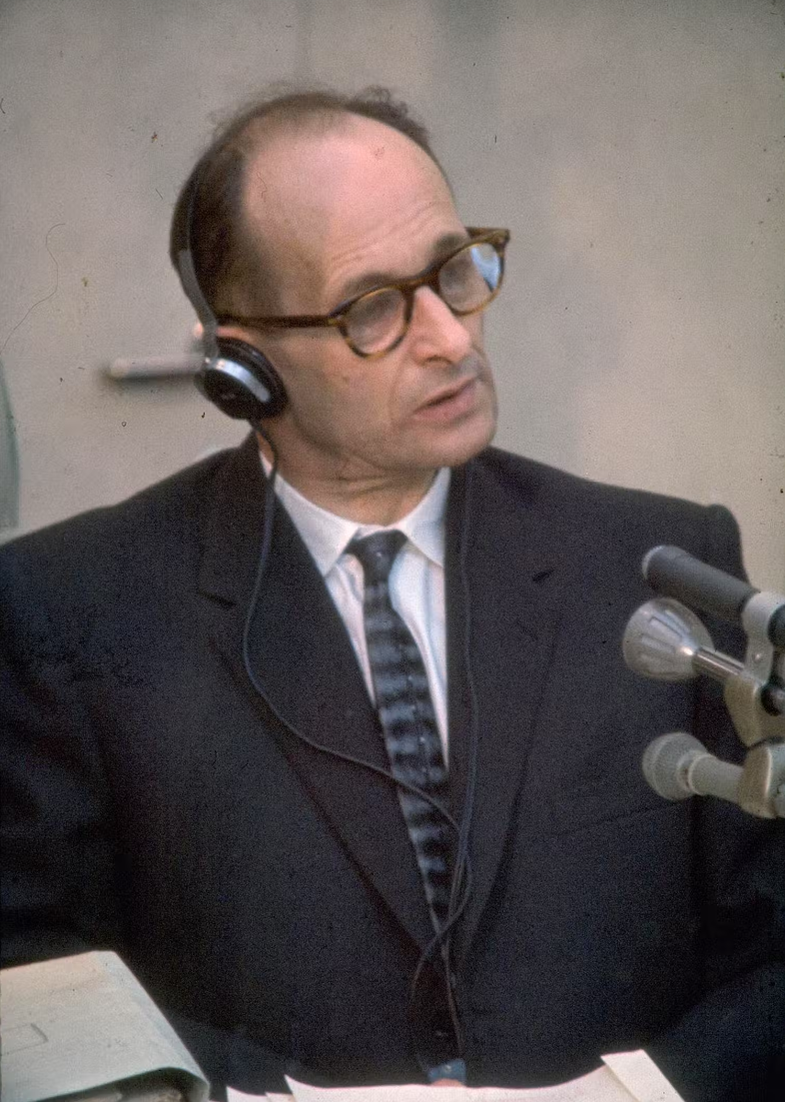

[...] we still live in the shadow of "Auschwitz" ... because it has shown us that the systematic objectification of (other) human beings is a real possibility with disastrous consequences.

Unlike populism, the very point of democracy is that you cannot always get what you want.

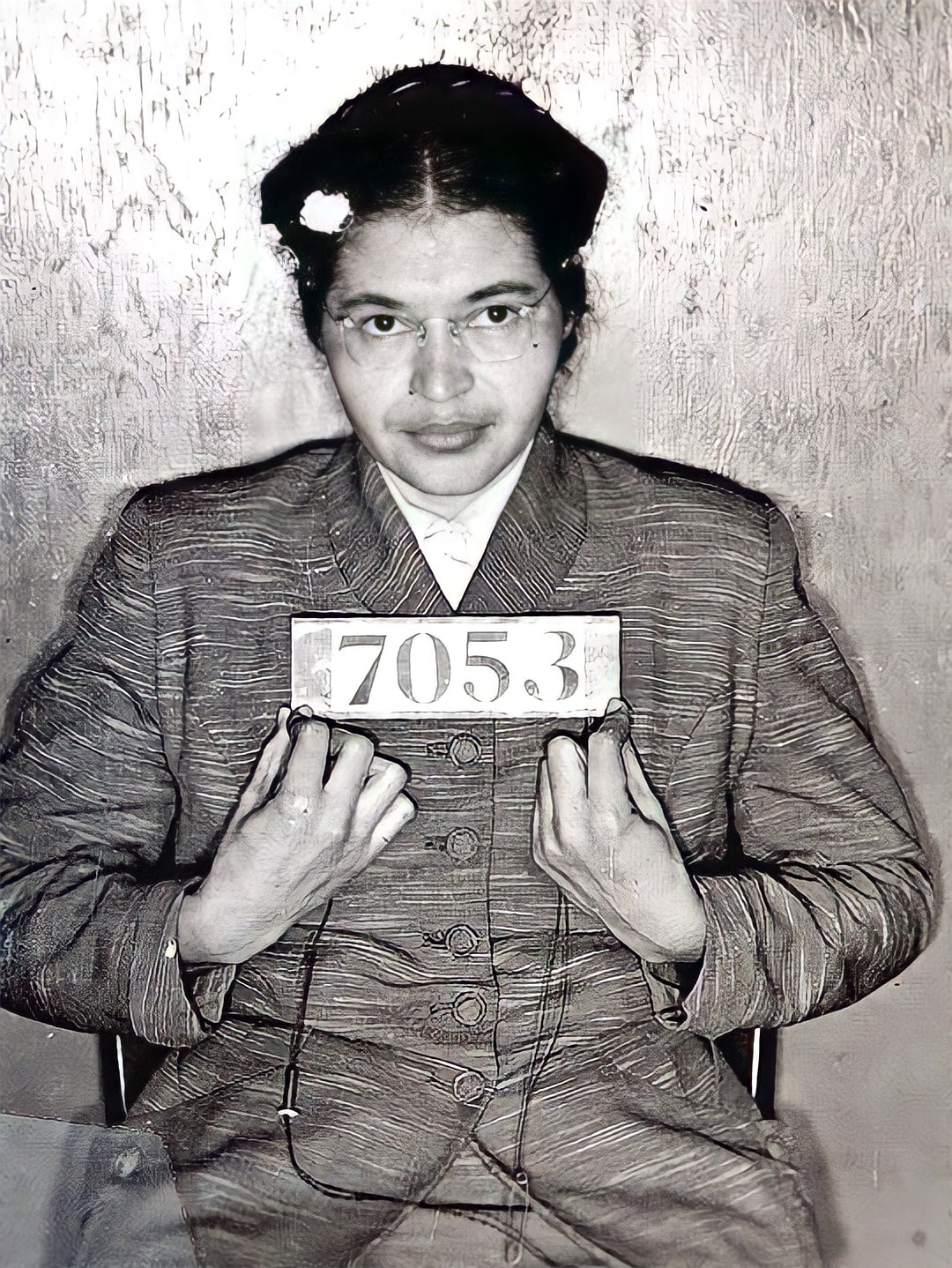

The Parks/Eichmann Paradox

Turning our attention to photography education, how might we open ourselves up to a more balanced view of the purposes of our lessons so that we can find more space for subjectification. Biesta, and others, provide us with several clues about how this might be achieved.

On framing

The difficult work of teaching, therefore, is not that of providing students with knowledge - which makes the current insistence that schools should focus on "knowledge" a bit silly - but is that of pulling students 'inside' the frame within which such knowledge begins to make sense [...] It is precisely this latter act of "pulling" that goes fundamentally beyond all the sense-making that students can do, up to the point where they encounter something new, something radically "beyond" their own horizon of understanding.

On not knowing

The eye should learn to listen before it looks.

-- Robert Frank

The sense of smell is invoked by photographer Peter Fraser to describe his (almost uncontrollable) receptivity to both external and internal stimuli:

It’s almost as if there’s a smell in the air and I’m being forewarned that a moment is approaching so I need to have the camera ready. In a sense, I never set out to do anything other than make myself available to allow that moment where there is an upsurge of energy from the unconscious mind into the conscious mind which is the moment when I know I have to make a photograph.

-- Peter Fraser

On resistance

The educational significance of the arts, and perhaps the educational urgency of the arts, lies in art education beyond expressivism and creativity [...] Art is the dialogue of human beings with the world, art is the exploration and transformation of our desires so that they can become a positive force for the ways in which we seek to exist in the world in grown-up ways. And that is where we may find the educative power of the arts

-- Gert Biesta, Art, Artists and Pedagogy, 2017

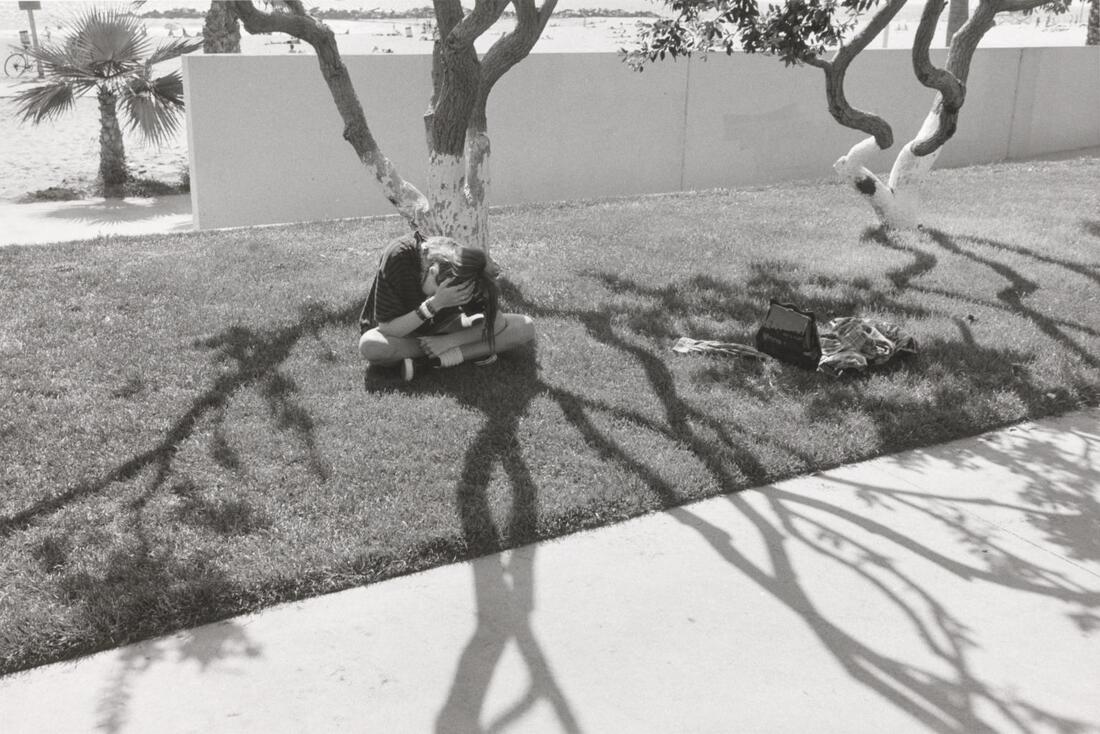

When you’re photographing and you’re walking through the world, something catches you, you notice something. You’re connecting with it and you’re responding to it. You’re basically saying “Yes” to it. You’re saying “Yes, it’s interesting.” You’re kind of like a free agent between your instinct, your anticipation and your intelligence and those things keep moving back and forth in a very fluid way while you’re photographing and that experience is really pleasurable. It’s really exciting and it’s the reason that I photograph. That and the way photographs look. The way they describe the world.

-- Henry Wessel

On pointing

On risk

The significance of pointing [...] is that it doesn't force the student into anything, but appeals to his or her freedom and, in a sense, reminds the student of his or her own freedom. Precisely because of this, precisely because the freedom of the student is at stake and, more specifically, because the freedom of the student is called upon, the work of teaching is without guarantees.

[...] without subjectification education runs the risk of becoming the "management of objects".

RSS Feed

RSS Feed